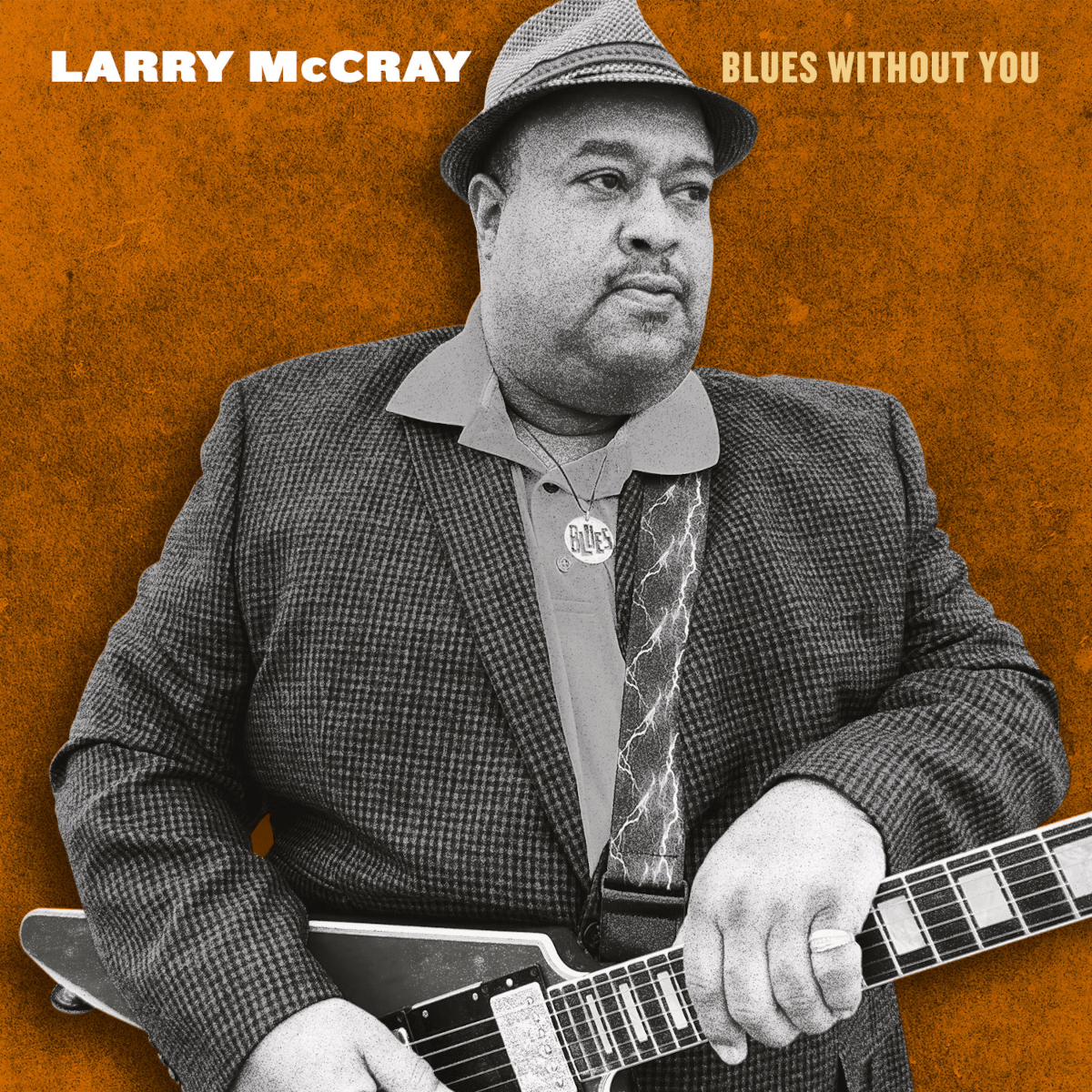

After 20 Years in the Wilderness, Larry McCray Returns in Style With 'Blues Without You'

Thanks to a restart and a new album his future looks brighter than ever.

Larry McCray’s new album, Blues Without You, is his first record of original material since 2007. McCray burst onto the scene as a major new voice in blues guitar way back in 1991, with the release of his debut album, Ambition, followed two years later by Delta Hurricane.

It looked like he was destined for the sort of mainstream crossover appeal enjoyed by the likes of Robert Cray and Stevie Ray Vaughan, but his blues train started to derail.

By 2001, without a record deal, McCray was releasing his music on his own label. He’d resigned himself to the possibility that his major-label days were behind him, when Joe Bonamassa called to ask if he’d record for Bonamasssa’s label, KTBA (Keeping the Blues Alive).

The result is Blues Without You, not only McCray’s career-best record but also one of the strongest blues guitar albums released for many years. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that there will be a better blues record released in 2022.

McCray presents the same kind of two-fisted combo that made giants like B.B. and Freddie King such formidable artists, with not only the ability to play blisteringly effective solos but also a voice that can rival the best blues singers from any bygone age.

McCray’s soloing is both fluid and visceral; he is unafraid to hang on to a couple of notes until every last drop of emotion and soul has been wrung from them.

The release of Blues Without You will be accompanied by a documentary that reveals the ins-and-outs of McCray’s hookup with Bonamassa, and shows both men and co-producer Josh Smith working out ideas for the record.

The film also demonstrates that McCray’s stalling career was in part due to poor management from his former manager, Paul Coch, who died in 2021 in a car accident.

It makes for compelling viewing and reveals McCray to be a deeply humble, emotional man who truly appreciates getting a second bite of the cherry.

It must feel good to be back on a label that has prominence in the industry.

Yes, absolutely. Sometimes, when things don’t work out, you have to make peace with yourself. That’s what I was doing, and then the opportunity just kind of fell into my lap. I am very pleased with how the record turned out. It’s my best album by far.

In the documentary, you use an acoustic guitar to perform many of the songs that subsequently turned up on the album in electrified form. They were such strong performances. Was there ever any thought of recording them that way?

I’ve been trying to get that done for the last 25 years, and I couldn’t. I’ve never been one to use race as an excuse for what you can’t achieve. I don’t know if my image wasn’t palatable to the people who make these decisions, who had the control, or if they just weren’t interested in my brand of music. But with that said, there was never a plan to make this anything but an electric guitar album.

Watching the documentary, you seem very humble about your own talents. Do you think perhaps the way that your career became derailed undermined your sense of where you should be in terms of recognition?

I guess it’s not really that important what I think about my music; it’s what the people think. I’ve spent over 40 years making music, and if somebody wanted to give me an opportunity, it’s not like I sat on my ass and didn’t work for it. I’ve played every honky-tonk and every dive.

I’ve played some high places and some low places, and a lot in-between

Larry McCray

I’ve played some high places and some low places, and a lot in-between. If the powers that be don’t accept what you do, there are some doors that you can’t open yourself. I put albums out on my own label, and I worked constantly, but I never had the means to promote them properly.

There are some parallels with you and your label mate Eric Gales, in that you both lost your way career-wise for some time, and now you’ve both just released career-best albums on KTBA.

I knew Eric at the start of his career. We’ve been friends since the late ’80s. Eric was always my go-to when anybody was talking about who was a great blues guitarist.

He was such a talent even then; I knew him when he was just a kid. He used to come out to my house and we’d sit up late playing guitar. He’d play guitar and I’d listen. [laughs]

I’m a non-political and a non-controversial person, but when you look at it straight on, I wonder how people could justify why someone like Eric or me couldn’t get opportunities in the music business.

I think, fundamentally, sometimes people can get judged by two different standards. I’ve been away from the game too long to just make that a focus, but I know I worked my ass off to do everything that I could.

Blues Without You is a very organic, timeless album. Was that a deliberate attempt to re-create the warmth of those classic blues albums from the early 1970s that B.B. and Albert cut?

I don’t have to try, because that’s who I am. I’m just being myself. When I look back on my career, that’s what I’ve always been, and I guess that’s just how it comes out. [laughs]

I’m just being myself. When I look back on my career, that’s what I’ve always been

Larry McCray

It seems like there are a lot of church and gospel influences in your vocals. Was that something you grew up with?

No. I was raised around that, but I was raised differently. I was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, so I didn’t get the chance to pursue that gospel side of music. My parents converted to that when I was about six years old. I did hear that music, and it had an influence on me, for sure.

You are the kind of singer who sounds like they’re living every word that they say, so presumably the lyrics of a song are very important to you.

I sing about life. And I sing about it in a way that everyone can relate to, whether it’s being sick, not having money, relationship problems or whatever it might be. I feel every word that I’m singing.

I feel every word that I’m singing

Larry McCray

We all need to feel whole, and I hope that’s what my music helps people to achieve. I call my music “good-time, feel-good music.” I don’t want to be technical or nothing, trying to win the respect of people who care about those things; I want to win the hearts and souls of people – what people feel in their heart.

You always have great phrasing on your solos and fills. A prime example of this is your playing on “Without Love It Doesn’t Matter,” where you leave gaps between phrases, almost as if to allow the listener time to digest what you just played.

