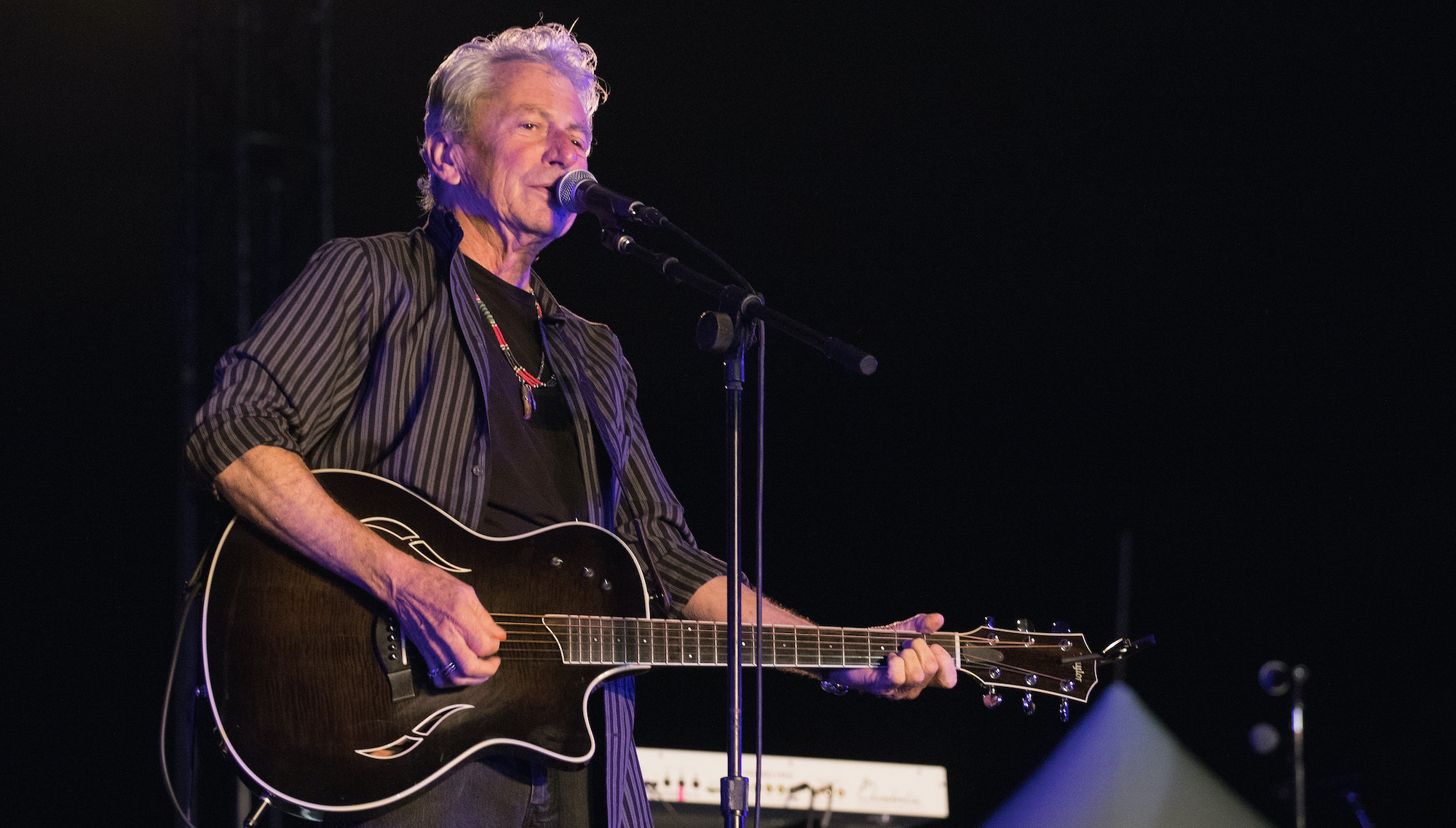

"A Lot of Times I’ll Write a Song Instead of Going to a Therapist. It’s Cheaper – and More Efficient": Joe Ely on the Five Songs That Have Defined His Career

From the greatest song Jerry Lee Lewis never wrote to a powerful tune that features Bruce Springsteen, these are some of the legendary singer/songwriter's finest recordings.

In a parallel universe, Joe Ely is a household name, filling stadiums and being lauded as a master storyteller shoulder to shoulder with Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. Both of those guys have doffed their metaphorical cap to the Texan’s unique ability to fit a short story’s worth of emotional depth and breadth into a three-minute song.

Ely’s take on that is simple: “I like to tell in a song where the location is, paint the background, and then bring it into a rhythmic world and try to find something that doesn’t take away from it, but adds to it,” he says.

When reminded that he once quipped, “I chase songs and I catch one of them every once in a while,” the Lubbock, Texas, native laughs. “I’ve got a whole bunch that I chased for many years but never caught,” he reflects. “Sometimes it’s like a stew or something: They can sit and simmer for many years until something might happen that lets you finish them.”

Ely started out on violin before he took to guitar. “I had been playing the violin since third grade,” he says. “But when I moved to Lubbock, the school didn’t have a music department, so I thought I’d just write my own music, and picked up the guitar.”

Lubbock’s most famous son is, of course, Buddy Holly, but Ely, who was just six days shy of 12 when the rock and roll pioneer died on February 3, 1959, grew up unaware that he hailed from his town. “He actually grew up about eight houses down from where I grew up,” Ely remarks, “but I only realized that years later when someone was telling me that Buddy grew up on 28th Street in Lubbock, and I thought, Hold on – that’s where I grew up! We could well have passed each other on the street.

"When I listened to some of those outtakes and rehearsals of his, I could hear that he was influenced by some of the same forces that I was, like Carl Perkins and Bo Diddley. All those different rhythms that he merged, with such simple and beautiful lyrics. I was just ripped apart when he was killed. He was so ahead of his time in so many ways.”

Having played country for years, Ely found himself on new musical turf when he became friends with the Clash in 1979. He opened up for the pioneering punk rock group on U.S and U.K. tours in the early 1980s, and introduced his unique flavor of rockabilly-fueled country to new wave audiences that had never heard anything like it before.

“When we played with the Clash, it was almost like a band of long-lost brothers, as we both fit into each other’s influences,” Ely says. “It was highly unusual, but it worked. I have a recording that was never released from a rehearsal at the Hope and Anchor, for our Live Shots album, recorded in London. It was just a really small pub, and some of the Clash came by and we recorded about seven songs together. It shows the point where the two bands collided.

"I still had a steel player and was very country-oriented in a way, but rhythmically, things kicked up a few notches.” That is perhaps an understatement. Musta Notta Gotta Lotta, his album from that time, released in 1981, is the hardest-rocking record in Ely’s catalog. The title track itself is the greatest song Jerry Lee Lewis never wrote.

Ely’s first album was issued in 1971, when he was part of the Flatlanders, with fellow Texans Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock. He’s continued to work with them, sporadically, over the years, most recently on 2021’s Treasure of Love. “That’s an album where we’re mainly covering the songs that influenced us growing up,” he reveals.

Ely’s last album under his own name was 2020’s Love in the Midst of Mayhem. “I woke up one morning and the world had changed with the pandemic,” he explains. “I started digging back and finding a bunch of old love songs of mine that I hadn’t recorded, that I thought would help people feel better through the pandemic. I know a lot of people were flipping out about what was going on in the world.”

Ely has been releasing his music on his own label, Rack ’Em Records, since 2007, and has plenty of projects in the pipeline, including a previously unreleased live recording with one-time Rolling Stones sax player, the late Bobby Keys.

“I always felt like I wasn’t free to work at my own pace,” he explains of the decision to found the label. “It took so long for the label and the publishing to come together, and I found that it was easier to do it myself. I could work a lot better at my pace, without a record company holding a magnifying glass to everything. It gives me a lot of freedom, and I can put out things on my label that might not have a home elsewhere.”

There’s plenty coming up in Ely’s future. Universal is set to reissue his first three albums for MCA as a box set in 2023, and he’s releasing a book of lyrics as well as a sequel to his first novel, Reverb: An Odyssey. “That book was pretty much autobiographical, although I did change a number of things for the sake of the story,” he says. And, of course, he continues to write songs.

“Times and friends change, and the world is always changing, so there’s always something to write a song about,” he says. As for his Five Songs selections, he explains, “Picking five was very difficult, but it gave me a chance to review different areas of my songwriting and see how it’s changed over the years.”

“Musta Notta Gotta Lotta” – 'Musta Notta Gotta Lotta' (1981)

“This one came at a time when I was going through some changes in my music. We were touring the U.K. with the Clash, about 1979, and it was almost like their songs and mine were being influenced by the same forces. My love of rock and roll was a big part of that.

"Lyrically, the songs I was working on changed; I rediscovered my rockabilly roots. I think it was actually good timing for the rockabilly side of me to come out, particularly in the U.K., which had a very strong rockabilly and traditional rock and roll scene. They never abandoned that music, as we did in the States for a while. You can see that from how the Stray Cats did so well over there before they broke through here. There were changes going on with the Clash as well.

"There is some great soloing on this from Jesse Taylor, and from Lloyd Maines on steel guitar. Those guys combined everything they knew and put it into that band. When the Clash came to the U.S., I showed them around Texas – San Antonio, the Alamo, and places like that. They’d previously shown us around all the interesting places in London. I remember that as a really great time.”

"All Just To Get To You” – 'Letter To Laredo' (1995)

"Bruce Springsteen sings backing vocals on this, and I really like the way our voices work together on those parts. We were doing a benefit together – he’d asked me to be a part of it – and that was the start of a really long friendship that I’ve had with him. He’s a great guy to hang out with, and I really like his way of painting characters and their backgrounds. He tells a great story.

"We started to play quite a lot of shows together. I really like to work with other people and see their take on a song and how they develop it. I’ve been going through old boxes of notes from the road and finding little pieces of songs – just the first things I’d written for them when they were just coming to life. It’s been very interesting.

"This is one of those songs that I remember writing and thinking it was taking the listener on a journey. I like to find a way to draw the listener in, maybe make them wonder where things are going to go and perhaps even surprise them with how things might turn out. Songs are multidimensional; you can go backward and forward in time.”

“The Highway Is My Home" – 'Satisfied At Last' (2011)

“This song is unusual for me, as the organ is the dominant sound on this track. This whole album moved into a different direction for me, after touring with different songwriters that I really liked, a lot of whom were from the rock world – guys like Tom Petty. We shared a love of the old-style rock and roll and rockabilly from the 1950s and how it turned into country rock in the 1980s.

"Now the borders between genres are so blurred that I don’t know what kind of descriptions to apply to a lot of what I hear. That’s good though, because it opens up doors for different ideas, and that’s kinda been my motto: Anything goes. I don’t like to paint myself into a corner where there are too many rules.

"Songs like this are an example of that, I think, where the organ sound deviates from what someone would expect to hear on one of my records. I picked this because it’s an interesting take on where I am now. I’ve been on the road my whole life, and this song really reflects the life of a traveling, working musician, I guess. I have no regrets though, I’ve made mistakes, but so has everyone. I try to turn mine into songs. That’s my psychotherapy.” [laughs]

"You Can Bet I’m Gone” – 'Satisfied At Last' (2011)

“This was a song that I wrote when I was having a hard time with my personal life, and it helped me straighten out. A lot of times I’ll write a song instead of going to a therapist. [laughs] It’s cheaper – and more efficient.

"I like the lyrics to this one a lot. I found the line ‘This old world is a funny place, you’re always running the same old race’ when I was going through my boxes of notes. The line, ‘You can measure your riches by the ones you love’ is something I very strongly believe to be true.

“I don’t hear a lot of real country anymore on the radio. It’s getting more and more pop every day. A song like this would have a hard time getting played on modern country radio. It seems like we’re forgetting what it is that makes great country music – not just a lyric that tells a story but a musical setting that doesn’t pander to modern rock and pop fashions and trends.”

“Indian Cowboy”

“I’d been in New York for a few months, freezing to death playing the folk clubs and walking the streets. I came back to Lubbock, my home at the time, and ran into Guy Clark. I remember playing this song for him, saying that I wrote it when I used to work at a circus. I joined Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, taking care of the llamas and the world’s smallest horse. He didn’t believe me. [laughs]

"I was only with them for about two months, traveling through Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. It was a great time. I was actually a big fan of the circus, because it was such a colorful folksy place, with wild stories that I could use later in my life for song ideas.

"I chose this song because it was from a time in my life when my writing changed. It had been influenced by folk music before it merged into the storytelling phase of my life. I used to jump freight trains when I was a kid; my father worked on the Rock Island railroad. I quit school when I was about 17, I guess, and I went out into the world.

"I’ve been looking through my old notebooks, reading stories that I wrote while I was on the road. That experience was a turning point to open up different parts of a song.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands

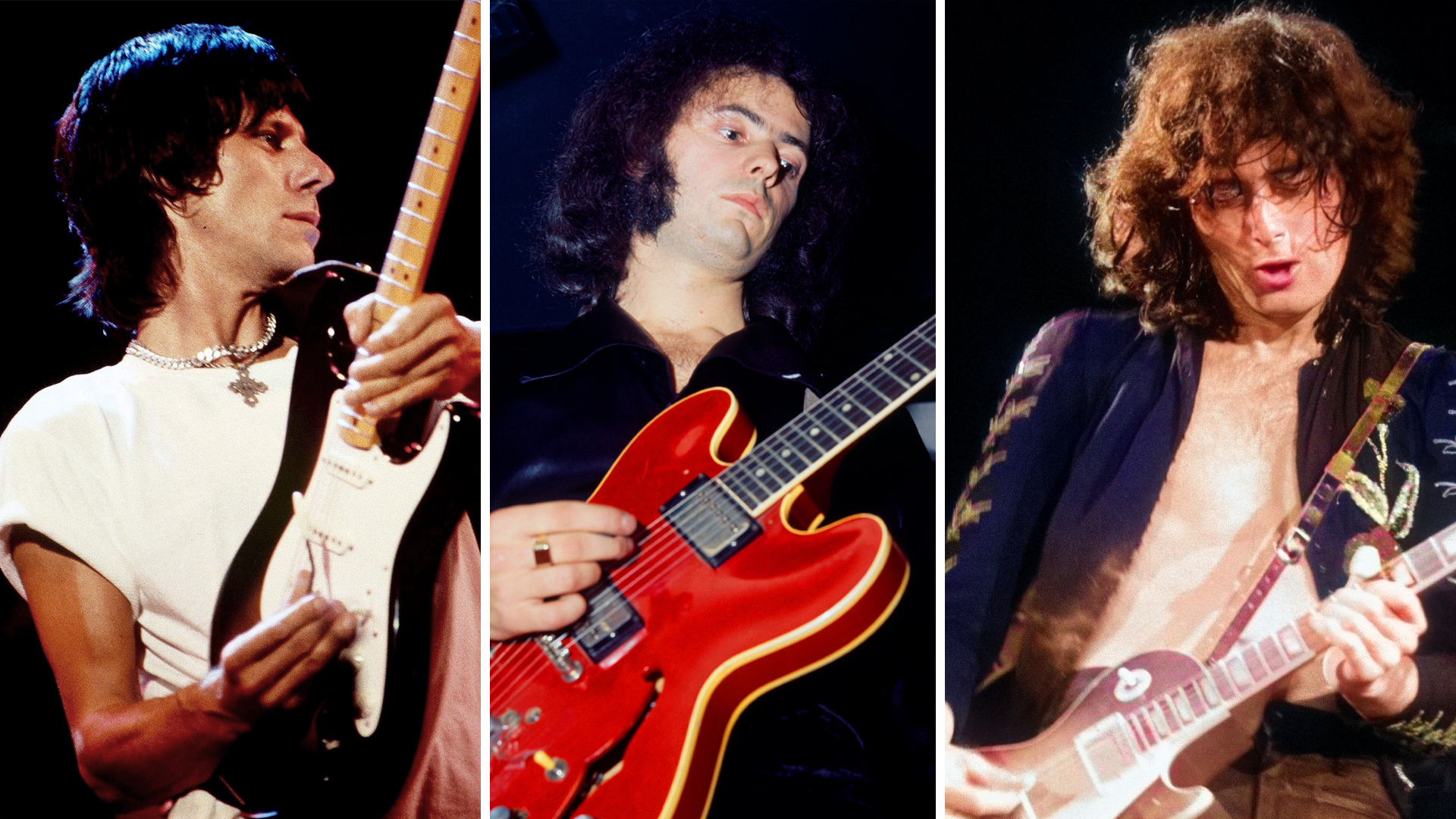

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue