"A Record Like This Was Destined to Be Made, and We Wanted to Be the Ones Making it”: Steve Howe on 50 Years of Yes's 'Close to the Edge'

"It was a really great time in our lives,” Steve Howe says, recalling the spring of 1972. His band, Yes, had hit the upper regions of the U.K. charts with their fourth album, Fragile, and much to their surprise, they did even better in the States. Tours were sold out, the venues were getting bigger, and FM stations were spinning the album tracks “Roundabout” and “Long Distance Runaround.”

As their unbroken, six-month string of concert dates began to wind down and they considered their next recording, the group felt as if they had the wind at their backs.

“Our spirits were very high,” Howe says. “We were young, enthusiastic, and adventurous, and we had this incredible breakthrough success with Fragile. We saw our next album as a real opportunity to prove our worth as a band. The door had been opened and we weren’t going to go backward. We wanted to sharpen our skills as far as writing and arranging.

"Concerts come and go, but a record is forever. I think we all had a sense that whatever we did next, it had to feel like some sort of definitive statement. A record like this was destined to be made, and we wanted to be the ones making it.”

Vast, enigmatic, full of moments of spectacular grandeur and ever-changing hues, Close to the Edge is the Lawrence of Arabia of progressive-rock albums. Comprised of just three tracks – the dizzying side-long, 18-minute title track, the equally sprawling mini epic “And You and I,” and the whacked-out, hyperactive jazz-funk album closer “Siberian Khatru” – Close to the Edge documented Yes operating at the peak of their musical powers.

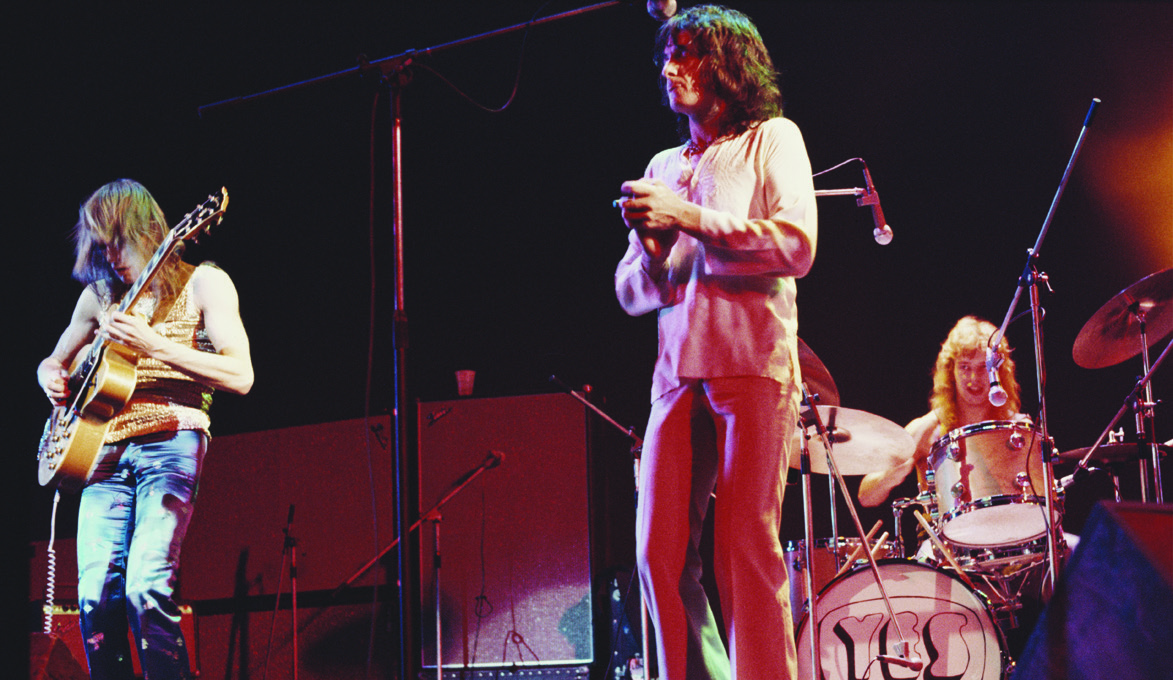

At that point, the group consisted of Howe, singer Jon Anderson, bassist Chris Squire, keyboardist Rick Wakeman, and drummer Bill Bruford. Anderson was deep in thrall to Hermann Hesse’s spiritual self-help novel Siddhartha, as reflected in his cosmic lyricism. The band responded by pulling out all the stops, surging through each passage with unbridled zeal and relentless creativity.

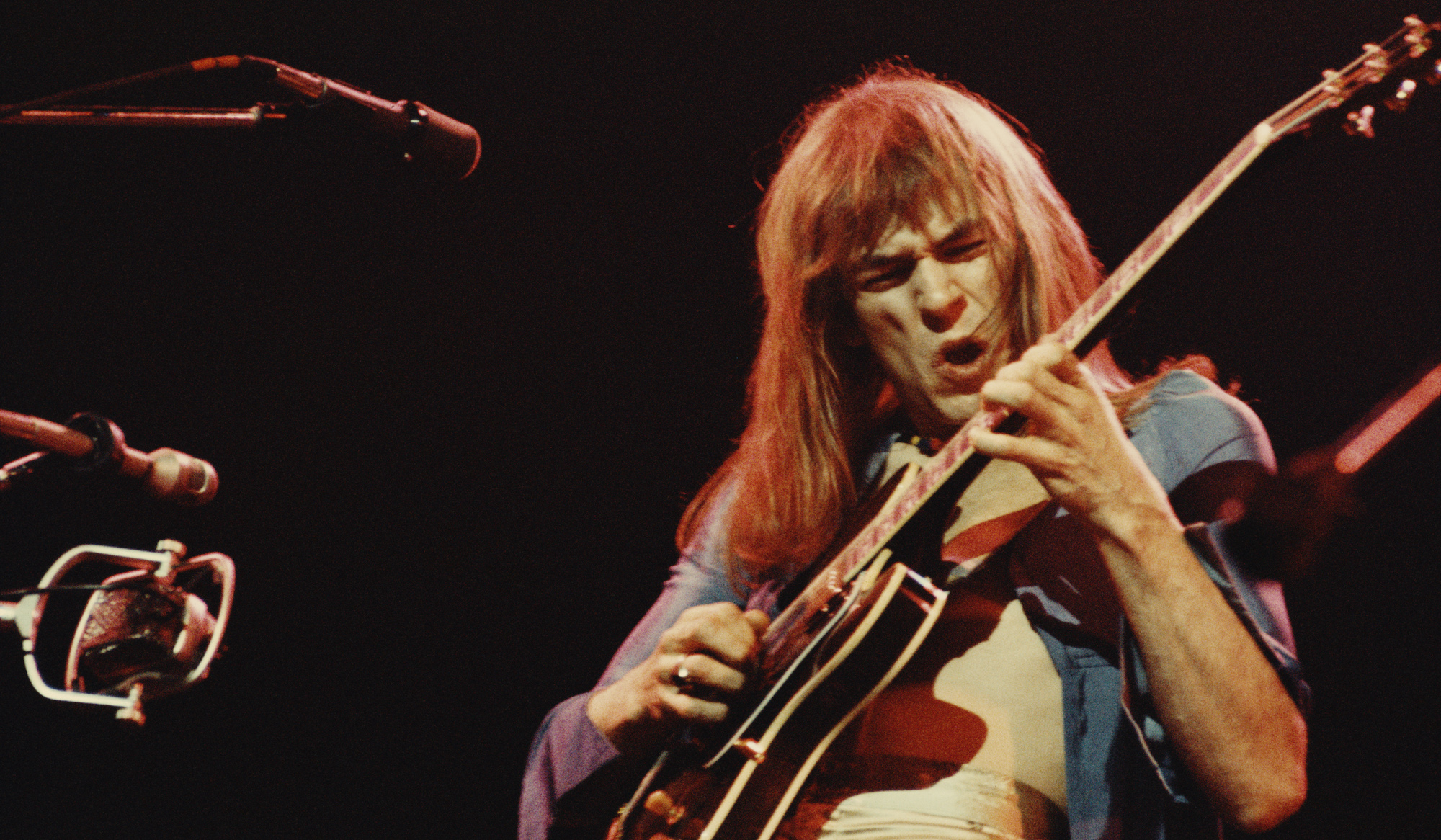

For Howe, the widescreen canvas afforded him the opportunity to exhaust his wily eclecticism. One minute he’s unfurling gnashing, Hendrix-like riffs, the next he’s basking in elegant acoustic serenity. Each track yielded moments of meticulous plotting or go-for-broke improvisation. For a divine example of the latter, his nearly three-minute album-opening blitz is an epochal art-rock masterstroke. As definitive statements go, his playing on Close to the Edge checks all the boxes.

“We were quite fortunate in that we could do whatever we wanted,” Howe recalls. “We didn’t really have any kind of outside pressure to follow up a hit. I think, fundamentally, we were helped by the fact that Yes wasn’t a singles band.

"Obviously, ‘Roundabout’ launched our previous album, and that was all well and good, but we seemed to disregard that fact. Yes were now established, and we felt like Close to the Edge didn’t need a single. If we wanted to do a 10-minute song or even something that was longer, we could do it. And as it turned out, there were stations, particularly in America, that would play the longer songs. We lucked out.”

Close to the Edge marked the second consecutive album on which the band lineup remained unchanged, but shortly after the recording sessions finished, Bruford announced that he was leaving to join King Crimson.

“We were all taken aback, obviously,” Howe says. “Up until it happened, we felt as if things were pretty solid among all of us. Bill left mainly because of his conflicts – or should I say challenging times – with Chris wanting him to dot every bass beat with the bass drum or something. Bill had his principles and his musical taste that he wouldn’t revert from, so he left.”

Bruford, for his part, compared the jigsaw-like process of making Close to the Edge to “climbing Mount Everest.” His replacement, Alan White, stepped in with little time to prepare. [Sadly, White died on May 26, 2022, shortly after our interview with Howe.] “Fortunately for us, Alan White was on the scene and was already hanging around,” Howe explains. “He joined us in the nick of time, as we had a tour to start.”

That trek, a mammoth nine-month stint across North America, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Australasia, would be documented in the triple-LP Yessongs, released in May 1973. “All in all,” Howe declares, “we were quite lucky.”

Despite its lack of an obvious single, Close to the Edge bested its predecessor on the charts and received almost unanimous raves from critics (even the NME, issuing a somewhat mixed assessment, concluded that “on every level but the ordinary aesthetic one, it’s one of the most remarkable records pop has yet produced”). Over the decades, the album has grown in stature among critics and musicians alike, and it’s now generally regarded as a classic.

It routinely tops progressive-rock polls and has been cited by guitarists like John Petrucci, Steve Stevens, and John Frusciante as a major influence. In a recent interview, Wakeman called it the band’s finest album, and Howe agrees. “It’s got all the attributes a timeless record should have,” he notes. “It’s interesting, challenging, and exciting. It was certainly interesting and challenging to make, and dare I say, I think we broke new ground.

"You never know how something is going to be perceived as you’re recording an album. You might think that it’s going to be a landmark, but there’s just no way to judge that in the moment. You just do your best and hope for the best. So 50 years on, it’s incredible to see the long life it’s had. I hear other musicians say nice things about it, and to see it being voted best prog album of all time, it’s all very delightful.”

Before recording Close to the Edge, Yes had toured with the Mahavishnu Orchestra. I understand seeing them had a big impact on you and Jon Anderson.

"Oh, yes, but for me it started in the early ’60s. John McLaughlin was playing beautifully with Herbie Goins and the Night Timers. He had his amp on a stool, which I then started doing – I wanted it at ear level. With Herbie Goins, John was having fun being a really creative guitarist, but he hadn’t yet found his style. He found that with Mahavishnu and went on to greater things.

"Anyway, Yes had done some shows with the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Jon and I were knocked away; we felt they were the most remarkable band since the Beatles. They were totally different, and nobody can really top the Beatles, but as far as pure musicality goes, Mahavishnu was just so impressive. That’s why Close to the Edge starts with a kind of manic presentation. You wouldn’t expect a song or album ranting and blaring away for three or four minutes."

The Fragile tour was quite extensive and continued for the first month or two that you were recording Close to the Edge. How much actual writing time did you have before going into the studio?

"There was a bit. Jon and I established a pattern for writing and arranging together. It started with The Yes Album and into Fragile, where we discovered that one guy presenting a song could get knocked down very easily. But two guys? Much harder.

"We did have an awful lot of Close to the Edge arranged – parts of 'Siberian Khatru' and then 'And You and I.' Of course, a lot of credit goes to the general collective of the arranging style of the members of Yes when we were together. Jon and I had the imagination that things would project further than our little cassette once we got in the studio with everybody."

You did a bit of preproduction. Were the tunes fully fleshed out before going into Advision Studios?

"Not fully. We had our crude cassettes of ideas. I remember we went to rehearse in this dance ballroom – the Una Billings School of Dance in Shepherd’s Bush. We’d go in for afternoons. Bill wasn’t involved in arranging as much as Chris, Rick, and me, and Jon, of course.

"We were trying to find how to play these tunes and how we go from one to another. We were developing them together. The rehearsal period was fairly intense. We came out of it with mockups of sections of the music, if not parts of all of it. Some of the inventive arrangements came about in the studio. What I mean is, they became clearer to us in the studio. We’d figure out how to improve them.

"It would have been a waste of time and money to go into the studio saying, 'Okay, we’re going to start Jon and Steve’s song ‘Close to the Edge.’ We would have been there forever. We only had blocks of days, not weeks or months. We would do shows and go back into the studio. I suppose our manager was trying to get his commission, so we kept getting put back out on the road. It didn’t leave a lot of time for the studio."

Obviously, the band did a lot of overdubbing.

"Of course. We did an awful lot of overdubbing when we cut tracks. There was a lot of creativity on the part of Chris. He always liked to improvise, as did Rick, but he wanted structure around those improvisations. And he was right – there is a structure that you need so that somebody can then improvise.

"That was the key to a lot of Chris’s rather ponderous and slow approach to coming up with his final bass parts, because he was always thinking, Well, I’ve got to commit to this. And Bill was like, I’ve got to commit, too, so let’s get on with it!"

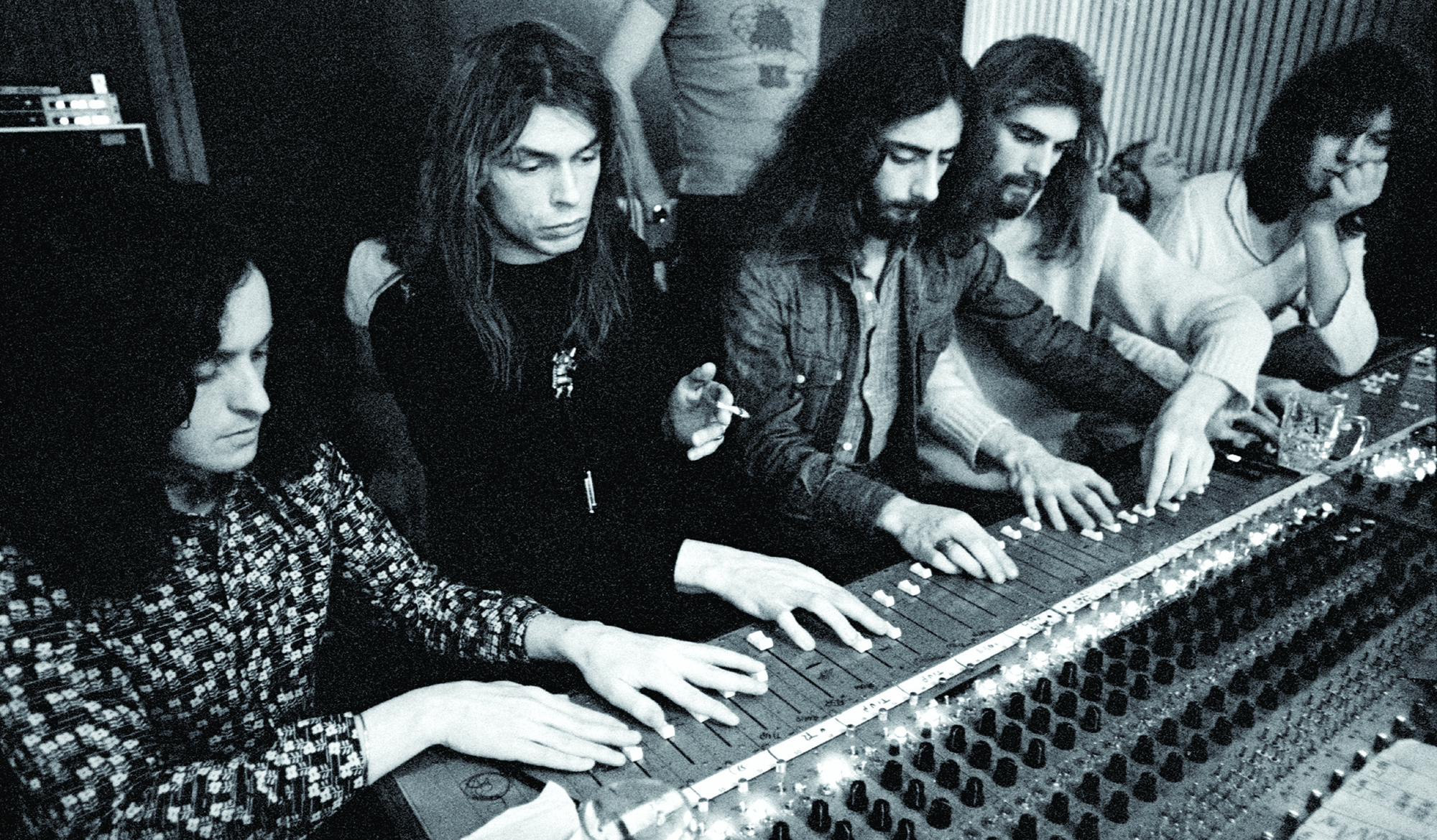

Yes had been working with Eddy Offord as engineer and co-producer for a number of years. He seemed to juggle his time between your band and Emerson, Lake & Palmer. What made him the go-to guy?

"He had been engineering the band before I arrived. On The Yes Album, we chose him to co-produce because we felt confident and comfortable with him. He had a strong personality, but he could be fun. Actually, you mention ELP – they might say that we stole him from them. [laughs]

"When it came down to the actual hard work, he was very good. If Jon was doing guide vocals in a booth, Eddy would say, 'That was a good take, but you went wrong here,' or 'I think you could do it better there.' He was our go-to opinion. He held that gauntlet in his hand, but he never abused it. He always got the best of us.

"Eddy was also very good with his editing. We would have different takes, and choosing which one worked best took skill and the right set of ears. Also remember, he was editing on tape – you literally had to cut them and splice them together. That’s a skill, and Eddy was great at it. If he had been a rubbish editor, he probably wouldn’t have lasted with us."

Your opening guitar solo on the album’s title track is quite remarkable. Was it an improvised, one-take deal or planned out?

"What I opened with [he sings the part], that was a structure that I used another guitar to harmonize with, but once it goes to the next part [he sings again], that’s an improvised take. There are so many meters, either 16 or 32 bars, and we knew we were going to do them. Those breaks had to be strategically placed in our minds. I think of myself as a composer in a way, but a lot of my music is improvised."

Which guitar did you use on that opening solo?

"Around that time, I did a strings advert for Gibson guitars, and they said, 'We’ll give you a guitar.' And I said, 'Well, I’ve always wanted an ES-345, with stereo wiring,' so they gave me one, and I plugged into two Fender Dual Showmans – or it might have been one Dual Showman and another Fender amp.

"That guitar became the Close to the Edge model, really. I liked to feature a new guitar on an album. On The Yes Album, it was the Gibson ES-175, and on Fragile I played the ES-5 Switchmaster. Playing a new guitar on an album was exciting. The guitar would feel fresh in my hands, and it made me excel in a new way."

You used a descending guitar line from one of your old songs called “Black Leather Gloves” for the “Total Mass Retain” section.

"Well, yes. That’s a reference to my old band, Bodast. We had recorded an album, but it went down the tubes and disappeared completely. The label folded and didn’t put the record out. So I said, 'Well, some of these riffs are quite good. I’ll throw them at Yes and see if they like them.' Some of my riffing came from that album, as it did with the 'Würm' part of 'Starship Trooper.' It was like a tribute to that band. The music came back, and I was proud to re-use it."

Your singing on the album is extraordinary. The way you harmonize with Jon, particularly on the “I Get Up, I Get Down” section – he’s talked about how influenced he was by the Beach Boys and the Association. Did those bands impact you, as well?

"I didn’t quite know the Association myself, but I certainly knew and loved the Beach Boys – not that I thought for a minute that Yes sounded anything like them. Actually, I hadn’t sung in public or on records until I joined Yes, but on The Yes Album there were harmonies that I could perform in my sort of naïve, untrained way. I could sing low stuff quite easily. I was a bit nervous and was sort of bluffing a bit, but in a strange way, once I started, it all happened quite fast.

"I think I benefitted from my not knowing the rules. So it’s been nice: Over the years, I’ve had more and more comments from people who like the sound of my voice."

What kind of acoustic guitar did you use on the “Cord of Life” section of “And You and I”?

"The main guitar I used was a Martin 00-18 that I bought in 1968, which is the best flattop acoustic I’ve ever had, even though I now use a Martin MC-38 Steve Howe model. Because of the cutaway, I’m much happier on that guitar. I had the 00-18, but I also used a beautiful Guild 12-string that Chris Squire had owned. I was very tempted to buy it. I think I did buy one in the end.

"There were those ones, and actually, now that I think of it, here and there I did some overdubbing with a Gibson called an FDH. It’s a very rare guitar that came to England under the Francis, Day, and Hunter [FDH] emblem. It’s a guitar I still love. It’s the second Gibson I ever bought – it cost me 50 quid.

"It’s basically a big archtop guitar, a little bigger than a 175. I still love that guitar. I’ll give you a scoop, in fact: Chris actually tracked with that guitar. His bass on 'Roundabout' was actually tracked with the FDH with a pickup on it."

How did you come up with that pedal-steel part in the “Eclipse” section? Are you using distortion and delay on it?

"Probably. But it wasn’t a pedal steel; it was a lap steel, or a Hawaiian steel – call it what you like. Nowadays I only play steels with legs because I like the guitar to be rigid, and then I can play well. If it’s on my lap, it’s hopeless, because I’m working a volume pedal as well.

"At the time, I was just sort of learning about the lap steel and its possibilities. By the time of 'Going for the One' [1977], I played that whole song on a steel. I’d really worked on my steel playing after Close to the Edge."

“Siberian Khatru” features a riff that’s pretty much the basis for the song. How did that come about?

"Well, there’s two riffs, really. There’s the part [he sings] that I play for probably half of the song. I’m playing that with some different approaches, sometimes with a Leslie guitar, sometimes moving octaves around. Basically, that was one of Bill’s gems. He brought that in.

"It was a knockout to have that riff. I adopted it, I loved it, I played it. It’s a fundamental part of the song. But the other riff – sometimes Bill would do this if he wasn’t sure how to finish a line: He’d just mouth something, like a scat singer. That happened on several occasions on those first three albums. Bill was remarkable like that. I don’t think he realizes how much he contributed. But in the spirit of the arranging of Yes, it was the giving and taking of ideas, and we were really fluid with that."

You played two solos in the song, the second of which, the clean solo, you recorded without hearing what you were doing, as I understand.

"That’s right, yeah. We didn’t often record guitars with me standing in the big studio. I liked being in the control room, where I could really hear the music. I’d done some solos, but I didn’t like them. They just weren’t doing much for me. I had the 345 all set up and I was going to tape, and I said, 'Let’s try one without listening.' Everybody thought, He’s gone mad. But okay, do that. I played, and I didn’t even realize what I’d done, but I could see it in my mind.

"It was a different way of playing. When we listened back, I went, 'Okay, I like that.' Everybody else liked it, too. It was an eye-opener for me, because I don’t know that I would have ever played like that if I’d heard what I was doing. I truly didn’t know where I was going at the time. By not hearing it and just thinking about my fingerboard and my positionings, it came out quite good. I was delighted."

Alan White joined the band three days before the tour to support the album began. What happened there?

"It happened quickly. I mean, Aynsley Dunbar was pretty unhappy that I didn’t invite him. We were pally and we’d played together on a few recordings in the studio. I loved his drumming. When it was announced that Alan got the job, Ansley said, 'Why didn’t you give me a call? I would have come down.' But that wouldn’t have made any difference, because Alan was in the circle of people that we knew.

"He was friendly with Eddy Offord, and he was hanging out in the studio. He may have even jammed on Bill’s drums for a laugh here and there. Basically, we looked around and thought, Oh, Bill wants to leave – Alan’s already here; why not ask him? His reputation was such that we could ask him, and he said yeah."

How many rehearsals did you have with Alan before the tour? I’m guessing not many.

[laughs] "Well, I wouldn’t think no more than a couple. I don’t know how it’s possible that he got onstage after having two or three days to learn the album. We did put him through it, you know what I mean? I mean, even though we knew the songs, we hadn’t actually played them live ourselves.

"It was a remarkable learning curve. How anybody could come in and play Close to the Edge, let alone anything else that takes the highest level of technical and musical skill – it wasn’t an easy gig to step into, but Alan did his best to listen and practice. He tried a bit of this and a bit of that. We asked him to get it right as much as he could. And he did."

Previously, Yes played theaters and big clubs; even on the Fragile tour you played the Whisky in L.A. But you moved to arenas on the Close to the Edge tour.

"There had been a bit of time when we could tolerate those places – it felt like when I was playing gigs in England in the ’60s. But the Whisky… I’m cautious to say it was an awful place, but in a way it wasn’t really suitable for a band like ours. However, everybody played there, and I think its reputation preceded its reality.

"It was a place to be seen at – a place to add to the list of venues you’ve played. From the Whisky we made the jump to the Hollywood Bowl. We had played as a support band for several years in America. One night we played with Jethro Tull, the next night it was Grand Funk Railroad, and the night after that it was Mountain. We opened for acts that were on the Premier Talent roster.

"Actually, the very first gig we did in [North] America was in northern Canada. We had gone to New York and we got scared in our hotel; it was next to a fire station and all hell was breaking out from the noise. Then we went to Edmonton, Canada, for our first show with Jethro Tull.

"We went onstage and we were like, Oh, yeah, this is what we came for, because there was a captive audience of Jethro Tull fans. Nobody knew us hardly, but we went down really well. They liked us instantly. After that, we were unstoppable."

When you finally hit arenas, did you feel as though you were in your natural element?

"Yeah, we were ready. By the time Close to the Edge came, we were out there on our own. I think we might have invented 'the evening with' lineup, where we didn’t have an opening act. We were geared up to do a whole show of our own music. We knew our time had come, and it happened, quite remarkably."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song

"When they left town, I went to the airport and got to meet Ritchie, and he thanked me for covering for him." Christopher Cross recalls filling in for a sick Ritchie Blackmore on Deep Purple's first-ever show in the U.S.