"Every kid who picks up a guitar wants to be Keith Richards, right?" How Andrew Watt kicked Keef and Mick Jagger "up the ass in the studio," connected the Stones back to Muddy Waters, and recruited Paul McCartney for a punky cameo on the band's new album

Andrew Watt has made records with Ozzy Osbourne, Iggy Pop, Pearl Jam, and more, but manning the boards for the Rolling Stones' Hackney Diamonds was, he says, "the honor of my lifetime”

"So who does every kid that picks up a guitar want to be?” producer Andrew Watt asks. “You want to be Keith Richards, right? That’s the whole fucking thing! So making this record and working with the Rolling Stones, earning their trust, was the honor of my lifetime.”

Watt, at 32, is still a little giddy from working with the World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band on their new album, Hackney Diamonds, and who can blame him?

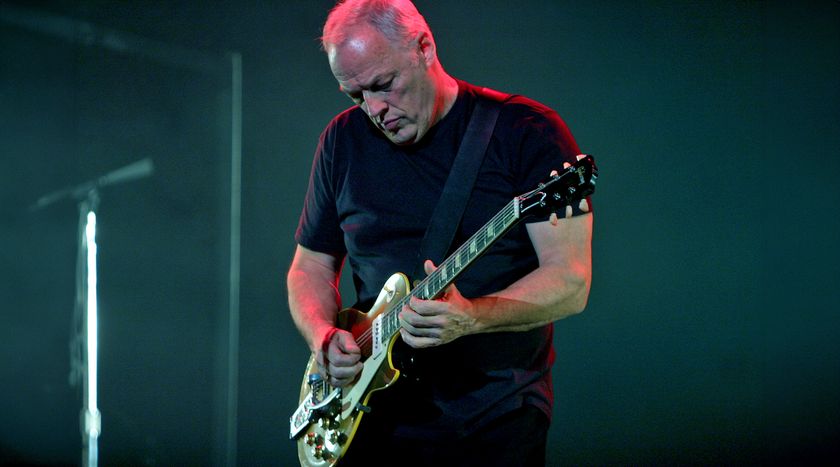

Even though he’s arguably the music industry’s hottest producer, having collaborated with everyone from Ozzy Osbourne to Eddie Vedder to Miley Cyrus, the native New Yorker is still buzzing from his time producing the Stones and their legendary guitar duo of Richards and Ronnie Wood.

“I’ve seen the Rolling Stones play countless times,” he continues. “I said to Keith, ‘It’s like you plucked a freak from behind the barricade and let him produce your album.’”

Watt is a fanboy for sure, and his enthusiasm — not to mention his impressive collection of electric guitars and amps — resonates throughout Hackney Diamonds, arguably the Stones’ best work since 1978’s Some Girls.

But despite his genuine love for the band, he was no pushover, prompting singer Mick Jagger to comment, “We got a producer called Andy Watt who kicked us up the ass.”

Watt told Guitar Player just how hard he put the boot in...

How did this project come together?

In our initial conversations, the band explained that they were facing some creative roadblocks. There was a lot of stop-and-start in their initial process, so it became my job to help facilitate slamming the ball in the end zone.

It must’ve been intimidating to tell Keith Richards to get his ass in gear.

I don’t think that ever happened. He’s armed with a knife at all times! [laughs] But the band had given me a clear directive, and in my line of work, results are what matter. So I didn’t waste time bullshitting. I just tried to make it clear that it was time to focus and get to work.

How did you do that?

I had a bass and just started playing with Keith. I was of the mind that if I could earn his respect as a player, then I could communicate with him musically and offer suggestions chord-wise or inversion-wise or tone-wise or whatever. And we just got into it.

Then, when we started recording the basic rhythm tracks in L.A., I sat next to Keith in the live room across from Mick and Ronnie. That was an extremely important part of the process for me. I wanted to make sure the sounds were good, and as we were going through the takes, I was able to remember the performances, because I was right there. If we got a good take, we just moved on immediately.

