Even before he released All Your Life, his 2014 tribute to the Beatles’ music, Al Di Meola knew that a sequel was mandatory.

“Let’s face it: Their catalog is so vast and incredible,” he says. “The first Beatles record I did was like scratching the surface. You record one song and you immediately think of three more you could do.

“So the idea of doing another one appealed to me from a conceptual standpoint, but when All Your Life became a big seller, it became a no-brainer. This is music that I love, and people all over the world want to hear it. The Beatles just make you feel good.”

Like All Your Life, the new album, Across the Universe (earMUSIC), sees the guitar legend re-imagining the music of the Fab Four in ways that are both startling and exhilarating.

“Here Comes the Sun” becomes a multiple–time signature acoustic and electric guitar orchestra, while “Dear Prudence” floats atop a soft bed of Caribbean percussion, over which Di Meola layers bewitching, lightning-fast arpeggios.

The sound that made me love the Beatles as a kid is the same feeling I have for them now. In fact, it’s deeper. How many things can you say that about?

A straightforward pop ditty like “Your Mother Should Know” is now transformed into a blissed-out, Latin-tinged epic of interwoven nylon-strings. The guitarist also basks in the riches of Abbey Road with the “Golden Slumbers Medley,” lacing “Golden Slumbers” with fluid flamenco licks before digging in for some searing rock on “Carry That Weight.”

“Doing straight-up covers is the easy way out,” says Di Meola, who admits that a fair amount of trial and error goes into such daring musical alchemy. “In many ways, doing something like this is harder than making my own records because I’m going up against the critics.

“If it were my music and they had never heard it before, they couldn’t say, ‘Oh, he screwed that part up,’ or ‘I liked the originals better.’ But the Beatles are sacred ground. So yeah, there’s a lot of second guessing. At the end of the day, it’s all about vibe. The vibe to each piece has to be right, and then I’m home free.”

Although he’s revered as a master in the annals of progressive rock, jazz and world music, Di Meola has never lost his affinity for the band he fell in love with at the age of nine, when he first heard his older sister spinning Meet the Beatles. And he can’t understand why some of his virtuoso contemporaries don’t hold the group in the same regard.

“I’m left with the feeling that a lot of jazz and fusion guys have kind of forgotten about melody,” he says. “It’s like melody isn’t as important as getting to your solo. With the Beatles, you have all the elements of what makes music great. There’s beautiful melodies and well-constructed harmonies. Each track of theirs is a lesson in song structure. They were so ahead of their time.”

He thinks, then adds, “The sound that made me love them as a kid is the same feeling I have for them now. In fact, it’s deeper. How many things can you say that about?”

Isn’t it remarkable that the Beatles wrote all of this music without understanding theory?

Very. But they had this inner kind of knowledge. A street sense. They had great ears and they learned everything on their own. It’s astonishing what they wrote without any kind of initial formal training. I know that Paul’s father played piano, so perhaps he got some amount of private lessons from his dad.

But for the most part, they were self-taught. They played American rock and roll - Elvis, Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers - and they honed their craft in clubs for years. Way before we heard of them, they had it down.

Have you been impressed by any previous Beatles covers released by other artists?

No, not really. I heard a lot of covers that really were awful, especially if they sing. I mean, I understand why people do it - it’s why I do it. But too many people just do the same thing. I wanted to do my own thing.

I didn’t want any of this music to sound the same as the original. I just wanted to do it in a new way

The production on this album is fuller than on All Your Life. Did the songs that you chose impact that decision?

Pretty much. I just wanted to do something more elaborate. I mean, there are some pieces that don’t lend themselves to my kind of treatment or style. What do you do with something like “Come Together”? It’s mostly one chord.

I need something with a lot of harmonic movement, meaning chords, beautiful melody. It has to be able to stand on its own. Now, maybe you want to syncopate the rhythm. Maybe you want to change a 4/4 feel into a 3/4, or a 3/4 into a 4/4. But at the same time, you don’t want to displace the melodies too much.

On the previous album, you seemed to favor Paul’s songs, but Across the Universe is split equally between him and John, with a little George and Ringo thrown in.

I think it was accidental. I didn’t look at the list and count who wrote which song. It’s funny - doing this, I open myself up to getting attacked. I read comments online, and I’ll see 20 really good responses, but there will be one person who’ll say, “I prefer ‘Yesterday’ being not so busy.” What is he talking about? It’s so not busy. I’m playing the melody, and what’s underneath isn’t busy. I can never figure out some of these comments.

“Dear Prudence” feels like it’s less married to the original song’s melody. It’s more abstract.

I guess so. I think the arpeggiated parts are definitely different than the original. They’re pretty interesting, I think. The melody’s in there - you’ve got to kind of hear that more than once or twice. But I didn’t want any of this music to sound the same as the original. I just wanted to do it in a new way.

You really opened up “Norwegian Wood.” It almost feels like a departure point for your own music.

I should have put a disclaimer in there: “You’re going to go on a much longer journey through Norway.” The original is pretty short. If you take out the voice and the lyrics, you’re left with two minutes of music. So I felt compelled to write some original music to extend the piece as an instrumental. This one is an extreme case of me adding almost an Al Di Meola movement.

I struggled with doing 'Yesterday' and 'Hey Jude' because they’re obvious, too. 'Till There Was You' felt good because it’s left-field. I like that

Are you playing an actual sitar on it?

The sitar sound is this device I’m using on my guitar. It’s a little box - I forget who makes it - and it says “sitar” on it. I just plugged into it and said, “That sounds cool. Let’s use it.” The song also has an Indian tabla player on it. I used him on “Norwegian Wood” and “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

How did you distill all of the different chords, the melody and textures on “Strawberry Fields Forever” so that you can play them as one guitar part?

