“I went to high school with Tom Morello, and we had a band. When I joined, I was the best person in it, but when Tom went to college, he started practicing. When he came back, he was too good for me!”: Tool's Adam Jones on Silverbursts and “evil” tones

In this archival interview, Tool's reclusive guitarist discusses his preferred alternate tunings, defying convention, and how he consistently employs wah, without using it in an “obvious, '70s porno-movie way”

This interview was first published in the June 2001 issue of Guitar Player.

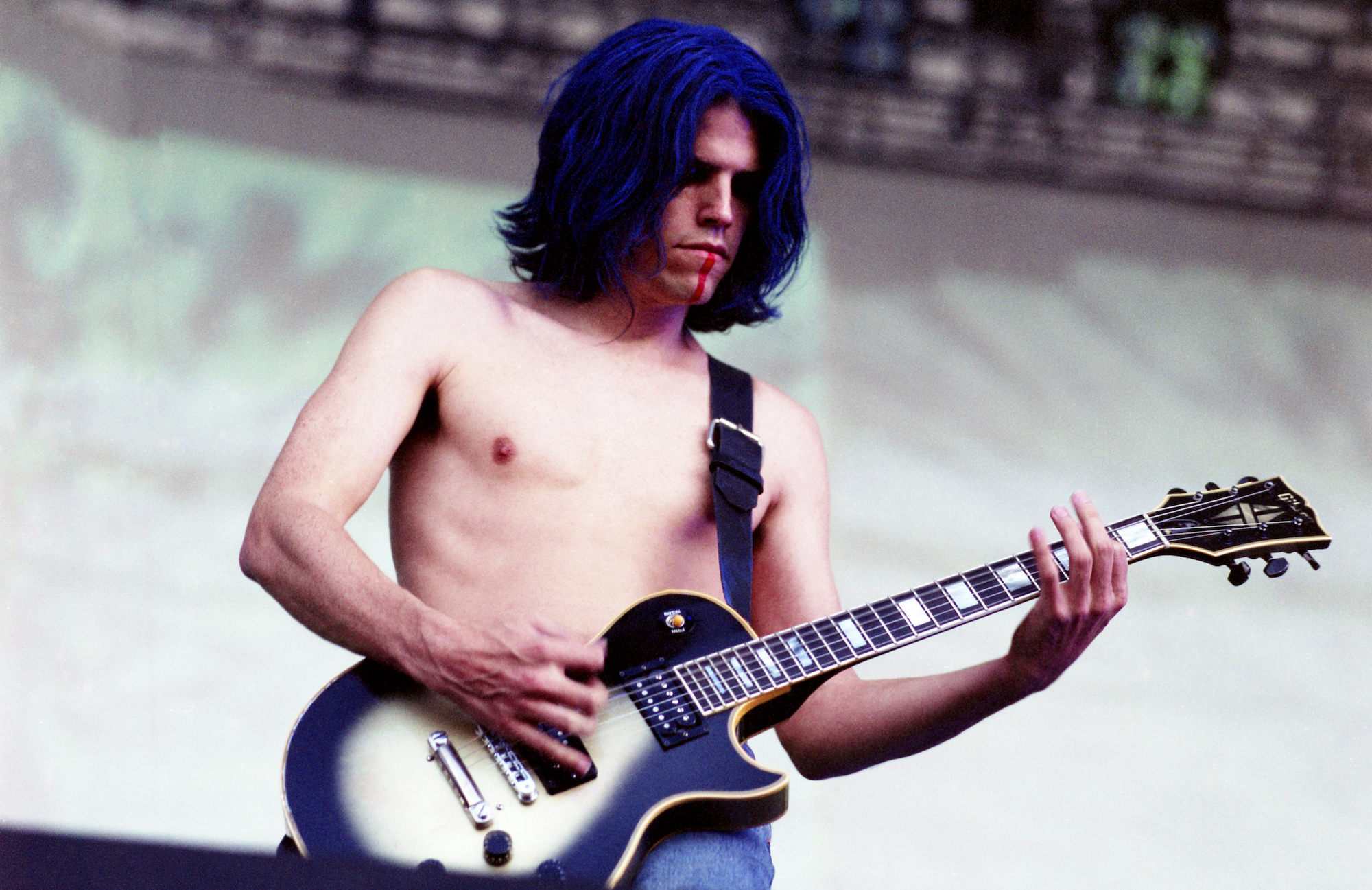

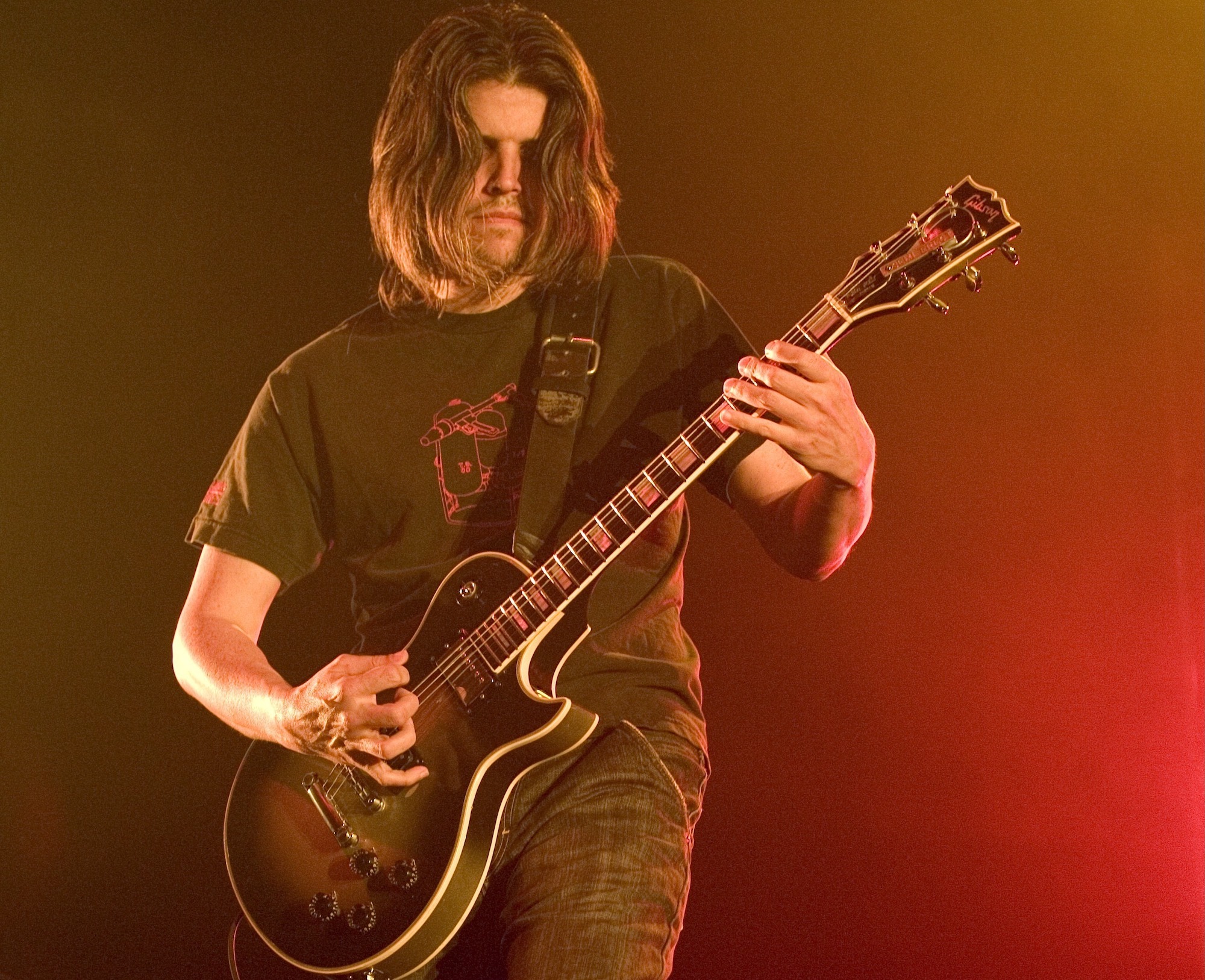

Historically, successful rock guitarists have often been larger-than-life celebrities. But for Tool guitarist Adam Jones, staying as unidentified as the Loch Ness Monster is not only welcome, it's part of his master plan. He and bandmates Maynard James Keenan (vocals), Danny Carey (drums), and Justin Chancellor (bass) have never appeared in any of their videos, they rarely grant interviews, and they frequently perform on stages so dimly lit that their faces are masked in shadows.

“We've gone to great lengths to stay pretty anonymous,” Jones admits one afternoon from the recreation room of Larrabee Studios in L.A., where Tool mixed their new album, Lateralus.

Jones isn't a shredder, a pop guitarist, a jazz man, an avant-garde iconoclast, or a blues player, but his performances often include elements from all those genres. His melodies are oblique, his riffs angular, and his passages unpredictable. He'll pluck a shimmering arpeggio one moment, segue into a droning mantra, and then tear into a distorted barrage of wailing chords.

Coming off a three-year hiatus (due to a legal battle with Tool's former record label), Lateralus shows Jones at his most dynamic and expressive as he conjures an array of bizarre licks and alluring tones. An exercise in concentration and tenacity, the album abounds with unconventional meters and abrupt rhythm shifts. None of the tracks are under six minutes, and most are over eight.

Tool were hugely influential to alt-metal bands such as Korn, Limp Bizkit, Deftones, Incubus, and Linkin Park, and if Lateralus is any indication, Jones and friends will likely be a shining beacon for the next frontier, as well.

Your playing is very striking. It's muscular at times, and delicate at others, but it's never catchy in a conventional pop sense. In fact, it's very hard to hum a Tool guitar part.

“I've never wanted to be a conventional guitarist in any way. When I started playing guitar, my heroes were all about riffs, not leads. Then I got into more experimental players, such as David Sylvian, Robert Fripp, and Steve Howe. But I also liked Devo and Brian Eno.

“At the time, it seemed like everyone else was playing lead guitar, and I just got sick of it. I never went down that path myself. You're right about my parts not being catchy, though. If I don't have a guitar when I'm talking to Maynard or Danny about a part, I'll try to hum it, and even I can't do it.”

I think visually when I play guitar. I look at each song as a little film

When do you come up with your best passages?

“The best guitar parts I write come from noodling. I'll sit at home watching TV with a guitar in my hands, and just start playing a riff over and over. It's weird. A lot of the stuff I do comes from blues scales.”

Yet nothing you play sounds like blues.

