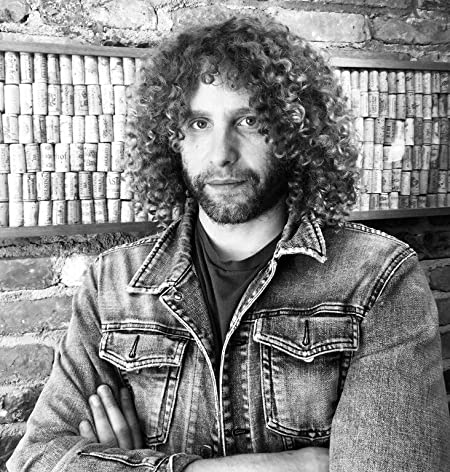

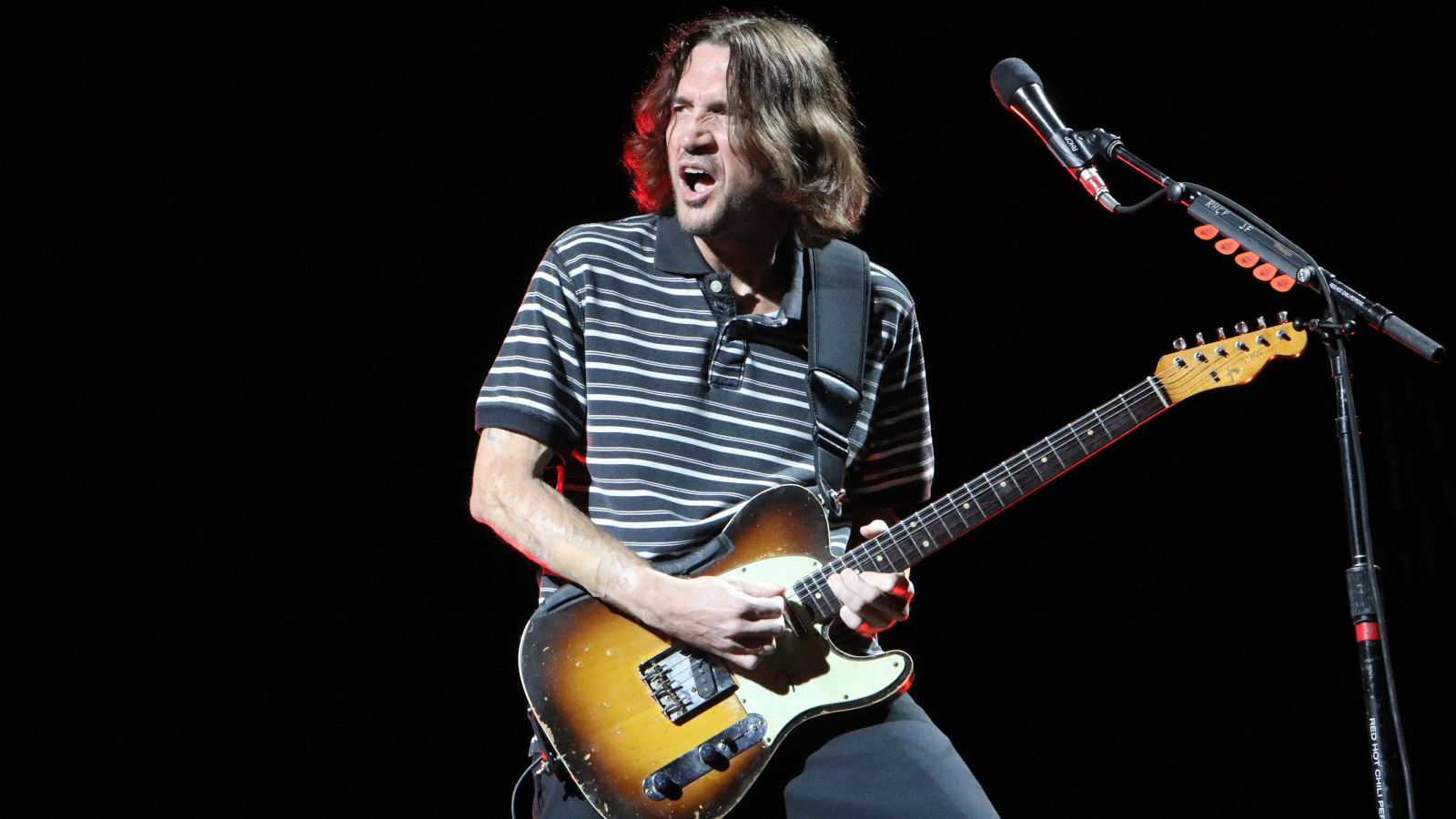

“A Lot of What I’ve Wound up Having to Say Has to Do With Vulnerability”: John Frusciante Gives His Most Revealing Interview Yet

The Red Hot Chili Peppers guitarist comes clean about his love of Eddie Van Halen, his attraction to clean tones and the importance of staying vulnerable

