“I Kind of Stole Ed...And That Wasn’t Something That Happened Very Often”: Brian May Expounds on Eddie Van Halen’s Role in the Fabled ‘Star Fleet Project’

As he releases his expanded ‘Star Fleet Project’ box set, the guitarist reveals his thoughts on EVH, the future of Queen, and the dangers AI poses for music in the coming year

Talking to a rock star usually isn’t rocket science. Unless you’re talking to Brian May – er, that would be Dr. Brian May to you.

The Queen guitarist – who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II – is a bona fide PhD astrophysicist. He was studying at London’s Imperial College as his group was forming and launching in the early 1970s, then returned to his education in the mid ’00s, receiving the advanced degree in May 2008. Since then, he’s been as active in the scientific realm as he is in music. “I do stereo-photography for various unmanned missions to the objects in the solar system,” he tells GP via Zoom from his home in England. “So I’m hooked into various NASA and ESA [European Space Agency] missions, which is great.”

He pauses and offers a slight smile. “I can’t believe I’m saying this, ’cause it was a dream when I was a kid that I would work with people who are real astrophysicists and space explorers. But now I get to do it, which is wonderful. It takes up a lot of time, a lot of energy, but I wouldn’t lose it. I wouldn’t walk away from it for the world.”

May, at 76, is actually a case study in being able to have it all – including, of course, the music. Since the death of singer Freddie Mercury in 1991, he and Queen drummer Roger Taylor have kept the group’s legacy alive in other permutations – with Paul Rodgers, from 2004 to 2009, and, since 2011, with American Idol runner-up Adam Lambert, who has demonstrated an astounding ability to channel Mercury’s flamboyance and vocal chops onstage. As a result, Queen remain a going concern, even 15 years since their last new music, 2008’s The Cosmos Rocks, with Rodgers.

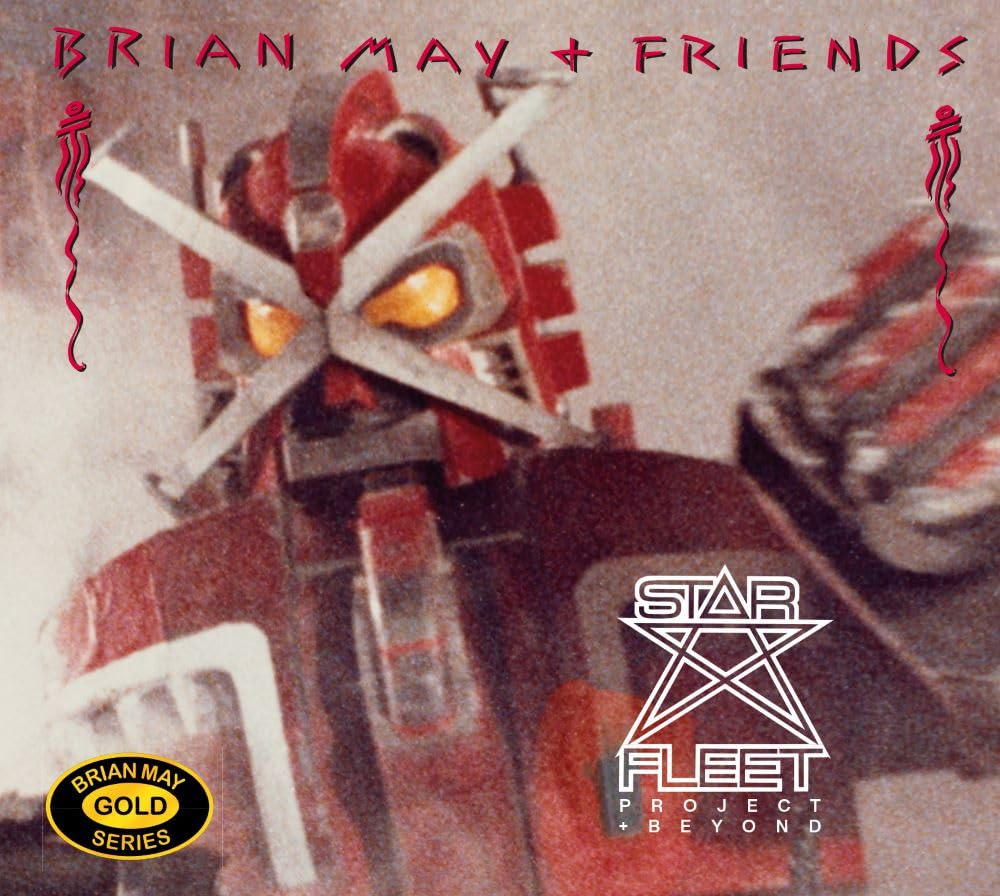

Queen and Lambert are back on the road this year, but May is celebrating another part of his past as well. Forty years ago, during a band hiatus, he stepped outside of the Queen confines for Star Fleet Project, a three-song EP recorded over two days – April 21 and 22, 1983 – at the Record Plant in Los Angeles by a troupe dubbed Brian May + Friends.

And what friends they were. First and foremost was Eddie Van Halen, riding high on the multi-Platinum success of his band’s first five albums. REO Speedwagon drummer Alan Gratzer, latter-day Doors bassist Phil Chen and keyboardist Fred Mandel (Alice Cooper, Pink Floyd, Elton John and Queen) rounded out the core band, while Queen bandmate Roger Taylor contributed backing vocals.

The sessions yielded three songs: the sci-fi flavored title track, which was inspired by the Japanese TV series X-Bomber (released as Star Fleet in the U.K.), which May’s then-young son Jimmy favored; the bluesy, Queen-styled rocker “Let Me Out”; and “Blues Breaker,” a nearly 13-minute band-composed opus dedicated to Eric Clapton. Star Fleet Project came out on Halloween of that year and was May’s first foray outside of Queen, which would be followed by two solo albums during the 1990s (Back to the Light and Another World) as well as the 2000 soundtrack to Furia.

For the album’s 40th anniversary May has put together a box set, remixing the three tracks and adding alternate takes and jams from the sessions. For aficionados, The Complete Sessions disc offers a lot of May and Van Halen playing, and a deep look at how the august ensemble worked together and brought the songs into shape.

Grinning widely, May talked to GP about this trip down memory lane.

What does Star Fleet Project mean to you 40 years on?

It’s a very important part of what I am, and it’s something I really wanted to be buttoned-up and safe and out there for all time. It’s a precious moment that I felt was getting lost on some shelf, and I wanted it to be out there so that people could experience it the way I experienced it. Luckily the analog tapes are still there. Hearing that stuff is not just nostalgic – it’s inspiring, and very emotional. So it means a lot to get it out there, just so it will always be there.

How did the whole project come to be?

Back then, I was absolutely engrossed in Queen. For years we went into the studio for three months, and then we went on tour for nine months. It was completely all-encompassing, and this was a point where we took a break, ’cause we really needed to get away from each other for a while. Suddenly, I had the opportunity to open a different door. And it was an adventure, ’cause I had no idea what would happen. I’d put all these people in the studio together with me, and maybe nothing would happen. And then I went in to do it, and it was the experience of a lifetime.

It was the experience of a lifetime

Brian May

Did it take long before you realized that it would work?

The first day was so full of adrenalin and a good kind of nerves, and just the joy of discovery – the discovery of each other and creating in a different arena, a different universe almost. We all go in there and suddenly it’s happening, and the tape is rolling. And it’s kind of a bluff, ’cause we don’t really know what we’re doing, and gradually we do it a few times and it comes together. We eventually sound like a band, which is a miracle, really, because I don’t think I ever expected it to gel quite that well.

It’s the outtakes that are the most valuable for the listener. You really get a chance to hear the five of you evolve and learn to play together, in a very short time, too.

It’s nice that you say that. We’d never played together before. There was no rehearsal period. What you hear in the Sessions part of this box set is exactly what happened the first time we ever got together and switched on the amps and tape machines. Every single take, every mistake, every laugh, a lot of funny stuff. You can hear that chemistry evolving.

We did have a little bit of preparation, because I had a couple of demos which we circulated to the guys. I didn’t want to go in there completely unprepared, so I sent a little demo of the title track to each of them – a little cassette with me singing and playing acoustic guitar, demonstrating the chord sequence and the development of this song. And there was also a very rough version of “Let Me Out.” So they all knew kind of what was in my head, and Ed popped around to my house in L.A.

Just like that?

[laughs] I’d recently got a house there, ’cause we were effectively being Californians for a short period. My little boy went to nursery school there. So Ed came around, we plugged our guitars into a Rockman and played to each other and experimented a little bit. I wouldn’t call it “rehearsing,” but we had some fun, and I showed him what was in my mind. Phil Chen came around and we did the same thing with the bass. And Alan was my neighbor. We saw quite a bit of each other, so we had a chance to talk about it, but we never, until [Star Fleet Project] played with each other. So Alan was a good friend by that time. Fred Mandell is a virtuoso piano player that we’d just gotten to know in connection to Queen. I thought, How great would it be to get all these guys in the studio and see what happens?

How tight were you with Eddie at that point?

Ed I knew as a friend, but I’d very seldom had the chance to hang out with him. I got very drunk with him one night, ill-advisedly, ’cause he could drink and I couldn’t. So I tried to match him and it was a terrible mistake. I ended up falling over in his bathroom in his hotel room… That’s another story. [laughs]

One of the great services of the box set is to give us more Eddie Van Halen playing.

I set him up. I gave him that break in the middle of ”Star Fleet,” the bit where Ed steps forward and does his own thing, unfettered by anything. That to me was the climax of the whole song. He steps in, and it comes completely out of his head. That’s not an overdub – he just does it. Every time he does it, it’s different, ’cause his brain’s constantly creating new stuff, which to me is one of the great joys of the [box set]. I love to hear the different version of what he came up with. What an extraordinary player he was. Just incredible.

Van Halen were a family and they operated as a family...Queen were pretty much the same way

Brian May

Is the box set a tribute to Eddie in a way?

Yes, it is, but I did hesitate. At the time when I was starting to think about it, it was just about the time Ed passed away, and I couldn’t do it. I just didn’t feel right about it. So I embarked on the first two solo albums proper, Back to the Light and Another World. And then a few years passed and I got to talking to Alex Van Halen, who’s a great inspiration and also a wonderful musician. He’s become a trusted friend, and I have enormous admiration for him. He’s been through such a terrible time because, of course, the two brothers were completely inseparable. For Alex it’s like losing half of himself.

So I wanted Alex’s blessing to do this, ’cause I didn’t want to do anything that felt distasteful. Now I’m more conscious than ever that I kind of stole Ed for a day or two days, and that wasn’t something that happened very often. Van Halen were a family and they operated as a family, always in the same space as a group. And, to be honest, Queen were pretty much the same way.

There’s a lot of blues on Star Fleet Project, in that Queen sort of way, in “Let Me Out” and, of course, in “Blues Breaker.” I guess whenever you get a group of musicians together, it can tend to go there, right?

Twelve-bar blues is a great place to learn to play with people. And Ed, like me, was inspired by Eric Clapton, and that’s why when everything else had been attempted, we lapsed into this blues jam, which became “Blues Breaker” and was inspired by those days. And by that time we were very relaxed. We’d gotten over our nerves and we’re not regarding each other like foreigners anymore. We’re just enjoying playing, getting in the groove and really hearing and playing off each other. It was the most relaxed we got in the studio during those two days.

Eric is on record as not particularly complimentary about it, however.

I think he hated it! [laughs] But he’s entitled. Eric could do anything and he’ll still be our hero. There’s probably lots of things I disagree with Eric about, but that doesn’t change anything. He’s been one of the greatest inspirations of my life, and that’ll never change.

So will there be a Bohemian Rhapsody sequel?

No. I think if by a miracle the right script was created by somebody, that would be a different story. But for now we don’t see a way to do it.

What about new Queen music?

Not at the moment, ’cause we’re so busy doing the other stuff. We love playing live, and Adam’s given us the ability to do that, and he kind of keeps us young, because he’s so full of energy. So we’re very engrossed in honing the live stuff, trying to introduce new elements to that. We did actually get into the studio a couple times to do various bits and pieces, but we never felt there was anything right.

There’s a lot being made about AI right now, and its potential use in the music world. That’s a technology you’ve probably been involved with and even used in your scientific pursuits, no?

It is, and my major concern with it now is in the artistic area. I think by this time next year the landscape will be completely different. We won’t know which way is up. We won’t know what’s been created by AI and what’s been created by humans. Everything is going to get very blurred and very confusing, and I think we might look back on 2023 as the last year when humans really dominated the music scene. I really think it could be that serious, and that doesn’t fill me with joy. It makes me feel apprehensive, and I’m preparing to feel sad about this.

I think a lot of great stuff will come from AI, because it is going to increase the powers of humans to solve problems. But the potential for AI to cause evil is, obviously, incredibly huge – not just in music, ’cause nobody dies in music, but people can die if AI gets involved in politics and world domination for various nations. I think the whole thing is massively scary. It’s much more far-reaching than anybody realized – well, certainly than I realized.

Does it scare you off or fuel you to do more as a human creator?

I’m always doing bits and pieces. I do a lot of guesting on people’s tracks; I quite enjoy that. But it’s like the universe is a different place now, and there are echoes of us in that place. But where we actually stand as artists, I’m not sure. We still have something to say, but methods and media are so different now. It’s kind of a struggle for us to stay on top of that, I think. We have young people around us, thank God. We ask them what to do. [laughs] The combination between different generations can produce a lot of powerful stuff. So we still have our methods, and our methods are acquired through years and years of experience, both in the studio and on the road.

The funny thing is they’ve forgotten the old methods, so sometimes when I go to someone else’s studio I say, “What if you did this?” and I’ll suggest doing something everyone would have done 40 years ago. And they’ll go, “Oh, yeah. We never heard of that!” So there is that value in the combination of the old and the new that gives you great power, and I value that. But I have to swim quite fast to keep it up. Even being able to turn my TV on! [laughs] Put it that way.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds