Brian May: The Guitar Player Interview

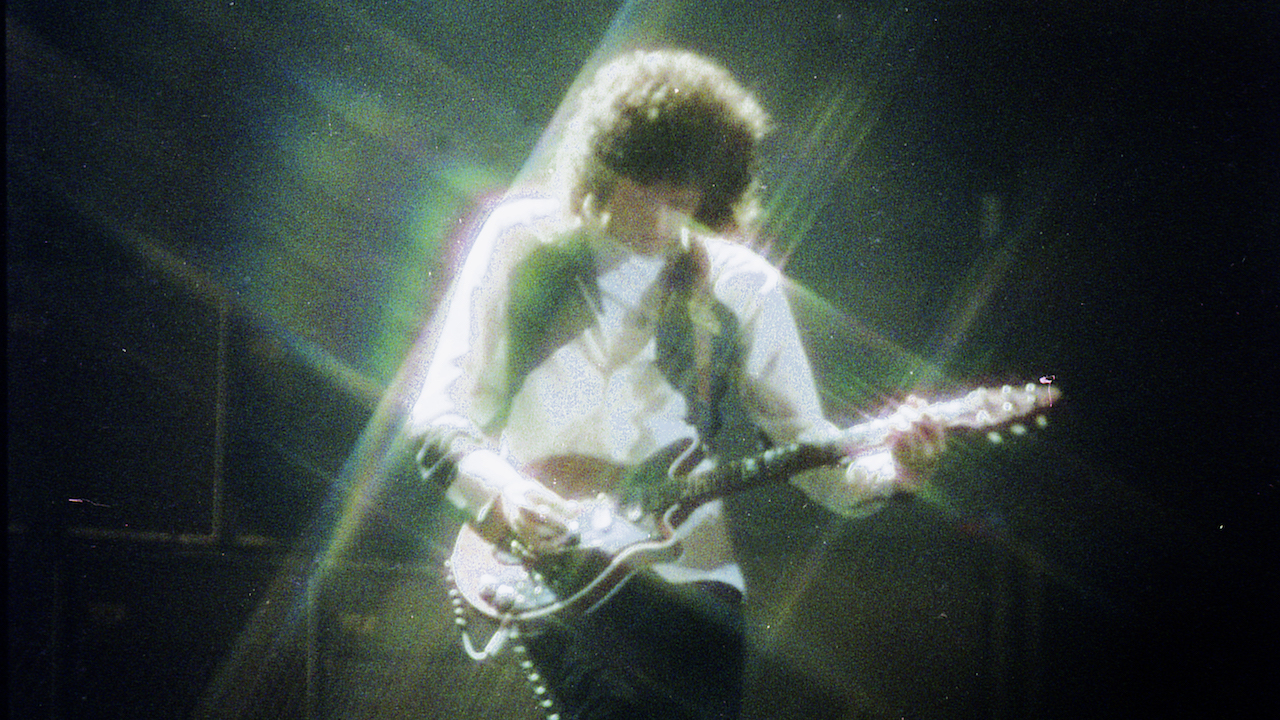

In this classic interview, the Queen guitarist talks tone, technique, his greatest moments and the Queen song he'd struggle to play all the way through

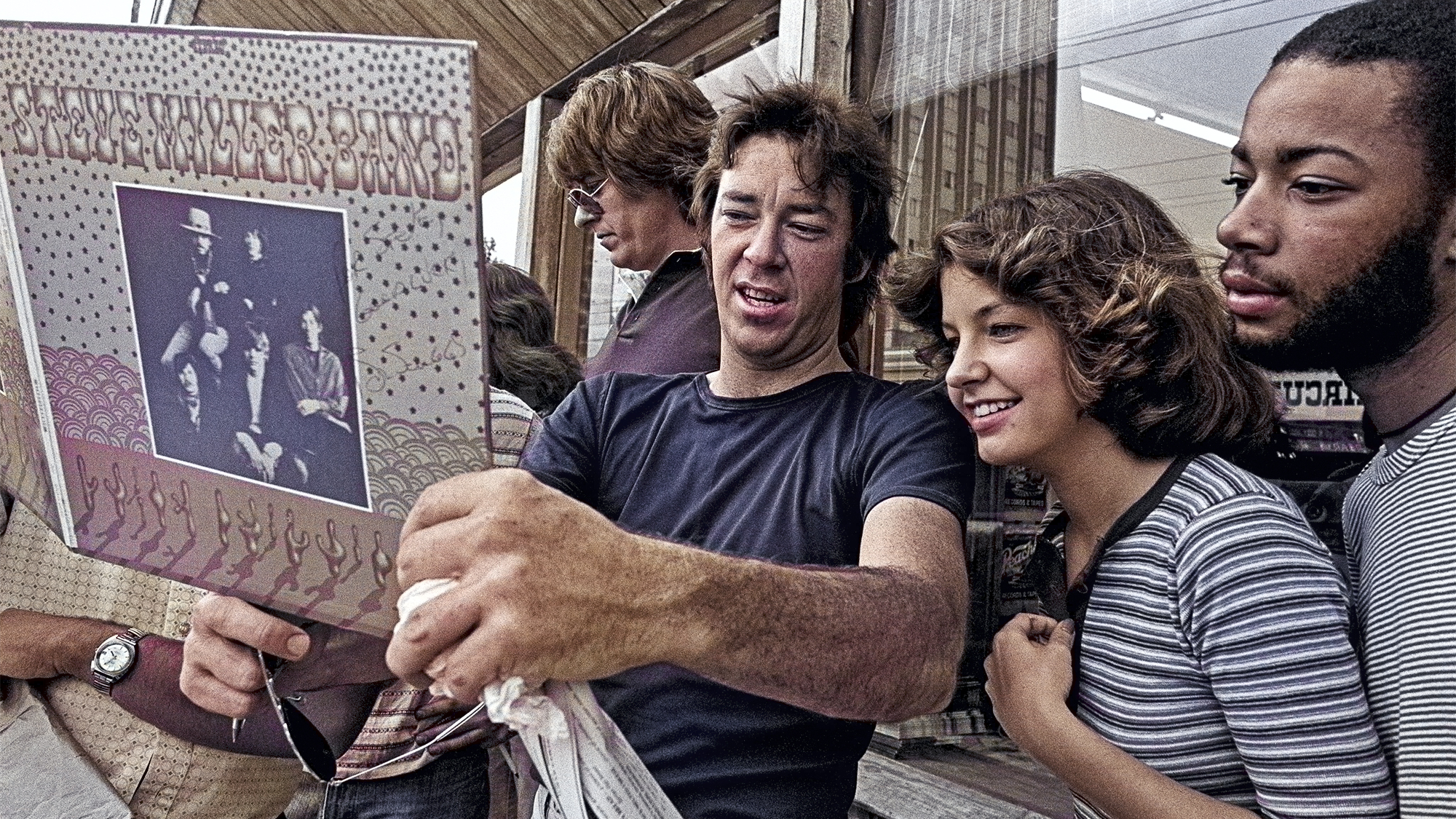

George Martin has said that you don’t have to teach children to love the Beatles. You merely have to expose them to the Beatles and they’ll take it from there, exploring the catalog, identifying with the songs, and developing a deep, lifelong love affair with the band. It has happened with every generation since the group’s inception and shows no signs of ever stopping.

The same is true with Queen.

The band obviously gained a loyal following almost instantly, with fans drawn in by the amazing combination of melody, harmony, subtlety, and bombast. Each hit single garnered new adherents, but that can be said of almost any successful band, and it generally only lasts as long as the band lasts. But when Queen’s supernaturally talented singer, Freddie Mercury, passed away in late 1991, the band’s popularity did not die with him. In fact, that’s when the first of many waves of new fans hit, beginning with the inclusion of “Bohemian Rhapsody” in the movie Wayne’s World. It happened again with the debut of the theater hit We Will Rock You. It happens every time newer artists such as Pink, Jake Shimabukuro, Katy Perry, or Lady Gaga cover Queen tunes in concert. And it will likely occur again when the Queen Extravaganza—an officially sanctioned tribute band—hits the road.

And even as new generations get hip to Queen’s music, oldschool guitar freaks continue to rediscover the wealth of 6-string magic that was created by Dr. Brian May. It’s constantly inspiring to be reminded of how lyrical his melodies are, how inventive his harmonies can be, and how freaking great his tones are. You can hear “Killer Queen” any old time. Want to really rekindle your love for Queen? Listen to his solo in “Bijou,” check out the celestial guitar choir of “All Dead, All Dead,” and revel in the absolute sweeping grandeur of May’s work in “It’s a Hard Life.” There is simply no one like this guy.

