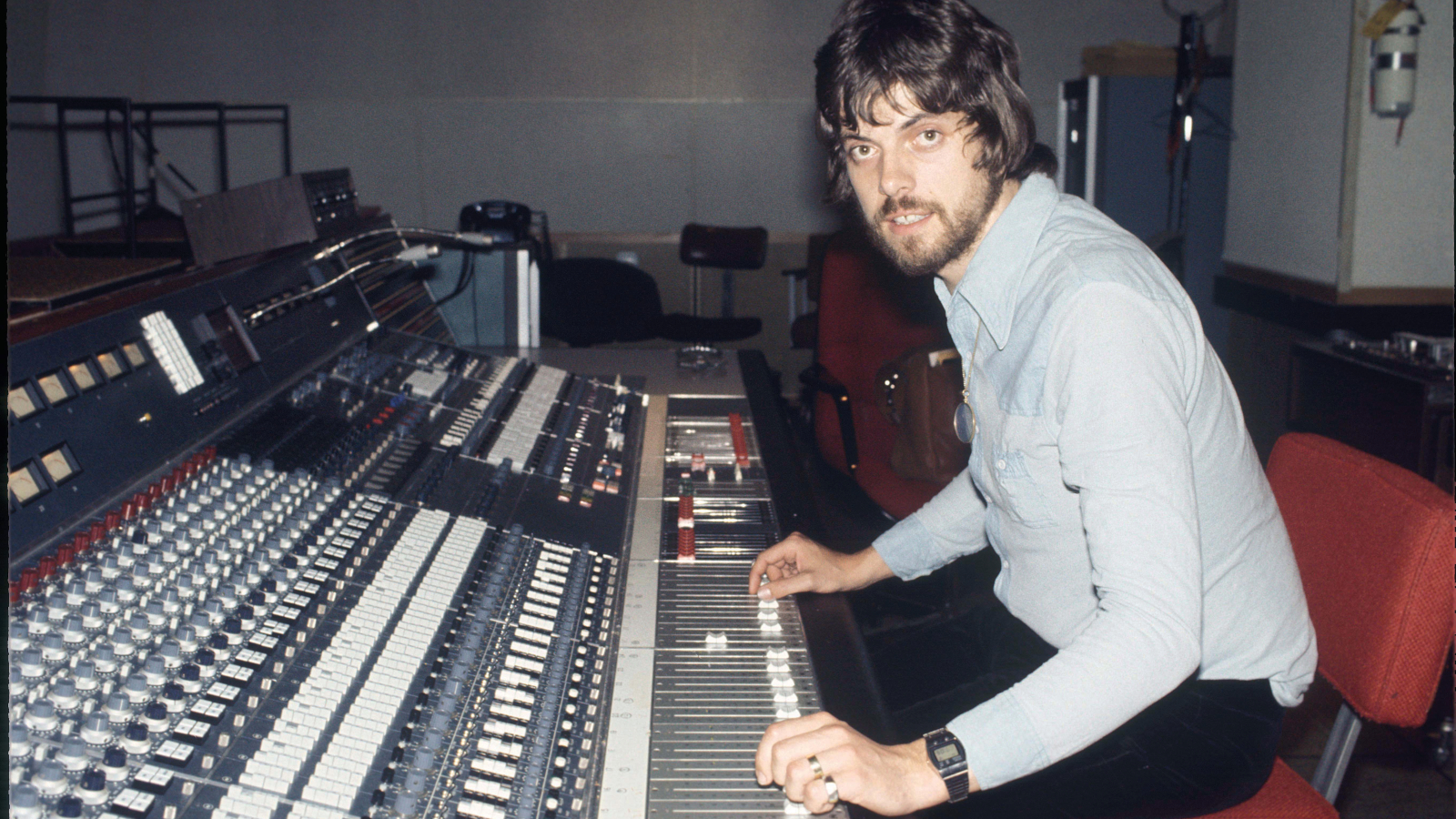

“Being an Engineer for Pink Floyd Was Arguably the Biggest Challenge I Ever Gave Myself”: Alan Parsons Takes Us Behind the Recording Sessions and Guitar Gear for ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’

“They’re so sound oriented; they used the studio to the absolute maximum,” says the ‘Dark Side’ engineer

One might establish the first “session” toward the making of The Dark Side of the Moon as the band meeting at Nick’s place, at which Roger’s idea of a continuous conceptual piece about things that “make people mad” was first sketched out. This was followed by Roger hiding away in his garden shed studio out back of his Islington home and creating a few demos of the material they had collectively begun writing. Next came working on the material through 12 days of rehearsals at Decca Studios in West London, followed by the live-show rehearsals at the Rolling Stones’ 47 Bermondsey Street warehouse and then, innovatively, the touring of the “Eclipse” suite.