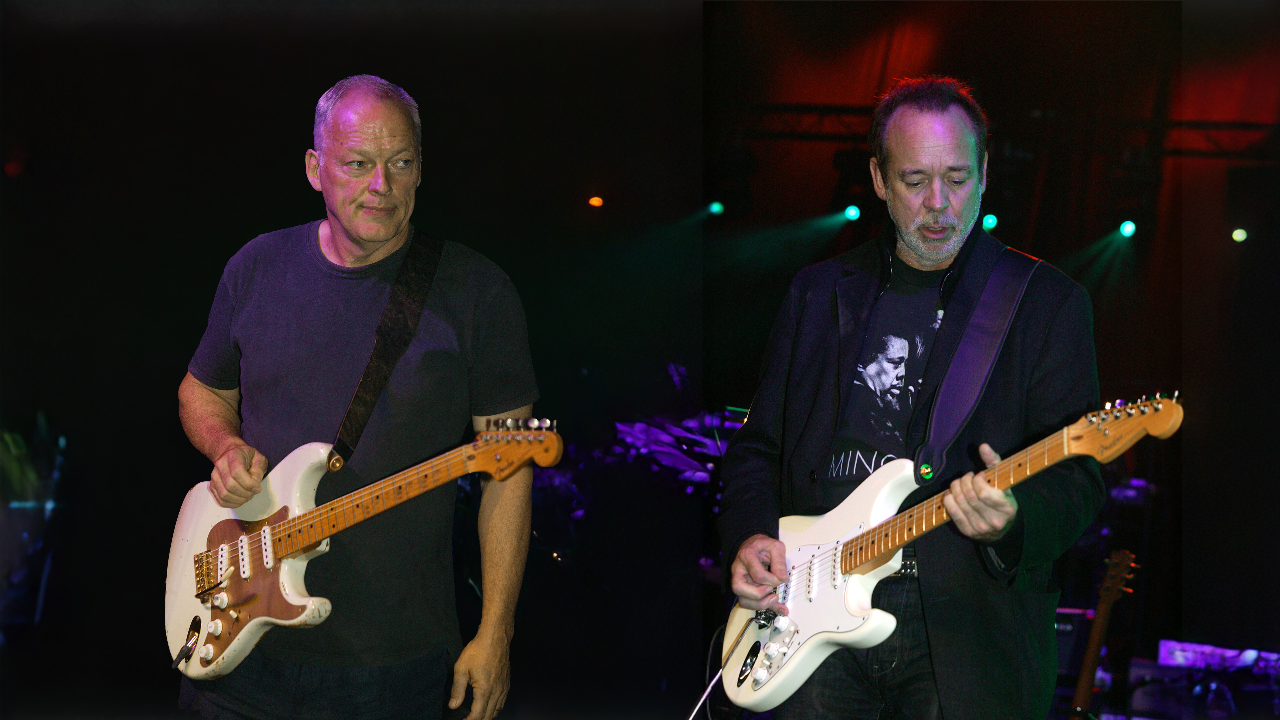

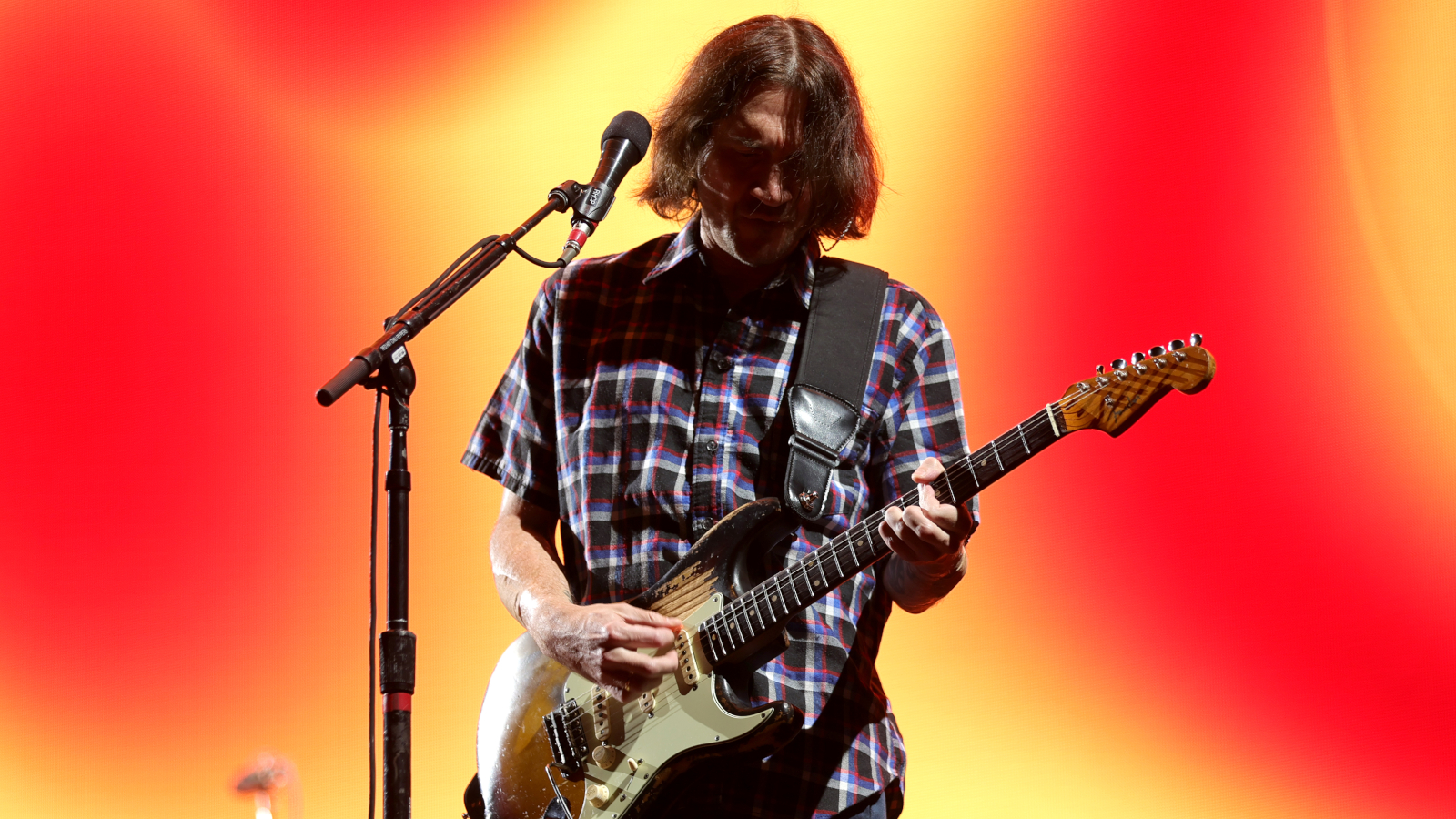

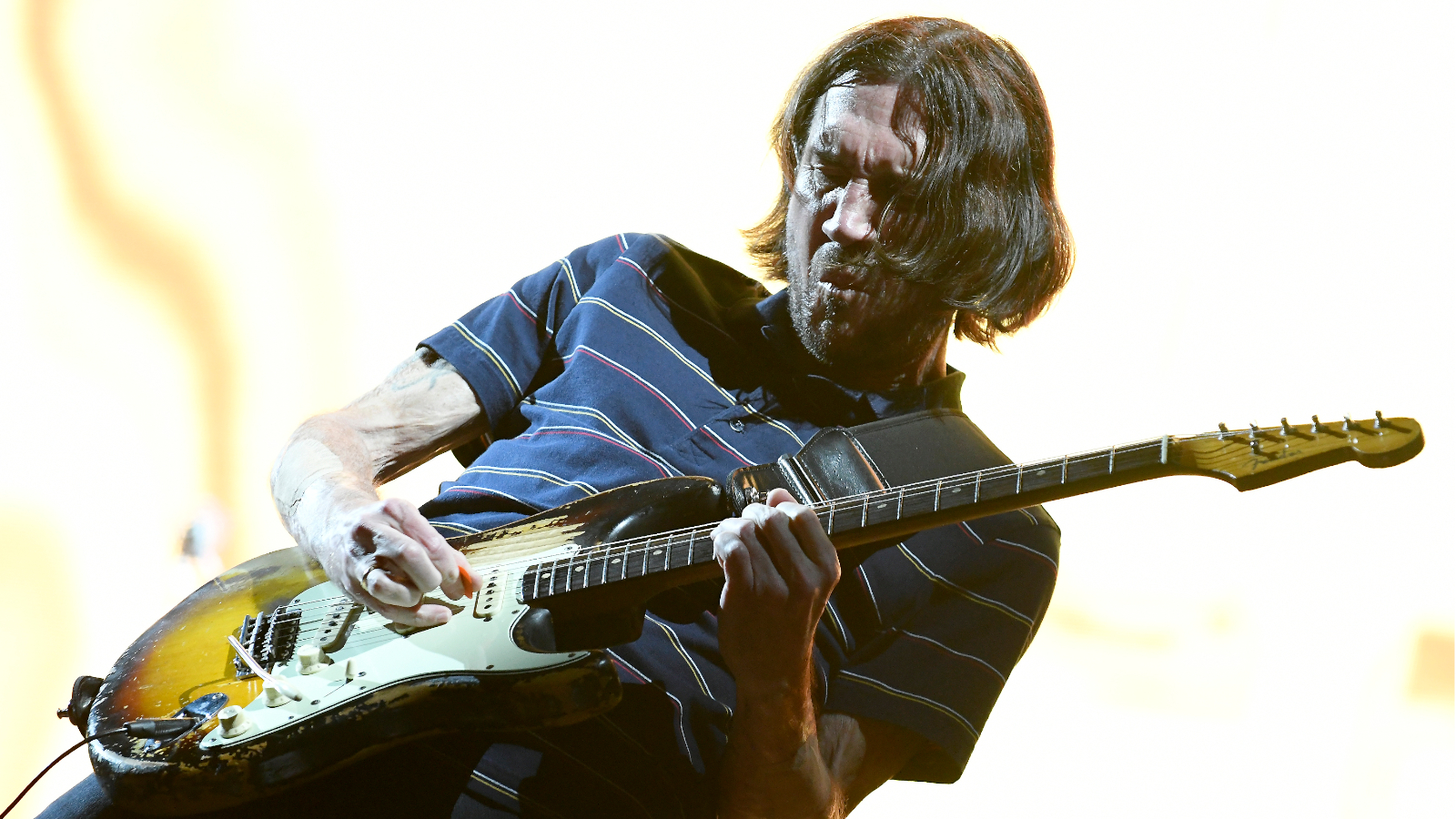

Back in April 2022, the Red Hot Chili Peppers released Unlimited Love, their 12th studio effort and, more significantly, their first with John Frusciante, arguably their most fan-beloved guitarist, in more than 15 years.