It might sound like one, but there’s a couple of them. I just go by feel. I never looked at it like it had more than one texture. It’s chord melody again. On that one I used my Ovation steel-string, which I haven’t played so much in past years, and I had some effects come in at times. I blended sounds on this VG-88 Roland synth module.

You do a lovely version of “Till There Was You,” which the Beatles didn’t actually write.

They didn’t, but they did such a beautiful version of it and made it their own. I remember that from Meet the Beatles and when they played The Ed Sullivan Show. I got the music and I was surprised at the complexity of the chords. There’s augmented, there’s diminished... There’s all kinds of jazz chords in it.

In the middle, you turned it into a briskly picked rock number.

If I had played it the way they did it, it would be a bit old-fashioned. I wanted to make it a little hipper, so that’s what I came up with. Listen to the chord changes. I’m playing a rhythm that’s very unorthodox in a way. It’s more percussive than theirs.

I’m also playing a Rickenbacker bass like Paul played - same bass, same gauge flatwound strings

A lot of guitarists would wonder why you still haven’t recorded “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

And there’s an answer to that: Because it’s obvious. Come on, it’s so obvious! I wanted to avoid that. I struggled with doing “Yesterday” and “Hey Jude” because they’re obvious, too. “Till There Was You” felt good because it’s left-field. I like that.

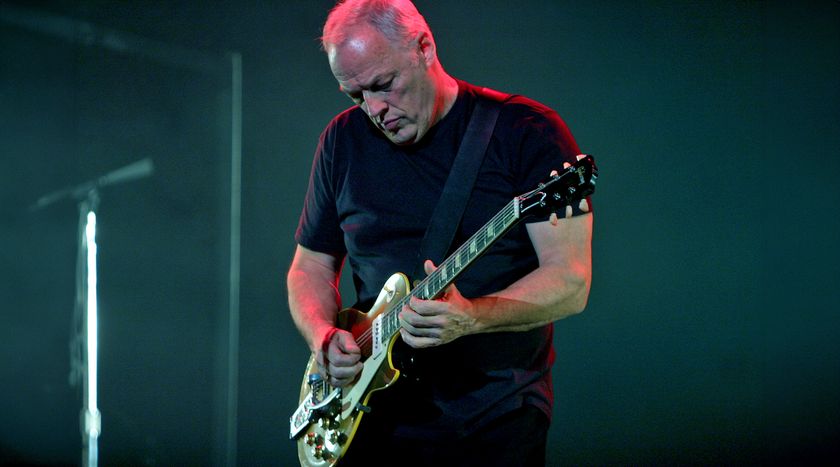

In terms of guitars and amps, what did you use for the record?

Always the Conde Hermanos. It’s my signature-model nylon guitar made in Madrid. But on “Here, There and Everywhere,” I used a smaller-scale full body, this very old Conde that I found in a music shop in Germany.

I also played an Ovation a lot, a 12-string Guild and a Martin D-18. On “Here Comes the Sun,” I played a 12-string mandolin; I don’t know its name - I got it in Nashville.

For electrics, I played my PRS signature Prism and my ’71 Les Paul Custom. I haven’t used the Les Paul since the ’70s - it weighs a ton. But man, it’s so punchy. It hits you right in the chest. I haven’t been able to get that sound with any other guitar through any amp.

It’s funny, though: My engineer and I were trying to find a Marshall to use with the Les Paul. We went looking through stacks of stuff in my garage, and way in the back of everything we found a 50-watt from the mid ’70s. I didn’t think it would even work, but I plugged it in and it fired right up. It was like, “Whoa! What a nice sound!”

Oh, and I’m also playing a Rickenbacker bass like Paul played - same bass, same gauge flatwound strings.

I have a friend in Long Island who is a Beatles authority. I called him up and I said, “Can you get hold of a Rickenbacker?” And he said, “I can get one for you.” He knew of someone, and we got it on loan for the record. You plug that thing in, and it’s like, “There we go. That’s the Paul sound!”

- Al Di Meola's Across the Universe is out now via EARMUSIC.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

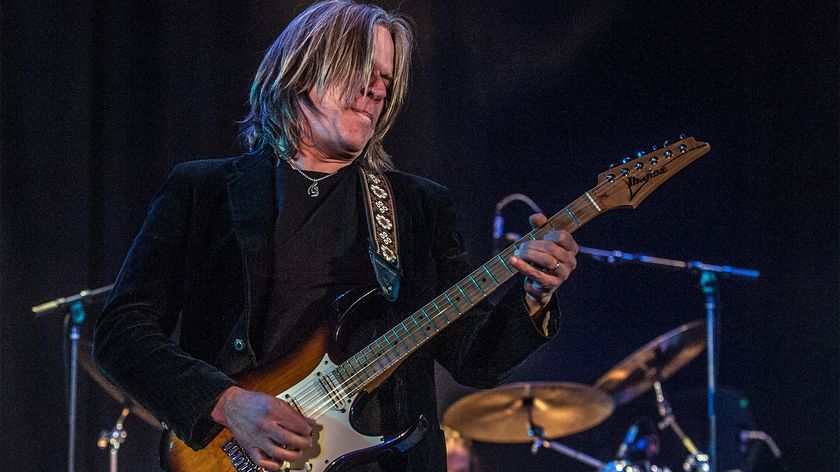

“I thought, Robert Fripp’s a good guitarist. Maybe we could do something.” Andy Summers isn’t a fan of King Crimson, but his collaboration with Fripp came along at just the right time

"I don’t like collector's items. I said, ‘Give me the blue one.’" Chrissie Hynde reveals the origins of the 1965 Fender Telecaster she's played since the dawn of the 1980s