“Well, my stuff usually starts off as these 4/4 things based on traditional guitar riffs, and then they morph into something that's kind of way out there. But it's good to have a launching point to evolve from.”

When you were crafting parts for Lateralus, what were you striving to accomplish artistically?

“I think visually when I play guitar. I look at each song as a little film. I like to start with an opening shot, and then segue into different scenes. I like to drift off in the middle, go somewhere totally unexpected, and then have everything resolve itself in the end. It's a whole experimental journey.”

The visual and experimental aspects of your style often lead you to construct parts that don't sound like guitars.

“I just do what I do best, which is try to take Tool to the next level. I'm always thinking of something new I can add in. I like to do volume swells with delay to create ambient sounds. I'll scrape the strings of my guitar with various things, and I place electronic devices over the pickups to get weird sounds.”

What kind of electronic devices?

“I get a lot of cool sounds out of an Epilady. It uses a spinning wire – almost like a guitar string – to rip the hair off a woman's legs. I place it over the pickups and control the speed of the motor by keeping my thumb on the coil.

“I got the idea from Dave Navarro, who I once saw perform a solo with a vibrator when he was in Jane's Addiction. I thought that was so cool. And then I started listening to German industrial bands like Einsturzende Neubauten, who use crazy stuff on their instruments to take their sound to another place. So I'll buy a bunch of toys, rip the guts out, and use the motors to make some noises.”

