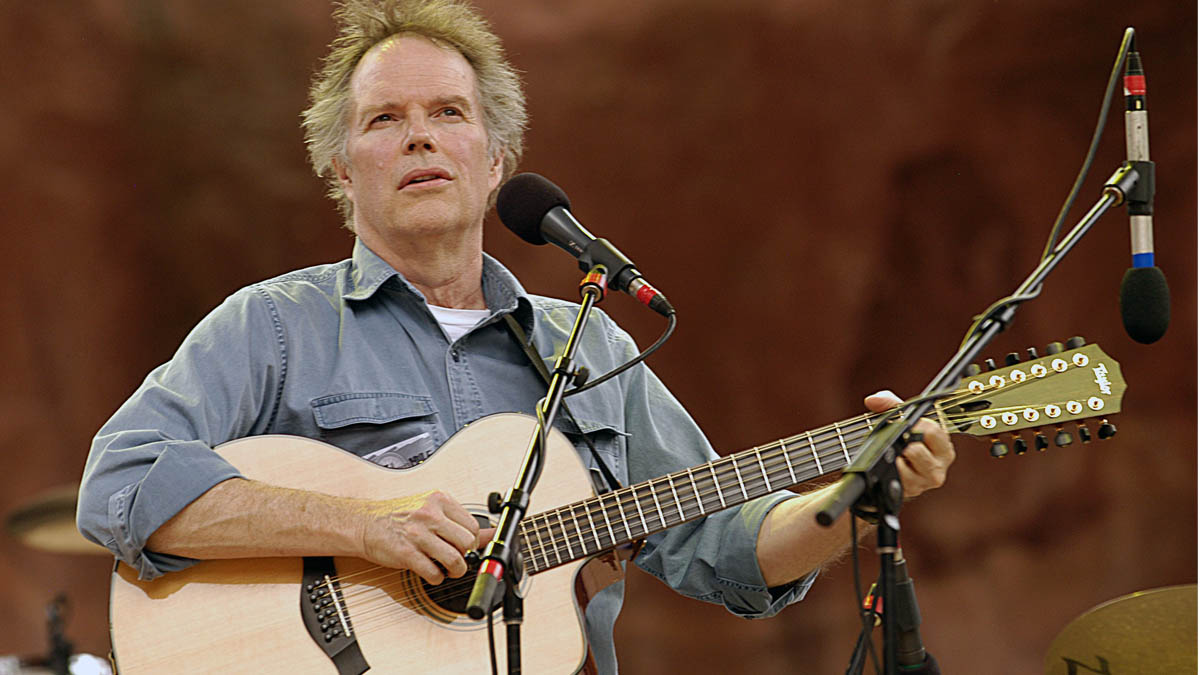

Acoustic Icon Leo Kottke on Miking, Reunions, and How to Play Well with Others

With bassist Mike Gordon rejoining him on new album 'Noon,' Kottke unpacks the writing and recording process.

What do you do for a third act when you’ve spent three decades as one of the planet’s most influential solo acoustic players, renowned for fingerpicking your signature Taylor 12-string jumbo with a thunderous tone in lowered tunings?

How about forming a duo with a jam-band bass player who not only thumps in the low end but also tends to meander melodically up into guitar territory? What seems unfathomable to most mortals makes perfect sense for musical mutants like guitarist Leo Kottke and bassist Mike Gordon.

There’s no one quite like Leo. It’s been nearly 50 years since the improbable troubadour dropped the sound heard around the world via 1972’s 6- and 12-String Guitar on mentor John Fahey’s Takoma label.

Despite his gargantuan influence on countless would-be folk heroes, Kottke remains a singular figure on the acoustic guitar landscape. The bone-dry wit in his stage banter is arguably as instrumental to his act as his fingerpicking prowess.

I’ve been told that Neil Young is a fan of mono, and I am too. I think stereo remains an effect. We don’t really hear in stereo, we hear something more than that

He truly doesn’t need anything but his guitar and his creaky, bass-heavy voice to sing, play, and spin endlessly entertaining anecdotes that can quickly win over practically any audience.

Yet, the past two decades of the 75-year-old’s career have largely been defined by his duo with Gordon, who is most famous for frying oodles of Phish-head brains with his Phil Lesh–like sense of bass counterpoint and funky, George Porter Jr.–inspired grooves.

The Kottke & Gordon tandem has become like a bizarre musical version of The Odd Couple, with both men playing Oscar. Noon (ATO) is the duo’s third album, and comes a sloth-like 15 years on the heels of 2005’s Sixty Six Steps, which was preceded by 2003’s Clone.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Interestingly, Kottke hasn’t released any new solo albums in the meantime either, but he has toured steadily. Gordon’s Phish bandmate Jon Fishman brings drums to a handful of tracks on Noon, and guests include pedal-steel player Brett Lanier (the Barr Brothers) and cellist Zoë Keating (Imogen Heap, Tears for Fears).

Mike and I like to play in the same range. It can sound great, but it can be technically tricky to capture

On Noon, Kottke and Gordon sound as if they are sitting right in front of you. The songs are a balance of instrumentals – highlighted by the cheerful opener “Flat Top” and the dark and demanding “Ants” – and vocal tunes that include Kottke’s plaintive rendition of the Byrds’ harmonized classic “Eight Miles High,” as well as Gordon’s tongue-in-cheek take on Prince’s “Alphabet Street.”

What did you do instrumentally to create a cohesive sound on Noon?

There is no 12-string on the new album because we get in each other’s way. An electric bass with a guitar is a categorically difficult pairing, unless the guitar player is doing the responsible thing about playing with other instruments, which is to treat the guitar like a horn.

It’s considerate to be more left-hand oriented, and it’s a different kind of musicality. There’s much more about placement to consider when you’re playing in a band than there is for a solo guitar player. I’m a mess for bass players and piano players, because my style is crowded in the sense that it’s baroque.

There’s a lot of stuff happening inside. It doesn’t stand out on top like playing lines with a plectrum. When Mike and I play together sitting face to face, it locks well and we have room for each other. Recording is different.

How did you meet that challenge?

We recorded in several different settings using several different setups. Mike and I recorded together in New Orleans and Vermont. In Vermont, there was a room mic and a near mic on the guitar. In New Orleans, there was a near mic or two, and a couple of room mics. I recorded some tracks in Burbank with another setup.

I tracked a direct guitar signal in every place, just in case we needed it, and ultimately we did, because Mike and I like to play in the same range. It can sound great, but it can be technically tricky to capture. We were losing the air between us, which affects things like crosstalk, and you don’t want that.

We eventually got there. The simplest approach ended up opening it up the most. We found my sound by using a very crude, early form of occupying the stereo image with a guitar. You put the direct signal on one side and the mic on the other to varying degrees, and then the room mic, or mics, can be somewhere in the middle.

There’s one track where the guitar sounds different in a very good way. “Noon to Noon” was done in Burbank with Paul du Gre, who mastered this album and produced our first album. I have two B&K mics with very small capsules. Paul had them out in the room, in addition to the close mics.

I’m singing while playing that track as well, and the end result is essentially a multichannel evocation of mono. You can do that by paying close attention to the phase. Artists can also be our own worst enemies in the studio. I decided not to be and tried to stay out of it from a production standpoint.

The guitar on “Noon to Noon” sounds almost like a 12-string.

Yeah. And that sound is the extent to which the phase was not controlled. Just lately I’ve started going back to the old bluegrass approach, using a single mic. I haven’t done that live, and it’s very unnerving, because I’ve played otherwise for a long time. But you do away with all phase issues and a lot of latency disappears. It flummoxes digital recording the least.

Mike and I have recently made several videos independent of each other that are being synced together to promote the record. Using one mic has worked great in a lot of ways for me. It’s probably the way to go. I’ve been told that Neil Young is a fan of mono, and I am too.

I think stereo remains an effect. We don’t really hear in stereo, we hear something more than that. Don’t get me wrong: The sound Paul gets in Burbank is beautiful. But it’s a lot of work on that end, and it leaves room for error up and down the line, all the way through to mastering.

In the live video for “Flat Top,” there is a single mic in front of you and a direct line running from the guitar.