After we did the basic tracking of roughly 23 songs, we got into overdubs. I think it was during the overdub sessions that I really earned Keith’s respect and trust. It was very important to me that all of his parts were done before Mick added his final vocals, and we really worked hard together to accomplish that.

What was it like to work with Keith and Ronnie? How prepared were they, or did you guys work out arrangements in the studio?

Many of the songs had been developed over time. So after we listened to whatever the most recent demo was, everyone would start familiarizing themselves with the song, and we would play it a few times until everyone had it down cold.

And this is where it gets interesting: Instead of using the final take, we would use the previous take, because it still had that spark of spontaneity — the take where people were still searching.

The worst part of contemporary music is how producers often kill a performance in search of perfection.

I make loop-based music with some of my other clients, but I don’t want to hear the Stones like that. No one wants to hear the Stones on some grid.

Can you talk a bit more about how Keith and Ronnie work together?

Listen to a classic Stones song like “Beast of Burden.” You can’t tell who’s playing lead and who’s playing rhythm, and if you muted one of them, it would sound sparse. They fill the holes together so beautifully, and that’s apparent on the whole record.

Take a song like “Angry.” They pause to exchange licks, one handling the rhythm while the other responds. They watch, listen and engage in this incredible musical dialogue. If you want to really check it out for yourself, I purposely mixed it so 90 percent of Keith’s parts are on the left and Ronnie’s are on the right.

There are at least two tracks I’d love to know more about. The first is “Bite My Head Off,” featuring Paul McCartney on that gnarly fuzz bass.

This is part of a much longer story, but essentially, I was working with both Paul and the Stones during roughly the same period. The Stones’ regular bassist, Darryl Jones, isn’t on the album at all because he was on tour, so everybody was taking turns playing bass, including me, Keith, Ronnie and Bill Wyman.

One day, while speaking with Paul, I thought, Why not invite him to play bass on a song? I realized it was a significant request: Can we get someone from the Beatles to play in the Stones? But surprisingly, both Mick and Paul were like, Sure, no problem, sounds like fun. They were so nonchalant.

I reviewed the list of songs slated for recording. The typical choice might have been to place him on one of the ballads, such as “Dreamy Skies.” However, I thought, how cool would it be to play on the most aggressive punk-rock track on the album? I knew Paul loved to rock, and they had a great time recording “Bite My Head Off.” They were all laughing like teenagers.

How did Paul achieve that fantastic distortion on his bass?

As Paul and I were becoming friends, I decided to get him a gift. I got him another lefty ’64 Hofner, similar to the one he played in the Beatles. However, I added a twist: my guitar tech installed a Univox Super Fuzz circuit on the Hofner that could be activated with a switch.

When I gave it to Paul, he said, “This is an incredibly thoughtful gift, but why? I already have my Beatles Hofner — why another one?” I was like, “Just plug it in and give that extra switch a try.” Suddenly his eyes widened, and he just started ripping on it. I told him to bring it to the recording session, and he couldn’t stop laughing.

I shared the song with Paul the day before, and when we entered the studio with the band, he brought out the bass. During the breakdown section of the song, he activated the Super Fuzz switch, and it was complete carnage! Everyone was like, “What the fuck was that?” It was hilarious and so cool.

I think we recorded just three takes of that song, but almost immediately, Keith and Ronnie were on their feet, and Mick dragged the mic into the middle of the room and the roof left the building.

I think Paul really enjoyed that he was just a guy in a band again with friends that he’s known for 60 years. It had been a long time since he was with equals, just plugging in his bass and doing a session. I couldn’t wipe the grin off my face for a very long time.

Did Keith and Ronnie use any unexpected guitars or amps on the album?

Keith brought in his usual amp rig, which consists of four amps that he’s been using for a long time — a setup that’s well documented. However, just to switch things up, I brought in five amps that had been worked on by the late and legendary Howard Dumble. Keith was particularly drawn to one of the Dumble-modified 1958 Fender Twins, which he used for a bunch of his overdubs. It just had a magical sound.

Also, in addition to his ’54 Tele and Gibson ES-355, Keith also played a Dan Armstrong guitar on a few tracks. One of my all-time favorite performances by Keith is a version of “Midnight Rambler” at a gig at the Marquee Club in 1971.

You can watch it online. He’s playing a Lucite Dan Armstrong guitar, and it sounds incredible. Unfortunately, it was stolen years ago, so I bought a ’69 just like it and brought it in, and he used it on some tracks.

Keith also used a ’55 TV Yellow Gibson single-cut Les Paul Junior on “Angry” and “Mess It Up.” Ronnie used the Junior on “Bite My Head Off,” but most of the time he played his Strat, which is either a ’54 or ’55, and the Zemaitis he used on the Faces’ hit “Stay With Me.” It was pretty funny.

Every time he plugged the Zemaitis in, we’d make him play “Stay With Me,” and everyone would sing along at the top their lungs.

One of the best tracks on the album is Mick and Keith’s powerful duet of Muddy Waters’ classic “Rollin’ Stone” [called “Rolling Stone Blues” on the album]. From what I understand, that was your idea.

Yeah. During our overdub sessions, Keith and I started talking in a more personal way. One day I just asked him how he met Mick, and he told me the story. He said he saw this kid getting on the train in Dartford and under his arm were two albums: The Best of Muddy Waters and the first Chuck Berry album.

Both were Chess Records imports, which were almost impossible to find in England at that time. Keith said, Mick “was either going to be my best friend or I was going to rob him.” [laughs] They, of course, wound up being best friends and started playing together.

But The Best of Muddy Waters was important for another reason. One of the tracks on the album — “Rollin’ Stone” gave the band its name. The idea of asking them to play that song didn’t hit me right away, but the germ of the idea was there.

I just asked the dumbest question: Have you guys ever played ‘Rollin’ Stone’ before? Keith thought for a second and said, ‘No!’

So when did the idea of having Mick and Keith play “Rolling Stone Blues” click?

It didn’t happen immediately. One day, while hanging out with Keith in New York, he was sitting with me talking. But I found it hard to focus on his words because he had an old Martin acoustic in hand, and he was playing the most primal blues I had ever heard in my life.

Not many people can play blues like that. Robert Johnson could, Muddy Waters could, and Keith Richards certainly can. He seemed possessed by something, channeling the essence of the blues.

It wasn’t about complexity; it was about having it in your soul, and Keith had it in spades. It was surprising. I never really thought of him playing a slow Robert Johnson blues, but it’s what he really loves. So I made a mental note of it.

After that experience, I told Mick that I thought he and Keith should do a straight acoustic blues for the album. Mick found the idea intriguing but was initially noncommittal, given the many other songs we had to complete.

But as the record started falling into place, I pushed him again on the idea. Sometimes that goes well, and other times it does not. [laughs]

Suddenly, I heard a change in his voice, and he said firmly, “I have 23 songs I’m trying to write the lyrics for. I don’t have any blues lyrics.” So I retreated a little bit and didn’t push. That’s where things stood with Mick.

So what led to the change?

At one point, Keith began telling me the story about how the band got its name, and as he was telling me that, I just asked the dumbest question: Have you guys ever played “Rollin’ Stone” before? He thought for a second and said, no they hadn’t — which sorta surprised him.

They had played every other Muddy Waters song, but ironically, never that song. And that’s when I pounced and asked whether he would consider playing it for this record. Keith said he knew it backwards and forward, but the decision ultimately rested with Mick.

I said, “Give me a second and I’ll call him.” So I went in the other room, and I called him. I was excited and said, “You don’t have to write any blues lyrics because you can just tackle Muddy’s ‘Rollin’ Stone.’”

There was a long pause on the phone. At first, I thought he was going be angry that I was pushing the blues idea again, but then he just said, “Okay, when do you want to do it?” We were finishing up our overdub session, so I suggested doing it that day.

As Mick made his way to the studio, Keith began playing the song. And now the hairs were raising on everyone’s arms in the studio. They were finally going to record the song that inspired the band’s name.

The sound of Keith’s guitar is so powerful on that track. How did you accomplish that mixture of acoustic resonance and electric distortion? It’s undeniably unique.

I made the decision with Paul Lamalfa, my engineer, that we would record on tape, because there was no better way to capture the essence of the moment. The goal was to capture the magic of two musicians in a room.

We aimed to re-create the vibe of Muddy’s original recording, and if there were ever two guys who could do it, it was Keith and Mick.

Keith, along with his guitar tech, Pierre De Beauport, and I listened closely to Muddy’s original recording as a reference. We were like, “Is that an electric guitar?” It seemed unlikely; he was playing acoustic back then, yet the sound was so heavy because of the way he played and how it was recorded.

So I said, “I have an acoustic 1930 Gibson L-4 with me,” which is like the L-1 guitar associated with Robert Johnson. Keith was like, “Oh, let me see it.” And so he started playing the song. He could play it beautifully, but it’s not an easy guitar to play. It was made before guitars had truss rods, so there was no way to really adjust the action.

But this is when the universe does its thing.

We started looking at these two pictures of Robert Johnson. There’s the one of him with a cigarette, and there’s the other one of him with the hat [shot from] further away. And we noticed in the photo of him with the cigarette that he had a capo on the second fret of his guitar. Keith caught that. So we all asked, Why is there a capo on the second fret? What does that mean?

Most Robert Johnson songs are in the key of E and A. We theorized that maybe he tuned down the guitar a full step, to D, and put a capo on the second fret to bring the guitar back up to E so that the strings were looser and he could play and bend easier. So Pierre did exactly that with the L-4, then he handed it to Keith, who found it played effortlessly — like butter.

Then we debated whether to record using an acoustic or an electric guitar. Meanwhile, Mick was on his way, and we needed a plan. Ultimately, we settled on trying it both ways and deciding later. We set up microphones for the L-4’s acoustic sound, and Pierre added a lipstick pickup to it, so we could rout a signal through all four amps in Keith’s setup, located in another room.

The funny thing was, the volume was so loud from Keith’s amps that the electric sound from the other room began bleeding into the acoustic mic, creating a fantastic blend.

Mick used a bullet microphone for his harmonica, that we routed through one of my Dumble-modified Fender Champs from the ’50s. He also used another mic for his vocals. However, as they played, Mick kept moving closer to Keith. Then Mick stood up, rendering the vocal mic unnecessary because he was right next to the room microphone that was capturing Keith’s guitar.

Ultimately, the recording consisted primarily of this single room mic, along with a subtle mix of the four amps and a touch of the bullet microphone, which added an extra layer of edge to the harmonica.

Neither of them wore headphones. It was simply the two of them, playing together. By the fourth take, they began to anticipate each other’s moves and complete each other’s musical sentences. While Keith crafted guitar licks, Mick responded on the harmonica, and they synchronized perfectly. It was an incredible demonstration of their yin-and-yang chemistry that had been developed over six decades.

Without overstating it, I feel this recording encapsulates the essence of their enduring relationship.

You were a witness to a genuine moment of music history.

It was heavy. It’s probably the most important thing I’ll ever record.

Hackney Diamonds by the Rolling Stones is out now and available to buy or stream

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Brad Tolinski was the Editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. He is the author of Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.

"Shredding is like talking a foreign language at 10 times the speed of sound. You can't remember anything." Don Felder reveals the unlikely influence behind his iconic guitar solo for the Eagles' “One of These Nights”

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first