You also use alternate tunings.

“I use drop-D because I like to have an evil tone, and I can get a lot of weird sounds and textures by simply moving my fingers around. After I had been playing drop-D for a while, I started doing drop-B, and then, on the song Parabola, I tried drop-B/E. It's normal 440 tuning, but the E string is dropped to B and the A string is dropped to E. It's even more evil-sounding than drop-D.”

How did you come across the drop-B/E tuning?

“We did Prison Sex [from the band's 1993 album, Undertow] in drop-B, and I just wondered how the E would sound next to the low B. That was a long time ago, before everyone got excited about 7-string guitars.”

Do you use any other tunings?

“I've tried DADGAD and tuning all the strings to the same note, but I always go back to the dropped tunings.”

Do you layer guitar parts to get such a huge sound?

“Not very much. There are a couple of songs on the album where I overdubbed a few layers, but for the most part, it's just one guitar. You see, I want to be able to pull off everything I do in the studio onstage. I usually do one pass routed through different amps, or two passes where I'm playing the exact same notes to make a part more powerful.

“I plug into three amps at the same time – even when I play live. For what I want, I don't think one amp would do the trick. One amp is for a solid-state sound, one for more of a non-master-volume tone, and the third fills in the bottom with a cardboard crunch.

“If you used the amps individually, you'd find that one doesn't have much low end, and one doesn't have enough high end. But they're really good together because you're getting three different things at once, and you can hear all of that in the sound. That's why it sounds so big.”

Making a Tool record is not like making Sgt. Pepper's. I'm comfortable with having the same sound live and in the studio

What kinds of amps are they?

“I use a modified non-master-volume Marshall bass head and a Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier, which I swapped out with a Sunn Beta Lead for the recording. But my favorite amp is a Diezel, which is a four-channel tube amp from Germany. It's awesome.”

Are you still using Gibsons?

“I have some Gibson silverburst Les Paul Customs – they made those guitars from '79 to '81 – and I dedicate one for the tuned-down songs. When we're recording, I'll use a Gibson SG if I want to play something softer.”

Do you switch between pickup settings very much?

“I do sometimes when we're recording, but live, I just use the treble pickup. I turn the other one off, then I can use my pickup selector to kill my guitar sound real quick. When I use the tone knob, I either turn it all the way up or all the way down, and I leave it that way.”

How about acoustic guitars?

“I used a Guild that I borrowed from a friend for a couple of things on the record, but when I'm playing with the band I usually want to feel the power of an electric guitar. If I want a softer tone, I'll just turn down or play with a lighter touch.”

What pedals are you using?

“I like to keep it really simple. I use an Ibanez digital delay and flanger, a Boss EQ pedal, and a Dunlop 535Q wah. I don't use the wah in an obvious, '70s porno-movie way. I use it for transitions and flavors – it's good for subtle changes in tone, and it's a big part of my sound. There's wah on nearly every song on the new record.”

Do you use the same setup live as in the studio?

“Making a Tool record is not like making Sgt. Pepper's. I'm comfortable with having the same sound live and in the studio. In fact, I'm not comfortable playing something that couldn't be easily reproduced onstage – even if it sounds great.

“I get the best takes when I'm just using my usual gear, because I'm more at ease. That's really important when you're totally under the microscope in the studio. Every little mistake matters, so you want to make yourself as comfortable as possible.”

When did you first pick up the guitar?

“We always had a guitar sitting in our house. My dad was self-taught, and he showed me some chords. Then my brother and I would jam together and make really bad music. Later on, I went to high school with Tom Morello, and we started a band together.”

What did you call yourself and what was that experience like?

“It was called the Electric Sheep. I played bass and he played guitar. When I joined the band, I was the best person in it because Tom had just started playing. But when Tom went away to college, he started practicing and practicing. When he came back, he blew me away. He was too good for me! [Laughs]”

Have you had any formal musical training?

“I played violin when I was a kid, and I can't tell you how many times someone tried to kick my ass while I was walking home from school. My violin case usually prevented my head from smacking really hard against the pavement! But I didn't let that stop me, because I really liked playing, and I had a good teacher. He played Monty Python music for me, and did these really absurd things. He made me appreciate that music could be serious and fun.

“One time, we had a recital for the parents, and just before we went on, he gave us all toy guns, and said, ‘Okay, at this particular point, I want you to stand up and start shooting at the other side of the orchestra.’ That kind of thing affected me a lot, and I think I brought that love for the bizarre into Tool.”

Tool have never compromised the length of a song just because we're concerned about what people want to hear. We just go with how we feel

Most of the songs on Lateralus are more than eight minutes long – which is unusual in today's marketplace of easily digestible pop. Do you ever worry about going on too long and losing your listeners?

“When I was a kid, I never thought once about whether a song was too long. Led Zeppelin, Yes, Pink Floyd and King Crimson did these huge, epic things, and when they were done, I always wanted to hear more.

“Tool have never compromised the length of a song just because we're concerned about what people want to hear. We just go with how we feel. That's why we won't do edits for radio – they corrupt the song. We're only concerned about getting from one place in the song to the next, and then to the end. At that point we ask, ‘Well, did it resolve itself or not?’”

How is writing an eight-minute epic different from writing a three-minute pop song?

“I don't think I could write a three-minute pop song! What we're doing isn't pop music. It's not the priority of this band to be radio-friendly. If it takes three minutes to express an idea, fine, but if it takes 20 minutes, then that's what it takes.

“It's about how a song feels. There's a lot of jamming involved when we compose, and a lot of scrutiny and tearing something apart and putting it back together. We explore as many paths as we can for a song, just so we know we've chosen all the right ways.”

When Tool formed in 1989, you were working in Hollywood as a special effects designer on films such as Predator, Edward Scissorhands, and Jurassic Park. How did you divide your time?

“I thought, ‘Here's my job working on special effects for movies, and here's my hobby playing guitar.’ I met Maynard through a friend of mine that he was dating, and we became good friends. He played me a tape of a joke band he was in back on the East Coast, and I went, ‘Maynard, you sing good!’ I kept bugging him to start a band on the side with me – just for fun.

“Danny lived downstairs from Maynard, and he didn't want to play with us. Then we had a practice session, and the guy who was supposed to drum for us didn't show up. So Danny felt sorry for us, and agreed to play. He said, ‘Well, I'll sit in on the sessions, but that's it.’ And he sat in and went, ‘Wow, we should jam again.’ We started rehearsing a couple of times a week, and pretty soon Tool became an actual band.”

When Zoo offered the band a record deal in 1991, you quit working in Hollywood to focus on the band. Was that a tough decision?

“It wasn't hard. Even though we all had steady jobs, when we got signed we said, ‘Okay, well let's give this a try.’ That's how I look at life. It's like you're surfing – you grab a wave and try to ride it as long as you can. And if you fall off, you can try to grab the same wave or go catch a different one.

“It was a little frustrating to have my parents going, ‘What are you thinking?’ But I loved music, and I wanted to give this an honest shot. I'm glad we did.”

Tool reached their peak in the late '90s at a time when bands such as Nirvana, Soundgarden and Alice in Chains were ruling the charts. Most of your former peers have broken up – how have Tool managed to stay together?

“Maybe because we don't take ourselves too seriously. When we started the band, I don't think any of us were saying, ‘We're going to work real hard and get signed.’ When we first got an offer, we all laughed and kind of blew it off. We've kept that attitude throughout. No one has allowed what we've done to go to his head, and everything we do still has a ring of comic relief to it. But beyond that, it's the respect we have for each other that makes it all worthwhile.

“The four of us click so well when we play. There's no real formula, it's just the chemistry of the whole band. And as long as we continue to enjoy playing together, we will. The minute that ends, Tool will end, as well.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Launched in 1967, Guitar Player was the world's first guitar magazine and is now one of the premier sources of guitar news, interviews, reviews and lessons. When a story is credited to 'GP Editors', it means it's coming from the magazine team itself and that more than one of us has worked on the story.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened