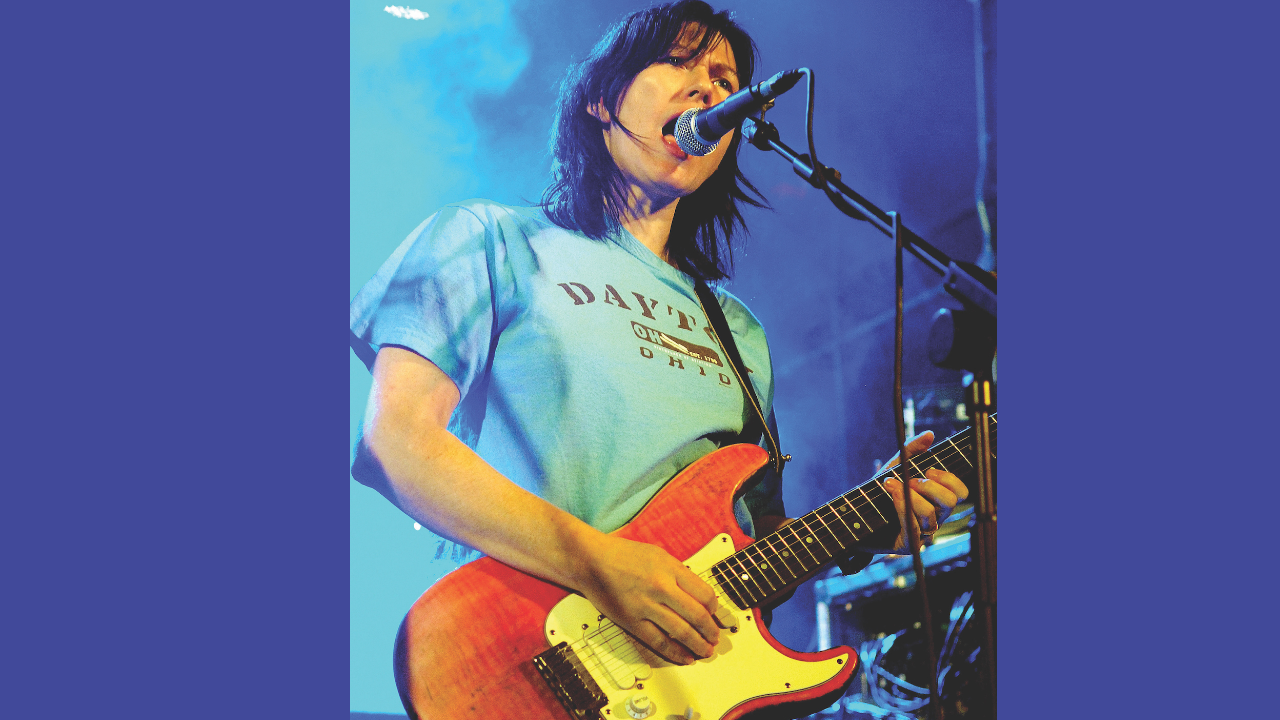

"We call it 'the claw': the hand shape you typically use on the neck. I change my tunings so that when I do the claw, it’s not something I would typically play.” Kelley Deal on the weird creativity of the Breeders' Last Splash

30 years on, The Breeders Kelley Deal reflects on the making of the 1990’s alt-rock masterpiece that propelled them to fame

When Pixies bassist Kim Deal asked her twin sister, Kelley, to join the Breeders, a side project that she had started with Tanya Donelly of Throwing Muses in 1989, Kelley was not particularly surprised. In fact, it was a reunion that was long overdue. “We grew up playing music together, so it seemed completely normal to me and her that she would have me involved,” Kelley says.

“Drums were my first instrument, and Kim and Charles [Pixies frontman Black Francis] actually split the ticket for me to go to Boston to be the drummer for the Pixies. I wasn’t an active drummer at that time, and when I heard the songs I was like, I can’t do that gig. They need a real drummer.”

Kim had also reached out to Kelley when the Breeders made the recordings for their first album, 1990’s Pod, with producer Steve Albini.

“She asked me if I wanted to go, but I couldn’t get off of work for it. I think I was working for Litton Computer Services, which is a defense contractor in Dayton, Ohio, where we’re from.”

When the Breeders were preparing to record 1992’s Safari EP, Kim once again approached Kelley about joining her in the band, and Kelley this time made the jump. “Kim asked me what I wanted to play; the choice was open. I didn’t say guitar, I didn’t say rhythm guitar, I didn’t say bass guitar. I said lead guitar. I wanted to play the star.”

The Breeders would tour extensively in 1992, including a slot at that year’s Redding Festival and a run supporting Nirvana, and would enter the studio in early 1993 to make their second full-length, Last Splash, with many of the songs already road tested and demoed. Still, Kelley was relatively new to the guitar and to the exigencies of the recording process.

“When we recorded Last Splash, every single person there — with the exception of our drummer, Jim Macpherson — could play guitar better than I could.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“At any time, they could have taken the instrument and been like, ’Okay, that’s fine. All right. Okay. Let me just do it real quick.’ They could have made the decision, ‘We don’t have the time or the patience.’ But they never did. And it makes all the difference, because then you have ownership over your parts and the record, and you feel proud about stuff.”

Released in August 1993, Last Splash would go Platinum on the strength of its hit single, “Cannonball,” but it is anything but a conventionally commercial album. An exercise in contrasts — where catchy riffs and sweet melodies are jostled by squealing guitars and other disquieting noises — it’s the rare album that somehow manages to sound as satisfying as it does strange. “It’s a really lovely art piece, and it seems like a complete thought,” Kelley says.

“And whenever I think about the record, I like to consider us an art band, because we do have weird sounds and weird moments and lots of empty spaces. A lot of the time, what you don’t play is more important than what you actually do play.”

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the album’s release, the Breeders have released a new deluxe edition of Last Splash and have been performing the record live in its entirety. Guitar Player caught up with Kelley Deal on the Breeders’ bus, just as the celebratory tour was getting underway.

Beyond it being very cool, was there a musical rationale behind your request to play lead guitar in the Breeders?

Yeah, Jimmy Page in [the 1976 concert film] The Song Remains the Same. That blew my little prosaic mind of what a lead guitar could be. It was soundscape — an art project.

Once you decided to be the lead guitarist, did you then develop a practice regimen?

Did I sit down and learn how to play scales? No. Had I done that, I would’ve obviously been a more proficient guitarist, but I would also have been a different guitarist. Even today, with what little I do know, I have to remind myself — especially on songs that we recorded back then, like “Hag” — not to do the little string-wiggle vibrato.

I have to just let that note lay there, and back off of it and keep that vulnerability and sincerity. It’s got to just be those notes, and then leave. My narrator is not a jammer.

The guitar is so physical and muscle-memory–based that once you develop patterns, it can completely limit you. Your hand is playing you.

You’ve got to really work at getting out of that. Even today, when I write or do anything for my other band, R. Ring, my partner in that, Mike Montgomery, often talks about “the claw” — the hand shape you typically use on the neck. It’s the same claw that you always make.

I’ll just change the tuning on my guitar so that when I do my claw, it produces different notes and sounds than if it was tuned in standard. Then it’s like, “Oh see, that’s not something I would typically play.”

In addition to Page, were you inspired by any other more alternative guitarists?

Andy Gill from Gang of Four, for sure, because that was another revelation for me. It was the anti-blues. It’s so easy to go into blues-based rock or blues-based lead playing, and I really try not to. And the tone was so different. It was so abrasive and ugly.

“Cannonball” was a huge hit song for the band. Was there any sense while you were recording the album that it had a special commercial potential?

We knew it was cool and stuff, but I don’t know if many people remember that at that time, on alternative radio or college radio, that was not what was being played. It was jangly stuff, like R.E.M. This was a very noisy, noisy track, and the arrangement is weird. Nothing repeats the same amount. The guitars stop, the drums stop. The lead guitar does not shred or do anything. It just does that hook. And the main guitar is a distorted acoustic. It was just a very weird track.

The sliding guitar hook on “Cannonball” must be challenging to play evenly and smoothly.

We actually had to tape some of the strings that I wasn’t using. To get that part loud enough and compressed enough, you can’t have any string dangle. It’s a dry, warm tone — a nice jazzy, George Benson kind of thing — and I played on the fifth fret of the D and the G. When we play the song live, I use a boost on that part, and I turn the reverb up a little. But that’s a tough one to get creamy enough versus just loud.

When listening closely to Last Splash, particularly on headphones, it’s noticeable how much attention is given to the “noise” elements of the record. They’re perfectly timed for dramatic effect. They pan, they mute. it’s really elaborate.

Every single note, squiggle and squeal has been curated for the listener. And I think what’s so great about the record is that it doesn’t sound like that. So much sounds accidental, and of course, some things were, but they were accidental and then left in. There was a lot of accidental stuff that was not left in too.

But the end result is that it doesn’t sound overworked; it sounds natural. It sounds like a bunch of people got in the studio and just did it. And that’s not it at all.

For the end of “New Year,” for example, I went out into the live room and just made all kinds of sounds — reverb, squeals, whines, moans — and then we put that to quarter-inch tape.

We fed the tape into the machine and then meticulously went through it: You hear a squeal, and then you mark it, and you write squeal. And then there’s a nice bit of feedback, and you write feedback. You keep doing that, and you isolate these sounds that are interesting.

Then we unloaded the tape, cut it, and made little piles of blips, feedback, whatever. Our co-producer, Mark Freegard, taped all that together, some of it backward, and that’s the piece that you hear.

What were the main guitars on the record?

Mainly my Strat Ultra, and then I used Kim’s goldtop Les Paul, because I didn’t have a Les Paul at that time. Kim also had her Strat and her acoustics. A lot of songs have acoustic run through distortion as the main rhythm guitar. We really didn’t have a deep pocket of guitars, but our engineer, Andy Taub at Coast in San Francisco, knew Chuck Prophet from [the Tucson-based alt-country/ neopsychedelic group] Green on Red, and he brought over a ton of equipment, like the mandolin I play on “Drivin’ on 9.” That really helped us.

And as far as amps and pedals go?

Kim and I used the Marshall JCM900s that we still use to this day. I love those so much. Every time I play something else, I just want to get back to my JCM900. I’m so happy about it because of the channel switching. It’s a workhorse, and it’s a beautiful pedal platform.

I also had this great Montgomery Ward amp that I found in a pawn shop. It has great tremolo on it, and that’s what you’re hearing any time there’s that effect on the record, like on Kim’s vocal on “Mad Lucas.”

I had to go out and get a tremolo pedal after making the record to replicate those sounds. As far as pedals go, I think I just had an orange Boss DS-1, a digital delay and maybe my Ibanez Tube King. The reverb on my JCM900 still worked back then, so I didn’t need a pedal for that.

Your Strat Ultra was stolen. What happened?

That was my very first electric guitar. It was a gift from my sister for Christmas, and I just about died when it was stolen. We played a show in 1991, in Olympia, Washington, and I sat my guitar down on the stand and I turned my body to walk off. And before anybody knew it, a kid, who was maybe 11 or 12 years old, jumped onstage, grabbed my guitar, and went out the back.

Some members of Nirvana and their crew were there and they asked for the serial number of the guitar and said, “We'll keep our eyes open.”

[Although many online sources say Deal’s Strat Ultra is a 1992 model, it appears to be of 1990 vintage, with serial number N988911. While N9 serial numbers designate a Fender guitar of 1999 manufacture, the company inadvertently affixed a number of those preprinted decals to some 1990 models, according to support.fender.com.]

About a year later, I got a phone call from one of the crew people. The guitar had surfaced in a store and the serial number had been on a list, so they were notified. I sent the store some money and they shipped my guitar back. The finish was stripped, and it was done with a hammer and a chisel, and then this weird green automotive paint was on some of it. But the serial number was perfect! I never got the guitar fixed because it had gone through a trauma. And I needed to respect that.

The Breeders’ Last Splash (30th Anniversary Edition) is available to buy and stream now