With Freddie Mercury no longer with us and bassist John Deacon firmly ensconced in retirement, it is primarily May, with help from drummer Roger Taylor, who oversees Queen’s enduring legacy. The good doctor has been busy of late, creating the album Anthems with British theater star Kerry Ellis, an intriguing fusion of musical theater, orchestra, and rock guitar. Shortly thereafter, May and Taylor acted as executive producers for the re-mastering of the Queen catalog to celebrate the band’s 40th anniversary. The old songs sound better than ever, and the bonus tracks, including the band’s first demos, are mind-blowers. One listen to those embryonic early recordings will prove to new and old fans alike that May and his cohorts had their whole trip together from the get-go, and that will ring just as true 40 years from now.

What did you learn as you went through this remastering process, both from a full band standpoint and a guitar standpoint?

I kind of marveled at it because of all that we did. It was so complex. Particularly when we got to A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races, we really were flying in terms of ideas and ways to execute those ideas. I don’t know what I learned. I don’t think as a guitar player my technique changed that much from the beginning to the end. What changed was just the experience in getting the ideas to their fruition. I look back and I see a very, very young guy on that first album making his first stabs in the studio. I’ve got to smile. I think it’s amazing that I got away with that.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The early demos are fascinating. You guys might be a little raw, but you definitely sound like Queen.

I actually love the sound of those first demos. We all prefer those to the way the first album turned out. When we made the record, we got kind of forced into this particular way of working that has made Trident Studios very famous: a clinical, very separated kind of recording with the idea that you could put the warmth back in the mix. But it was never going to work. We went along with it because we had to.

The first album at Trident was on such a shoestring budget and we would use bits of time that other people abandoned. We literally would get called at 3:00 in the morning and someone would say, “We’ve got a couple of hours, boys. Come in and do a bit.” It was a very disconnected kind of procedure.

As time went on, we actually had proper studio time. Queen II was the first time. There was a lot of exploration going on on Queen II—things we always dreamed of doing: building up guitar orchestras and the beginnings of vocal choir effects as you can hear on “The March of the Black Queen.” So, although some people got surprised at the time, when I look at our output I don’t think there’s anything too surprising. All the seeds of those ideas like “Bohemian Rhapsody” and a lot of the hits were there, in essence, in the first couple of albums. They just needed full realizing.

We went out on a few limbs. After we had gone really, really far into the complex side on A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races, we did strip it all back for News of the World, so we got “We Will Rock You” and “We Are the Champions” and stuff. That was a major departure.

Why change things up when they were obviously working so well?

We had this idea that we never should repeat ourselves, so we deliberately put ourselves in different situations of writing and recording just so we would keep moving and keep breaking down any barriers that might seem to be there. I felt another barrier was broken with “Another One Bites the Dust,” as well. To various degrees, sometimes we weren’t totally comfortable with it, and certainly Roger wasn’t very comfortable with that song. He didn’t want his drums to sound like that really, but the idea was supported by John and also by Freddie, who got brilliant passionate about how we would have this very sparse, tight little sound for the drums and everything would be very spare.

Hot Space was a continuation of that in a sense. Let’s try to, not do less, but leave more spaces and make the sounds count more when they come. So there were a lot of departures, but our basic equipment was what it was from the beginning. I don’t think we really developed new talent. We just honed what was already there.

The demo for “Keep Yourself Alive” starts with an acoustic. That was surprising. Is there any acoustic at all on the released version?

No. I think that’s a good observation. I don’t quite know why we switched. I like the old version. It’s so relaxed. It’s got such a great feel to it. From that day on, I always had this theory that it’s really not a good idea to make demos. I’m not saying you can’t use your tape recorder as a notebook. I find that very valuable. But to actually make a demo of a record you’re going to make in the future, it’s generally disastrous because almost certainly you get something fabulous at the first attempt, something which you will never be able to revisit, no matter how hard you try. The more you chase it, the further it gets away. I was never happy with any the recordings we made after that first one.

These re-mastered discs contain other bonus material, such as the guitar and vocal mix of “I’m In Love with My Car.” You really can focus on what you’re doing, and it sounds like you were playing your Burns 12-string in addition to the Red Special.

You’re right—that definitely sounds like the old Burns. I had to think about it but I would say yes. It must be in there.

Some other songs where you didn’t play your Red Special include the “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” solo, which was a Tele, “Long Away,” which also had the Burns electric 12, and “Who Needs You,” which featured that funky, buzzy nylonstring. What’s up with that guitar?

I have no idea where that guitar came from. The song just seemed to need a proper Spanish guitar, rather than a regular steel-string acoustic. So we found one and I played it but I can’t tell you what it was. I’m very un-snobbish about guitars. It doesn’t matter what they’re called or where they come from. If they sound good at that point in time, that’s it. A lot of the acoustic stuff that we’ve done was played on very cheap old things I had lying around, but I just liked the particular sound. I’ve never played anything expensive, in terms of an acoustic guitar. I know that for sure. A lot of the people around me had these wonderful old Martins and things, but they wouldn’t make the sort of noise that I needed.

You’ve talked a lot in the past about the band’s vocal blend and how that came together naturally with Freddie having the pure bell-like tone, Roger having that rasp in the upper range, and you fitting somewhere in the middle. What about your guitar choirs? Do you think they came together in a similar way, like almost by chance—the way your AC30 tone blends with the Deacy? How much of that was planned out and how much of it did you just stumble upon?

A lot of stumbling [laughs]. I would generally just try things out and see how they sounded. They’re done all different ways, those guitar harmonies. Sometimes it’s all AC30 on a particular setting, sometimes I mixed it up. In some cases, like “Killer Queen,” you’ve got one part that’s the Deacy and then one part that’s the AC30 working against each other. They just work. I found things that sounded good to me, so I went with them. But I was looking for a voice. In my search I was always looking for something that would speak to you like a human voice would. That’s the ideal for me.

You’ve talked about how you don’t generally blend different pickup combinations when you’re layering a bunch of guitars, that they just seem to take care of themselves. But do you have a favorite pickup setting with the Deacy?

I tend to settle on the bridge pickup and the middle pickup in phase—that thick sound— and I use it for a lot of things. The variation of sounds from the Deacy normally comes from moving the microphone. It’s very sensitive to where you put the microphone. So that’s the principle that molds that sound. We don’t use much EQ. It’s generally just all the sound of the amp and the guitar and where the mic is positioned.

I’ve seen pictures of an SM57 on the Deacy. Do you experiment with other microphones, too?

All kinds of different mics. It just depends on what we’re looking for.

The “guitar jazz band” in the song “Good Company” is an astounding bit of guitar orchestration. You not only nail the sounds of trumpets and trombones, but you really capture the nuances of how those instruments are played. Talk about how you did that. For instance, did you use a slide for the trombone sounding parts?

I didn’t use a slide, no. I just used bending and the tremolo. It came about because I was mad, mad keen on this group called the Temperance Seven. They were part of the traditional jazz revival that happened in England in the ’60s. Actually George Martin produced their 1961 album. The arrangements were deceptively loose sounding, and yet meticulously crafted so the right harmonic changes were always there. I just fell in love with this style of arranging and I had this dream of making that kind of sound on the guitar.

When you started layering those parts on “Good Company,” what was it like when you heard it playing back?

It was really exciting. I actually did a bit of work on it. Normally I work very instinctively, but I did go away and pencil a few things down. I tried to imagine what I would be playing if I were that trombone player, or that trumpet player or clarinet player. So I tried to make them play in a way that they would find natural. I pieced it all together with little bits of guitar through the Deacy amp using a wah-wah pedal as a tone control, just trying to get it right.

Listening closely to it on the re-master, it’s an amazing accomplishment. I’ve never heard anything like it.

I appreciate that. Yeah, I’m proud. I’m relieved that that happened. That’s on A Night at the Opera, and we were really charging the hill at that point. We had three or four studios on the go at one time making that album because there was so much to do. We had such an ambitious plan for it. I was off doing that at some place in North London while Freddie was doing vocal overdubs someplace else. Then we all came back together and played each other what we’d been working on and had a good laugh. We felt like we were breaking into new territory and really enjoying ourselves.

So there’s no slide on “Good Company,” but you do play slide on “Tie Your Mother Down” and “Drowse.” What are some other songs that feature slide?

You named the two that I would have thought of. I don’t know if there’s that much else that I played on slide. I don’t regard myself as a very accomplished slide player.

Who are some of your influences for slide playing?

Probably Eric Clapton, to be truthful, although he didn’t do much, did he? I have a couple things where Clapton plays slide. Jeff Beck. Jeff Beck is always an influence. I should say Ry Cooder but that’s not really my area.

It would seem to me that the action on your guitar would be a little low for slide, but you don’t have any problem playing the “Tie Your Mother Down” parts on it.

You’re right. It’s damn difficult to play slide on my guitar because the strings are a fraction of an inch off the fingerboard. I just have to be really gentle and not hit the frets. It’s not ideal.

In “Save Me,” you do three distinct lead breaks. There’s the acoustic part, then the harmonies that sound like they’re through the Deacy that are fairly subdued, with minimal vibrato, and then there’s the solo where you really play with abandon, particularly with your use of vibrato. Do you remember how those sections came together?

I was just exploring textures, I suppose, and trying to make it tell a story, have a development. The song has a very gentle sense to it, but it also gets to a passionate place at the end and I guess I was trying to mirror that with the guitars. It’s funny. When that album got reviewed, people said, “What happened to the guitars?” I remember feeling kind of hurt when I read that because I thought, “Actually there’s quite a bit of guitar on there.” I recently redid the song on an album called Anthems with a young lady that I’ve been producing, Kerry Ellis.

Your work on Anthems is an interesting blend of rock, orchestra, and musical theater. That doesn’t seem like it should work, but your guitar fits into it seamlessly and naturally.

To me, it’s the next step, where the guitar sits in a different place, where rock meets orchestra. Ten years of development went into that so I do feel very proud of it. It’s not a great seller—so far anyway—but I’m as proud of the work on that album as anything I’ve done. I read that Jimi Hendrix talked about that idea of combining guitar with orchestra before he died. I find it absolutely riveting when you get it right, and everything seems to organically fit together—all out guitar and all out orchestra.

Roger says that his favorite solo of yours is in “Was It All Worth It.” Are you surprised by that?

I had no idea Roger thought that. I love the track but to be honest I just had to go and play it to remind myself what the solo was. It’s not bad!

That solo is pretty technically demanding. Is it all alternate picking or do you use sweep picking for the arpeggios?

Thanks, but I don’t think it’s very technical, really. It’s just will power! I pick up and down on those arpeggios. I can do it for short periods but after that my brain short-circuits and my hand gets confused. I actually like those rising lines. I like lines that suggest harmonic content. I tend to play across chords rather than along lines.

Your first story in Guitar Player showed you with a Les Paul Deluxe, and you also played a Strat many years ago. What were your impressions of those guitars and were there specific songs you would play them on?

I don’t have much to say about them, really. I only used them as spares because I didn’t have a decent copy of my guitar at that time. Neither of them really worked for me, though they work just fine for other people. The Les Paul was too dull, the pickups whistled, and it had no trem. The Strat sounded painfully thin and didn’t sustain the way I wanted. I kept thinking, “It worked beautifully for Rory Gallagher with a similar amp setup.” But for me it was just frustrating. In time we got the BM guitar copies going, and my problems were solved.

What were your impressions when Greg Fryer presented you with the replicas that he made of the Red Special?

I was very happy. He’s an amazing guy. He made three of them, and they are stupendous. We call them John, Paul, and George. He kept Paul and I kept John and George. John is the one that I use most and George is the one I have at home to play. George is the prettiest of the three, with a lovely marbled veneer. They’re wonderfully made. His attention to detail was absolutely top class.

Was it nerve wracking to have him work on the real deal?

You mean when he took my guitar to bits and had it in pieces all over the workshop? I did have a moment of catching my breath because that had never happened since I made it. But I quickly learned to trust this guy. He’s an amazing craftsman and he took infinite care. He had to take it all to bits to take all the measurements he needed. When he finished, he put the new guitar into my hands, and if I closed my eyes I couldn’t tell it wasn’t mine. It’s amazing.

Your Red Special has great intonation, even when you’re playing full chords at the 14th position in tunes like “Hammer to Fall” and “We Will Rock You.” How did you and your dad achieve such precise fret placement, especially considering the fact that the 24” scale length is different from Fender’s and Gibson’s?

I did the calculations for the frets on the computer I was working with at the time in my work place. This is about 1964, and a mainframe computer filled a large building, with an overall capacity of about a thousandth of your laptop. I made up my own formula, and based my program on an iterative solution to the equation. The calculations were correct to 24 decimal places. Really! I have the printout somewhere.

How did you come to include a zero fret? Why don’t more manufacturers use them?

The zero fret is part of the plan for good intonation and return from whammying. I got the idea from my small acoustic, but it made the business of minimizing friction at the nut much easier. It works. I’m really surprised that so few people have followed that up.

Freddie tended to write in non-guitar keys. Did that pose any challenges for you?

Absolutely. It made me play in different and unusual ways on the guitar. It was definitely a big influence on the way that my style developed. You get used to playing in Eb and F and all the keys which your fingers don’t want to work with. It’s very formative. It really made me find all sorts of shapes that I never would have found otherwise.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is certainly in line with that. You’ve talked about how the ending bits in that song are tricky for you to play. Are there other pieces or sections in your catalog that you find challenging to perform?

Probably “Millionaire Waltz.” I don’t think we’ve ever managed to play that all the way through. I had a lot of fun with We Will Rock You, our musical, because I have a couple of great guitarists and a keyboard player that can sound like a guitarist if we ask him to. I’ve had a lot of fun rearranging some of our stuff to be played live, in a way that I wouldn’t be able to do on my own. But obviously some of the stuff we did on record is so complex it would take ten guitars at once to actually reproduce it.

Much has been written about your lead work and as a result your rhythm playing doesn’t get talked about as much. What can you say about the attention you put into being a great rhythm guitarist?

Ooh…you used the word “great” [laughs]. I take rhythm playing very seriously because for me, the guitar is a lead instrument and can be a voice, but it has to be always playing underneath the vocal. This is what I tell my guitarists all around the world who play in We Will Rock You—be free and be creative, but always remember that if you’re doing something that messes up the vocal, you’re in the wrong playing field. So with rhythm guitar, you have to do things that are complementary to the vocal and to the song. If they get in the way, you’ve lost the game.

I love playing rhythm and that’s the way I started. When I was a kid I just played acoustic guitar and strummed and sang. I sang Everly Brothers songs, Tommy Steele songs, Elvis songs—so rhythm guitar is where I come from. That doesn’t tend to happen to people these days. People go straight into the widdly widdly things and they don’t really have time to get settled as rhythm players. I’m very lucky because with the AC30 and my guitar and the treble booster I can have an infinite adjustment between clean and totally distorted. That smooth transition is so useful for playing rhythm because you can make it sound big without it becoming a horrible mess. It’s just enough in just the right way to make it envelop and yet at the same time be sweet.

You mentioned your acoustic strumming. That was on display in the tune “39,” which you sang on A Night at the Opera. Yet on Live Killers and also on the live bonus tracks, you’re not singing it. Freddie’s singing it. Was that so you could focus more on the driving quality of the acoustic rhythm?

Live, it seemed a crime not to have Freddie singing. I could have sung it, but you’ve got one of the best singers in the world there so why not use him? I’ve come to the conclusion, at the end of a long road, that I’m not really a singer and I can play much better guitar if I’m not singing. There are people who can sing and play at the same time, but maybe they’re just not me. If I have a singer standing beside me, I can concentrate on making the guitar speak.

What do you think about the fascination that guitarists have with your signal chain and your tone?

It’s very flattering. It surprises me sometimes. I’m constantly amazed when people like Joe Satriani or Steve Vai—people who can play me out of this universe—say they get excited about what I do. That means a lot to me. I think it’s down to the fact that people feel something when I play. It’s a voice. If there is something special there, it’s because it’s very direct and most of the time it’s very uncomplicated. I try to speak through the guitar other than just playing notes. But it’s very hard to answer what people might like about things. It can only be because there’s some speaking going on there through the guitar.

I recently heard a couple of tunes from your pre-Queen band, Smile, and I was surprised at how heavy they were. You were really interested in powerful, heavy guitar work from an early age. What led you to that approach?

I think we all have our heroes and we all have those moments where we get excited and think, “That’s what I want to do.” So it’s a mixture of all that. For me, it probably starts with James Burton playing on Rick Nelson records and little bits and pieces I heard on Everly Brothers records, and it develops. It goes through the Shadows and Hank Marvin’s amazingly lyrical and beautiful sound, and then the beginnings of that explosion—Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck. I was inspired by that, but I was also always inspired by harmonic and melodic content.

I talk about the Everly Brothers a lot, and Buddy Holly and the Crickets. Those harmonies electrified me. They are quite simple, but they just hit the button. Forever I was looking to records and unconsciously figuring out what everybody was singing, so I could sing all the parts on those records when I was a kid. My dream was to combine melody and harmony with a real uncompromising heavy undertone.

Then I met Roger and he had a similar feeling about music, and Freddie as well. John came to us with a slightly different emphasis but he very much got into developing the dream. We were very lucky to find each other. It was a very organic combination of people. We just worked together really well.

Did Smile open for Hendrix?

We played in the same building but not in the same room. Actually, it wasn’t Smile. It was a group called 1984, which was before Smile. We played in the bottom refectory part and Jimi played in the great hall upstairs, which held about 1,000 people. People tell me that Jimi came in and saw us playing, and at that time we were playing “Purple Haze.” I don’t know what he thought. He probably shook his head and went off and had a laugh. But later we went up and saw him play and it was indescribably huge. I’ll never get over it. It was just beyond amazing. You couldn’t imagine how that kind of sound could come out of three people—the Jimi Hendrix Experience. It was colossal.

How does it make you feel to see younger artists like Pink, Jake Shimabukuro, and Lady Gaga pay tribute to your music and expose their fans to it?

It makes me unquestionably happy. Pink’s version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” impressed the hell out of me. I think it’s amazing. It’s the greatest accolade you could have that people in different generations—who are essentially peers, but in different years of time—come in and appreciate you. It’s the best thing that could happen, and it makes me feel very good.

Roger Taylor on Brian May: "When you hear Brian, it could only be Brian..."

Queen drummer Roger Taylor knows a thing or two about extravaganzas. He’s the guy, after all, who brought not just gongs but tympani on tour back in the ’70s. He sang those high-pitched Galileos. He’s in love with his car. He’s Roger F*cking Taylor and you’re not. So who better to choose the players and singers for the Queen-approved tribute band that will tour as the Queen Extravaganza? From a bunch of great candidates, Taylor went with Tristan Avakian and Brian Gresh to fill the guitar roles. He talked to GP about this, about his guitar collection, and about what he thinks about the guitarist he’s worked with for more than four decades.

Explain your overall concept here. What were you going for with this Queen Extravaganza?

I really got tired of seeing our music presented in the form of tribute bands, often represented as cheesy, small scale, and not very well done. I thought, “Why don’t we get our own tribute together and produce the show ourselves and throw our own energies into it?” We know our music better than anybody and I want to see it represented to people in an excellent and spectacular way.

What were you looking for in a guitarist? I’m guessing it wasn’t enough just to be able to play Brian May licks.

I didn’t want impersonators. I wanted people with their own personalities. Obviously you need a certain amount of proficiency because Brian’s stuff is very technical. I also wanted people to have a little bit of showmanship. I think that is very important.

How much deviation from Brian’s parts would be too much? It would seem like there are certain things that absolutely need to be there.

Take a song like “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” I would expect the main guitar solo to be note for note, but then at the end, we let them go off and show what they can do.

When I watched the YouTube videos for the guitar finalists, many of them seemed to be better lead players than rhythm players. Since you’re a very rhythmically oriented guy, what was your take on the rhythm guitar playing of the finalists?

That’s a good question. You tend to look at their lead playing abilities first because Brian is best known for that, I suppose. There was quite a variation in rhythm playing. Some were definitely better than others, but I think we got the right guys.

When I asked Brian about when you two met, he remarked at the tone of your drums and how you meticulously adjusted them so they were all in tune with one another. Were you struck by his style and his sound as well?

Absolutely. I had worked with quite a few guitar players, and he was so much better than any of them. He’s got this touch—you’ve either got it or you haven’t. It’s this bending touch and melodic touch, which I think makes him a unique player, and that contributes to his sound. Plus of course there’s that little fireplace he plays on. It’s a great-sounding, unique guitar. But it’s really in the touch. It’s like Jeff Beck. It could only be Jeff Beck. And when you hear Brian, it could only be Brian.

Do you have a favorite Brian May solo?

Yeah I do, actually. It’s a very obscure song called “Was It All Worth It.” It’s got a killer solo on it. “Bohemian Rhapsody”—that’s quite a solo on there. I guess “Killer Queen” has one of my favorite solos, as well.

You’re a guitarist yourself and a guitar collector. What are some interesting pieces in your collection?

I have a very early Strat, which I believe is the most valuable in the collection. I have a Broadcaster, serial number 017. That’s obviously very early, before the Telecaster. I just got a Gretsch Duo Jet, and I love that guitar. I have an interesting guitar collection. I think I’ve got more than Brian, actually. But I don’t play them like he does.

This interview was first published in Guitar Player in April 2012.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.