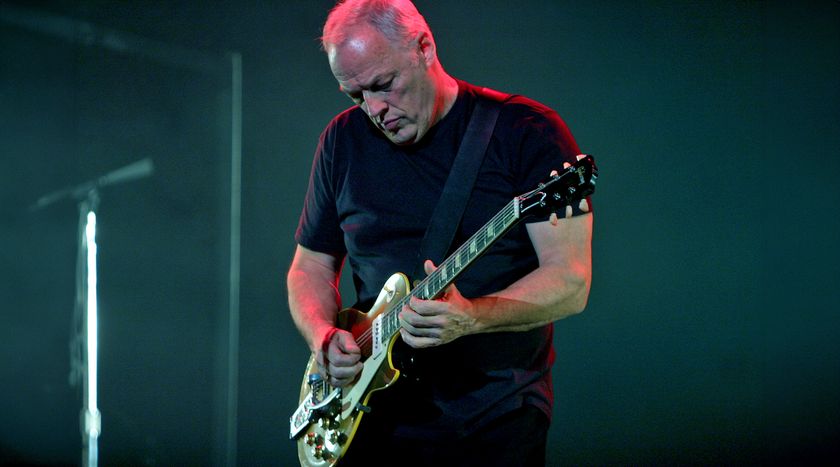

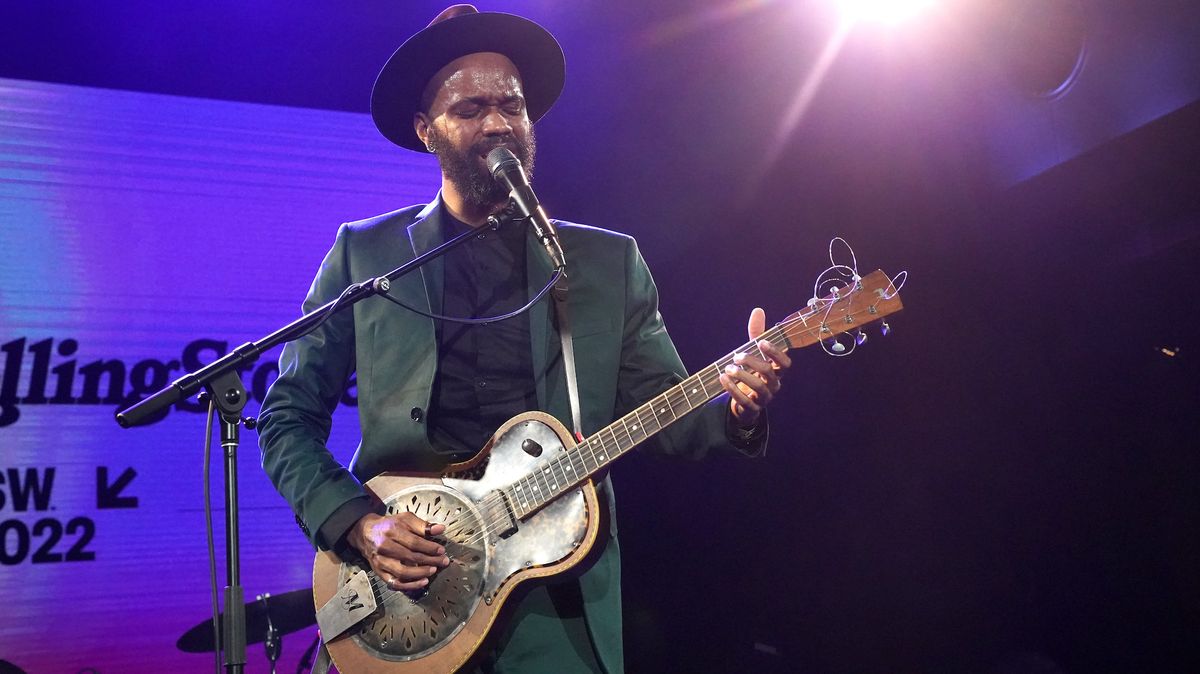

“When you show up to a set thinking you’re gonna hear acoustic blues and you hear tapping on an overdriven resonator, it might make you stop and listen”: Buffalo Nichols on breaking with blues tradition, and charting his own resonator-led path

With programmed drums, samples, some occasional two-hand tapping, and a renewed sense of purpose – as displayed on his sophomore album, The Fatalist – Nichols is taking the blues into the 21st century

Carl Nichols isn’t here to “save the blues,” whatever that means. Rather, on The Fatalist (Fat Possum), his second and latest album of blues-rooted music as Buffalo Nichols, he wanted to envision what the genre might sound like today if it “hadn’t been hijacked and trapped in amber,” he says.

Considering the evolution of traditionally Black music forms in the past half-century, especially the emergence and development of hip-hop, the logical next step in Nichols’ neo-traditionalist approach was to incorporate drum programming, samples, and synths into his resonator blues.

Songs like You’re Gonna Need Somebody on Your Bond make use of all of the above. Nichols performs the Blind Willie Johnson slide blues as ghostly samples of blues pioneer Charley Patton hover in the periphery, held in place by synth washes.

This isn’t a firm stylistic crossover, though; throughout The Fatalist, Nichols peppers his lyrically driven songs with slide licks, natural harmonics, and other tricks he’s learned playing rock, metal, bluegrass, and blues.

“I thought if I could bring all the old and the new together, it might help people understand the blues,” he says. “That’s what I was talking about with regard to the gentrification of the music. I wanted to just imagine what the music would sound like if it stayed relevant.”

After spending a spell in Austin, Texas, during which he recorded and toured behind his 2021 self-titled debut album, the Milwaukee native returned to his hometown to retrench and explore creative paths he had previously abandoned.

The Fatalist took shape around expanded instrumentation, such as fingerstyle guitar on The Difference and fiddle on The Long Journey Home. But listeners looking for extended soloing might be surprised by Nichols’ restraint, at least on his studio work.

“When I was a teenager, if I bought a blues album and it didn’t have three guitar solos per song, I’d be like, ‘Oh, this is no good,’” he says. “As I’ve gotten older, I just want to hear that less and less. I don’t ever want to be seen as a guitar player more than a songwriter, so I always try to save that for the live show.’”

We spoke with Nichols about the journey that led to The Fatalist, taking creative risks, and what he really thinks about the never-ending blues debate.

How far were you into The Fatalist when you returned to Milwaukee, where your career began?

“Probably half of it was written around the time of the first album. At that time, I didn’t have the creative control or the confidence to do what I really wanted. So I took some older songs and gave them a second chance. And then, as I started to see a theme in what I had been writing over the last couple of years, the rest of them came along.”

Did regaining creative control loosen things up for you?

“In the back of my mind, I still had this feeling like, I’ve gotta make sure this song is ‘commercially viable', because that was the term used by industry people that was burned in my mind. And I hate it. I’m still working on getting rid of those thoughts.

“But, in practice, I just did what I wanted. I took my own advice, and, for better or worse, I did things in a way that was my own idea. I didn’t really do much collaborating or ask opinions. I just wanted to see what was on my mind.”

Do you get pushback on your approach to the blues?

“A lot of people have this expectation that I’m gonna be a traditionalist, or somebody who’s gonna save the blues, or all these weird things people say.

“Certain things that are totally harmless in other genres – like promoting yourself in a confident way, or not wanting or seeking the approval of the people who are already at the top – is seen as this huge, offensive thing in the blues.

I am a blues artist, but not in the way that some people think

“I don’t care what these people think of me. That’s normal in punk and hip-hop and rock and roll. You’re supposed to reject a certain part of the past. I don’t go out of my way to offend people, but I’m not trying to do what they do, and people are offended by that.”

Do you consider yourself a blues artist?

“I’ve always gone back and forth on this question, because it means something different to me than to other people. I want to change the meaning of it for myself and just say, 'Yes, I am a blues artist', and let people catch up or figure out what that means, even though it makes my job a lot harder.

“But yeah, I am a blues artist, but not in the way that some people think.”

Your take on You’re Gonna Need Somebody on Your Bond is a clear departure from traditional blues arrangements. Why is it important to revisit canonical blues songs?

“Playing this kind of cultural music, I feel like I have a duty to at least give people a trail of breadcrumbs back to the source. If people can make that connection, they might go back and appreciate the old stuff in a different way. And then, at the same time, I wanted to imagine what blues music would sound like if it stayed relevant.

“That was the challenge, and the biggest goal I had was imagining a totally alternate universe where the music was cool and it didn’t get turned into cruise-ship music.”

When you show up to a set thinking you’re gonna hear acoustic blues and you hear tapping on an overdriven resonator, it might make you stop talking for a second and listen

You’ve been opening your cover of Skip James’ Sick Bed Blues with two-hand tapping. Is that your way of welcoming listeners into your world, to let them know you’re not just a guy who plays blues?

“Yeah, that is my way of trying to draw people in. I never want to offend my audience, but sometimes I like to see how far out there I can go, ’cause I know eventually I’m gonna come around and do that thing they want, and they’re gonna forgive everything I’ve done before that. That gives me a little bit more freedom.

“But the main reason was because the years of playing in bars and opening for people taught me all these little tricks to get someone’s attention for 10 seconds. When you show up to a set thinking you’re gonna hear acoustic blues and you hear tapping on an overdriven resonator, it might make you stop talking for a second and listen.”

What has being on the road so much revealed to you about your playing?

“My debut album was such a small part of who I was. As soon as it was out, I was like, 'Now I have to spend the next 10 years of my life trying to get people to understand who I actually am, and it’s not just this'.

“Right off the bat, I was experimenting live. In the past two or three years I’ve been so busy and haven’t practiced or explored music in a way that I used to. I’m relying on so much muscle memory and trying to remember these techniques that I practiced 10 years ago.

“Also, it’s forced me to try new things on the fly, and every once in a while it works out. It has made me be a lot more aware of my playing in the moment.”

Your flatpicking stands out on songs like Turn Another Stone. When did that style enter your lexicon, and how did it make it onto this record?

“A couple of years ago, some friends of mine played this Tuesday night bluegrass gig at a bar in Milwaukee, and I’d just go to hang out. Then the guitar player moved, and they were like, 'You want to play guitar in this bluegrass band?'

“I had never played bluegrass, and the only thing I knew about bluegrass was this one compilation CD that I bought from Target in, like, 2007. It had all these gospel bluegrass songs from the ’40s and ’50s on it, and that was all I really knew.

“I got into it for that bar band and started taking it more seriously, and then I moved on to something else. I have some other songs I play live every once in a while that are bluegrass inspired.”

A down-tuned, amplified resonator brings a lot of bombast. What is the aesthetic that you’re going for, sonically?

“I’m just trying to figure out what works. The way I play a lot of my songs relies on the bass with the thumb and the melody on the high strings. So one thing I was looking for was having really high tension on those high strings, and I had to go all the way up to the resonator gauge to get that.

“It also brings a totally different sound out of the pickups. So I just keep following the sound and seeing what sounds good and what doesn’t, and try not to break my guitars in the process.”

Buffalo Nichols’ new album, The Fatalist, is available to buy and stream now

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

"Shredding is like talking a foreign language at 10 times the speed of sound. You can't remember anything." Don Felder reveals the unlikely influence behind his iconic guitar solo for the Eagles' “One of These Nights”

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first