If some listeners felt like they had waited a lifetime for this reunion album – and it’s quite possible that a few younger ones actually had – they didn’t have to hang on too much longer for the next one.

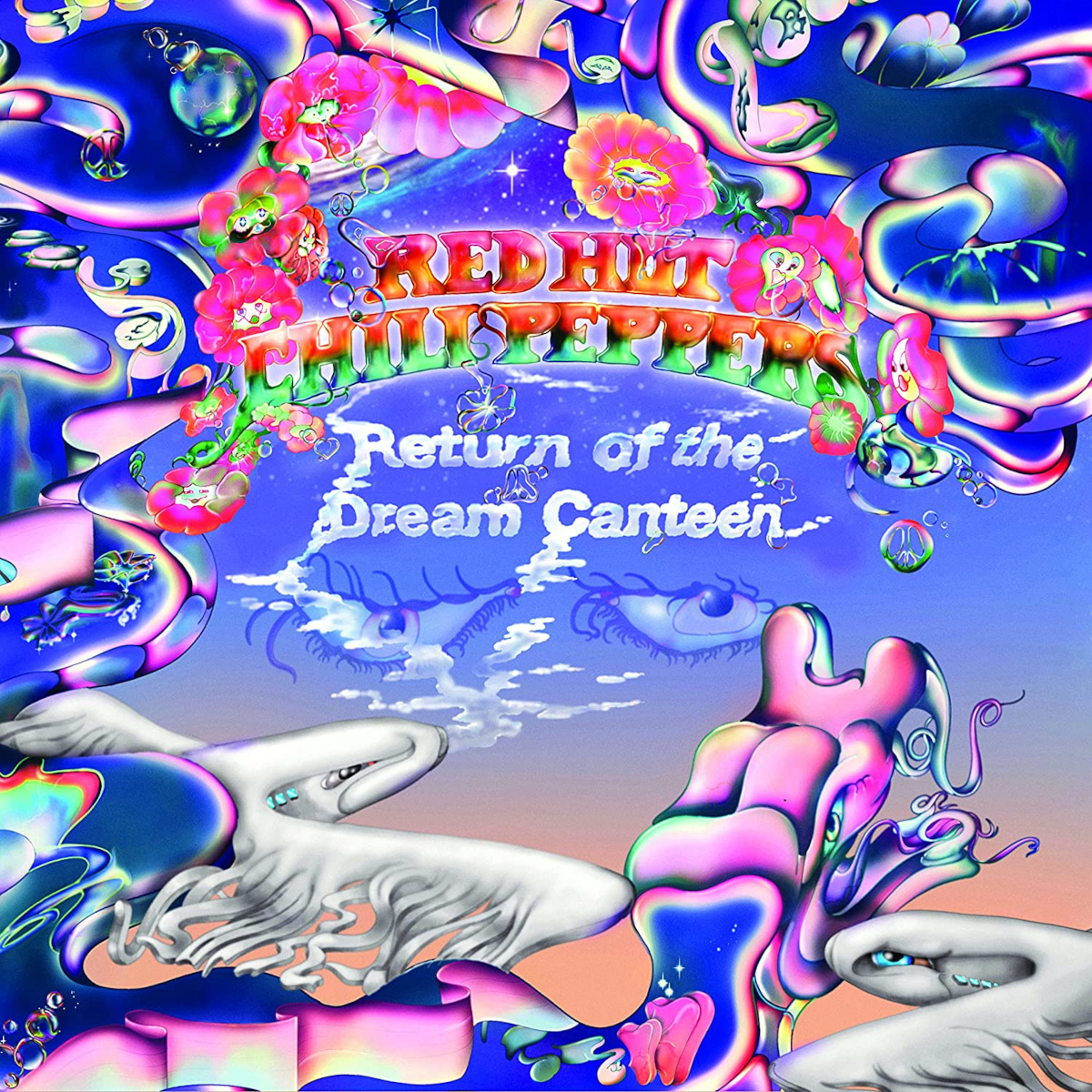

Rather, here we are just a handful of months later, and the Chilis – which also include singer Anthony Kiedis, bassist Flea and drummer Chad Smith – have now followed up the 17-track, hour-plus Unlimited Love with the similarly 17-track, hour-plus Return of the Dream Canteen (Warner Records).