Paul asked me to plug in just in case we needed the direct signal for the transients, but we didn’t. I’ve had that guitar for over a year, but I only recently started liking it, and now I like it a lot. It was made by a guy named Kevin Muiderman.

The interesting thing to know is that he’s a plastic surgeon who lives up near the Canadian border. His main thing is rebuilding guys who’ve suffered farm accidents, such as falling under their threshers – really nasty shit. When he’s done doing that stuff, he builds guitars to unwind.

Can you detail the body style and what you appreciate about it?

It measures 14¾ inches at the lower bout, so it’s not big. The back and sides are made of Central American sinker mahogany with a Sitka spruce top, and I believe the fretboard is ebony. It’s got open-geared tuners because I don’t like the weight of sealed tuners.

When we began working together, I played a couple of Kevin’s guitars with Kevlar sandwiched in the middle of the top, so the top wood was actually just a veneer. I didn’t like that. For this guitar, we went back to the solid-wood top, but the braces are made out of wood with carbon-fiber composite in the center.

The braces don’t look that significant; they aren’t big, but the carbon fiber makes a big difference in terms of strength. Kevin is very into the science, which is to weigh everything. The braces are where they are because the weight distribution allows the top to be very thin.

Bach and a lot of baroque composers would leave long sections where they essentially tell you that you’re on your own for X amount of bars

Most of the new record sounds like you played in standard tuning, but it seems that “Flat Top” is in drop-D tuning and played in the key of D?

That’s right. So we’re in a real happy place on a guitar. It can get too happy if you do that too much.

“Flat Top” has a kind of magic that sounds complicated, even though it’s based on a simple progression. I would say “chord progression,” but I’m not sure you’ve ever actually strummed a chord! How did you work that composition into a seemingly endless cascade of fingerpicked arpeggios that flow like a musical snake?

That’s just how I wrote it. There is an improvisational section, and it’s kind of like a smell that you either like or you don’t. Mike and I have performed the song a couple times. We made a video of one that I believe is going to be an NPR Tiny Desk thing.

We also did one for Stephen Colbert’s show [The Late Show], and in the improvisational section we do strum. Actually, I strummed a chord and Mike played a double-stop.

Anyway, the idea is that I’ll get lost for a while and hope to find my way out. That’s part of the plan, and it’s an old deal. Bach and a lot of baroque composers would leave long sections where they essentially tell you that you’re on your own for X amount of bars, and then come back.

A lot of cadenzas were improvised. I came to improvisation very late, especially as a player. I’m not really an improviser, but I can make shit up for a while and hope not to ruin stuff.

Kottke plays “Gewerbegebiet” on a 12-string in a tuning analogous to open G, but with all the strings slacked down a whopping four and a half steps, until the lowest open string is Bb.

The composition is in the key of Bb minor, so the root is on the bottom string, but watch out for the major 3rd on the open second third string. He’ll often play “Vaseline Machine Gun” with the same tuning.

The composition is then in the key of Eb major with the root occurring on the fifth string and the major 3rd on the second string, as is natural in any tuning analogous to open G.

Is “Ants” a classically influenced composition?

It is, and “Ants” is in the same neighborhood as “Gewerbegebiet” [from 2004’s Try and Stop Me]. It’s rare to play against a tuning, and in both songs the key is different from the guitar tuning. It’s an open tuning, but it’s played closed, in effect.

I’m tuned to open G major for “Ants,” but I’m largely playing in D minor. That makes it very hard. The reason I got into that was because I frequently have to play the “hits,” like “Vaseline Machine Gun.” I needed something that wouldn’t require retuning the guitar but would take me out of that thing.

The real drawback of open tunings is that they sound like open tunings. You find one and it’s okay for a while, but then you’ve got to get away from that sound without boring the audience to death by tuning.

So I decided, “Why don’t I get out of it, but keep the tuning?” That’s how “Gewerbegebiet” and “Ants” happened, and I love doing it because it forces you to rely on your own invention. All your habits and hiccups just collapse.

- Leo Kottke & Mike Gordon's new album, Noon, is out now via ATO Records.

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com