"I feel like George Lucas, where you helped create this thing that becomes not just movies and stuff but a culture. We created a culture with Kiss…" The Gene Simmons interview

"At the end of the day, Mother Nature and Father Time get their comeuppance,” Gene Simmons offers, philosophically. “They put their hand out and say, ‘Okay, time for you to pay us for this wonderful life you’ve led.’ You have to have the dignity, self-respect and pride to know when it’s time to get off that stage.”

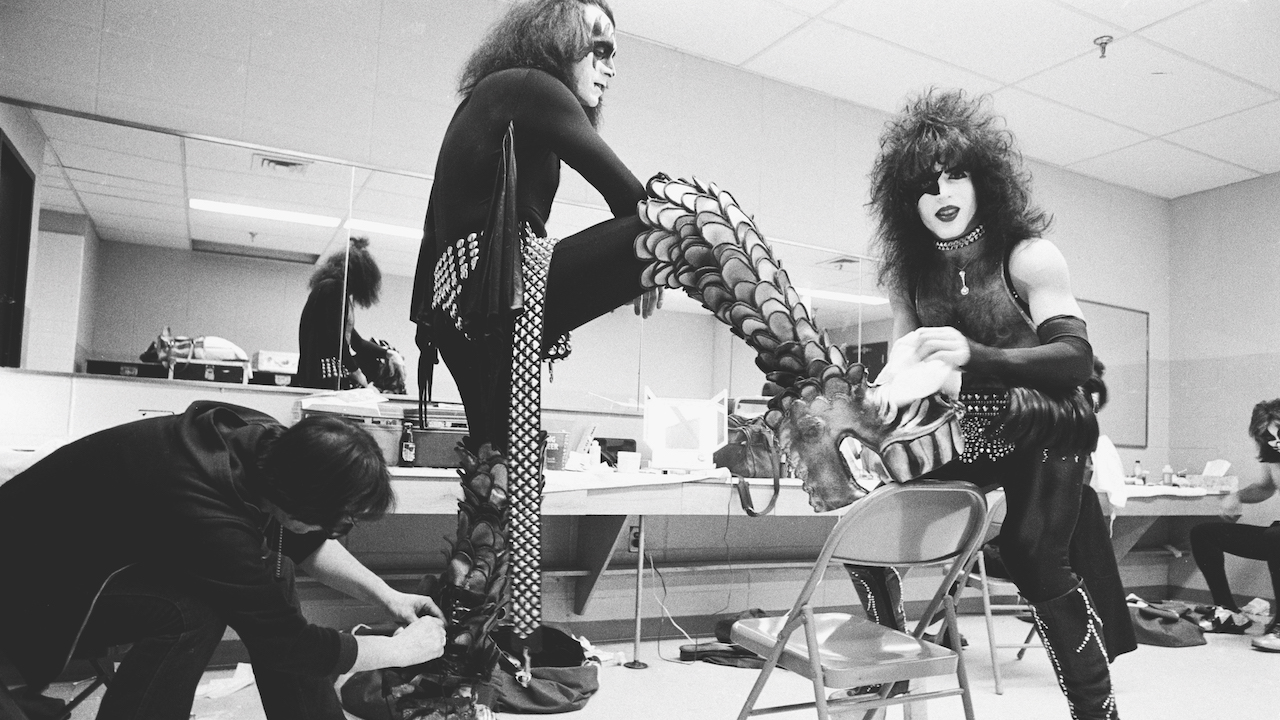

Making that move hasn’t been easy for Simmons. When Kiss wrapped up their nearly four-year-long End of the Road tour last week, it brought the group’s 50-year reign to a rousing finale. Kiss may have taken their sweet time crossing the finish line, but when it’s over, the 74-year-old bassist will be able to look back at a life and career of his own choosing and making.

It’s not an exaggeration to say no dream was impossible to achieve for Simmons. He was born into a “dirt-poor” family and immigrated to the United States from Israel when he was just eight.

He learned to speak English from watching TV and, later, in 1964, was inspired to become a rock musician after seeing the Beatles perform on The Ed Sullivan Show. Fueled by a tsunami of ambition, ego and a relentless work ethic, his larger-than-life vision brought him and his bandmates unfathomable fame and fortune and entry into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

As Kiss play the final dates on their End of the Road tour, which winds up, aptly, in their hometown with a two-gig engagement at Madison Square Garden, we caught up with the Demon for a look back at how it all began — and what happens when the curtain rings down on Kiss for the final time.

Let’s go back almost 50 years to the first Kiss gig at Coventry, formerly the Popcorn Pub, in Queens, New York.

I remember passing by a place that used to be the Popcorn Pub in Woodside, Queens, New York. It was not a very cool place. Paul and I were just coming off of Wicked Lester [their pre-Kiss band]. We had a manager whose name was Lew Linet. He managed [singer-songwriter] Diana Marcovitz and a band called J.F. Murphy & Free Flowing Salt, who were signed to Elektra, I believe. Eddie Kramer may have engineered their record, or produced it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Lew was a nice guy, but he was not a rock guy. As Paul and I were transitioning from Wicked Lester to Kiss, Peter [Criss] joined us in the fall of 1972 and we played as a trio for two months before Ace [Frehley] came in.

I paid for the loft we were rehearsing in, because I had a job and I was able to afford to pay most of the $200-a-month rent. Paul would chip in every once in a while when he drove a cab. Paul and I went down to Manny’s Music Shop on 48th Street to buy a Peavey sound system, and I remember he did contribute some money, but whatever shortfall there was, I’d have to cover.

What kind of bass were you playing for those shows?

We hadn’t as yet done shows. We were rehearsing. There was a guy named Charlie LoBue who made handmade guitars. I remember telling him to build me a smaller-body bass guitar, almost the size of a Les Paul Junior, with that kind of body style and with two horns. That would later become the prototype for what became my Punisher, a bass with a fully exposed neck so I could slide all the way up the neck and play harmonies with the guitar, so it wouldn’t sound like a bass playing it.

So we were a trio at this point, and for a short time we thought, Hey, we’re going to be a power trio. Paul could sing, I could sing, and Peter could sing. We liked his “whiskey” voice. Paul could write songs, and I could write songs, so what else do you need? And maybe we’d write songs more like the Who, where you didn’t have to have lots of solo guitar playing. We were not yet called Kiss. As a power trio, we were playing new songs we’d just written, like “Deuce,” “Strutter” and “Black Diamond.”

Originally, we thought, Gee, this doesn’t sound bad; you don’t need a lead guitar. But then when the middle section of “Deuce” came up, we couldn’t just keep playing the chords over and over again. Paul didn’t feel comfortable enough to do the solos, so we started to look for a lead guitar player. But before that, Lew Linet came in and had ear plugs on, and he kept saying, “Why are you guys playing so loudly?” So we immediately knew, this is not the guy for us; he doesn’t understand.

And in the nicest way, we went up to his office and said we should split, and that it’s just not working for us, and he agreed and was a gentleman about it, and so were we. And we wished him well. And then, of course, when Ace joined the band, those stories we’ve told about that day are like a fictional cartoon show.

It might have been a segment of The Simpsons, where this guy comes in with an orange sneaker and a red sneaker and, oblivious to anybody else auditioning any other guitar player, he just plugs in and starts playing.

And you screamed at him and told him to shut up.

Exactly right. Poor Bob Kulick was just finishing up auditioning, and we knew it wasn’t working. Bob could play, but it was left up to me to give someone the bad news. I walked up to Ace with poor Bob Kulick in the room, looking around and not knowing what’s going on.

I said to Ace, “Can you shut the fuck up? What are you doing? Sit down. We’re in the middle of auditioning.” Ace said, “Oh, I’m sorry.” He was oblivious to the fact that there was anybody there. But even with his eccentricities, Ace was our guy.

Ace joined in December 1972, and less than two months later Kiss played their first gig at Coventry, on January 30, 1973. Why did you choose this club?

I called the Daisy in Amityville, New York to get us gigs, and I was also the guy that called Coventry. For one thing, we couldn’t play anywhere else. There was no demand. We were a brand-new band, and we weren’t playing hits. You could get a gig more easily at a club if you played the local hits.

We were not playing covers. We were a totally original band. Not only that, right around that time, we decided, Hey, let’s wear makeup. So that was happening at the same time, but we didn’t have a manager.

For our first gig at Coventry, which we played a few times, we got the sum total of $35 for two or three nights. The fact that we got those Daisy and Coventry gigs is because I’m a silver-tongued devil. I tell people what they want to hear: “Oh, we’re the best thing since sliced bread,” and, “We’re heavy metal masters” — we used that term when it wasn’t commonly used, and we didn’t have a clue what it meant.

For that first show at Coventry, there were about 10 people there: my then-girlfriend Jan Walsh; her best friend, who was going out with her brother; Lydia, Peter Criss’s wife at the time; and very few others. Nobody knew and nobody cared. But when we were onstage doing “Strutter,” “Deuce” and “Black Diamond,” we felt it.

We knew it. It was finally the chemistry, finally the sound and the vibe and the look, with the right guys that we had imagined, and very few things in life turn out that way. It’s that chemistry thing. Now, of course, some chemistry can be volatile. You put the wrong chemistry together and it burns up or explodes.

When do you think you, Paul, Ace and Peter really started to find your mojo as live performers?

Well, initially, there was that sense of, Wow, this is a real band, and that happened at the Daisy. People had come to see us. This was after Coventry. When we were onstage, there was a real energy. You’d look across the stage and we’re doing all this original material, and some of it, like “Too Young” and “Life in the Woods,” we only played back in the club days. “Too Young” was written by me and was cut down and turned into the song “Acrobat.”

But there was a full three or four minutes after that, and we’re listening to ourselves and playing, looking across the stage and really getting off on it. In fact, Ace, had the makeup on without the white face, and when he looked into the Mylar reflection of Peter’s drum kit, he started laughing. He was getting off on his own thing.

Later on in our set, we’re hearing the guitar playing and it sounds really good, and Ace is rocking out. And then we look across the stage — and he’s not onstage! Somehow he’d climbed onto this ledge off the stage and was rocking out. He’s always been like that.

And of course, during the performance of “Life in the Woods” — a “clap your hands together” kind of song — I remember stepping off the stage, in makeup, and going up to a girl who was clearly pregnant and taking the drink out of her hands, grabbing her hands and forcing her to clap. There was also a conga line that formed during that song. All kinds of crazy stuff was happening. We were finding our way at that early stage.