Inextricably linked with EMI, Abbey Road Studios had at times been state of the art and sometimes not. Pink Floyd had recorded there regularly over the years (although not exclusively), with the most significant recent visits being for 1970’s Atom Heart Mother and portions of 1971’s Meddle. Significantly, the band felt they had to move on from Abbey Road to finish “Echoes” (comprising all of side two of Meddle) because, at the time, it was limited to eight-track recording. Nearby, both AIR and Morgan had 16-track facilities, which Abbey Road acquired in time for Dark Side.

For a mixing board, Abbey Road now had an EMI TG12345, its first solid-state, replacing the REDD .51, which was vacuum-tube based. The new console featured 24 microphone inputs and eight tape outputs, which came in handy, given the complexity of the sound effects the guys wanted on the album. Alan Parsons, engineer on the project, is emphatic, however, that the making of the record was essentially a 16-track production (“24 channels into 16 groups”), with many of the tracks being second generation because the band had run out of tracking room and had to consolidate and bounce first-generation tracks (the “Money” loop alone took up four tracks). The mix was conducted off the second-generation recordings, i.e. second-generation basic/backing tracks plus overdubs.

As Parsons told me, “Being an engineer for Pink Floyd was arguably the biggest challenge I ever gave myself. They’re so sound oriented; they used the studio to the absolute maximum. So it was a big challenge as an engineer. But I think I learned a bit, and I think they learned from me as well. It was a really good team effort overall.”

Asked about his Abbey Road employers George Martin and Geoff Emerick, Parsons says, “They were both mentors to me. George, I consider that probably, to a certain extent, I modeled myself on him because he commanded enormous respect from every artist he worked with and he respected them, and so that’s why he was the perfect inspiration.”

Of course, Abbey Road had essentially served as headquarters for the Beatles. Floyd would return there for work on Wish You Were Here and portions of The Final Cut and The Division Bell. The two Syd Barrett albums – 1967’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets – were cobbled together there, and Roger as a solo artist would use the facility as well.

Work on The Dark Side of the Moon began at Studio 3 on June 1, 1972, after the band had returned from dates in West Germany and the Netherlands, the culmination of about 40 shows playing the whole album live. Typically the band worked from 2:30 in the afternoon until midnight. The first song worked on was “Us and Them,” with the band sticking with Studio 3 for three days. Parsons had worked with the Beatles by this point but had also served as assistant tape operator on Atom Heart Mother, so he knew the guys well.

Work then shifted to Studio 2, from June 6 to 10, where the basic tracks for “Money” were recorded on June 7 and “Time” the following day (Gilmour’s use of a Kepex processor for tremolo can be heard on “Money”). [Made by Allison Research, the Kepex was a compressor/expander that could be triggered by an external source. Gilmour reportedly used a sine wave from the band’s EMS Synthi AKS synthesizer to trigger the Kepex and create an amplitude-modulated effect.] Roger had originally captured the sound effects for “Money” by recording on a Revox A77 the sounds of coins and other items tossed into a mixing bowl in his wife’s pottery studio and then splicing tape the old-fashioned way, working with the song’s 7/8 time signature. But this got re-recorded in the studio, given the possibility of improving it for the planned quadraphonic mix. One can hear a cash register (from a sound library record), an adding machine (Alan’s contribution) and paper tearing. Nick recalls drilling holes in old pennies and threading them onto strings to help create the innovative sonic symphony.

After two days off, it was back to work again at the same locale, June 13 to 17, followed by a move back to Studio 3, June 20 through 25, where the basic tracks were recorded for “The Great Gig in the Sky” on the final day.

David used his black 1969 Fender Stratocaster, which he later modified many times

Besides the new mixing board, also crucial to the process was the cutting-edge EMS Synthi AKS synthesizer, which allowed the band to create loops of sequenced notes, most famously for “On the Run,” where Gilmour and Waters collaborated on the effect. This was also used for the solo on “Any Colour You Like.”

As for Waters’ and Gilmour’s individual tools of the trade, Roger’s weapon of choice was the Fender Precision bass he’d been using since 1970, modified at this point with a maple neck by Charvel and Kluson tuning machines. David used his black 1969 Fender Stratocaster, which he later modified many times, soon with an additional switch that allowed him to manipulate the pickups to evoke the sound of a Fender Jazzmaster, and then with a Gibson PAF humbucker in time for the shows with Roland Petit’s Ballets de Marseille in early 1973. Also, notably on “Money” (and probably “Brain Damage,” “Us and Them,” and “Eclipse”), Gilmour played a 1970 mahogany-body custom Bill Lewis guitar with 24 frets. On “Money” this was used specifically to get the high notes in the third part of his solo. On “Breathe” and “Great Gig in the Sky” you can hear a Fender 1000 twin-neck pedal steel.

For effects, Gilmour used a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face (BC108), a Colorsound Power Boost, a Univox Uni-Vibe, a Binson Echorec 2 and PE 603, the aforementioned Kepex processor, and the EMS Synthi Hi-Fli guitar effects processor, which was a prototype version Gilmour bought from the manufacturer in 1972 at great expense. But effects were minimal, given there was nothing digital out at the time. Parsons indicates that most of his sounds were coming right out of the cabinets, augmented perhaps with a plate reverb or tape delay.

In the amp department, Gilmour used Hiwatt DR103 Custom 100-watt heads, a Fender Twin Reverb silverface 2x12 combo, a Maestro Rover rotary speaker, a Leslie rotary speaker cabinet (plus effects simulating Leslies), and WEM Super Starfinder 200 cabinets, which Parsons mic’d with Neumann U87s or U86s placed a foot in front of the cabinets. The classic Leslie rotary speaker effect can be heard on “Breathe.”

Concerning the legendary cacophony of alarm clocks on “Time,” that was something that Parsons had previously put together for a quadraphonic test record for EMI, recording each clock separately in an antiques shop in Hampstead. Quad was being touted at the time as the next evolution beyond stereo, and Parsons and Pink Floyd were ready participants – Atom Heart Mother, Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here would all come out on quad. Parsons took a portable tape machine to the shop and had to have the proprietor stop all the clocks so Parsons could capture them one at a time. Also on the effects front, explained Alan, “the footsteps on the intro to ‘On the Run,’ that was me and my assistant engineer, Pete James, pacing the floor at Number Two studio at Abbey Road.”

After some time off (but also more shows), there were further Dark Side sessions on October 10 through 12 and 17, 1972, followed by a show at Wembley Empire Pool on October 21. Work resumed October 25 to 27, but then the band was sent back on the road in mainland Europe in November. Work would often be interrupted to watch Monty Python’s Flying Circus, or to allow Roger to cheer on his beloved Arsenal FC. Parsons has said that he’d stay behind and keep working during the breaks for Monty Python, recalling that this is when he’d get some of his best ideas down on tape.

Work on 'The Dark Side of the Moon' began at Studio 3 on June 1, 1972

Rehearsals in advance of the final recording sessions took place January 9, 1973, with the band recording sporadically over two weeks beginning January 18 in Studio 2 before moving permanently to Studio 3. At this point the band recorded “Brain Damage,” “Eclipse,” “Any Colour You Like,” and “On the Run,” plus overdubs needed for the basic tracks from earlier sessions. Mason recalls that “Any Colour You Like” was a two-chord jam cooked up on the spot to fill space, with the highlight being Gilmour’s guitar solo. Dick Parry’s sax parts were recorded for “Money” and “Us and Them” (using a 1969 Henri Selmer tenor sax) plus four female backing vocalists – Doris Troy, Lesley Duncan, Liza Strike, and Barry St. John – were brought in to sing on “Brain Damage,” “Eclipse” and “Time.” Their voices were fed through a pitch shifter to achieve a sweeping effect. Of note, also on the vocal front, Parsons double-tracked most of the lead vocals, adding effects like reverb and delay.

Clare Torry’s vocals for “The Great Gig in the Sky” were recorded on January 21, with the sessions wrapping up February 1. Noted Parsons, “I suggested calling up Clare Torry to sing ‘Great Gig in the Sky’– they were unacquainted with her. There were a few specific instances like that where I injected some ideas.”

Torry did three or four takes, with Parsons indicating that the final performance was a composite. Torry remembers fondly the excellent mix Parsons got between her voice and the music in her headphones and greatly enjoyed closing her eyes and belting it out. Torry also recalls that the guys (other than Dave) looked completely bored during the process and she was ushered out quickly after she was done, feeling that she probably was not going to make the record.

At the end of the process, producer Chris Thomas was brought in to check out the final mixes. He recalls picking up the task at midnight and then driving over to AIR to work until 5 a.m. on Grand Hotel, his third of what would be four records in a row for Procol Harum.

Although he doesn’t admit to any disputes, apparently there was vehement disagreement about the final mix, with Roger and Nick wanting a drier sound emphasizing the sound effects and David and Rick wanting more echo, emphasizing the songs and melodies. Thomas was called in as mediator; both David and Rick would hover over him at different times, willing the faders to move their way, to the point where both ended up in the control room with him (Gilmour says he got his way). Parsons wasn’t happy with Thomas’s propensity to “limit” the drums, and later regretted that the drum sound could have been better.

Notably, Thomas was also at the Clare Torry session on “The Great Gig in the Sky,” and proved instrumental in synchronizing the echo on “Us and Them.” Parsons recalled that Chris had rode him hard to locate the “magic” rough mixes for the Rototoms used at the beginning of “Time,” but they were unsuccessful in their search. In the final analysis however, after three weeks of work, all parties were more than pleased with The Dark Side of the Moon. All that was left was to tour a record that actually existed.

Excerpted from Pink Floyd and The Dark Side of the Moon: 50 Years, by Martin Popoff (Motorbooks, 2023, $50). Copyright 2023 Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc. Used by permission.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song

"When they left town, I went to the airport and got to meet Ritchie, and he thanked me for covering for him." Christopher Cross recalls filling in for a sick Ritchie Blackmore on Deep Purple's first-ever show in the U.S.