“I’m Very Much Into the Science of Building the Production Brick by Brick”: Caroline Jones Explains Why Production Elements Are Crucial to Songcraft

The country singer-songwriter reveals her secrets to studio success

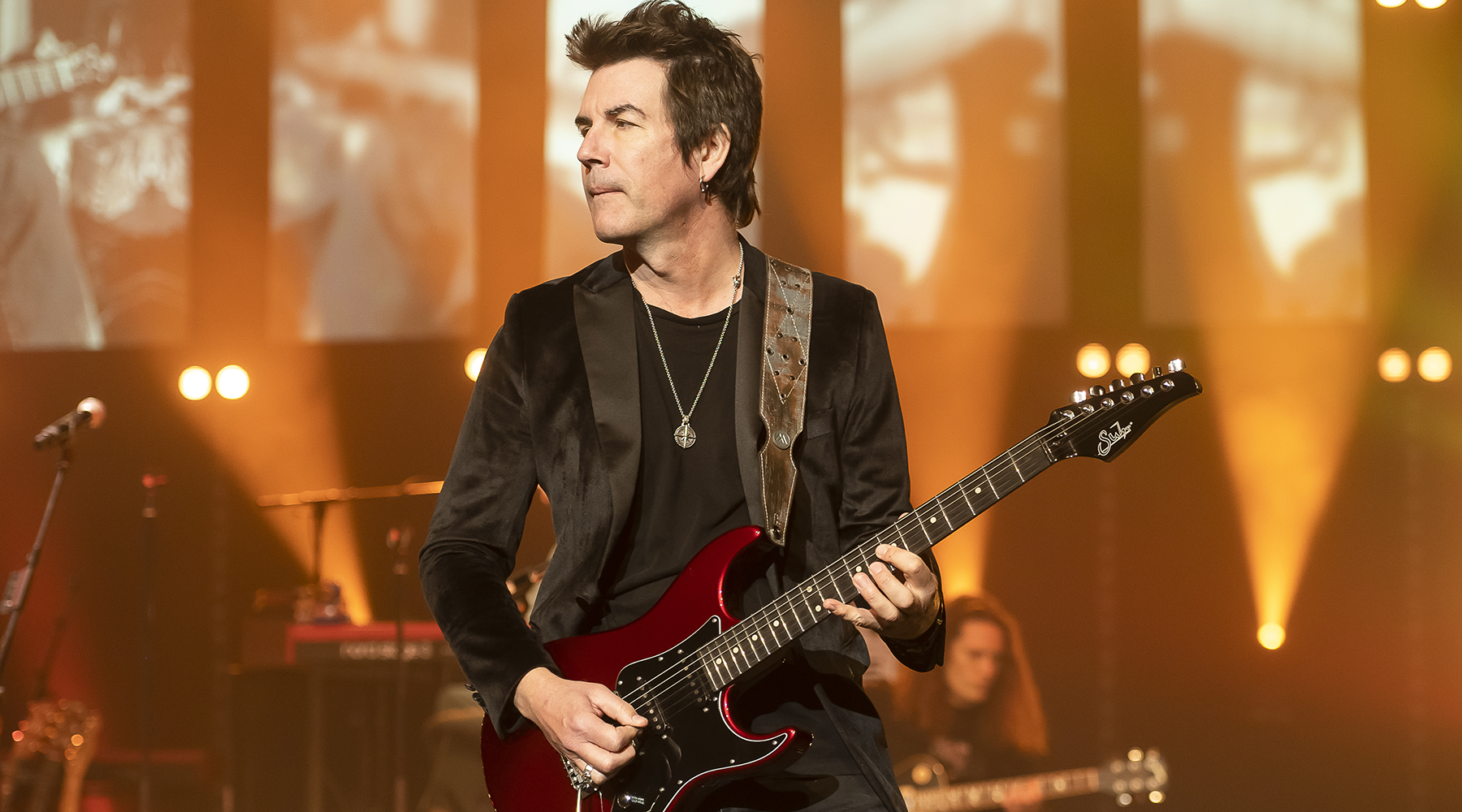

Multi-instrumentalist Caroline Jones – who plays everything on her records except bass and drums – released her debut album Bare Feet in 2017, showcasing her talents on acoustic and electric guitars, banjo, lap-steel, keyboards, and harmonica.

In 2021, the singer-songwriter’s follow-up, Antipodes, spawned the country hit “Come In (But Don’t Make Yourself Comfortable)” and debuted in the iTunes Country Chart top five.

Featuring collaborations with Joe Bonamassa and Mac McAnally, the album was co-produced by Jones alongside long-time studio ally Ric Wake (Mariah Carey, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston.)

She’s a “big production” nerd, and here she offers some excellent ideas for balancing multiple elements and textures without obscuring the main impact of a song.

As you play a lot of instruments, is it a challenge casting which ones will serve a particular song?

I typically write on piano or guitar, and those instruments provide the basic harmony.

Then, I start to hear the different sonic textures that can make a song greater than the sum of its parts.

I start to hear the different sonic textures that can make a song greater than the sum of its parts

Caroline Jones

I also have fun figuring out the rhythmic components, because a syncopated electric guitar or synth hook adds so much to the overall production. I love how all those elements work together, but, honestly, it’s a big process of trial and error.

Luckily, I have a very patient producer in Ric Wake, because we’ll often spend an entire day finding the right guitar sound or guitar part for a chorus.

So would you say that your songs are not really complete until you lock them down in the studio?

I’m very much into the science of building the production brick by brick, and I consider production elements as an extension of the songwriting process.

For example, “The Difference” is driven by my 5-string banjo riff, but what makes the song really exciting is the syncopated synth bass in the choruses, and that came to me in the studio.

Obviously, you want the lyrics and the melody to stand on their own, but if other parts create a dynamic structure that serves the emotional narrative, then those parts are essential to the song.

Are you concerned about commercial viability as you write a song?

That’s a huge rabbit hole, because it’s constantly changing, and, at best, you’re only going to be a good copy of everyone else who is chasing the same thing.

You can’t be distracted by other people’s voices, or ideas of what kind of music you should be making.

I just know that when I’ve written my best work, I want to hear the melody over and over again

Caroline Jones

You should have a team of people who are really onboard with your creative mission, and who will help you reach the highest expression of your personal artistry.

Currently, it’s popular to have many writers working on a song. What’s your view?

Whatever inspires the artist and the song-writer is fine – just as long as it’s not some guy in a suit saying, “I think this song needs a bridge written by this hot new writer.” I don’t think that kind of “manufacturing” serves the art or the artist.

But if songwriters feel inspired to get in big groups and write together – more power to them. I co-wrote in Nashville at the beginning of my career, and I learned a lot, but I felt more inspired writing by myself.

How do you determine whether a song is ready for prime time?

The whole process is still a big mystery to me. I just know that when I’ve written my best work, I want to hear the melody over and over again. I can’t stop singing it. That’s when I know I’ve got something.

Visit the Caroline Jones website for more information.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened