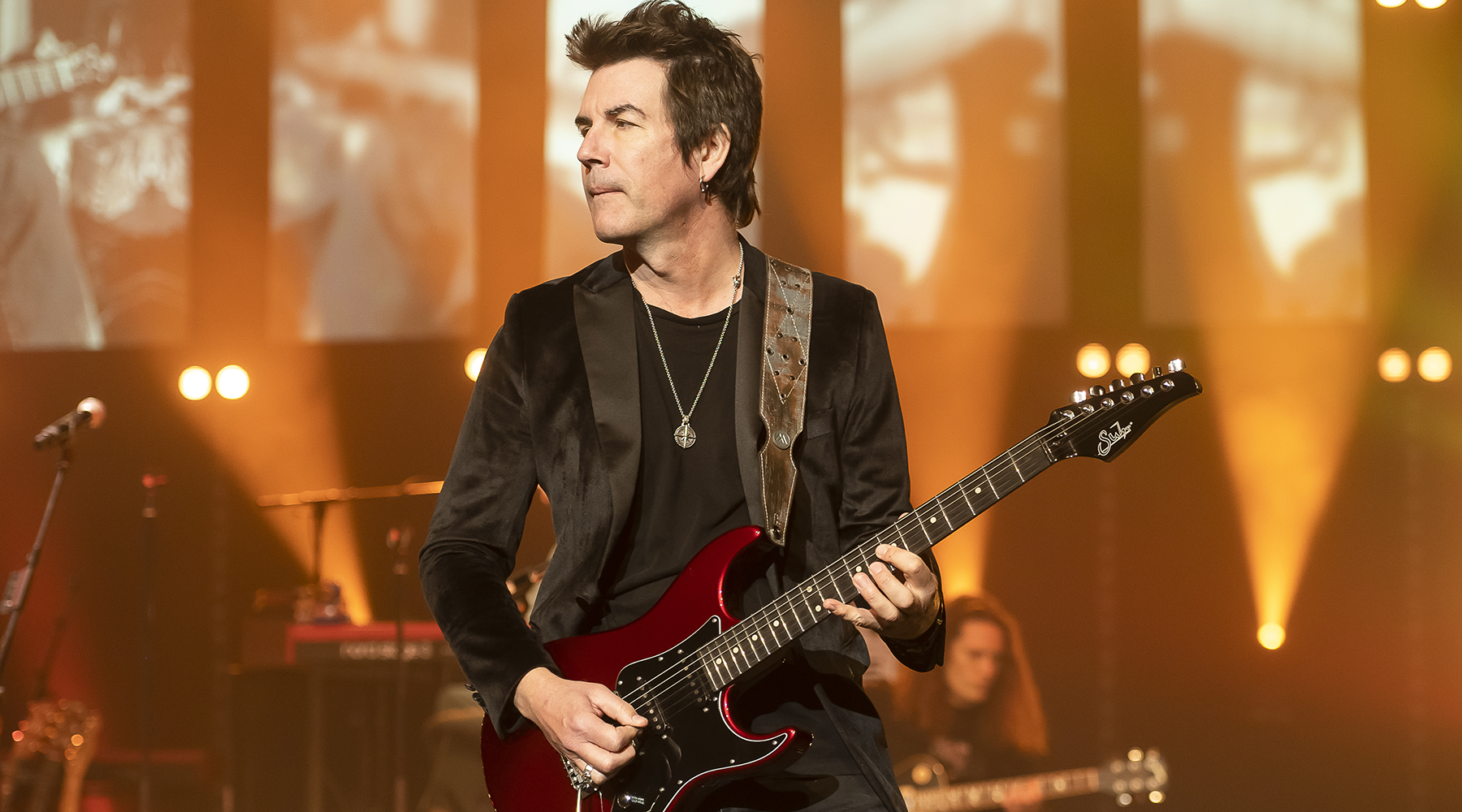

Carl Verheyen on the Mesmerizing Sounds and Memories That Make Up His Stellar New Album, 'Sundial'

How a chance duet with Art Garfunkel helped inspire the writing behind the Supertramp guitarist's bravura solo album.

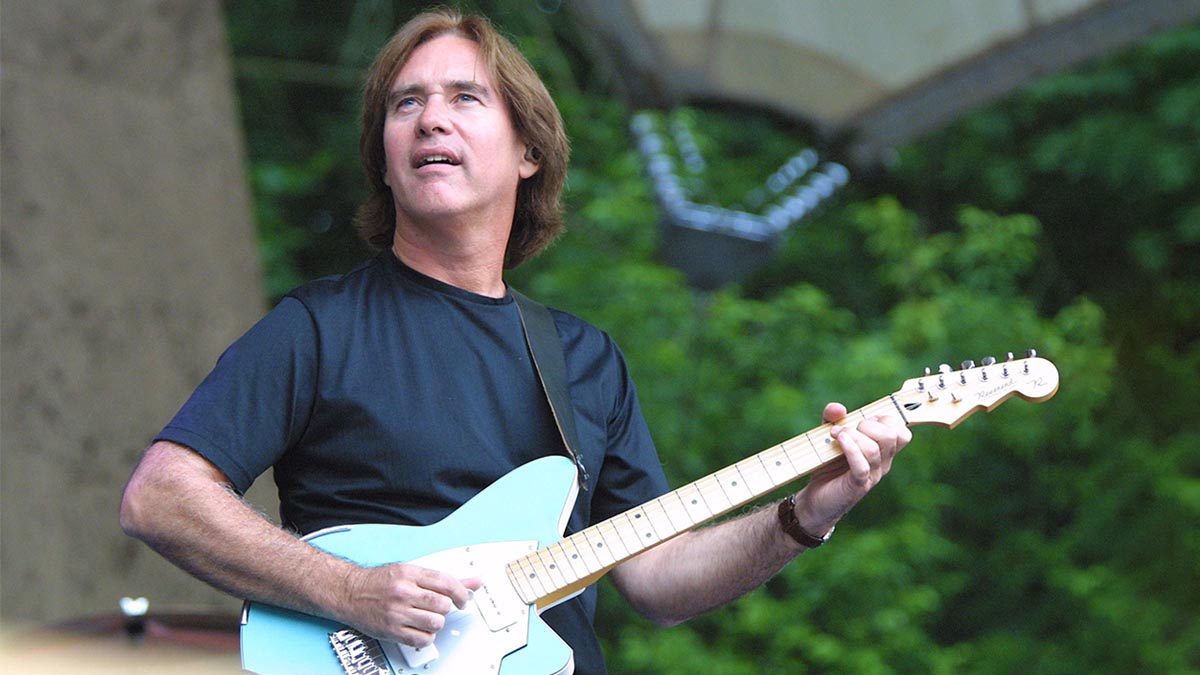

It’s not surprising that Carl Verheyen’s latest release, Sundial (Cranktone Entertainment), is an adventurous album loaded with world-class guitar playing. That’s a given for this super-picker, who has spent his life as a first-call session player, a solo artist, and a long-time member of the British group Supertramp.

On Sundial, Verheyen covers everything from rock and ska to funk, Afro-pop, and ballads, one of which, “Garfunkel (It Was All Too Real),” is based on a serendipitous event that took place when he was just 15.

I heard someone sing, ‘When you’re weary,’ and it was Art Garfunkel, standing over my shoulder

“I was at a hotel with my parents in Alberta, Canada, when I spotted a grand piano in the lobby and sat down and started playing the intro to ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water,’” Verheyen recalls.

“When I got to the big Eb chord, the downbeat to the verse, I heard someone sing, ‘When you’re weary,’ and it was Art Garfunkel, standing over my shoulder. I guess he was checking in at the front desk and came over just to blow this kid up.

“It sure blew my mind, because that was the number one song on the radio at the time, and here’s the guy singing it with me. So I wrote ‘Garfunkel’ for this album about that incredible experience. For the big guitar solo, I initially played the melody to ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water,’ using my ES-335 with this gorgeous soaring distortion sound.”

“The record was finished when it suddenly dawned on me that I might need to get permission. My music attorney said that he’d sued people for less, so I got in touch with Universal Music Publishing, and a week later they said permission was denied. So now the record is at the pressing plant, and they were going to start pressing it in an hour!

“That morning, I recut the solo in my little home studio, where I have a Neve 5211 mic pre and a Kemper Profiler for guitar overdubs. I actually think the song came out better without ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ in there. It might have gotten a little hokey feeling to me in a couple of years anyway.”

Verheyen called on another experience that inspired the high-flying track “Spiral Glide.” The story goes that when he joined Supertramp in 1985, he was tasked with performing something similar to the long solo David Gilmour played on the title track to the band's album, Brother Where You Bound.

Verheyen says he later met Gilmour backstage during Supertramp’s week-long engagement at the Royal Albert Hall and he wrote “Spiral Glide,” with its solo as a tribute to the guitarist, whom he calls a “lifelong inspiration.”

What did you learn from channeling Gilmour’s solo live with Supertramp?

One key element of his style is to wait for that beat to come around. He’s just so languid and in no hurry to play the melodies, and he’s got such nice touch and great feel and tone.

It’s different than when you’re channeling, say, Billy Gibbons and you think, Okay he’s got a Les Paul and Fender Champ type of amp, and he uses a lot of pinch harmonics, and you kind of get the ornamentation of his style onto your hands.

With Gilmour, it’s a different set of things. It’s a Stratocaster and a certain kind of vibrato and a certain tone, and it’s about milking everything you can out of a note.

What did you use on “Spiral Glide,” and what created the rotary effect?

For the solo, I played a Strat though one of my Dr. Z amps – I have a SRZ 65, a Z Lux, and a Karnen Ghia – turned up real loud. The rotary effect was an old Fender Vibratone cabinet plugged into a semi-distorted amp. I forget what it was, but I used a pedal in front of it and just got a real weird cranky sound.

“Sundial” is a tour de force of acoustic and electric textures. What was your approach on that one?

I think interesting guitar records are ones that use a lot of textures and sounds and different instruments. I tried all kinds of acoustics and settled on my 1959 Martin D-18 because I wrote the song on that guitar and it just spoke the best to me.

For the solo, I used my ’66 SG. I also wanted a jangly part and was going to use my Rickenbacker 12-string, but what sounded best was a Danelectro guitar on one side and a Taylor 12-string on the other side to create the jangle that I wanted.

I think interesting guitar records are ones that use a lot of textures and sounds and different instruments

How does your approach to mixing different instruments work for distorted guitar tones?

I remember doing this session for the Bee Gees [“With My Eyes Closed,” from Still Waters], and the producer said, “It’s just power chords, so bring a Les Paul and a Marshall.” But I’m really into the various degrees of distortion, and power chords are all over the place: There’s semi-crunch Pete Townshend, there’s Van Halen hard-rock, and there’s heavy metal.

So I said, “Let me bring a truck of guitars and a few amps.” And it ended up that the best thing for that track was a thinline Tele with a semi-crunch sound and a completely clean Rickenbacker guitar mixed in. The combination of those two guitars was the power chords, and it was a far cry from what the producer asked for.

Did you stick with the Martin for most of this record?

No. Years ago, I was teaching John Fogerty guitar lessons for an entire year, and he turned me on to Gibson acoustics for rock-and-roll strumming. He said the Gibson kind of self compresses, like you hear on the Beatles’ Rubber Soul.

Fogerty’s philosophy was that Martins are great for delicate stuff and fingerpicking and bluegrass, but if you want to dig in and rock, you should use a Gibson.

And, boy, was he right! So I’ll switch, even in the middle of a tune if I’m doing a fingerpicking part and the chorus is strummed. I’m the only one who knows that the Gibson digs in and does something the Martin doesn’t do. You’d be surprised what it does when you need a lift in part of the song.

Fogerty’s philosophy was that Martins are great for delicate stuff and fingerpicking and bluegrass, but if you want to dig in and rock, you should use a Gibson

On “Clawhammer Man,” your tone is brighter and snappier, and you get this cool funky jazz vibe. What guitar did you use?

I used an LSL T-style guitar called a Soledad. It’s got f-holes and a chamber behind the bridge with little openings to the f-hole areas that act a bit like a speaker acoustically, but when you plug it in, it’s got a really interesting character. It has a P-90 in the neck and a humbucker in the bridge, and I used the P-90 for that song.

What were you running it through?

That’s those little Vox AC4 amps for the most part. Years ago, I was working with Mercury Magnetics, which makes transformers. They said, “Vox is making these AC4 amps in China and they don’t sound very good, so we want to try an experiment.” They changed the two transformers in the AC4, and that really made it sound good.

I went a step further and replaced the 10-inch speaker with a Celestion Gold, and I have two of those amps. I used my ’61 Strat for the solo through a Vox AC30. The object is to have some ear candy in there, so that each time you listen to it you hear different things.

If you can’t play it onstage or in the studio, don’t practice it. It’s completely worthless

Your bending on the solo for “No Time for a Kiss” sounds very Jeff Beck-ish, like you’re using the whammy bar all the way though it.

I’ve got about 14 Strats, and they’re all set up so that when I pull up on the bar, I know where I’m going interval-wise. So the G string goes up a minor third, to a Bb, my B string goes up a whole step, to C#, and the E string goes up to F. So there’s all kinds of licks you can do just because you know what’s going to happen when you pull up.

I played the melody on an LSL Strat with a maple neck. I wrote that tune when I was 24, but I just had the instrumental part and it was kind of a Pat Metheny thing. Year later, I decided to put some lyrics to it, because that melody just stuck in my head.

You’re meticulous in all aspects of your playing and sound. How does improvisation factor into it?

Years and years ago, I read a story on Chick Corea in Contemporary Keyboard magazine where he said the best of us are only improvising 30 percent of the time; the other 70 percent is stringing together stuff we’ve got worked out.

And that one little sentence changed my life, because I’m listening to “Spain” and “500 Miles High” and all those tunes, and I’m thinking Chick Corea never repeats himself. When he sees an Am chord, he’s got thousands of musical ideas that he can string together. I thought I needed to do that too.

I needed to figure out a method for composing lines and getting them strung together in various keys and for various chords and keys of the moment.

I’m still writing things down in my lick book whenever I come up with something, like a new line for Bb7 or a new idea for A minor. Then I try to access it in my practicing. But I don’t play any exercises. I’m a guy who believes that if you can’t play it onstage or in the studio, don’t practice it. It’s completely worthless.

- Sundial is out now via Cranktone.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.

"When they left town, I went to the airport and got to meet Ritchie, and he thanked me for covering for him." Christopher Cross recalls filling in for a sick Ritchie Blackmore on Deep Purple's first-ever show in the U.S.

"It’s as if all of Jeff Beck’s genius is right here on one album. There’s a taste of everything.” Joe Perry riffs on Beck, the Yardbirds and "The 10 Records That Changed My Life"