53 Unsung Guitar Greats Every Player Should Know

53 underrated guitar players you need to hear.

It’s no secret that the talent, technique, and creative force of magnificent and awe-inspiring guitarists runs deep. And going deep doesn’t mean studying only the obvious guitar heroes. You have to get out on the fringes, and experience not only the players who influenced the greats, but also the seminal movers and shakers who were not blessed with massive or on-going pop-culture fame. After all, a complete guitarist is a vessel of multiple influences.

To this end, the GP staff endeavored to compile a vast list of players who float just under the popular radar. Of course, all such efforts are compromised by omissions, so to make sure our 101 list was as comprehensive as possible, we enlisted the input of players from the Guitar Player and Harmony Central forums. All of their suggestions were incorporated into the GP staff’s master list, and then began the vicious battle to whittle down the multitude to a workable number. We kept the “forgotten or unsung” criteria at the forefront of all challenges, but that doesn’t mean even we are confident every deserving player made the cut.

But whether you agree with some of the selections or not, what you’ve got is a colossal collection of fabulous guitarists worthy of your attention. Hopefully, you’ll be intrigued by some of these entries to seek more information about the artists, and absorb their creative concepts and licks into your own style. Above all, helping our readers increase the depth and diversity of their approach to the guitar was the GP staff’s main goal in this undertaking. Enjoy!

Junior Barnard

Of all the amazing guitarists to go through Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys, Barnard’s tonal audacity stands out. His solos on Wills’ “Brain Cloudy Blues” and “Fat Boy Rag” are jazzy, distorted wonders—and this is in the ’40s! Barnard was killed in a 1951 car crash at just 30 years old. “Junior was playing rock and roll years before it had a name,” his brother, Gene, told GP in 1983. —Darrin Fox

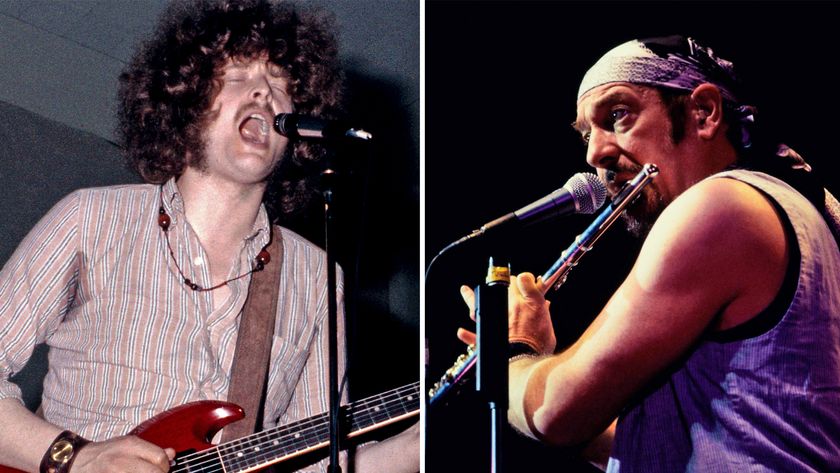

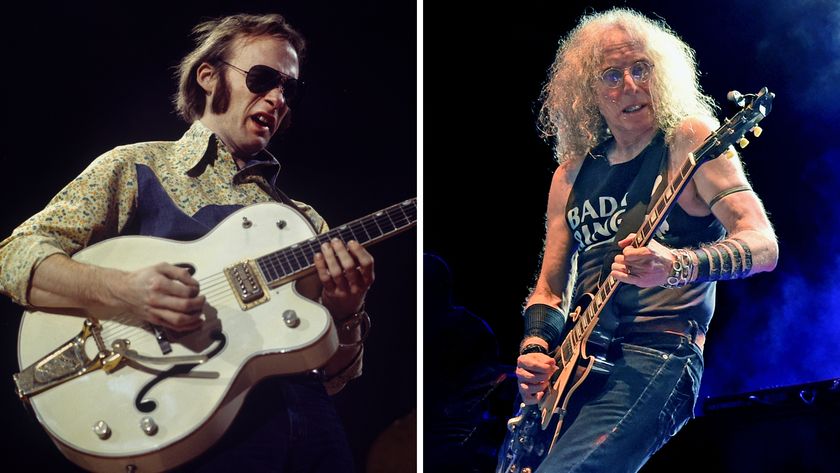

Jan Akkerman

European guitarists in the ’60s and ’70s were often influenced as much by classical, jazz, and gypsy swing as they were by blues and rock and roll. That was definitely the case with Dutch virtuoso Akkerman, whose thrilling performance on Focus’ classic instrumental “Hocus Pocus” (Moving Waves, 1971)—as well as his signature sounds crafted by a volume pedal, a Colorsound treble booster, and multiple Cordovox rotating speakers—brought him to the attention of American listeners. —Barry Cleveland

Davie Allan

Throughout the 1960s, the garage/surf instrumentals of Davie Allan and the Arrows set the pace for scads of motorcycle-gang films. Inspired by Duane Eddy, Nokie Edwards, and Link Wray, Allan created his signature fuzz sound on the song “Blues Theme,” which director Roger Corman used for his 1967 film, The Wild Angels. It turned into a single, and, by the end of the decade, Allan’s guitar work could be heard on dozens of B (for “biker”) movie soundtracks. —Art Thompson

Scotty Anderson

“It was quite possibly the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen,” Eric Johnson said of watching Cincinnati Tele ninja Scotty Anderson perform. Chet Atkins once told Anderson, “Each time I hear you play, I learn something.” But Anderson must be the Stealth Bomber of guitar, because, although as dangerous as Hank Garland, Merle Travis, and Jimmy Bryant all rolled into one, he hasn’t made much of a blip on radar screens. —Jude Gold

Mickey Baker

Known for his ’50s session work with Ray Charles, Ruth Brown, Big Joe Turner, and tons of others, Baker also authored several guitar instruction books. Baker’s biggest claim to fame is the duo Mickey & Sylvia, whose 1957 hit, “Love Is Strange,” prominently features his squawking, single-note lines. “I figured if Les Paul and Mary Ford could make money doing that nonsense of theirs, I could, too,” Baker told GP in 1976. —Darrin Fox

Robbie Blunt

During the ’80s, when shred and spandex metal were filling the airwaves with symphonies of distortion, Blunt’s crystalline Strat tones and vibey single-note phrases were more than a breath of fresh air—they were mysterious, magical, and sensual. His stunning performances on Robert Plant’s solo albums—particularly “Big Log” and “In the Mood” from 1983’s The Principle of Moments—pretty much established the singer’s post-Zeppelin sonic identity. —Michael Molenda

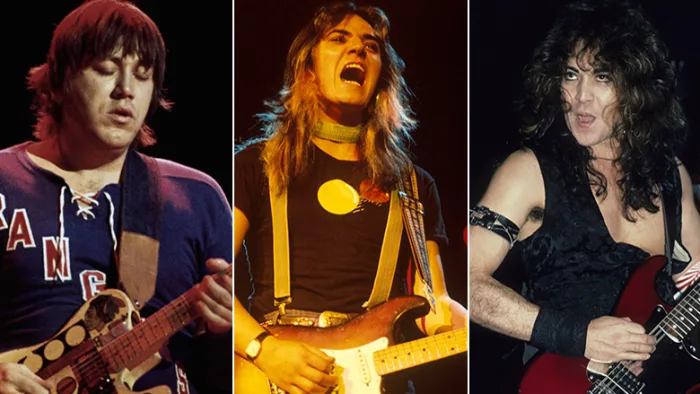

Tommy Bolin

A transcendent, yet erratic and troubled artist, Bolin (1951-1976) personifies the myth of the glorious flame that burns out much too soon. Despite immense talent and numerous chances for widespread fame—he played on Billy Cobham’s Spectrum, replaced Joe Walsh in the James Gang and Ritchie Blackmore in Deep Purple, and released two solo albums—Bolin succumbed to his addictions at just 25 years old. To get a sense of what his loss means to the guitar community, seek out The Ultimate: The Best of Tommy Bolin. —Michael Molenda

Lenny Breau

Once hailed by Chet Atkins as “the greatest guitar player in the world today,” Breau (1941-1984) brilliantly blended bebop and flamenco techniques with Atkins’ country thumbpick/fingerstyle approach by his early 20s. He went on to develop an astonishing 7-string style (on custom Dauphin acoustic and Kirk Sand electric instruments with high A strings) that allowed him to play bass lines and chords with his thumb and first two fingers while superimposing single-note lines with his third and fourth fingers, and often augmented with mind-bending octave harmonic arpeggios. —Barry Cleveland

Erik Brann

A prodigy violinist at the age of four, Brann brought a formal sense of melody, a wicked vibrato, and an uncanny mastery of effects to Iron Butterfly—the band he joined at age 16. Playing a Mosrite through either a Vox Super Beatle or a Marshall stack—and aided by an Echoplex, a spring reverb, and Mosrite Fuzzrite and Vox Wah-Wah pedals (given to him by Hendrix and Beck, respectively)—Brann’s style fused bits of Baroque and jazz with psychedelia, as evidenced throughout the albums In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida and Ball. —Barry Cleveland

Michael Bruce/Glen Buxton

As the twin-guitar dervishes of the classic Alice Cooper band lineup, Bruce and Buxton (1947-1997) fired off some of heavy rock’s most flamboyant riffs. Bruce was perhaps the group’s most prolific writer, but Buxton’s snotty and rebellious licks drove songs such as “School’s Out,” “I’m Eighteen,” and “Muscle of Love” straight into the fertile psyches of ’70s teenhood. The duo’s interlocking riffs, rhythmic interplay, and aggro tones set a standard that is, sadly, seldom matched today. —Michael Molenda

Randy California

Randy Wolfe (1951-1997) received instruction from traditional bluesmen as a child, and gigged with the early Hendrix outfit Jimmy James & the Blue Flames in 1966 at age 15, adopting the name “California” at Hendrix’s suggestion. By the time he co-founded Spirit in 1967, he had developed a unique style centered on super-sustained solo tones. Although primarily a Strat and Marshall man, early photos show California wielding Danelectro, Dan Armstrong, and Les Paul guitars, and playing through Acoustic amps. —Barry Cleveland

Danny Cedrone

Even in these post-Van Halen, post-Yngwie, post-everything times, Cedrone’s solo on Bill Haley and the Comets’ 1955 hit “Rock Around the Clock” is still a jaw-dropper. Cedrone—a Philadelphia session guitarist who used a 1946 Gibson ES-300 and a 1x12 Gibson BR-1 combo for the legendary track—opens with a furiously picked line, then suddenly works in some tangy half-step bends and slick, jazzy phrases, and caps it off with an insanely fast chromatic flurry that encompasses all six strings. Cedrone was paid $21 for the solo, and a little over two months later, died after falling down a staircase. He never knew the impact his solo had on the world. —Darrin Fox

Roy Clark

Before he was a cornpone joke dispenser on Hee-Haw, Clark was known as a super-clean picker with a boatload of technical facility (he won two National Banjo Championships as a teenager). Clark did time with country/rockabilly queen Wanda Jackson (that’s his guitar on her hit, “Let’s Have a Party”), before he cut his 1963 instrumental album, The Lightning Fingers of Roy Clark. His 1995 album, Roy Clark & Joe Pass Play Hank Williams, proved Clark can also hang in jazz circles. —Darrin Fox

Larry Collins

The sight of a pre-teen Collins playing the sh*t out of a doubleneck Mosrite must have been quite a sight in the ’50s, because it’s still unreal to see it on DVD in 2007! An understudy of Joe Maphis, and churning out some of the baddest rockabilly ever with his sister Lorrie as the Collins Kids, little Larry was a bona fide guitar star. His performances on the Town Hall Party DVDs will make you a believer. —Darrin Fox

Hank Garland

Other than Garland, there aren’t many guitarists who can boast credits with Elvis Presley (“Little Sister”) and jam sessions with Charlie Parker. Garland’s signature tune, “Sugarfoot Rag,” was cut when he was just 16, and he quickly ascended to royalty status in Nashville session circles. But Garland was also an accomplished jazz guitarist whose 1961 album, Jazz Winds From a New Direction, is a must have. Garland is also the “land” in the Gibson Byrdland—a guitar he designed with fellow guitarist Billy Byrd. —Darrin Fox

Greg Ginn

The amount of brutality Black Flag founder Ginn conjured from a Dan Armstrong Plexi guitar and a solid-state amp rivaled that of the L.A.P.D.—who would shut down the group’s shows, beating the local punks in the process. Ginn’s style stands apart from his punk contemporaries with its chordal savageness, and an improvisational, metal-edged, free-jazz approach to soloing that owes more to Ornette Coleman than Steve Jones. —Darrin Fox

Guthrie Govan

One of the more frightening shredders to ever come out of the United Kingdom—and we’re talking Holdsworth and Shawn Lane level chops, here—Govan is not only technically brilliant, but supremely musical. His solo debut, Erotic Cakes, established him as a highly lyrical player with a knack for couching his playing in interesting, harmonically advanced compositions that veer in and out of fusion, prog, and even pop. —Darrin Fox

Davy Graham

Often cited as the cat who popularized DADGAD tuning (he claims he invented it), Graham is also credited as one of the first acoustic fingerstyle players to incorporate blues, folk, Moroccan, and Indian elements into their oeuvre. Graham’s 1962 homage to his then girlfriend, “Anji,” is a litmus test for any budding fingerstyle guitarist, and the legendary Bert Jansch said of Graham, “He’s the single most influential person on everything I’ve ever done.” —Darrin Fox

Guitar Slim

He paid hookers by the week, drank mineral oil to “lubricate” his voice, dyed his hair blue, and performed with a 150' guitar cable in the ’50s—often while riding on the shoulders of Johnny “Guitar” Watson. Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones (1926-1959) lived fast and died young, but formed a distinctive style of New Orleans blues guitar by playing twisted melodic licks and driving his goldtop Les Paul to previously unheard levels of distortion. —Dave Rubin

Ollie Halsall

Although Halsall’s most famous work is on the ultimate Beatles send-up, the Rutles, the British underground legend was also capable of expansive improvisations, unparalleled musicality, and blinding technique. “His playing on the first two Patto albums is it,” says XTC’s Andy Partridge of Halsall’s early ’70s fusion outfit. “His solos would explode into the ionosphere like a John Coltrane improvisation.” Halsall died in 1992, at the age of 43. —Darrin Fox

Bill Harkleroad

More famously known as Zoot Horn Rollo, Harkleroad’s jarring, future-blues as a member of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band still resonates, 30-plus years on. Harkleroad—who used metal fingerpicks to get as harsh a tone as possible at the Captain’s request—was often tasked with arranging Beefheart’s tapes of spontaneous piano musings and whistling into actual tunes. “Beefheart didn’t teach me how to play guitar,” Harkleroad told the BBC in 1997, “but he influenced how I play guitar more than anybody.” —Darrin Fox

Steve Hillage

Hillage’s take on psychedelia had its origins in British blues and England’s late-’60s/early-’70s Canterbury scene, where he performed with groups such as Gong, before initiating a multifaceted solo career. Early recordings featured phase-shifted, Leslie-fied, tremolo-ed, and otherwise swirling Strat tones, further processed through tape echoes, filters, and anything else that produced spacey sounds—though his fiery and formidable solo chops were anything but ambient. Tune into Gong’s Angel’s Egg (1973), and Hillage’s Green (1978). —Barry Cleveland

Lonnie Johnson/Eddie Lang

It’s only slight hyperbole to say that blues guitar begins with Alonzo “Lonnie” Johnson (1899-1970), and that jazz guitar starts with Salvatore “Eddie Lang” Massaro (1902-1933). B.B. King called Johnson “the most influential guitarist of the 20th Century” for his pioneering single-string improvisations in the 1920s, while Lang invented sophisticated comping. As a duo—with Lang billed as “Blind Willie Dunn” due to racial segregation—they created blues duets that still astonish, as revealed on Blue Guitars, Vol. 1-2. —Dave Rubin

Terry Kath

A founding member of Chicago, Kath (1946-1978) injected hard-driving rhythms and spitfire solos into the band’s horn-driven sound. Inspired equally by jazz players such as Howard Roberts, and rockers such as Hendrix, Kath incorporated elements of both into his harmonically savvy approach. His main guitars in 1971 were a ’68 Stratocaster and a low-impedance ’69 Gibson Les Paul Professional, played through a 60-watt Allied Electronics Knight amp. —Barry Cleveland

Danny Kirwan

Peter Green tapped the 18-year-old Kirwan to join Fleetwood Mac in August 1968, thus creating an unstoppable, yet ultimately tragic British blues guitar tandem. Kirwan’s vibrato was wide and luxurious, and where Green’s playing could be sweet and tender, Kirwan raged with a hard attack and wild abandon. The Kirwan-penned “Something Inside of Me” is a haunting minor blues, and live versions of “Like It This Way” are incendiary. Kirwan stayed in the Mac after Green’s mental breakdown, but battled his own demons, and is only now getting his life back together. —Darrin Fox

Bill Kirchen

GP has termed him “A titan of the Telecaster,” and Kirchen’s work with Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen in the 1970s made him a cult hero to roots-oriented players, who reveled in his hot picking on such classic CC albums as Lost in the Ozone, Hot Licks, Cold Steel, & Truckers’ Favorites and Country Casanova. Since then, Kirchen has kept alive the guitar styles forged in Texas swing and Bakersfield honky-tonk via his twang-o-riffic solo releases. —Art Thompson

Roy Lanham

Although he replaced the hot-headed Jimmy Bryant on TV’s Hometown Jamboree in 1955, Lanham was a much different player than the fleet-fingered Bryant. Lanham flaunted a luxurious chord-melody style, and his mid- ’40s recordings with the Delmore Brothers foreshadowed rockabilly by a decade. He also appeared on Loretta Lynn’s 1960 hit “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” and even did some Monkees dates. For an excellent Lanham primer, get Sizzling Strings/The Fabulous Guitar. —Darrin Fox

Shawn Lane

A member of Black Oak Arkansas as a teen, and featured guitarist on Highwayman 2 with Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson, multi-instrumentalist Lane (1963-2003) did his most memorable work in collaboration with mega-bassist Jonas Hellborg, including 1995’s Abstract Logic, and 2000’s more ethereal Good People in Times of Evil, with Indian master percussionist V. Selvaganesh. Lane’s idiosyncratic fusion of rock, jazz, blues, and South Indian styles—impeccably executed at often-breakneck speeds—made him one of the most original and engaging guitarists ever. —Barry Cleveland

Jake E. Lee

Lee’s tenure with Ozzy Osbourne brought the singer back to respectability after the tragic death of Randy Rhoads. Straight out of the Southern California school of flashy rock gods—and with the look, attitude, and chops to back it up—Lee performed sacrilege by playing ’80s metal without using a whammy bar, making up for it with an abundance of neck wrangling, behind-the-nut bends, and awesome tuning-machine manipulations. —Darrin Fox

Lonnie Mack

With a style running deep in the blues, Lonnie Mack virtually invented blues rock with a Flying V and a Magnatone amp when he off-handedly cut a scalding, hit instrumental version of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis” in 1963. Stevie Ray might have played a lot slower without Mack’s example. —Dave Rubin

Magic Sam

Sam “Magic Sam” Maghett (1937-1969) pioneered the West Chicago style in the late 1950s, along with Otis Rush and Buddy Guy. His biting, heavily reverbed sound—as inspired by B.B. King—broke ranks with the country blues of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf to forge a proud new identity for young, urban black artists. Fingerpicking his licks on a Strat, Maghett had mastered the power trio format, and crossover success seemed imminent, when he died suddenly at 32. —Dave Rubin

Al McKay

McKay cut his teeth with the Ike & Tina Turner Review, but it was drop-dead, pinpoint-precision funk guitar with Earth, Wind & Fire that made him an R&B icon. Cutting the bulk of his classic EW&F tracks with a Telecaster, (which he modded with a neck-position humbucker after seeing Chicago’s Terry Kath), McKay is also a flashy soloist, as proven by his blazing break on “Shining Star.” —Darrin Fox

Memphis Minnie

Reputedly the first blues musician to don a strap and play standing—as well as one of the first to play electric guitar—Lizzie “Memphis Minnie” Douglas (1897-1973) also cut the heads of fellow Chicagoans Big Bill Broonzy and Tampa Red. In the ’30s and ’40s, she led electric blues combos using cool National guitars, years before Muddy Waters would change the paradigm in 1948. —Dave Rubin

June Millington

A kick-ass guitarist who can rage through hard rock, pop, country, folk, and blues, Millington is a true icon of women’s music. In 1970, her band Fanny was the first self-contained, all-female rock group signed to a major label. She has been a force for women’s artistry ever since, co-founding the Institute for the Musical Arts—an organization that educates and empowers female musicians—in 1986. GP once called her “one of the hottest female guitarists in the industry,” but she deserved to have “female” removed from the sentence. —Michael Molenda

Leo Nocentelli

Leo Nocentelli earned his crown as the king of New Orleans-style funk guitar during his groundbreaking work with the Meters. Nocentelli hallmarks include a crispy clean tone, creative use of chord fragments, and a laser-like execution of licks that were often doubled by the bass. This is different from James Brown’s funk, where the guitar rides a ninth chord over a heavy backbeat. The second-line rhythms indigenous to southern Louisiana are uniquely syncopated, and the real magic of the Meters lies in interlocking parts. The Nocentelli-penned instrumental “Cissy Strut” is a textbook example. —Jimmy Leslie

Jimmy Nolen

Unquestionably the godfather of funk guitar, Nolen’s sixteenth-note ninth-chord riff on James Brown’s 1965 hit “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” was the funkiest shot heard around the guitar world. Played on a Gibson ES-175 with a super-low action and .013-.056 gauge strings, Nolen created the style that every guitarist from John Frusciante to Nile Rodgers to a guy in a disco cover band must know. Nolen died of a heart attack at the age of 49 in 1983. —Darrin Fox

Mike Oldfield

Think “Mike Oldfield,” and 1973’s mega-platinum, pre-new-age Tubular Bells probably comes to mind. But Oldfield’s prowess as a highly innovative guitarist is often overlooked. For example, he created a singular overdriven sound by routing his mid-’50s Les Paul Junior through a convoluted signal chain that included a treble booster, a battery-powered Vox amp, a Teac reel-to-reel, and multiple graphic EQs, resulting in both super-mellow distortion and “feedback harmonics.” On his 1999 release, Guitars, Oldfield used the guitar as the source of all sounds—including percussion. —Barry Cleveland/Jimmy Leslie

Robert Quine

Quine broke out with NYC proto-punkers Richard Hell & the Voidoids, loading 1977’s Blank Generation with his frenzied-yet-sophisticated Stratocaster histrionics and ultra-edgy tone. Later, Quine joined Lou Reed’s band for The Blue Mask, Legendary Hearts, and Live in Italy, before splitting for sessions with Brian Eno and Tom Waits. He also played on Matthew Sweet’s seminal ’90s albums, and, sadly, took his own life in 2004. —Jimmy Leslie

Jerry Reed

Before the silver screen came calling, Reed was better known as an ace picker. With tunes such as “The Claw,” and “Jerry’s Breakdown,” Reed’s style drew liberally from Merle Travis and Chet Atkins, but bore his own funky charm with heavy doses of string popping and chicken picking. The Unbelievable Voice and Guitar of Jerry Reed and the two-for-one CD, Me and Jerry and Me and Chet, are essential listening. —Darrin Fox

Joseph Reinhardt

Being a guitarist and a sibling of Django Reinhardt had its advantages and disadvantages, but Joseph “Nin Nin” Reinhardt’s (1912-1982) aptitude for pounding out le pompe on his Selmer Grande Bouche provided both foundation and fuel for his legendary brother’s flights of fretboard fancy. Besides grounding Le Hot Club de France, Nin Nin was a fine bandleader and soloist, as you can hear on Joseph Reinhardt Live in Paris. —Barry Cleveland

Emily Remler

Influenced by Wes Montgomery, Remler became the most important female jazz guitarist of the 1980s. The title track of 1988’s East to Wes is an excellent homage, and a fine example of her use of thumb-strumming octaves to spice up melodic phrases. “Hot House” demonstrates how Remler’s fluid technique allowed her to burn hard bop solos with seamless execution of extended single-note runs. Unfortunately, she suffered a sudden heart attack in 1990, and died at age 32. —Jimmy Leslie

Jimmie Rivers

You know a guy is great when one album cements his legacy forever. In the case of Rivers, the album is Brisbane Bop—a collection of live recordings made during Rivers’ stint at the 23 Club in Brisbane, California. Rivers style was an amalgam of Jimmy Bryant and Barney Kessel, but he rolled it all into a spicy mix that was all his own. Armed with a doubleneck Gibson EDS-1275, Rivers sparring matches with steel savant Vance Terry are pure bliss. —Darrin Fox

Roy Rogers

Nope, this isn’t the cowboy who stuffed Trigger. This Rogers—an acoustic and electric stylist with roots in the Delta blues of Robert Johnson—slings a mean slide instead of a six gun, and he played with John Lee Hooker from 1982 to 1986 (appearing on the Boogieman’s Grammy-winning The Healer), before going solo. —Dave Rubin

Sabicas

Born Agustín Castellón Campos (1912-1990), the Spanish flamenco maestro started performing at six years old, and, after fleeing the Spanish Civil War in 1936, became one of the first players to introduce flamenco to audiences across the globe. His light-speed picados and arpeggios could humble a modern shredder, and he also had a beautiful tremolo and perfect pitch. He was a major influence on Paco de Lucía, who said, “In Sabicas, I saw a new way of playing.” —Mark C. Davis

Sonny Sharrock

Madman! Sharrock (1940-1994) may be classified as an avant-garde jazzer, but his frightening explosions of serrated noise and spastic note flurries—juxtaposed by moments of almost lullaby-like beauty—put him in a class by himself. Career highlights include an uncredited solo on Miles Davis’ A Tribute to Jack Johnson, a tenure in Last Exit, his solo-electric compositions on 1986’s Guitar, and his scores for the animated Space Ghost Coast to Coast just before his death. —Michael Molenda

T.K. Smith

Smith has lent his formidable 6-string swing to Big Sandy and the Fly-Rite Trio, the Bonebrake Syncopators, and his own group, the Smith’s Ranch Boys. Smith’s style harkens back to the days when western swing, rockabilly, and jazz intersected—all in the same solo! Dig Smith and steel player Jeremy Wakefield’s tribute to Jimmy Bryant and Speedy West on Deke Dickerson’s Guitar Geek Festival 2004 for a hearty taste of Smith’s talents, or check our guitarplayertv.com. —Darrin Fox

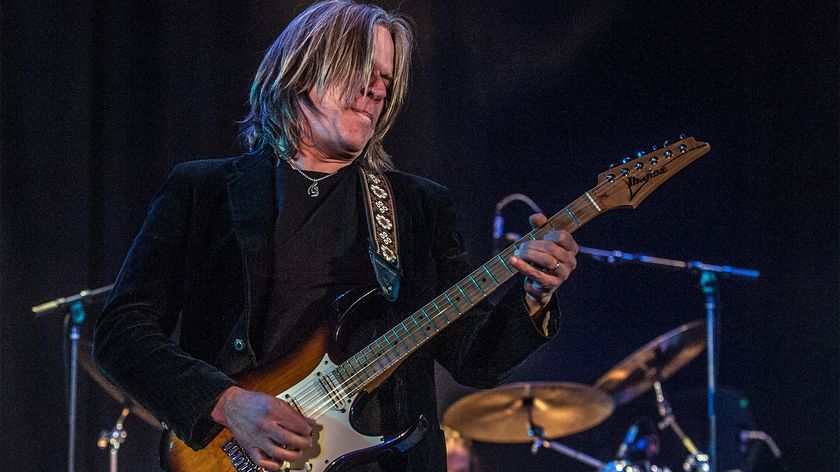

John Sykes

With a Les Paul Custom and a vibrato wider than the English Channel, Sykes burst out the new wave of British heavy metal in the late ’70s with the Tygers of Pan Tang. An amazing rhythm player and power riffer, Sykes also has tone and chops for days, whether playing with Thin Lizzy (1983’s Thunder and Lightning and reunion tours), Blue Murder, or Whitesnake (How about that lick in the “Still of the Night” fade out for some serious shred?). —Darrin Fox

Gabor Szabo

Born in Hungry, Szabo learned to play jazz by listening to partially jammed Voice of America radio broadcasts, and fled his native land in 1956, carrying only his guitar. He eventually established himself as an innovative player in America, winning Downbeat’s New Star Award in 1964. Szabo played an Ovation Glen Campbell acoustic amplified with a DeArmond 210 pickup, using a combination of fingers and an oddly held pick. His masterful-but-quirky style was augmented by one-string solos played entirely with feedback, and sitar-like effects created by scraping the strings with his pick’s edge. —Barry Cleveland

Tampa Red

Hudson “Tampa Red” Whitaker (1904-1981) was the first grandmaster of standard-tuned slide combined with conventional fretting. He was a mainstay of the Chicago blues scene in the 1930s, with Big Bill Broonzy and Memphis Minnie—although his hokum numbers such as “(Honey) It’s Tight Like That” sometimes overshadowed his virtuosity. You can hear Red’s vocal-like glissing in the styles of Robert Nighthawk and Earl Hooker. —Dave Rubin

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Rosetta Nubin Tharpe (1915-1973) was a flamboyant guitarist with a country and swing style that presaged Chuck Berry. Her lifestyle was as flashy as her playing—she was married at a ballpark, and played guitar from second base—and Tharpe traded gospel for blues in the 1950s. She eventually returned to the flock, but still wailed on Gibson electrics at speaker-frying levels. Check out Shout, Sister, Shout—a tribute album with a must-see video clip from 1960. —Dave Rubin

Clarence White

With a glut of Byrds reissues over the past few years, White’s honky-tonkin’ B-Bender approach is well represented. But what tends to get overlooked is White’s other legacy as a bluegrass flatpicker with the Kentucky Colonels in the late ’50s through the mid ’60s. The band’s Appalachian Swing! and 33 Acoustic Guitar Instrumentals are great places to delve into White’s pre-Byrds stylings. White was tragically killed by a drunk driver in 1973. He was just 29. —Darrin Fox

James Williamson

Williamson’s metallic, fuzzed-out pageant of violence on the Stooge’s 1973 swan song, Raw Power, is some of the scariest guitar playing ever laid to tape. Then, hoping to ignite a post-Stooges career, he and Iggy Pop tracked demos (later released as Kill City) rife with isolation, angst, and madness, and brilliantly punctuated by Williamson’s thuggishly cinematic guitars. Fast-forward a few years, and Williamson was out of music, evaporating into Silicon Valley’s corporate world. —Michael Molenda

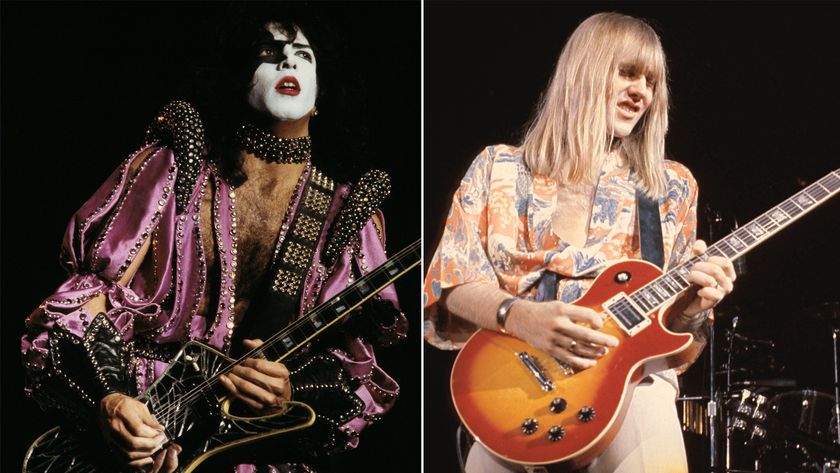

Roy Wood

Whether with the Move, early E.L.O, or Wizzard, Wood has been one of the U.K.’s most eccentric popsters. In the ’60s, Wood buttressed the Move’s tunes with tons of jangling electric 12-string, but also exploited devices such as de-tuned riffery on “Omnibus,” shards of whacked-out wah and baroque fingerpicking on “Cherry Blossom Clinic,” and outlandish, bluesy soloing on “Wild Tiger Woman.” Wood’s antics inspired diverse talents such as Johnny Ramone, Kiss, and psych-rockers Dungen. —Darrin Fox

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.

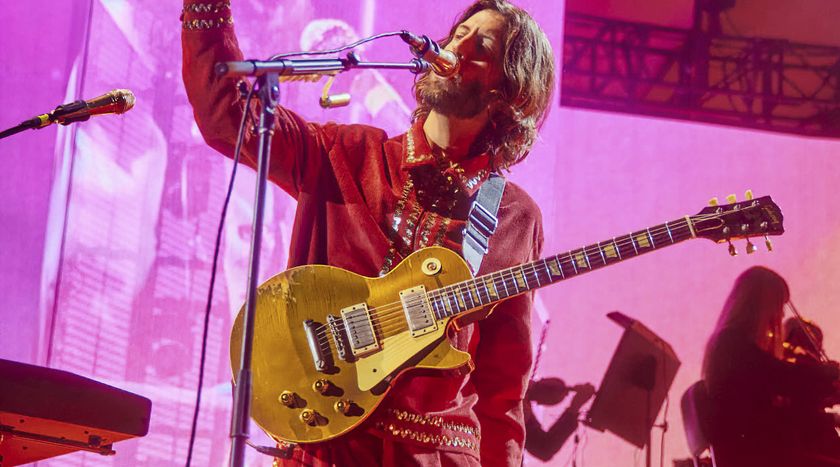

"Shane called me and said, 'The guitar is here. It plays amazing. It's providence calling!’” How an extremely rare goldtop 1958 Les Paul Standard found its way into the hands of Imagine Dragons guitarist Wayne Sermon

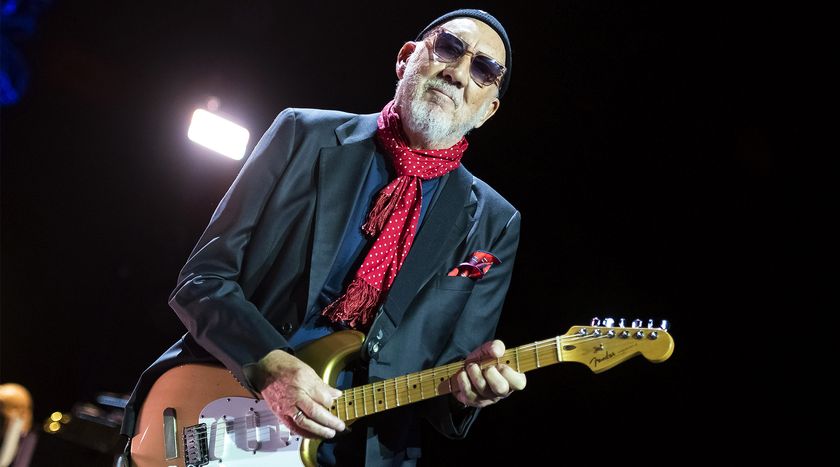

“A lot of Who fans would be really pleased.” Pete Townshend ponders using AI to re-create his ‘70s heyday for fans who prefer the Who's classic songs