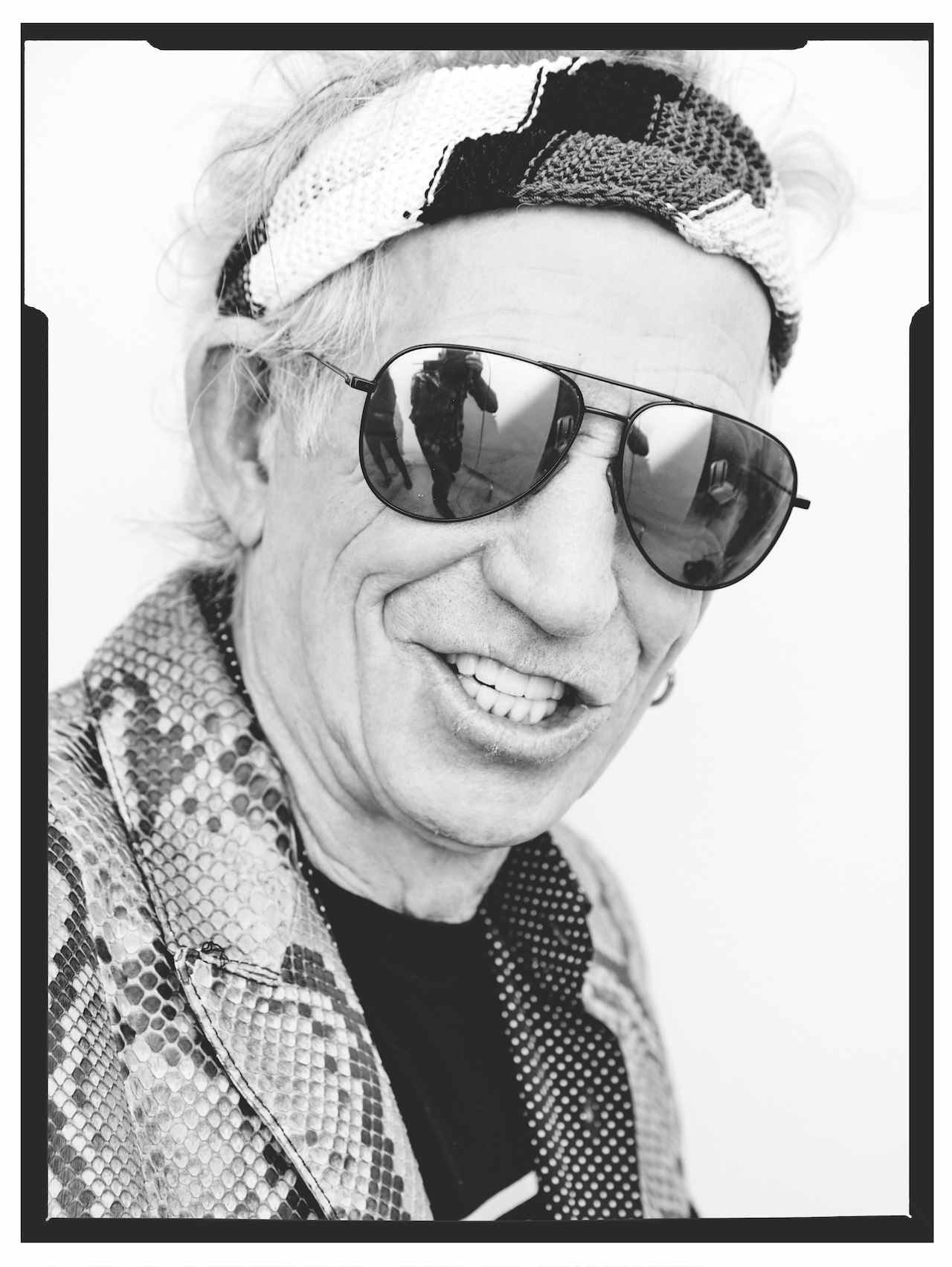

“It’s the sound of the Stones: a five-string with a six-string on top. Guitars are amazing things – you can make an orchestra out of them…” Keith Richards on life without Charlie, The Beatles and the Stones, and new album Hackney Diamonds

In an exclusive interview, Keith Richards talks about the magic of the new album Hackney Diamonds, and why losing a string created a whole new sound for the Rolling Stones

Keith Richards once humorously quipped, “Guitar is easy — all it takes is five fingers, six strings and one asshole.” Yes, easy perhaps, but few have wielded the instrument with as much imagination, grit and panache as the legendary Rolling Stone himself.

Over the past six decades, the guitarist has unleashed a torrent of timeless riffs, gracing hits like “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” “Satisfaction,” “Honky Tonk Women,” “Start Me Up,” “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’” and “Happy.”

And now, brace yourselves for a dozen more hot rocks. At the venerable age of 79, Richards, accompanied by his eternally youthful crew, the Rolling Stones, has put the final touches on their 26th U.S. studio album. Lord knows, it’s been a long time comin’. Nearly eight years have passed since the release of their 2016 blues covers album, Blue and Lonesome, and twice that time since their last batch of original songs, 2005’s A Bigger Bang.

The good news is the wait’s been worth it. Packed with killer tunes and those trademark Keef guitar hooks, Hackney Diamonds (Geffen) stands tall among their very best work. Bold, textured and unapologetically ambitious it recalls classics like Let It Bleed (1969) and Exile on Main St. (1972).

The album also features guest appearances by some of rock’s greatest luminaries, including Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder, Elton John, Lady Gaga and even original Stones bassist Bill Wyman, who hasn’t recorded with the band for almost 30 years.

Guest cameos often distract more than they add, but the Stones have artfully deployed these music icons in surprisingly subtle and complementary ways. Wonder and Lady Gaga, for example, add just the right touch of soulful elegance to the celestial gospel rave-up “Sweet Sounds of Heaven,” while Elton discreetly provides some tastefully rollicking piano on two tracks.

Perhaps the biggest surprise is McCartney’s contribution. Beatle Paul, known primarily for his timeless love songs and gift for melody, goes against type and unleashes the mother of all snarling fuzz-bass lines on “Bite My Head Off,” an exhilarating punk rocker that tears the roof off the joint.

“To be honest, if Paul had come another day, he’d probably have been on a different song,” Richards says with a laugh. “It wasn’t calculated. It just happened to be the flavor of the month that day.

The guitarist maintains that the album’s creation was “fun, quick and effortless,” yet he admits it wasn’t without a few tears. Hackney Diamonds marks the band’s first production since the passing of Charlie Watts, one of rock’s preeminent drummers, if not the unrivaled champion, who died on August 24, 2021, at the age of 80. The loss of the band’s inimitable “engine room” was a bitter pill to swallow.

“Charlie was such a part of me and what I played, I haven’t quite come to terms with it yet,” Richards says somberly.

Fortunately, the band was able to find a suitable replacement for Watts with percussionist Steve Jordan, who has played with Richards in the guitarist’s various side projects over the past couple decades. And as Keith explains in the following conversation, it was Watts himself who crowned Jordan as his heir apparent.

Despite the loss of their longtime drummer, the Rolling Stones — Richards, singer Mick Jagger and guitarist Ronnie Wood — are in top form on the album, with some credit going to their young 32-year-old producer, ironically named Andrew Watt.

While it may surprise some that the Stones would put their legacy in the hands of someone a fraction of their age, Watt has built a solid reputation by crafting excellent albums for several top-shelf veteran rockers and rappers, like Ozzy Osbourne, Eddie Vedder, Iggy Pop, Post Malone and Juice Wrld, all of which earned him the prestigious 2021 Grammy Award for Producer of the Year.

But earning a Grammy is one thing, and gaining the respect of Richards, who undoubtedly has seen it all (and then some) is a whole ’nother matter.

The guitarist, however, makes it abundantly clear that he enjoyed working with the producer and credits him with getting the album done in a month or two, something that he considers almost miraculous.

I was overwhelmed by how diverse and fresh the whole album sounds. I understand it had a lengthy evolution.

Yeah, it took a while to get it going, but when we finished touring last year, Mick and I decided, Let’s just blitz a record, man, because we were being too relaxed about it and not really putting it together. We sort of made a project of it and said, Let’s get a guy that can push this thing with us. Mick found Andy Watt, and I’ve got to say, it was quite an experience working with him.

He’s very young, very enthusiastic, and we worked very fast on it once it got going. Initially, I was almost a little skeptical that we would ever finish another album, because it’s been so long since we put new stuff out. For a minute, I was sorta waiting to see what would happen.

Sometimes it’s good to have a deadline.

Yeah, exactly. That was Mick’s opinion. I said, “If you’ve got enough material, let’s go for it.” That’s how it happened.

That’s the sound of a Stones record: a five-string with a six-string on top, and Ronnie. It always creates a beautiful blend. A great example is how it sounds with Ronnie’s Dobro on [the Hackney Diamonds track] “Dreamy Skies”

It’s been 15 years since your last batch of original songs with the Stones, and I was wondering, as an artist, did you feel like you had something to prove?

I’m not sure whether we needed to prove anything. I mean, maybe we needed to prove we could still make a record. But Mick had been building up material, and once I heard it, I said, “Well, we need to do a little bit of movement here or work on the bridge and stuff.”

But a lot of the time, his ideas were together, so once we got in the studio, it wasn’t that difficult. It was also incredible to work with Steve Jordan for the first time on a Stones record. It was like presenting a “Stones now” kind of thing. [laughs]

The first two songs, “Angry” and “Get Close,” begin with great kick-ass rhythm guitar hooks. Does your songwriting process usually begin with finding a great guitar riff?

Kind of, although from my point of view, there’s no fixed formula for writing a song. I feel more like I’m an antenna than a creator, particularly because, to me, songs seem to come from somewhere out there in the cosmos. If I sit down with a guitar or a piano and just start playing, eventually a song comes. It’s a bad day when it doesn’t. [laughs]

Most of the time I feel like I’m just receiving inspiration from everything that has gone on before me, and then put it through my own point of view, and then sort of pass it on. I almost don’t feel any sense of ownership.

Most guitar players are pretty good at noodling around. The hope is that you stumble onto something interesting.

Yeah, exactly. Right. I mean, sometimes an idea just finds you. Regardless, guitar playing is just a fantastic form of relaxation. Everybody should have one! [laughs]

I know this is very personal, but how did Charlie Watts’ death affect you?

All I can say is that I loved the man dearly, and I miss him. I still have conversations with the fucker. [laughs]

You worked with drummer Steve Jordan for quite a few years on your side projects with the X-Pensive Winos. That must’ve made the transition a bit easier.

When I started putting the Winos together, it was Charlie Watts who told me, “If you’re going to work with anybody else, Steve Jordan is your man.” So Steve’s been wearing that mantle for a while, and we all knew him, so in that way the transfer wasn’t that difficult. But, still, it’s impossible to put into words what Charlie meant to us. He was just a fantastic friend and so much more.

When I started putting the Winos together, it was Charlie Watts who told me, “If you’re going to work with anybody else, Steve Jordan is your man

I know that Charlie was a huge fan of drummers. He was a real scholar. For Steve to get his endorsement is significant.

Absolutely. And you’re right about Charlie, he was totally invested in the great drummers of the ’30s and ’40s, like Max Roach and Art Blakey. Swing drummers were his joy. He was a historian on them. Yeah. He knew just about everything about ’em. The history side of it was very important for Charlie.

What did he appreciate about Steve’s playing?

I think he recognized him as a soulmate. Steve had been listening to Charlie since he was a kid and knew his playing from the ground up. He can do an incredible imitation of Charlie’s drumming, and I think Charlie got a kick out of that.

It’s not easy to catch the nuances of Charlie’s feel.

No, it isn’t. No. He had his own little ways of playing and some of those secrets he’s taken with him.

Charlie appears on two tracks on Hackney Diamonds: “Mess It Up” and “Live by the Sword.” The album credits list that his performances were produced by Don Was, who produced your previous two albums, so I imagine the genesis of those songs came from earlier sessions.

We had just started working on those tracks a few years ago, before Covid shut everything down. We left Charlie’s tracks as they were and re-did the vocals and everything else with Andy Watt. As soon as you hear that snare, you know it’s him.

Did Charlie have much input on how your songs were constructed?

No, I wouldn’t say that. He would listen to whatever we brought in and made his own decisions about how to play it, but Charlie thought that a song was to be played, and I believe he didn’t think that songwriting was a part of his job. He just liked songs, and if he liked them, he’d play ’em.

You must have had an incredible connection with him, because I know a lot of guitar players play to the drummer.

Yeah, especially rock and roll players, if the drummer is the right kind of drummer. Charlie could swing and he could roll it a little more than most straight rock drummers. Charlie always added a jazz tinge to everything he played, so there was always that slightly different feel about the Stones’ music.

There are a lot of what I call “full-circle moments” on the record, moments that take you back to the band’s origins. One is having Bill Wyman play in the studio with the band after a 30-year absence. How did that come about?

Well, Bill and I have regularly stayed in touch through the years. He quite often sends me bits of information over the phone. I always see him when I go to England. In fact, I’m going to London next week, and I have no doubt that I’ll see him then. I’m not sure if he sees a lot of Mick and Ronnie, but I always make a sure point of getting to him.We just thought it would be cool to have him on one of the last tracks with Charlie. A reunion of sorts.

Unfortunately, we weren’t in the same room together to record that, because we all just overdubbed to Charlie’s original track. But we’re all still good friends. The Stones are still the Stones in their own way. I mean, no band has lasted this long, so there is really nothing to compare it with. We see each other when we can. It’s not like we forgot each other just because somebody leaves the band.

Paul McCartney had been doing some work with Andrew Watt as well, and happened to be around and dropped by. I don’t even think he intended to play bass on a track, but once we he was there, I just said, “Come on, you’re in. You ain’t leaving until you play!"

How did Paul McCartney enter the picture? I think it shocked everyone when it was announced that he was going to be on a Rolling Stones track.

He had been doing some work with Andrew Watt as well, and happened to be around and dropped by. I don’t even think he intended to play bass on a track, but once we he was there, I just said, “Come on, you’re in. You ain’t leaving until you play!” [laughs]

Famously, John [Lennon] and Paul wrote “I Wanna Be Your Man” for the Stones, and it became your first hit in England.

The Beatles and the Stones have been basically joined together at the hips from the beginning. We were totally different bands, but we knew each other well. I think we first met them in the fall of ’62, when they came down to see us play in London, and from there, every now and again, we’d get in touch.

Later, John and Paul sang on “We Love You” and on “Dandelion.” We’ve always sort of been in touch. Ronnie and I used to hang with George Harrison quite a bit in the 1970s, so there’s always been an open door between the Beatles and the Stones. We were the only ones that knew what it’s like to have that extreme kind of fame in the 1960s, so that created a bond.

Another “full circle moment” comes at the end of the record, when you and Mick perform a terrific, intimate duet of Muddy Waters’ “Rolling Stones Blues,” the song that gave your band its name.

That was Andrew’s idea. He turned up at the studio with a 1920s Gibson L-4 acoustic and asked us to do that Muddy thing. Ironically, I’d never played that song before, but the guitar was beautiful, and we did it in a couple of takes. The guitar that he laid on me was just the perfect sort of instrument for the job. It was perfectly archaic and, I must confess, pretty difficult to play. [laughs]

What does the music of Muddy Waters mean to you?

It’s the foundation. The blues was what I was chasing as a young man, and at one point I was going to stay there, and it was only rock and roll that got me out. [laughs] But to me, if you’re a rock musician, it’s essential to have a grounding in the blues, and it doesn’t get much better than Muddy Waters.

When I heard that song at the end of the album, I thought it would be a perfect way to end your recording legacy. You know, “Here’s where it started, and this is the way it’s ending.” Were you concerned that people might interpret it that way?

Man, I’ve never even come close to thinking of wrapping up the Rolling Stones’ story, so my answer to that is “Absolutely not.” It was just a cool way of wrapping up this album, and the story so far. We plan to keep working. I know we’re going to work next year. Making music is still quite exciting for me.

I hadn’t realized how long it was since our last album, I think eight years ago or something. It’s funny how time flies, man, but I’m enjoying the process of releasing a new record and seeing what happens.

Since the 1970s, the Stones have been a fluid entity. You had all these adjunct members, like pianist Nicky Hopkins, guitarist Mick Taylor or saxophonist Bobby Keys, that came and went. Do you feel like that was an essential element in keeping the band interesting and evolving?

There’s some truth to that, but it wasn’t intentional. It was just, “Hey, we need a piano, we need a sax.” And the best guys just kept hanging around. [laughs] But you’re absolutely right: All of that extra talent and new blood has always helped the Rolling Stones. Ian Stewart was our first piano player, and in many ways the Rolling Stones were his band. But I mean, God, man, it’s been 60 years. You’re going to go through a few changes, right? [laughs]

It’s super smart to bounce ideas off new musicians, but most bands seem to believe that it “dilutes the brand.”

Yeah, I don’t understand that way of thinking. We had Stevie Wonder and Lady Gaga bounce in too, which was a surprise, and it came out cool.

I was a little nervous when I heard Lady Gaga was going to be on a track. I didn’t know where that was going to go, but I have to say, “Sweet Sounds of Heaven” is one of my favorite songs on the record.

Right, I don’t blame you. I understand what you were thinking, but she’s one of the Stones now.

Her gospel singing on the song is pretty righteous.

She’s a talented piece of work. It also helped to have Stevie Wonder playing keyboards. Having the both of them in the same room was pretty interesting.

“Sweet Sounds of Heaven” is built around a textbook gospel chord progression. Did that come from you?

The sound and feel of gospel runs through almost everything we’ve ever done, but Mick and I never actually pinned it down in such a specific way. “Sweet Sounds of Heaven” started as more an Otis Redding–style soul music thing and evolved from there. Soul music and gospel are just a part of us, and at the right time it suddenly comes out.

There was no sort of premeditated decision to do a gospel thing. Mick just had these lyrics, and then there it was. We worked it out while we were all in a room together, so it felt very organic. I don’t think that song could’ve come together any other way. I was wondering about the false ending at the time. I didn’t get it. But then I got into the flow of it, and I think it really works.

I’m a huge Stevie Wonder fan, and we haven’t heard much from him in recent years. He sounds great on the track and seems like he has so much to offer.

We used to work with Stevie on the road quite a lot in the 1970s, so we’ve known each other for quite a while. But Stevie does what he wants to do, and when he wants to do it, he does it.

As you’ve noted, the album is produced by Andrew Watt. He’s much younger than you guys. I think he was only 15 years old when you came out with your last batch of originals. What did he bring to the table?

He brought exactly what we wanted: energy and a fresh mind. He knew our stuff back to front, and I think he had a ball making the Stones’ record. It was fun to make, very quick, compared to a lot of our records. We did most of it in a month or two. I enjoyed working with him.

Well, you’ve got kids, so I imagine that you can respect the value of a younger perspective, too.

Right. It rubs off.

All of that extra talent and new blood has always helped the Rolling Stones. Ian Stewart was our first piano player, and in many ways the Rolling Stones were his band. But I mean, God, man, it’s been 60 years. You’re going to go through a few changes, right?

If your ears are open, sometimes you can learn some new things.

Right. And it’s all about listening. It’s music. There’s something there.

One of the more striking elements on the record are Mick’s vocals. His approach is more direct and less stylized than in recent years. It’s almost a return to way he sang in the 1960s with producer Andrew Loog Oldham.

Oh, that’s interesting. Maybe it’s because both producers are named Andrew! [laughs] But you make a point. Mick worked hard, and I think he put more consideration into each song rather than just doing it. It was my observation that he thought a lot more about the vocals than usual.

They felt more honest.

Yeah, I get your picture. I had pretty much the same impression as you on that, but I really put it down to the fact that Andrew and Mick worked very tightly on each track.

On “Tell Me Straight,” your lead vocal also has a new vitality. You’re really belting it out.

People have been telling me I sound stronger after I stopped smoking cigarettes in 2019. When we went out on the road a couple years ago, the sound guys started making comments. They were like, “Man, your voice… what’s happening?” Since then, singing has felt different, and I’m enjoying it more.

You sound like a kid on that song!

There’s probably an age when you start to go into reverse. And I’m probably in it. [laughs]

“Tell Me Straight” feels like a life philosophy, sort of a song you were born to write: part mythic, part hardcore truth.

Oh, cool. It came kind of like that. Once it was on the roller, these chords appeared and then the rest of it seemed to fall into place around it. I knew it was getting pretty good because Mick tried to steal it! I had to say, “Uh-uh buddy. I’m doin’ this one.” [laughs]

There are a lot of guitars on the album. Lots of texture.

My five-string Tele is on a good half of the tracks, but there’s also a lot of the Gibson. That’s not unusual. I’ve never just used one guitar in the studio, but I’ve been getting know this ’59 Gibson ES-355 lately, and I really enjoy playing it.

In the early days of the Stones, you leaned pretty hard into Gibson Les Pauls, and then there was a bit of a shift. Do you remember what drew you into using a Fender Telecaster?

I don’t know how I started moving in that direction. I think it was something to do with the way I was playing, and a Telecaster made it easier. But I’ve always loved Gibson guitars, and, I mean, there’s a lot of overdubs on everything here, so as usual, with every Rolling Stones record, there’s a great mixture of different guitars.

Fender and Gibson guitars make a great time-honored pairing.

And then of course, it depends what amp you’re going to use. Yeah, it’s a big difference. I used Fender Twins most of the time, with the occasional Fender Champ when I was looking for something different.

I’d like to ask you a few questions about the appeal of playing your five-string Tele tuned to open G [G, D, G, B, D]. Is it because it automatically creates a great blend with a standard six-string?

Yeah, that’s part of it. That’s the sound of a Stones record: a five-string with a six-string on top, and Ronnie. It always creates a beautiful blend. A great example is how it sounds with Ronnie’s Dobro on [the Hackney Diamonds track] “Dreamy Skies.” You always have to play around with the amps a bit, but guitars are amazing things. You can make an orchestra out of them with just a simple blend.

Your band arrangements tend to be a little dense. In addition to a few guitars, there are often some keyboards, horns and backing vocals. Do you find that by eliminating your low sixth string, it opens the mix up so other instruments can be properly heard?

Yes! It’s always been the mystery to me why so much space opens up for other instruments by taking off the bottom string. You’re right, but I can’t really put my finger on a reason why, but somehow that one extra note disappearing allows for all kinds of other instruments to come through. It’s just one of those things, I guess.

What was it like working with Ronnie on this record? Do you guys spend a lot of time figuring out those guitar blends?

Truth is, it’s almost never complicated. We just fit together. I mean, it’s like knit one, purl two, and it’s not something we need to think or talk about too much. If we thought about it, it would probably become too studied. It either works or it doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, then we try it another way. But usually, Ronnie and I just fall into a groove without even discussing it.

Would you mind just talking about a couple of older songs? When people ask me about the importance of rhythm guitar, I always direct them to “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” from your Sticky Fingers album. Everyone focuses on the extended solos by Bobby Keys and Mick Taylor, but what kills me are all the different rhythm parts that you use to frame those solos.

If I can remember rightly, I was really focused on working on the tuning thing and different ways of playing the guitar. I think it was at the time when I was really just balancing between playing with open tunings and regular tunings, so all kinds of different things were sort of coming out.

That was with [producer] Jimmy Miller, who loved to play around with stuff like that. The track really grew while we were playing it. It was a good day.

Okay, here’s another one: “Love in Vain” [from 1969’s Let It Bleed], your re-invention of the classic Robert Johnson blues song. No one can play like Robert — and you were probably smart to not even try — but your arrangement is equally terrific.

I’ve always loved that tune, and I always thought there was something about the melody that suggested it wasn’t just a blues song. I heard a bit of country or folk in it, so I attacked it from that perspective. I remember thinking I wasn’t going to try to play it like Robert, and I wasn’t even going to play it like a blues. I’m going to pick out the notes and take it in a different direction.

It just so happened that both Mick Jagger and Mick Taylor cottoned on to the idea, and we found ourselves doing it a new way.

One last thing. Another great musician passed this year. What did you think of Jeff Beck? And is there any truth that he was being considered for the Stones after Mick Taylor left?

Jeff? No, we felt that Jeff had his own furrow to plow and that he was not a team man. He was a soloist to the max. He was such an individualist. It wouldn’t have worked with the Stones at all. We’re all about teamwork. But don’t get me wrong, he was a tremendous player. The odd times we got together, I was always amazed by the stuff that he did with his tremolo bar.

He was one of the best, man, and he’s going to be missed.

So, do you think your next album will be done…

…sometime before the next century? Yeah, I do hope so. [laughs] And I suppose given the normal pattern of things, we’ll probably be on the road next year. And after that, we’ll see.

Hackney Diamonds by the Rolling Stones is out now and available to buy or stream

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Brad Tolinski was the Editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. He is the author of Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song