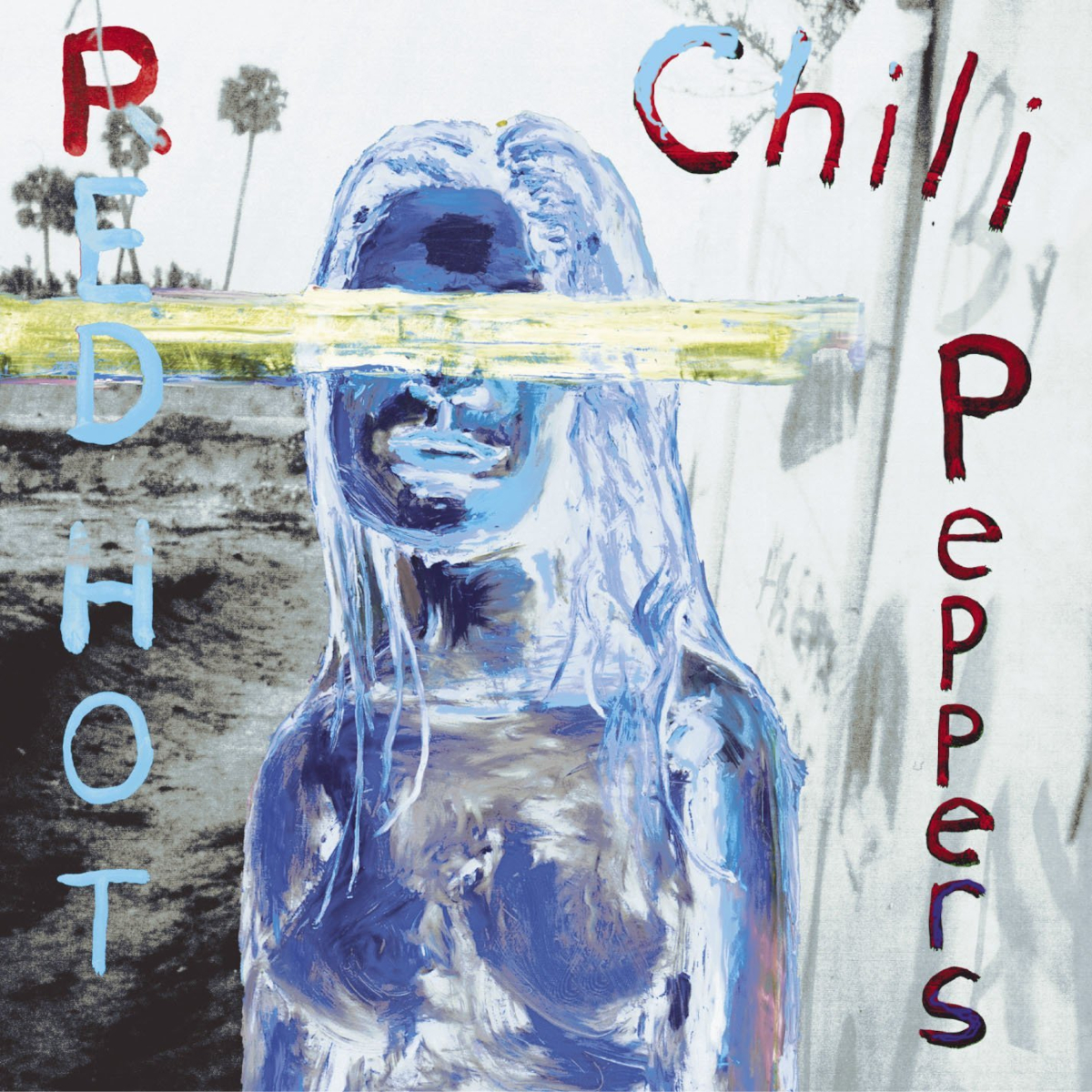

Released in October 2022, Return of the Dream Canteen is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 13th studio album and the 7th featuring Frusciante.

Released in April 2022, Unlimited Love is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 12th studio album and the 6th featuring Frusciante. It follows the 2019 announcement of his re-return.

Released in 2006, Stadium Arcadium is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 9th studio album and the 5th featuring Frusciante. The guitarist quit the band for a second time in 2009.

Released in 2002, By the Way is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 8th studio album and the 4th featuring Frusciante.

Released in 1999, Californication is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 7th studio album and the 3rd featuring Frusciante who made his miraculous return the previous year.

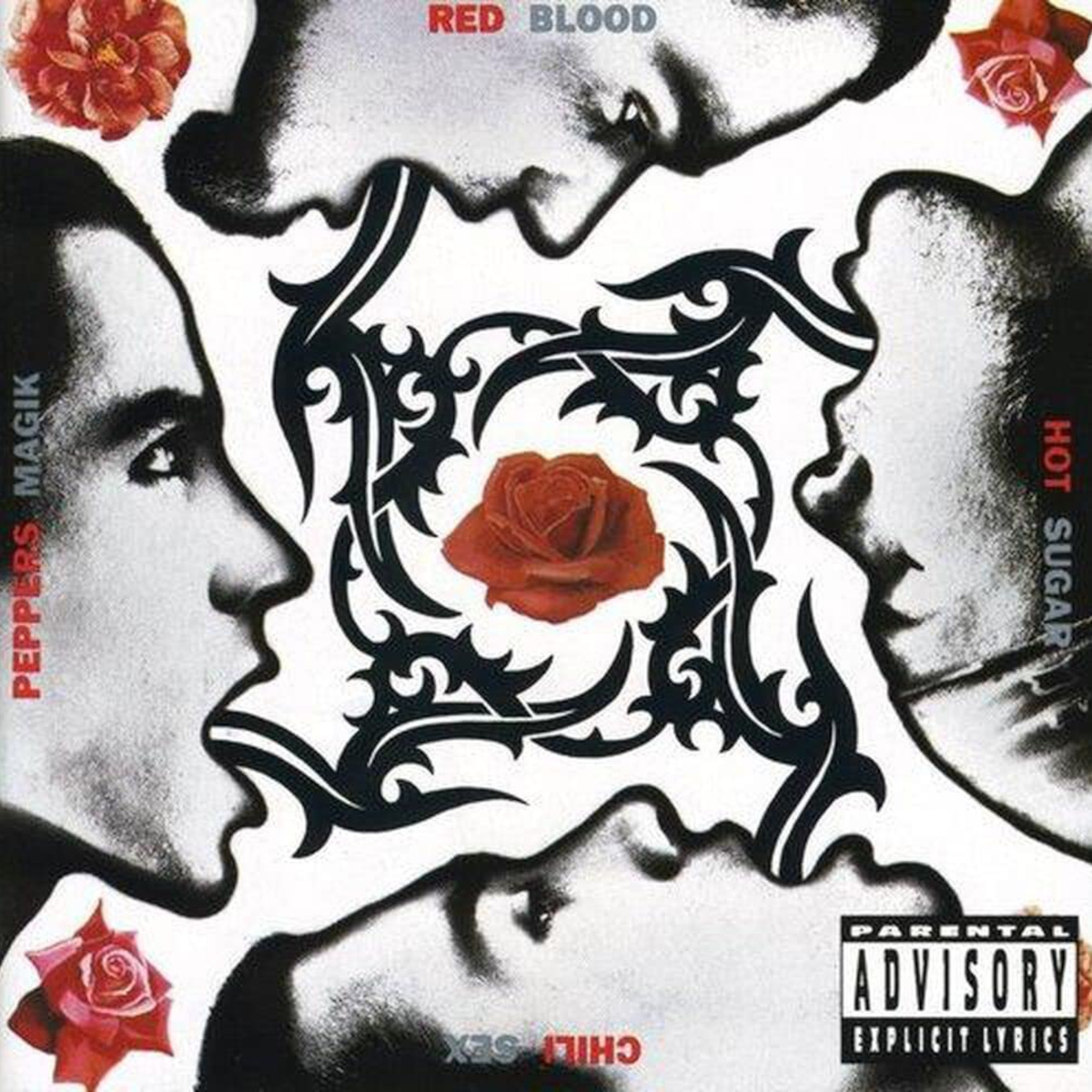

Released in 1991, Blood Sugar Sex Magik is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 5th studio album and the 2nd featuring Frusciante. The guitarist quit the band the following year while touring this breakthrough LP.

Released in 1989, Mother's Milk is the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 4th studio album and the first to feature Frusciante. The teenage guitarist was recruited following the death of founding member Hillel Slovak the previous year.

Given that, this time, the Chili Peppers entered the studio with a clutch of ideas and came out with not one but two new albums – and double albums at that – it can be surmised that Frusciante’s return has borne plenty of fresh creative fruit.

As the band has headed out on the road to play the new music and the classics onstage, that renewal has only continued.

“Aside from one or two shows in smaller places, all these shows have been a size that we’ve never done before,” Frusciante says. “We’ve been playing stadiums that are generally between, like, 40 and 60 thousand people a night.

There’s so much happiness being generated from the audience that sometimes it’s overwhelming

John Frusciante

“It’s a lot of people, and the energy’s very intense. There’s so much happiness being generated from the audience that sometimes it’s overwhelming.”

Nevertheless, Frusciante’s guitar playing has remained rock solid and unshakeable, not to mention mind-bendingly awesome.

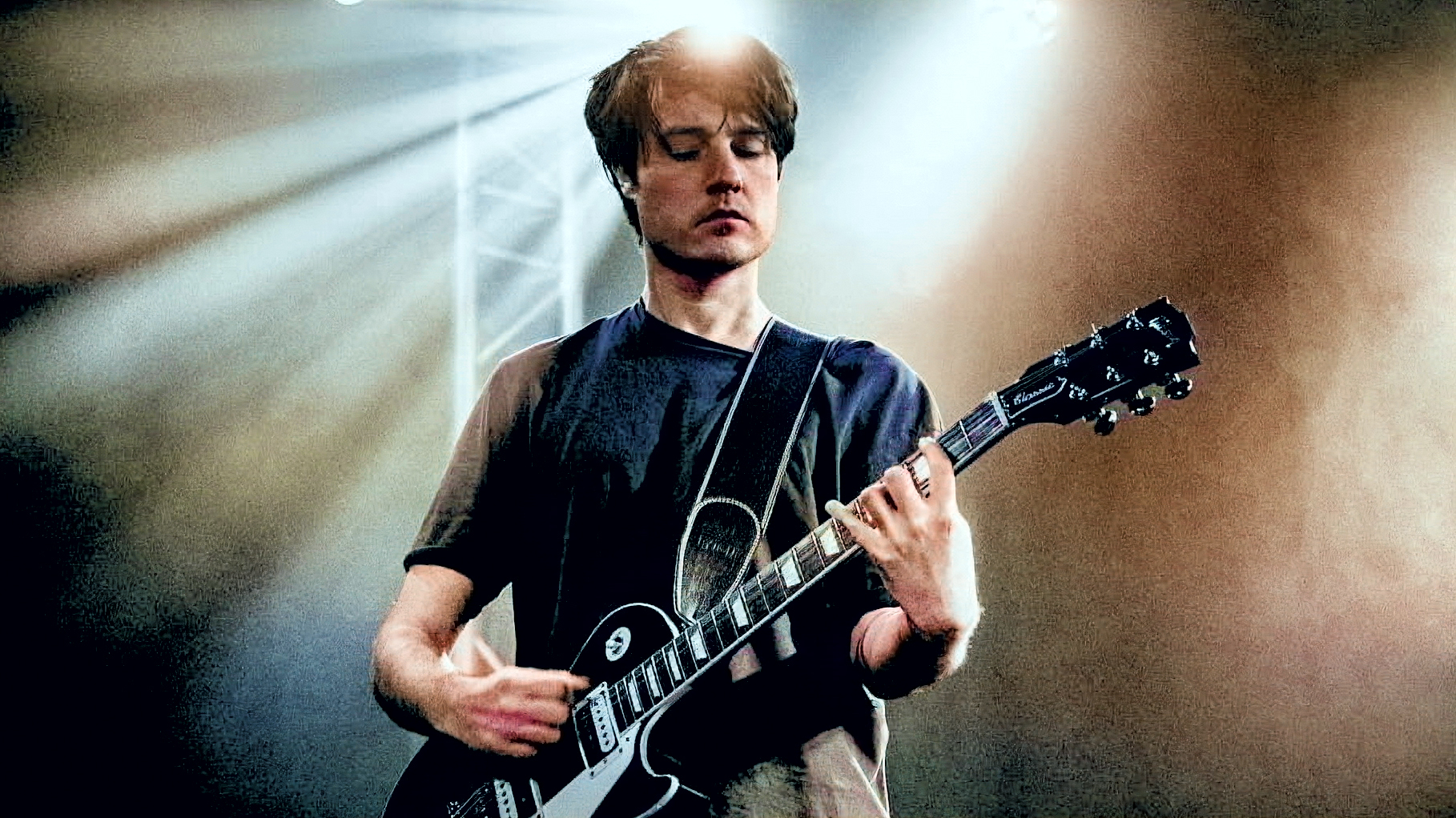

Now 52 years old, he evidences the same beautifully idiosyncratic playing style – the elastic, slinky rhythm work; the alternately fluid and furious chording; the feedback-drenched, acid-fuzz solo freak-outs; the inspired improvisations; and the almost telepathic instrumental interactions with Flea and Smith – that made him an alt-rock guitar hero at the tender age of 21.

But everything feels both heightened and boundless. There’s an increased focus and intensity, and also what appears to be a greater willingness to let loose and take his playing right to the edge.

It’s beautiful when you feel like somebody’s putting themselves out there and taking a risk

John Frusciante

“It’s beautiful when you feel like somebody’s putting themselves out there and taking a risk and just barely holding on, and it could become terrible at any moment if they lose it,” Frusciante says. “I love the openness of that.”

In a wide-ranging interview with Guitar Player, Frusciante spoke about that openness, as well as the many aspects of his playing style and practice regimen that have helped make him the player he is today.

He also took us inside Return of the Dream Canteen and the creation of some of its standout tracks, and discussed how he employs technical facility and knowledge of theory in the service of making an emotional connection on his instrument.

“It’s the vulnerability that I think is most appealing,” he says.

Since your return to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, the band has written and recorded close to 50 songs and released two albums. That’s a significant amount of studio work. But you also returned to the stage with the band. How has it been to perform with Anthony, Flea and Chad again?

I came back into the band in a spirit of giving

John Frusciante

It’s a real different experience, just because of the size of the stadiums. It pulls a lot out of you, especially because I came back into the band in a spirit of giving. I really wanted to play for people, you know? But when we made the records, it was more about playing for the other guys in the band, or playing something that I’d want to play for my friends.

But going out onstage, there’s times where I go up to the mic to sing and I make eye contact with people, and I see two people that are clearly in love and really happy to be there, or a little kid who’s really happy, or a young girl who’s jumping up and down, or a group of guys that are jumping around in a circle because they’re so happy that we played the particular song that they really like.

Sometimes those moments, I start crying. Or I get choked up and I can’t sing and I have to shut my eyes and stare down at the ground and collect myself.

That’s intense.

There’s a lot of emotional moments like that. And I don’t know that in the band we’ve ever been so appreciative of being there with each other before. Because we have this lifetime behind us of these meaningful moments playing together. It’s very important to us. We all feel very supported by each other.

Every second on the stage feels worthwhile

John Frusciante

One very cool aspect of these shows it that you, Flea and Chad begin the set with an instrumental improvisation. When you’re dealing with audiences in venues of this size, the goal of a rock band is usually to hit the stage and blow the fans’ hair back. But you guys approach the music in a more open and creative way.

Yeah. It’s a good way to really get in touch with the particular energy that’s there that night. Because every crowd is different and every venue feels different, and we’re also in a different mood every night.

So by improvising right at the beginning, we get in touch with what the spirit of the moment is, and oftentimes that sets the tone for the rest of the show. And you know, throughout the show there’s lots of spontaneity.

Every time there’s a solo, whether it’s a song that we don’t play often or a song that we play every night, I feel really creative in those moments. Every second on the stage feels worthwhile.

Return of the Dream Canteen is culled from songs recorded during the same sessions as Unlimited Love. When you were in the studio, did you have an idea of which songs would ultimately wind up on which record?

I definitely gave it a lot of thought, but it really came down to what order we decided to mix the songs in.

I had my own personal idea of what would make a good second album and what would make a good first one, but I didn’t feel so strongly about it

John Frusciante

I had my own personal idea of what would make a good second album and what would make a good first one, but I didn’t feel so strongly about it that I took the trouble to go to the band and say, “Look, guys, before we mix anything, let’s make this decision right here and now.” I planned on doing that, but I just never did.

It seemed like the way it went was sometimes Anthony would suggest mixing a particular song, sometimes I would, sometimes maybe Flea would. And we just kind of trusted that whatever was going to be was going to be. There really was no conscious idea about what the difference between the two albums should be.

That said, there were certain songs that I felt should wait for the second album. Like “Eddie”: I really wanted to put that one on the second album, because I felt like it might be kind of a crowd pleaser. And we didn’t want the first album to be all the best stuff and the second one to be the leftovers. So there were certain songs that, even though other people wanted to mix them, I said, “Let’s save that one.”

Now that the two records are out, do you notice certain defining characteristics of each one?

Before we started mixing Unlimited Love and Return of the Dream Canteen, the band had the basic idea that we would try to cover the essential bases with the first record, and the second record would be the more eccentric, adventurous one.

There’s a certain feeling of relaxedness and looseness that distinguishes 'Return of the Dream Canteen' from 'Unlimited Love'

John Frusciante

But in several cases we contradicted this by saving certain staples for record two and putting some of the more unexpected things on record one. We decided in advance what the first and last song would be on each record, but the rest we figured out as we went along.

As it turned out, I hear Return of the Dream Canteen as a more fun record, and I think it goes to further extremes. This one has a more colorful, kind of “bright” thing to it. Not that it doesn’t have dark sections. But to me, Unlimited Love seems darker.

The new one also maybe has more surprising elements. There’s a little bit of that on the first album, too, but especially on the second half of this one, there’s probably more synthesizers and drum machines and stuff like that than people might expect from us. And it also feels more off the cuff and spontaneous.

There’s a certain feeling of relaxedness and looseness that distinguishes Return of the Dream Canteen from Unlimited Love.

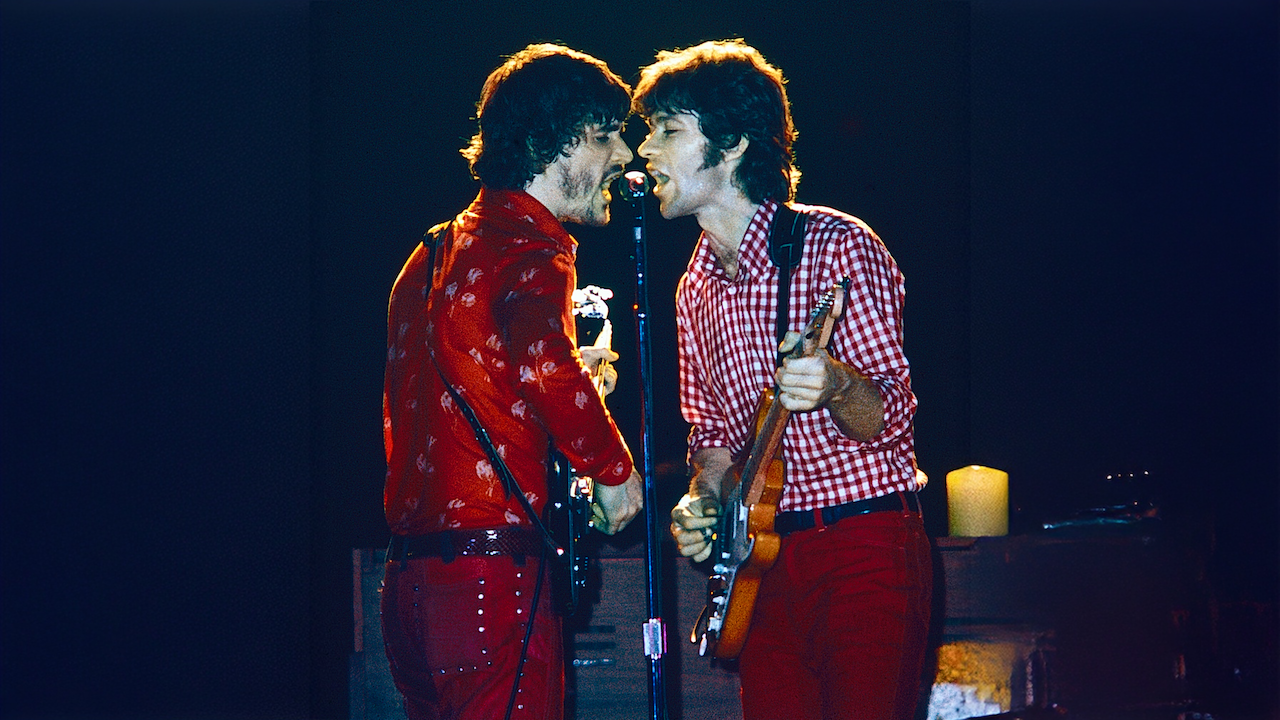

You mentioned the Return of the Dream Canteen song “Eddie,” which is clearly a tribute to Eddie Van Halen, especially in regard to Anthony’s lyrics. While the music doesn’t much reflect the Van Halen sound, you incorporated some overt EVH flourishes into your solo – tapping, whammy-bar work, unique phrasings. What was your intention going into that one?

When we’re in the studio and between takes, I’m always doing things, like two-handed tapping

John Frusciante

When we’re in the studio and between takes, I’m always doing things, like two-handed tapping. The engineers hear it all the time; I’ll play really flashy stuff during breaks. But when it comes to recording, I’m doing what I think is right for the song, and in most cases that doesn’t involve playing really flashy. But it is something I enjoy.

Still, doing that solo was a mind fuck, I’ll tell you that. And it was the last solo that I did out of all the solos on the 48 songs we recorded. I saved it for last, because the idea of having a song about Eddie Van Halen, you’re basically saying to people, “Think about Eddie Van Halen.” And then when it comes to this long guitar solo at the end, you’re going, “Now watch this!” And I did not like that idea.

I was even thinking of cutting the solo entirely, because I did not know how to go about it. I was trying for a while, and I wasn’t happy with anything I was doing. I was either going too far in the Eddie Van Halen direction, to where it was too busy and there was too much two-handed tapping and it didn’t sound like me, or I was just doing it and it only sounded like me… in a song about Eddie Van Halen.

How did you find a happy medium?

I just turned my mind off and stopped thinking about it. I stopped being self-conscious about the idea that the song was about Eddie Van Halen and just did what was natural. We were recording, and I took maybe a 15-minute break. And when I came back in, I just did the whole thing, like I said, in one take.

Whatever Eddie Van Halen is in there, it’s just there because of my love for him and the love that I’ve felt for his playing since I was eight years old

John Frusciante

Whatever Eddie Van Halen is in there, it’s just there because of my love for him and the love that I’ve felt for his playing since I was eight years old – things like the fast tapping and accentuating different notes with the vibrato bar. He did that a lot.

And then there are also the parts of his style that don’t involve playing fast, that are just really exciting to me – playing in a way that feels spontaneous, or when you hear feedback because he recorded his parts in the same room as his amplifier.

To this day, those things give me chills. Like, this is real, what’s happening here. This isn’t some guy standing in the control room punching in. This is a guy going out on a limb and taking risks. Throughout both of these albums, I tried to do a lot of that.

As far as the hallmarks of your style, one thing that has always stuck out to me is your use of space. You hear it on songs like “Eddie” and “Shoot Me a Smile” on the new album, and also in some of the band’s classic tracks, like “Scar Tissue” as well as “Californication.” Another obvious one would be “Otherside,” where, for much of the rhythm track, you’re playing maybe two or three notes. Where does that approach come from?

It really comes from trying to figure out what I can do that makes Flea and Chad sound as good as they can. Back in the time of Mother’s Milk, I was trying to fill up more space and it just sounded too busy.

It wasn’t as busy as Flea, but Flea has a way of being busy on the bass that never sounds too busy. It always sounds like he’s doing what he’s doing in support of the song. I felt after making that record that I wasn’t supporting the songs and my bandmates as well as I could have.

That began to change on the follow-up, Blood Sugar Sex Magik.

Another thing there was that Rick Rubin, when he started producing us at the Blood Sugar time, he kept adding ideas to the arrangements. Like, “Have no guitar for the first verse,” or, “Have no bass for the second verse.”

I was already going in the direction of playing less and seeing how much better that made the band sound as a whole

John Frusciante

He came from this hip-hop experience, so he was essentially muting the instruments in certain sections. That was inspiring for me, because I was already going in the direction of playing less and seeing how much better that made the band sound as a whole.

So I just got to a point where I really saw the musical value of space of all types, whether it’s the distance between one point in the bar line and another point in the bar line, or the distance between two sounds, in terms of using wide intervals or creating a chord out of me playing one note on my guitar and Flea playing one note on his bass.

It just seemed to make the band feel more whole. And to be honest, the other guys liked it when I started playing that way, and I felt supported.

You also employ intervals, and particularly wide intervals, in a very unique way.

I think a lot of people play guitar a certain way, and it may be because they’re just playing with bass players who play simple root-note bass lines. But because Flea plays in such an interesting way, I think of intervals not only as the relationship between two notes on my instrument but as the relationship between what I’m doing and what he’s doing.

If Flea’s playing a note and I’m playing a note, we’ve got a two-note chord right there

John Frusciante

Take something like the intro to “By the Way” or the verses of “Otherside”: I’m not thinking of my guitar as the center of it; I’m thinking of my guitar as a portion of it. I’m thinking of the pitch of Flea’s bass line and the pitch of my guitar.

If Flea’s playing a note and I’m playing a note, we’ve got a two-note chord right there. And the interval is the space between that. So then it’s like, “How can I move in a way that’s different from how he’s moving?”

If he goes down, maybe I go up. And we start creating different little harmony things where we imply chords without either of us playing the whole chord, that kind of thing. Or there’s things like “Scar Tissue,” where I’m doing those wide, two-note intervals on my own, but I’m really thinking of it as two separate parts.

Sonically, your use of space is complemented by the fact that you’re incredibly comfortable incorporating fully clean tones into your rhythm and lead work.

For me, it’s really about being punchy. That’s more important than distortion. Distorted guitar often sounds pretty wimpy to me. Even if the person’s got a rich, thick tone, if the way they’re hitting the instrument isn’t exciting and punchy, it doesn’t do anything for me.

A lot of the basis for my guitar playing, stylistically, is in music that I loved when I was a kid that I’ve always continued to love

John Frusciante

What inspired your attraction to clean tones?

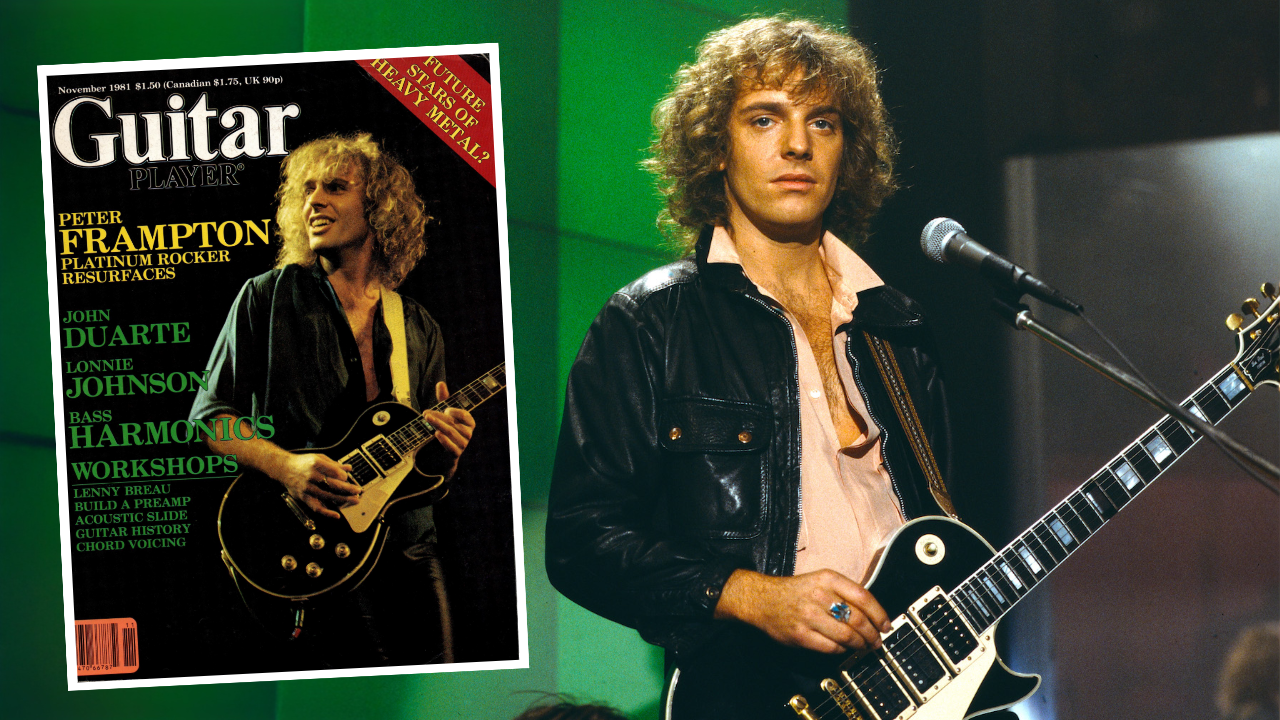

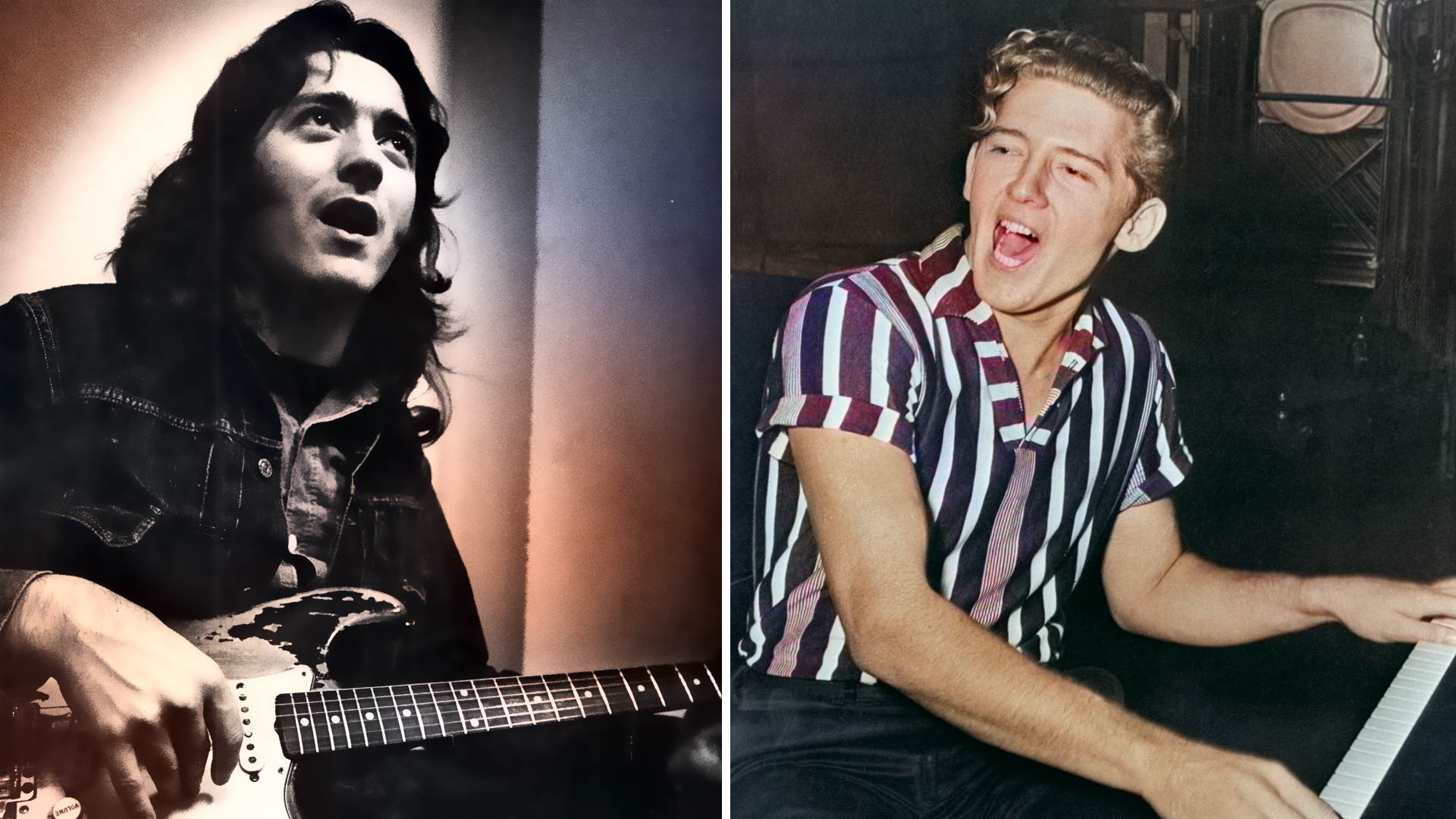

A lot of the basis for my guitar playing, stylistically, is in music that I loved when I was a kid that I’ve always continued to love. There’s a lot of post-punk stuff, or what we now call post-punk stuff. Back then we called it new wave.

But it’s guys like Ricky Wilson from the B-52’s and Matthew Ashman from Bow Wow Wow. Bands like the Cure and Scritti Politti and the Minutemen. The Pop Group is a really weird one, but I think they were some real originators, and the guitar playing is really good.

All these people and bands did really powerful things with clean tones. You listen to D. Boon’s playing in the Minutemen and you really hear what I’m talking about. He’ll rip into a solo, and the tone is clean as can be. But it’s got more power than a heavy-metal guitar player, just because he cares so much and he’s putting so much soul and feeling into the thing.

And Ricky Wilson, the first show I ever saw that was in a big place, like a 5,000-seater, was the B-52’s. This was in ’83. And his guitar playing was just incredible. Like, it made people happy. And I’m really about the emotional response.

For me, it’s more about reaching people than it is about wanting to say, “Look at how big and tough and macho I am.”

All that said, you can also conjure some truly thick and gnarly tones when the song calls for it. The chords you’re playing in the chorus of “Reach Out,” on the new album, would be a good example. Or, solo-wise, the fuzz-and-feedback frenzy in “The Heavy Wing,” on Unlimited Love. How did you achieve those sounds?

A lot of times it’s from using more than one distortion pedal at a time. I generally have a Boss distortion pedal on – the yellow [OD-3 OverDrive] or the orange [DS-1 Distortion] one – and also an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff or that brown MXR distortion pedal [the Super Badass Variac Fuzz].

I think the fact that almost all the distorted solos were done with me in the same room as the amp contributes to the tone in its own way

John Frusciante

It seemed like I used those a lot on the records. I can’t remember specifically what pedals I used where, but I’d say a lot of the time I’m combining different distortions and fuzz tones.

So it’s that, and then it’s also having the Marshalls really loud and being in the same room with them. Because even when you’re not getting feedback, when you’re right there in front of a loud amp, there is a form of feedback going on that contributes to the sense of the sound being kind of super blown-out.

I think the fact that almost all the distorted solos were done with me in the same room as the amp contributes to the tone in its own way.

Even with all of this focus on technique and sound and gear, the crux of your guitar playing is in the emotional content. How do you manage to play from your heart rather than your brain?

Once I got to the point where I felt I could pretty much play whatever I wanted to learn, it was a very exciting period for me

John Frusciante

God, that’s a good question, and a hard one to answer. I feel like all that conflict took place in me between the ages of 14 and 18, and after that I learned the lesson. And luckily my brain was developing while I was learning that lesson. But during those years when I was learning it, I had all kinds of conflicts. But once I got to the point where I felt I could pretty much play whatever I wanted to learn, it was a very exciting period for me.

But there was also that question in my mind of “What is it that I have to say?” Because I was so in love with all these different people who made vastly different types of music, and guitar players who were also so different from one another. And it seemed to me that each one had their own little place in saying something that was different than what the other one was saying.

Even people who were kind of similar, like Randy Rhoads and Eddie Van Halen, to me they were saying completely different things. And so when I was a teenager, I would wonder about those things, like, “What is it that I have to say that’s different from anybody else?”

How did learning theory play into that?

My understanding of theory was a way for me to be able to analyze the things that I liked. So if I was playing along with, say, the guitar solo in “Something” by the Beatles, and there’s certain notes that [George Harrison] plays that make me go, “Wow, what the hell was he thinking? Why did he go from that note to that note? Why does it feel so good when he does it?” – I’m able to look at those notes in relationship to the chords and the intervals and so on and figure it out.

So for me, the purpose of knowing the theory is to have an understanding of why I’m feeling a particular emotion.

It’s interesting that you utilized theory as a means of tapping into your emotions. It’s sort of the opposite of how many people think about it, which is that a reliance on theory can result in a clinical and cold approach to the instrument.

A lot of the time people want to sound confident on their instrument. But to me, vulnerability is one of the most endearing things to hear in a piece of music

John Frusciante

Well, I think a lot of the time people want to sound confident on their instrument. But to me, vulnerability is one of the most endearing things to hear in a piece of music. And I realized it felt like I was giving more of myself if I was vulnerable on the instrument.

That ties into using the clean tones, to doing things that are understated, all these things. And I think that’s universal. As much as we admire confidence in people, we all know deep down that vulnerability is one of the hardest things to achieve.

And any little degree that you can allow yourself to be more vulnerable, with your friends or with your partner or with your playing, it’s one of the strongest things you can do.

I would say that’s a through-line in most of the guitarists you cited as influences in your youth.

As far as me having those thoughts when I was a kid about what do I have to say to people with my guitar playing, I feel like a lot of what I’ve wound up having to say has to do with vulnerability. It has to do with being supportive of other people, and also putting yourself out there in a way that’s scary sometimes.

It’s that thing where it feels like your heart’s too much out there and people could stomp on it, but also that you’re okay with that, you know?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

“I don’t hate it, but it doesn’t fill my soul in the way that you see some performers.” Pete Townshend says he doesn’t like being onstage, and would rather work alone

“Occasionally one comes my way, and I’m like, 'Yeah, that needs to happen.’ This was one of those cases.” Samantha Fish on the guitar that became the heart and soul of her new album, ‘Paper Doll’