Exactly, that’s right. It isn’t necessary to play any more than that. Whenever I play something on my guitar, I try to channel what I call the four greats: B.B., Freddie and Albert King, and Albert Collins.

I try to channel what I call the four greats: B.B., Freddie and Albert King, and Albert Collins

Larry McCray

I think of Albert Collins as the razor. He slashed, cut and sliced with his guitar. B.B. was class and elegance. Freddie was raw power with both his vocals and guitar. And Albert King played the crying, weeping guitar.

My playing draws from all those four guys every time I take a solo. If I want cut, elegance, power or a real weeping feel, I tap into one of those four guys.

“No More Crying” is such a great southern soul ballad with the same emotional resonance of Vince Gill’s “Go Rest High on That Mountain” and an ability to comfort someone dealing with loss.

I co-wrote that with a youngster that I influenced, Aaron Sarkar, who was 30 years my junior. We met at a B.B. King concert when he was working in hospitality there. He was 15 years old at the time, and I remember him saying that he wanted a musical career.

Fifteen years later, he came to my house and he was showing me some words that he’d written. He said they’d come to him and he wrote them down in about five minutes.

As soon as he read the words to me, I automatically had those chord changes. I just sang it exactly as it is, the first time I tried it. It just came in an instant. It was the easiest song I ever wrote.

The turnaround in your career is very much echoed by the sentiment behind “Don’t Put Your Dreams to Bed.”

Definitely. I wrote that with my girlfriend, Peggy Smith. We thought of that concept together. That was another song that was real easy to put together. I think a lot of the best songs do come very easily, as if they were just meant to be.

A lot of the best songs do come very easily, as if they were just meant to be

Larry McCray

It is interesting that the song “Blues Without You” was dedicated to your former manager, Paul Coch. Obviously you had plenty of good times together, but I know he also caused problems for your career at times.

Although we had a lot of rough roads and went through some tough things together, I certainly didn’t hate the man. We spent 34 years together, you know? He definitely did work very hard to try to help me get success, but he just didn’t have the right people skills.

For whatever reason, people sometimes found it hard to work with him. I know Joe had tried to contact me years ago to do this, but Paul didn’t tell me. That was just one of many incidents that happened over the years.

In some ways there wasn’t a whole lot that I could have done. Maybe I could have found another manager, but I couldn’t find someone else who was interested.

The closing track, “I Play the Blues,” is a solo acoustic and vocal piece, which is a great way to close the album, as a real contrast to what has gone before.

I did think that we were going to do it with the band, but Joe thought it would be nice to do the stripped-down acoustic guitar version. We did the whole album in seven days, and that was the last song that we recorded.

I did a lot of singing and playing in that week, and by that time my voice was starting to feel a little rough. Joe thought the slight rawness in my voice really worked for the song, although I do think that maybe I could have sung it better if I’d had a chance for my voice to recover slightly. But that’s all that I had left.

We did the whole album in seven days

Larry McCray

When it comes to playing solos, do you plan beforehand what you’ll do?

No, I never do. I always just play straight through without any preparation, in one pass or maybe two passes at the most. I do like to warm my chops up before I record, maybe for an hour or so.

What were you playing on the album?

I only took one guitar with me, a Les Paul Deluxe, as I was flying and I couldn’t really take any more than that. I used a lot of Joe’s guitars and amps.

Joe has so much great gear that there isn’t anything that I could have taken with me that would have been any better anyway. [laughs]

You’re very much a Gibson guy, although I believe way back you used to play a Strat.

That’s right. In fact I played an Ibanez before the Strat. What happened was that I went over to England, and I saw Gary Moore playing. When I heard his humbuckers, I thought, Okay, there’s a bigger bear in the woods; I need to keep up here. [laughs]

As soon as I got back to the States, I bought a tobacco-brown Flying V, which I played a lot. That was when I also discovered that I really liked Les Pauls as well, and the 335 came soon after that.

I’m determined that I’m going to make the most of every opportunity to make up for a lot of lost time

Larry McCray

I like to switch my tones a lot, even in the middle of a solo, where I’ll flip from one pickup to another. I know Albert King always did that. I think it takes the solo on more of a journey through different tonal ranges.

Things must be very busy for you now that the album is being released.

Yeah. I’m also doing some things with Devon Allman and the Allman Brothers Revue right now, and I’m starting to book a lot of dates for myself.

Everything is really starting to build up, and I’m determined that I’m going to make the most of every opportunity to make up for a lot of lost time.

Order Blues Without You here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song