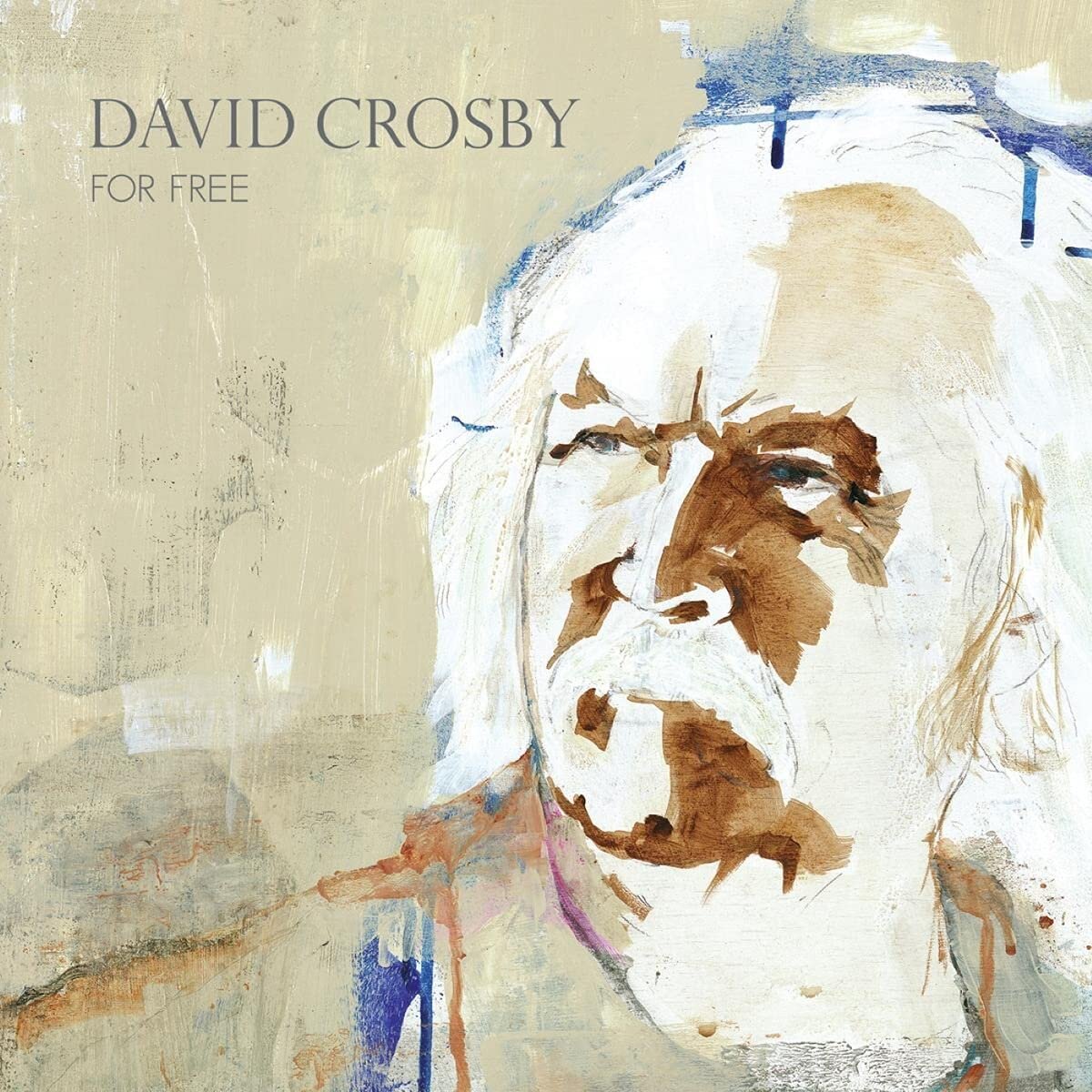

"Albums Are Still Our Art Form... They Are What We Are Going to Leave Behind”: David Crosby on His Epic Recording Legacy

The acoustic legend delivers guitar insights into his classic period and final album, 'For Free'

***This article was originally published in the October 2021 issue of Guitar Player***

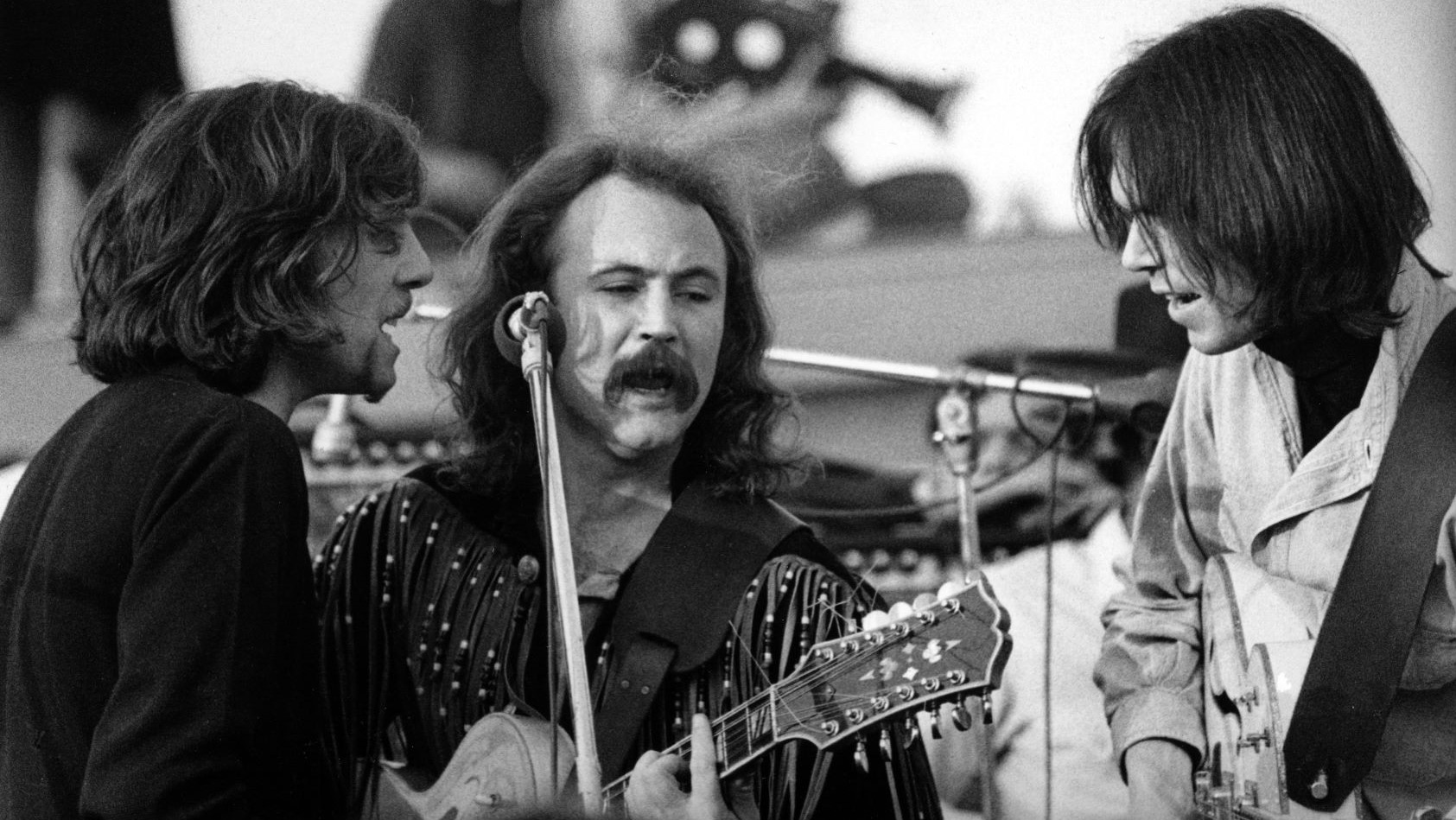

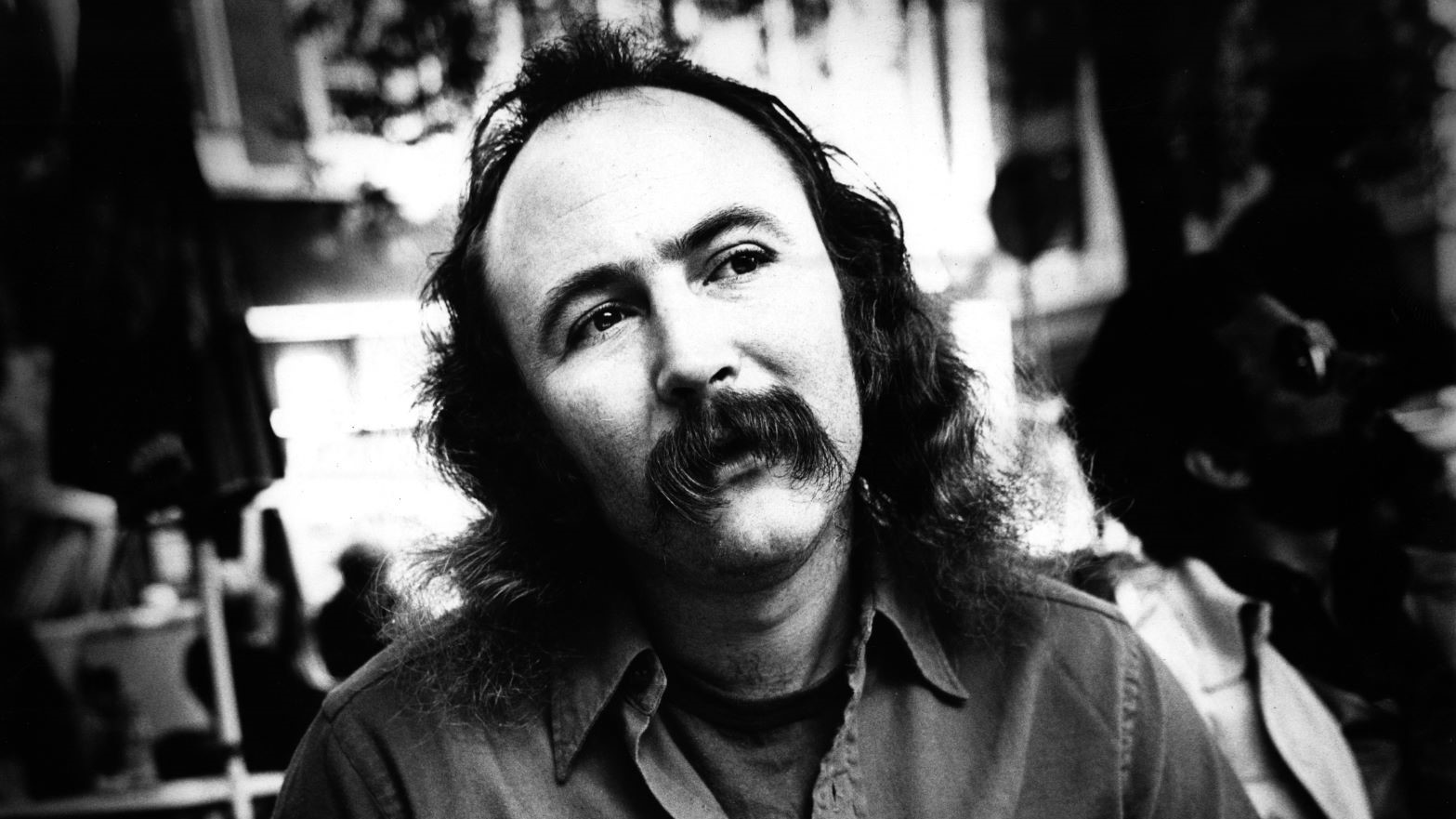

David Crosby is an iconic acoustic captain at the helm of his ever-fantastic ship, always listening for a song on the wind that might lead him to some mystical, musical port of call. More than ever lately, he appears to be a man on a mission, perhaps making up for lost time.

He’s dropped five albums since 2014. Snarky Puppy ringleader and bass ace Michael League produced 2016’s Lighthouse, and they’ve continued a working relationship that Crosby regards as a band.

Otherwise, the guitarist’s primary co-captain is his son James Raymond. Crosby refers to their collaboration as Sky Trails, which is the title of their 2017 album, and James also produced the new album, For Free (BMG).

The colorful folk-rock legend sounds almost too good for having lived a pirate’s life. His voice is unbelievably unweathered. His fingerpicking and signature six- and 12-string sounds are well intact, but as Crosby reveals in this feature, there is trouble on the horizon in the form of treacherous tendonitis.

Before sailing into the sunset, he’s being as creative as possible. What he hasn’t been doing is working with the company of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. It’s well documented that much love has been lost on that front. No more new musical magic is expected from the quartet, but there is a fantastic new 50th anniversary boxed-set edition of Déjà Vu featuring insightful guitar-and-vocal demos and extensive liner notes by Cameron Crowe.

What we can expect at some point, according to Crosby, is a major documentary produced by Nigel Sinclair and Tim Sexton (Sinclair recently produced the stellar Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart).

For Free gets its title from the Joni Mitchell classic that Crosby covers on the new album. He credits her for opening his eyes to alternate tunings, which he still uses to create deep, cosmic textures.

“I Think I” is a crafty composition with exceptional acoustic guitars and vocals that exemplify Crosby’s breezy, existential vibe. Steely Dan fans will dig the funky groove and jazzy changes on his collaboration with Donald Fagan, “Rodriguez for a Night.”

Clever electric guitar comes courtesy of session legend Dean Parks (Willie Nelson, Paul Simon, Steely Dan), who also wrote the music for the soldier song “Shot at Me.” There are some catchy commercial hooks here as well, including “River Rise,” which features backing vocals courtesy of another cat from the Steely Dan camp, Michael McDonald.

Most cuts feature Crosby’s acoustic at the core, and he’s a better guitar player than he often gets credit for, considering how much attention is paid to his voice and character. He’s actually quite humble about his playing and understands why most of the guitar cred from his crew has gone to Stephen Stills and Neil Young.

“Naturally it would go to them, man,” he says. “Those guys are lead players and have different levels of competency.”

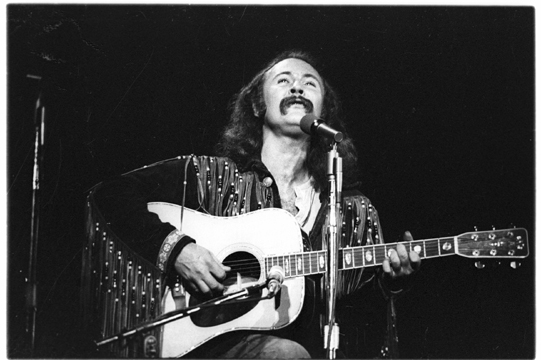

Crosby is a true acoustic guitar aficionado, and he can’t help himself from boasting a bit about his awesome collection. He still uses most of it, including his classic Martins from the Woodstock era.

Perhaps his most infamous Martin is his six-to-12-string conversion D-18. Martin has released limited-edition signature versions, first as the D-18DC in 2002, and then as the D-12 David Crosby, featuring a reversed string course in the third slot, in 2009.

Guitar Player fortuitously caught up with Croz on the heels of recent features with other notable 12-string appreciators from his generation, Leo Kottke and Taj Mahal.

How did your six-string roots start you down the 12-string path?

It’s an interesting story. The first guitar I bought was made by a banjo company that produced a 12-string guitar. Bob Gibson [an American folk singer and a key figure in the 1950s/’60s folk revival] played one, and he was one of the folk guys I liked, so I got one too.

But the first good one was a Martin D-18 that I bought at a music store in Chicago when I was living there. When I moved to California, I took it to Jon Lundberg in Berkeley and asked him to convert it to a 12-string because I was entranced with 12-strings. He did, and to this day it’s the best.

Kottke is going to argue with me about this, but I have a handful of the best 12-strings existing in the world. That one is still the king. It’s better than my D-45 12-string from the Martin Custom Shop, which is killer fucking good. Or my Roy Smeck Gibson that the folks at Alembic converted into a 12-string, and that looks exactly as if there had been a Roy Smeck Gibson 12-string.

Or the copy Martin made of my D-18 for the prototype of my signature 12-string. That has an ebony neck, and it is still hanging on my wall. I truly love 12-strings, and the best one I’ve ever had is still that first one.

Why?

Every single one is different, like snowflakes. Maybe it’s the wood combination. Maybe it’s all the love I’ve poured into it over the years. I’ll line them all up and let you play them, and you’ll come to the same conclusion. Although I’ve got to say that the D-45 rings like a bell.

Every single one is different, like snowflakes. Maybe it’s the wood combination. Maybe it’s all the love I’ve poured into it over the years.

David Crosby

The original modified D-18 has 12 frets to the body, correct?

Yeah, that puts the bridge a little further back, and for some reason that works. I don’t know why. It is what it is.

What inspired you to have the modification done in the first place?

It was the sound of the guitar. It sounded so good as a six-string, and I should have left it like that, but I was enthralled with the 12-string, so I took the chance, and it worked, out of sheer luck.

Why were you so enthralled with the 12-string? Who was turning you on at that time?

Bob Gibson and Pete Seeger are the two that jump to mind. I just liked 12-strings right away, and I still do. I was playing that D-18 conversion last night.

It’s interesting that you come to the 12-string from a folk perspective and wind up in the Byrds, perhaps the most famous jangling-rock outfit ever, yet you jump to an electric Gretsch six-string and Roger McGuinn does all the jangling on a 12-string Rickenbacker, correct?

Yeah, it’s not me, it’s Roger. He was always a much better guitar player than me. When he got one of the first Rickies, it sounded like a glass avalanche. Unbelievable. He’s such a gifted musician. He basically does one thing, but he does it really well. He’s also brilliant at voicing something into a different form, like turning “Mr. Tambourine Man” from a terrible goddamned demo into that brilliant record.

I started out playing a Gretsch Tennessean in the Byrds, but then switched pretty quickly to a Country Gentlemen, which was a better guitar.

Yeah, Stephen and I are both crazy about acoustic guitars. Graham likes them, but it’s not quite the same. Stephen and I kind of worship them.

David Crosby

Even more interesting is that you wind up returning to the acoustic for the act that defines folk rock, Crosby, Stills & Nash. In fact, you all start out on acoustic for that, right?

Yeah, Stephen and I are both crazy about acoustic guitars. Graham likes them, but it’s not quite the same. Stephen and I kind of worship them. We love them a lot. We each have multiple stunning guitars, and that’s why we fall in love with them. I have five Martin D-45s.

What were you thinking when Martin re-introduced the D-45 in the late ’60s?

We knew that Martin had the best wood stashed, because they’d been buying it before anybody else, and that they’d uncorked their stash of Brazilian rosewood, which is now gone. And they had a stash of top wood that they thought was their absolute best. They combined them, and that was irresistible to us.

We could get one for about five grand, and as far as we were concerned that was the best guitar anybody was making. I think we were right. I have three of those 1969 D-45s. They’re the ones with all the wear from being played at the concerts. I also have one made of koa, and it’s a mind-boggling guitar with an unbelievable sound.

Can you share the story of “Wooden Ships” from the Crosby, Stills & Nash debut in 1969?

I wrote it on that 12-string [longtime tech John Gonzales says Crosby refers to the guitar as “the Wooden Ships 12-string”]. I’d say that 90 percent of the chord changes are mine. I brought the music to Stephen and Paul Kantner. Stephen added a couple of very significant changes that really helped.

We were on my boat in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I was docked at a friend’s house and they both came down to visit. We wrote it right there, sitting in the main cabin. Paul gave me some key lyrics that started it going really well. You can guess which verse Stephen wrote: “Horror grips us...” [laughs]

A kid from the Midwest showed me that tuning that, from low to high, goes E B D G A D, and I got “Guinnevere” and “Déjà Vu” out of it.

David Crosby

That’s in standard tuning, but you were into alternates, as evidenced by the haunting sound on “Guinnevere.” How did you arrive at that unique tuning?

A kid from the Midwest showed me that tuning that, from low to high, goes E B D G A D, and I got “Guinnevere” and “Déjà Vu” out of it. I’ll tell you what got me started: My brother turned me on to jazz early on and I liked some keyboard players, including Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner. They’d play chords that were like huge freaking tone clusters. Thick stuff. My hand wasn’t good enough to play them in standard tuning.

Some guitar players can approach playing the same stuff as a piano player, using closed positions in standard tuning, but the guitarist can only produce six notes, so the piano player has got you by at least four. I couldn’t do it, but in alternate tunings, different inversions of the chords came up. I started to get to those strange, mystical places I wanted to go.

The chords on “Déjà Vu” can be found simply by barring the top three strings at the 3rd and 5th frets. It’s a matter of which order you pick the notes. I fingerpick with my thumb and first three fingers. The rhythm on “Guinnevere” goes 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2, which is actually very normal.

In alternate tunings, different inversions of the chords came up. I started to get to those strange, mystical places I wanted to go.

David Crosby

The main guitar is one of the 1969 D-45s. There are a couple of guitars along with it on the intro, and one of them is probably the 12-string. There are a couple of guitars on “Déjà Vu,” but I’m not sure which ones. We didn’t record it until the Déjà Vu album [released in 1970], but I had the music early on when I was leaving the Byrds and started hanging out with Stephen Stills.

The 50th anniversary edition of Déjà Vu includes the demos for “Almost Cut My Hair” and “Laughing,” which isn’t on that record but becomes a signature guitar track on your solo debut [If I Could Only Remember My Name, 1971]. Can you offer some guitar insights?

I’ll guess that I’m playing one of the ’69 D-45s on “Almost Cut My Hair.” That song is in standard tuning, although it might be dropped a whole step for the demo. “Laughing” is in an alternate tuning that, from low to high, goes D G D D A D, and again the demo might be dropped a whole step from the full studio version.

The vibe that tuning summons is similar to the slow section on “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” Did you get that from Stills, or did he get it from you?

More he got it from me. The people who taught me the most were Joni [Mitchell] and Michael Hedges. Stephen got into tunings pretty much right away, but he was a blues player, so he could take them to a different place than I could. Joni and Michael worked tunings to the most sophisticated level. They’re both geniuses at it.

And once I found out what kind of music I could write – “Guinnevere” being a good example – I loved it. So, of course, I kept exploring tunings. Over and over again, my best stuff is in alternate tunings.

“Music Is Love” [from If I Could Only Remember My Name] is another example, although I can’t remember that exact tuning right now [low to high, D A D G B D, and the original recording is dropped a half step]. That’s another good example of the original 12-string’s sound.

“I Think I” from the new album has a classic Crosby sound, perhaps in some kind of C tuning.

It’s in an alternate tuning that’s been very good for creating several songs, although I can’t say exactly what it is right now. There are two acoustic parts on there. Steve Postell played the beautiful acoustic lead at the end, and I played the fingerpicking part on one of the 1969 D-45s.

“Other Side of Midnight” is a lovely cosmic tune with a killer chord progression. What’s the guitar story?

You’re going to be pissed, because there isn’t one. Every single sound on that recording is synthesized. My son James played all the guitar sounds on a computer. He’s that good at it. You shouldn’t be able to do that, but he can. I’m not sure if we should allow him in the country. [laughs]

Who’s playing the high chimey intro on “Shot at Me”?

One of the best guitar players in the world, Dean Parks, wrote the music and played on that song. The lyrics are about guys coming back from the sandboxes in Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. It wrecks them and really screws them up.

Do you still take your vintage Martins on the road?

I’ve been taking two of the three ’69s, even though it’s crazy to do so because they’re worth, like, a hundred grand each. But I’ve been taking them on the road anyway because they’re that good. I also have a Gibson J-200 made out of Brazilian rosewood from their custom shop that I have taken on the road.

I’ve been taking two of the three ’69s, even though it’s crazy to do so because they’re worth, like, a hundred grand each. But I’ve been taking them on the road anyway because they’re that good.

David Crosby

And I have some guitars made by Roy McAlister up near Seattle. He showed up at my door one day saying he’d made me a guitar. It was a triple-0 body style, and I prefer dreadnoughts, but he mentioned that he was the guy at Santa Cruz Guitars who had made the copy of my 12-string, which is another one I have. So I invited him in, and it was one of the best guitars I’d ever touched. It’s still the one closest to the bed. I’ve given five of his guitars away to other players, and I have five others that he made, including a mind-boggling 12-string. I take four of his guitars on the road.

Including the 12-string?

No, when I play 12-string in the live show it’s an electric made by Alembic.

How do you electrify your acoustics?

We have gone through the stages of the cross when it comes to pickups. I don’t use any pedals. The signal goes straight to the house, and I have two monitors: one for my voice and one for my acoustic guitars. I use a Magnatone amp for the electrics. [John Gonzales reports that the acoustics all have D’Addario EXP16 strings and Fishman Matrix Infinity undersaddle piezo pickup systems that feed into Radial J48 direct boxes. The electric Alembic 12-string was custom built around 1970, and the Magnatone amp is a Twilighter.]

How are your hands?

I’ve got tendonitis in both. I can play, but I’m down to about 80 percent of what I used to be able to do, and it’s steadily deteriorating. The middle finger on my right hand doesn’t bend well. I had an operation done, but that actually made it worse.

I’m not trying to whine and snivel here. I’ve just got to cope with this reality. I’d guess I’ve got about another year to play guitar, if I’m lucky. It’s not a solvable problem. That’s just how it is. I’ve been playing for 70 years. I’ve had a good run, man.

I’d guess I’ve got about another year to play guitar, if I’m lucky.

David Crosby

Can you do any more tours?

I don’t think I can tour anymore. Well, maybe limited, but I do think I can make a couple more records. I’d like to do another Lighthouse record with Michael League and that lineup, but he lives in Spain now, so we’ll see.

James and I have already started the next record. They don’t pay us for them anymore, but we didn’t start doing them for money in the first place. We started doing them because we loved doing them, and we still love doing them. Albums are still our art form. They are what we have based our life on, and we still love making music. They are what we are going to leave behind.

Grab your copy of For Free here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

“I did the least commercial thing I could think of.” Ian Anderson explains how an old Dave Brubeck jazz tune inspired him to write Jethro Tull’s biggest hit

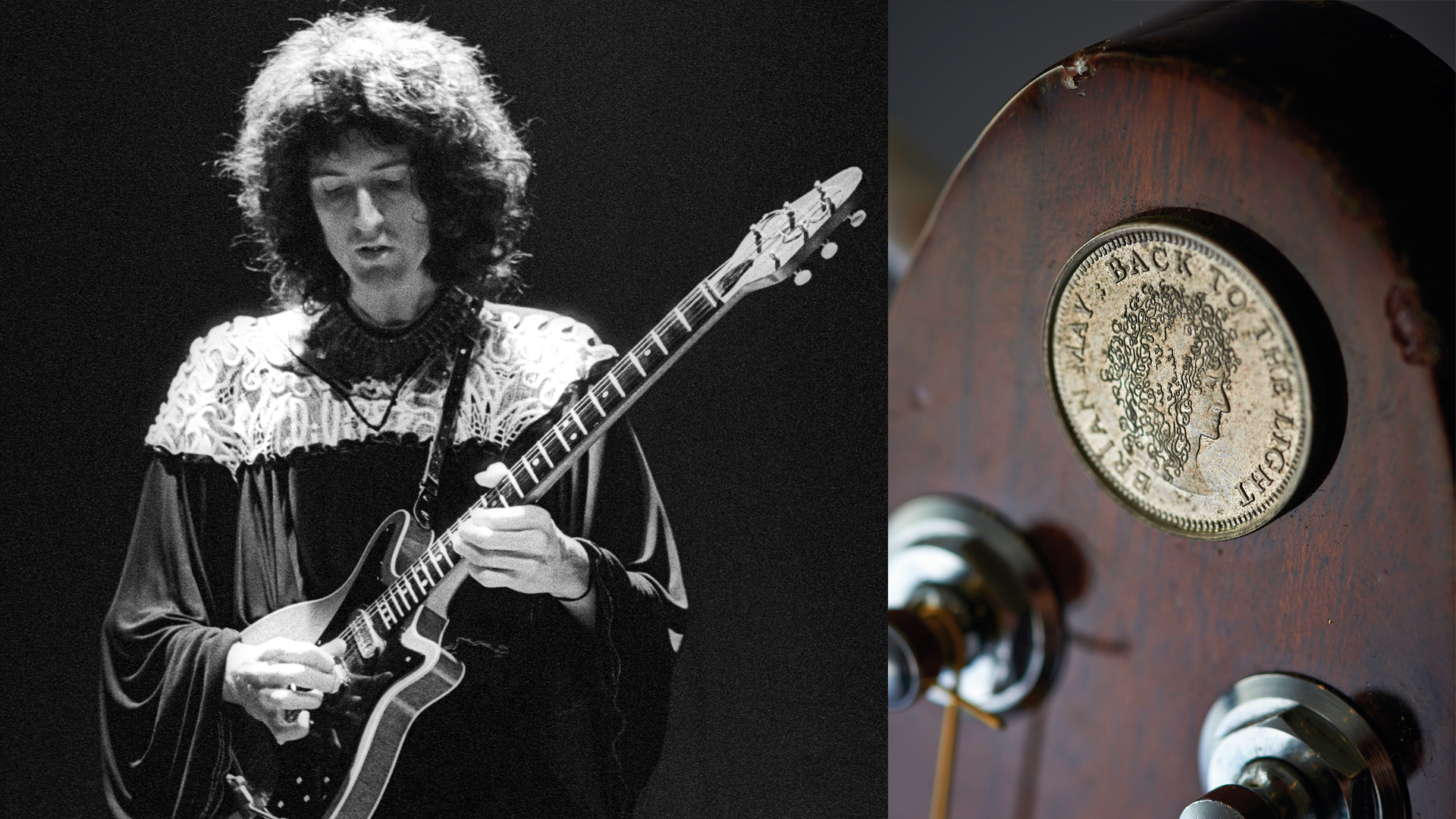

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone