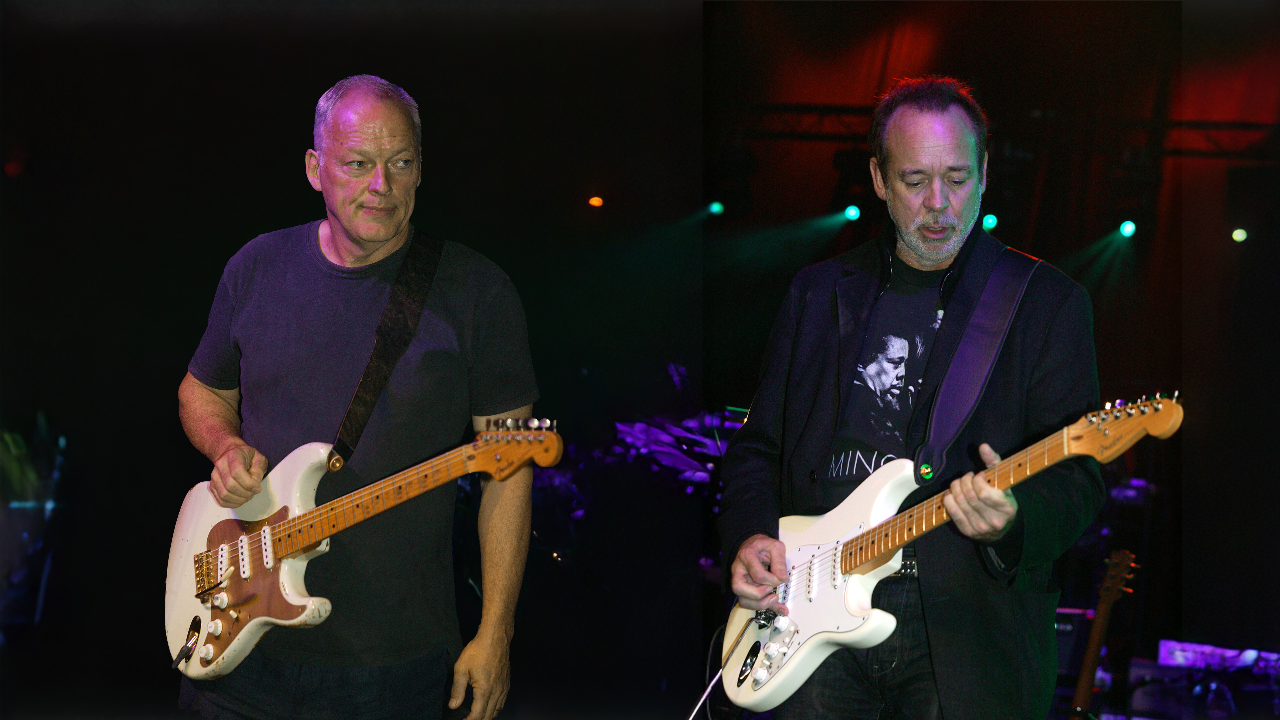

“It Was a Horrible Little Setup Upstairs, in the Corner of Our Bedroom”: How Americana Icons Buddy and Julie Miller Crafted Their ’Breakdown on 20th Avenue South’ Album Using a Laptop

The LP’s pristine sounds reveal how they were able to transcend the limits of a home recording setup

The following appeared in the September 2019 issue of Guitar Player

Buddy Miller developed a singular guitar style that would make him an icon in the music genre known as Americana. With a rootsy resonance grounded in country, blues and rock, and a healthy dose of Daniel Lanois-influenced ambience, Miller’s approach is one where prodigious technique is always subservient to soul.

Through seven solo records, as well as albums with Jim Lauderdale, Bill Frisell and others, Miller has honed a unique approach to twang, while his textural side was brought to bear in his work with Robert Plant’s Band of Joy. All of the above is applied to 2019's Breakdown on 20th Avenue South (New West), his third collaboration with his wife, Julie.

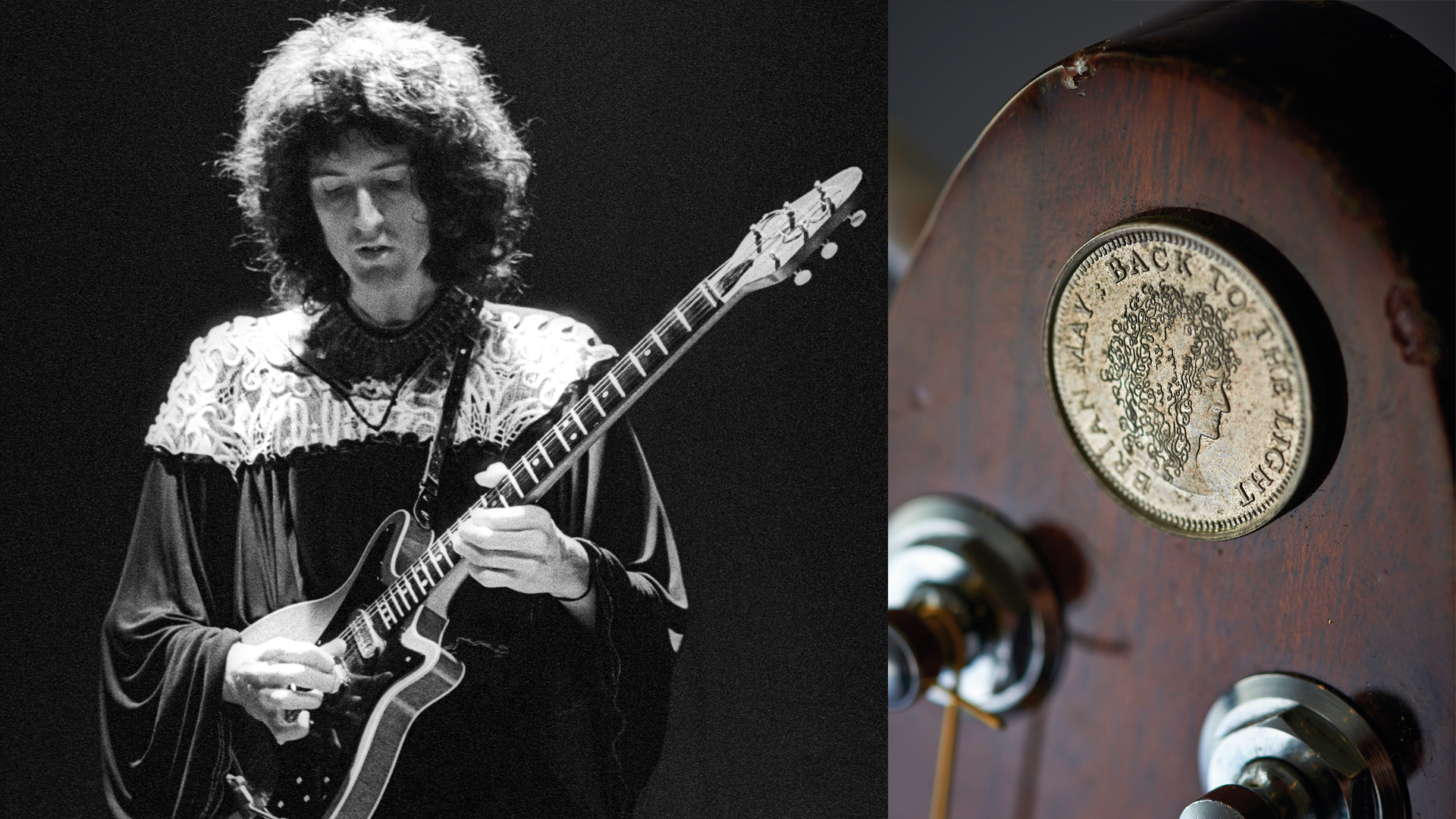

On some of the electric numbers, the tone of his trademark Italian Wandrè guitar is in evidence. Miller owns two of these radically designed instruments and makes no bones about their importance to his music. “I originally paid 50 bucks each for them, and they are the key to my whole life,” he says. “One is tuned standard, and the other one is usually either tuned up to F or down to Eb, because I like having the open strings.”

Miller initially thought the guitars were branded Noble because of a name that appears the back of the headstock. “Noble was an importer of Italian accordions in Chicago,” he explains. “I guess the Wandrè guitars came as part of the deal.” Indeed, with their glittery finish and push-button switching, a visual and mechanical resemblance to an accordion is apparent.

The glossy appearance is deceptive, however, as these are cheaply constructed guitars. “I’ve probably put 50 dollars worth of superglue into this thing over the years,” Miller says. “The fancy binding tends to come off. I only bought one because of the sparkles and then realized it sounded great, even acoustically. They are all I have played as my main guitar since I got the first one in the mid ’70s.”

These instruments come with a permanent cover over the saddles, creating a small issue. “You cannot palm mute easily,” Miller says. “I got okay at it, but unlike on a Fender or Gibson, you can’t put your palm where the strings meet the bridge.”

In another odd turn, the strings are pulled through holes in the bridge. In the early days, when Miller would be playing in clubs for six hours a night, it was not unusual for him to break a string on the Wandrè. “I got really good at changing it in the middle of a song, but it’s like threading a needle,” he explains.

The peculiar construction of the Italian guitar doesn’t end there. The three pickups are not attached to the body but instead float, supported by an aluminum strut to which the body is bolted as well. This doesn’t seem to adversely affect the tone. “You can get a good country sound with just the bridge pickup,” Miller explains. “When you put on two of the pickups, it’s kind of like a Strat sound.” Two of the pickups are physically out of the phase, as on a Stratocaster, while the third is electronically out of phase, producing the thin, funky tone associated with early B.B. King or Peter Green.

Two decades in Nashville may have given Miller the demeanor of a southern gentleman, but he grew up in the North, coming to country music through a circuitous route. The guitarist was born in Ohio, where he simultaneously saw Elvis and a six-string guitar at the age of three. Miller’s family soon moved to New Jersey. “My parents got me my first guitar when I was seven or eight – a $29 nylon-string,” he recalls. “This was pre-Beatles. The only book or instruction around back then was The Folk Singer’s Guitar Guide, by Pete Seeger, but we were halfway between Philadelphia and New York, so there was great radio.”

That’s where Miller first heard country music. “What got me hooked was the guitar playing,” he says. “James Burton and cats like that drew me in with their great signature parts.” Working with various bands later led him to Austin, San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York City, which, believe it or not, was a hotbed of country music for a while.

Following three solo records on Hightone, Miller recorded his first album with Julie, with the second following in 2009. Years passed before this third collaboration as the in-demand musician was sidetracked, producing or co-producing Richard Thompson, Shawn Colvin, Ralph Stanley, Jim Lauderdale and Robert Plant, as well as working and occasionally appearing on the television show Nashville.

The couple reignited their musical partnership recently when Julie began a streak of writing songs that begged to be recorded. Breakdown on 20th Avenue South takes its name from the location of the Millers’ house in Nashville. The home features a full-on recording studio that takes up most of the downstairs, but Julie, whose health has been erratic, declined to use it. “We didn’t record down here,” Miller explains. “It was a horrible little setup upstairs, in the corner of our bedroom. I couldn’t move in the chair, and the dog would get up on my lap. There’s one song where you can hear a dog bark every now and then.”

The “horrible” recording setup included a laptop and a Universal Audio Apollo X16. “The UA stuff is great,” Miller admits. “The Apollo has a feature called Unison pre-amp that allows you to use their Neve or Telefunken Preamp plug-ins while you’re tracking. It records the sound of their mic-pre modeling, which all of my engineer friends tell me is outrageously accurate. I’ve got real Telefunken V76s and Neves, but I didn’t bring them upstairs.”

Miller did take along a floor tom with a towel on it to lay down a loop, as well as a Wandrè guitar and one Swart amp. “I built up the tracks one at a time,” he explains. “I don’t usually make records that way. I’m used to having a guy on the drums that I can look at and play to.”

Working in such a small space, the guitarist found he needed to use another Universal Audio product, the Ox, for its attenuator feature. “It is basically like a power soak with a line out,” he explains. “I don’t normally use the modeling, although I might have used the speaker simulation on a couple of songs because it lets you turn the amp speaker off. It sounded amazing.”

After the luxury of recording on full consoles in commercial studios and his own, Miller had to adjust to mixing in the box with a personal computer. “I was working in a space that is four by four with a laptop and two little monitors,” he says. “I’ve edited audio in Pro Tools on a plane, but I don’t usually work that way. It wasn’t until after the record was finished that I realized you could plug in a mouse and a keyboard to make it feel like a real system.”

For their first joint effort in a decade, Miller let his wife take the lead and assisted by presenting her with a special instrument. “I got Julie this funny-looking acoustic Avante guitar,” he says. “She always likes me to play something like a guitar tuned an octave higher, which is the reason I have the electric Vox Mando-Guitar. The Avante is tuned D to D [above normal tuning], almost an octave up.

"It’s a great sound. She would write the songs on it, and that would become the sound of that song. I bought a second one because it’s a specialty sound and looks a little weird, so who knows how long they’ll make them.”

After the luxury of recording on full consoles in commercial studios and his own, Miller had to adjust to mixing in the box with a personal computer

Designed by Veillette Gryphon and distributed by ESP, the Avante is but one of a variety of cool instruments used in the making of Breakdown on 20th Avenue South. “I also have this Stella or Kay fixed up by Scott Baxendale in Athens, Georgia,” Miller continues. “He takes the top off these old Kays and Harmonys, rebraces them, and makes them sound great when they should sound horrible. This one is in a drone tuning.”

The title tune finds Miller forsaking his Wandrè for a moment. “I usually don’t stress over which guitar to play; I’ll just pick up whatever’s nearby and if it feels right, I’ll go with it,” he says. “I think that was a Gibson 330 with P-90s. I can’t usually get music out of Gibsons. I’m really not that that versatile of a player.”

Listen to the track “Unused Heart,” and you will hear Miller hitting a low C# courtesy of an old Jerry Jones baritone. “I’ve been using that a lot for the last eight to 10 years,” he says. “When I was playing with just me and Emmylou Harris, I would play baritone because it let me add some color and melody while playing bass at the same time. I also used it with Patty Griffin and Shawn Colvin. The scale’s different from a guitar. You have to stretch your fingers a little bit more, but it’s worth it, soundwise.”

Live, Miller favors a pair of Swart AST Pro amps, but the small space permitted the use of only one when recording with Julie. “I used the tremolo on the Swart for the record, but I use the Fulltone Supa-Trem live,” he says. “I love the Swart’s reverb. The springs react a little differently.”

On the solo for “I’m Going to Make You Love Me,” Miller sounds as if he is slamming away on the low strings of some mysterious instrument, creating an evocative sound that is hard to place. “Isn’t that the coolest thing? That’s just a guitar. It might have been the Wandrè or a Tele,” he says.

“I’ll tell you what was in the back of my mind. My secret weapon is an old Willy Joe Duncan record. He played a one-string Unitar, and it is one of my favorite recordings. I wasn’t consciously ripping that off, but months after we cut it I realized I’m doing Willy Joe Duncan. I was trying to do it on the A string, but it sounded better on the E string. That’s all that is. I’m just trying to impress my wife.”

“Underneath the Sky” offers up electric guitar tones that go from bass-saturated breakup to cutting treble, all a product of Miller merely switching pickups. “That’s an old track,” he says. “We started a Julie record 15 years ago. I did my record Universal United House of Prayer instead of finishing hers because she takes a long time and I’m used to making a record in a week. ‘Underneath the Sky’ meant a lot to her because her brother had just passed away. He was struck by lightning. That was cut with just me playing the guitar live and Brady Blade on drums. It’s only one guitar on that track.”

Though there are plenty of gritty electric workouts on the record, it is the pristine sounds of the acoustic instruments that reveal how completely the producer was able to transcend the limits of his recording setup. Of course, having great gear helps. “The main acoustic on the record is a 1934 Gibson L-00,” he reveals. “You can hear every string. It’s not like strumming a guitar, more like playing a piano.” Miller purchased the instrument from Nashville guitar repair guru Joe Glaser. “There was brace loose in it and he said, ‘I think it adds to the sound, so I’m just going to leave it that way.’”

No matter how good the guitar, when it comes to superior acoustic tone, miking is crucial. Miller has many classic mics: a vintage Neumann 254 tube mic, an old Shure SM5 and Telefunken U47s, among others, but he chose to use newer ones. “I didn’t want to bring expensive stuff upstairs because of the dogs, and because things fall over,” he explains. “That said, I used great mics made in Nashville by a company called Miktek. I used their small-diaphragm microphone on the acoustic. I think they only make one [the C5], and I love it.

“Most small-diaphragm mics, even expensive ones from high-end companies, have a bump at around 4-to-7k, which I find unattractive and unnatural. The Miktek mics are really flat and sound like the guitar. As to mic placement, I didn’t have many choices. I was playing at a desk in front of a laptop.”

Anyone who has seen Buddy and Julie Miller perform knows that they are one of the all-time great musical marriages, up there with George Jones and Tammy Wynette, and Richard and Linda Thompson. Unlike the others, the Millers are still an ongoing couple, but Julie’s health has precluded them from performing together live for many years.

We couldn’t let Miller go without asking him about his Band of Joy days working with Led Zeppelin legend Robert Plant. “That relationship with Robert came about in such a cool way,” he explains. “He was at an Emmylou Harris gig in London. I heard he was in the pub afterward, and went to meet him. We hit it off talking about Arthur Lee and Moby Grape. He loves country music and rockabilly, but our point of intersection was both being fans of West Coast ’60s rock. I guess I didn’t suck that night, because he kept my number and called when the Alison Krauss/Robert Plant tour happened [in 2008].”

Miller tries to take something away from every gig and every session, and working with this rock icon was no exception. “Robert is such a great band leader,” he says. “I learned so much from watching the way he communicates onstage. You have to spot the slightest shoulder gesture, because he’ll go out on a limb. It’s not the same set and certainly not the same vocal every night. There were certain songs where we could go wherever we wanted, and he would push the musicians to go there. His instincts are impeccable, so you just go with it.

“Nothing is set in stone and the arrangements are just guides. At certain times during the show, it’s going to seem as if we’re lost, because we are. I like that, so don’t tell me where the ‘one’ is. Don’t try to bring me back.”

Listen to Buddy & Julie Miller’s Lockdown Songs here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band