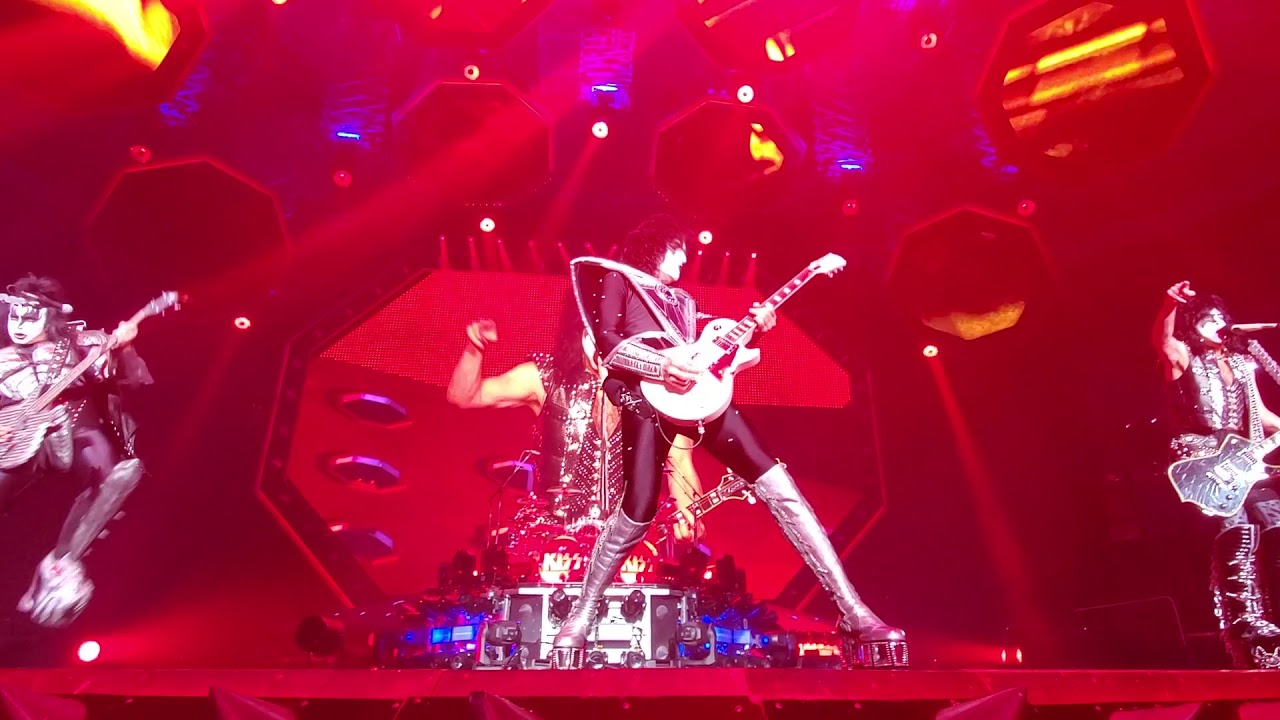

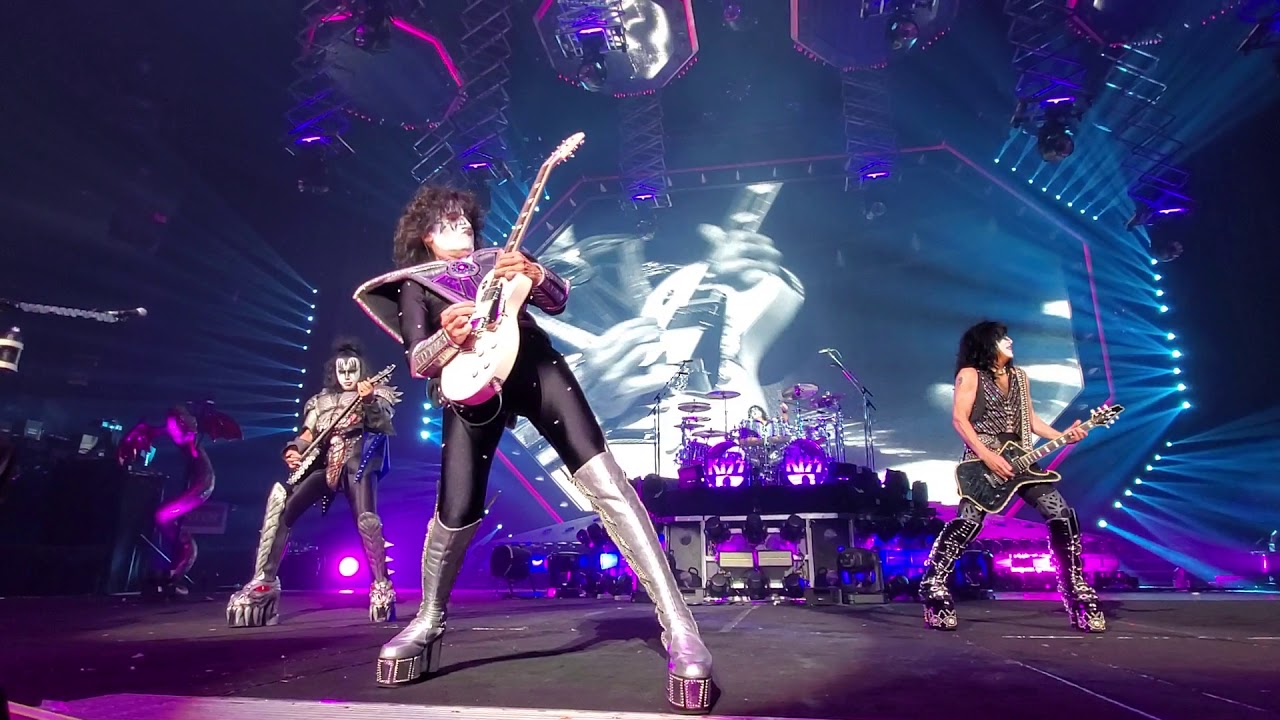

As Kiss ramps up for the last dates on “The End of the Road” tour and the final shows the band will ever perform, take us through the evolution of a Kiss show — from the formative days playing in local dives into the ’70s OG band’s heyday and to the present day with the End of the Road tour and its over-the-top theatrics and bombast.

Managers either have vision and see the future — the big picture — or they’re like a bookkeeper, just keeping tabs on things. We were lucky to meet a guy named Bill Aucoin, who had a music TV show called Flipside, where they interviewed John Lennon in a recording studio. He was one of the names I found in the Billboard year-end issue, where they list all the major movers and shakers in the music business.

I was working in an office at that point, the Puerto Rican Interagency Council, and I put together the bio kit. Peter, Paul and Ace were putting up posters around town. I remember mailing out invites to everybody, every record president.

Bill Aucoin, even though he was not a manager or a producer or with a record label, he got the photo and the invite, and he showed up at our show at the Hotel Diplomat. For our show, we were still doing what we did at Coventry and the Daisy. Bill saw us and said, “Okay, I’m going to get you a deal in two weeks or you don’t have to use me as a manager.”

And he did. From there, he became the captain of the ship. He started talking early on about trademarks, and we didn’t know what that was. “Yeah, we’re going to trademark your faces so nobody can copy you.”

“Oh, that sounds like a good idea.”

Then he said, “We don’t want to let people see your real faces.” We said, “Well, why not? What about chicks and all that?” “No, no, you’ve got to keep up the mystery.” “Oh, okay, that sounds like a good idea.” He came up with that.

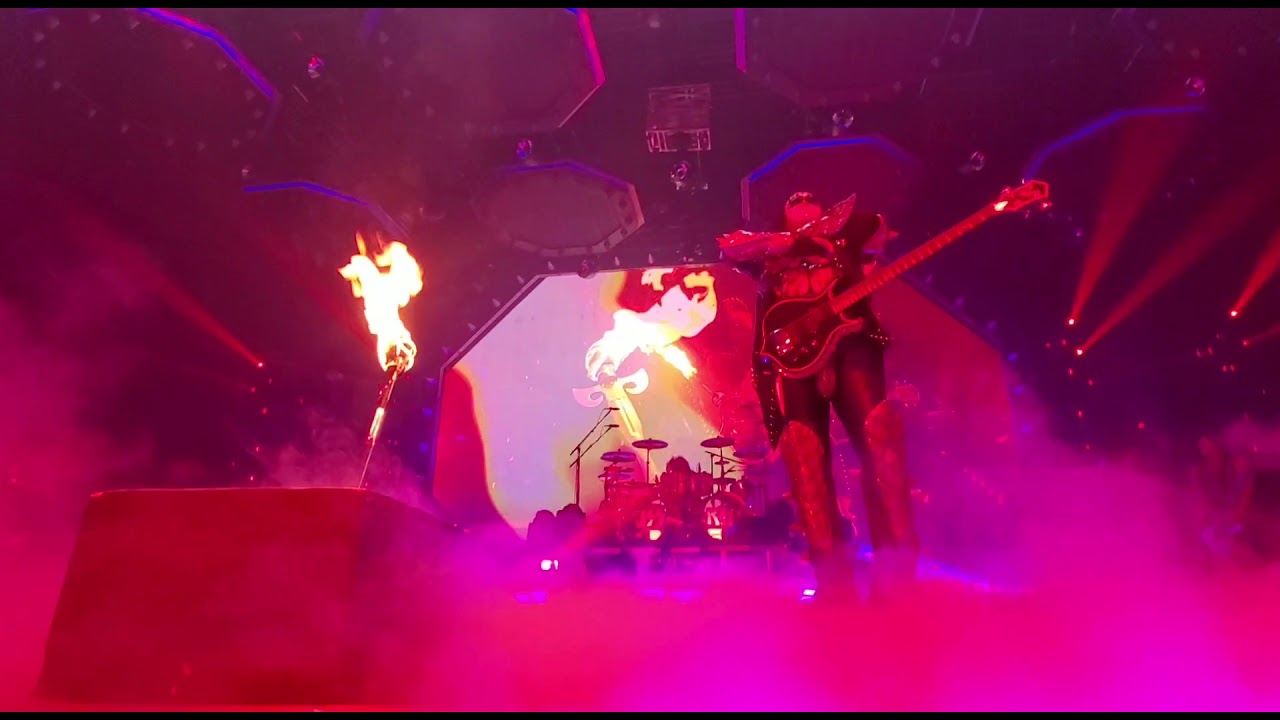

And it was Bill Aucoin who said, “Okay, we need to find gags.” Bill scoured around and found a company that could levitate the drum set. Bill brought in a magician named Amazo or something, a fire-breathing guy who was completely bald. We asked him, “Why are you bald?” and he said, “I have hair, but I shaved my head.” “Well, why do you want to do that?” And then when he spit fire in Bill Aucoin’s office and singed the ceiling, we said, “Oh, that’s why you shaved your head!” [laughs]

And for some reason Bill said, “One of you guys has got to spit fire during ‘Firehouse.’” We said, “What? We’re a rock band.” And he said, “Yeah, don’t worry about that.” And somehow I wound up being the guy to spit fire. And the lit candelabra we used onstage was also the idea of Bill Aucoin.

Whose idea was it to introduce the lighted Kiss sign?

That came from Bill Aucoin. Sean Delaney, who was Bill’s romantic partner and wrote songs with Paul, Ace and I, became our first tour manager. What happened in those early days is bands would just show up and play; you wouldn’t have any logos or anything. But we had this very heavy sign with our name that had to be connected to electricity. And when the Kiss logo turned on, it was blinding, so much so that when the blackouts happened, you still saw the Kiss logo etched into your retina.

We’d be opening for bands like Manfred Mann, Argent and Savoy Brown, and after we came off the stage, our logo would still be above their heads. As the English would say, we went down a storm and did very well, and we were called back to do encores.

The Destroyer tour ushered in a new level of theatrical presentation, which continues to evolve over the decades with the End of the Road stage set.

Yes, that’s right. Later on, Paul and sometimes I would sit down and draw ideas for a new stage show. But in the beginning, Sean Delaney and Bill Aucoin would bring in technical people and designers who would sit there and go, “Okay, how about this and how about that?” The stage show for the Destroyer, Rock & Roll Over and Love Gun tours, all those were clearly not our ideas.

In fact, we were rehearsing in a big airplane hangar in upstate New York, and when we came in and set up, in front of our eyes was something like a Disneyland haunted house, which was used on the Destroyer and Rock & Roll Over tours. We had no input in that.

How about the risers and the lighted stairs?

It was either Paul or myself that said, “Hey, how about lighting coming on, like Las Vegas? When the girls come down the stairs, the stairs light up.” That idea might have come from us, but I never want to take away from the fact that we had a real manager.

Bill Aucoin was a very important part of the creative vision, and so was Sean Delaney. I’m not sure who came up with the idea for the risers, but we continue to use that idea even today.

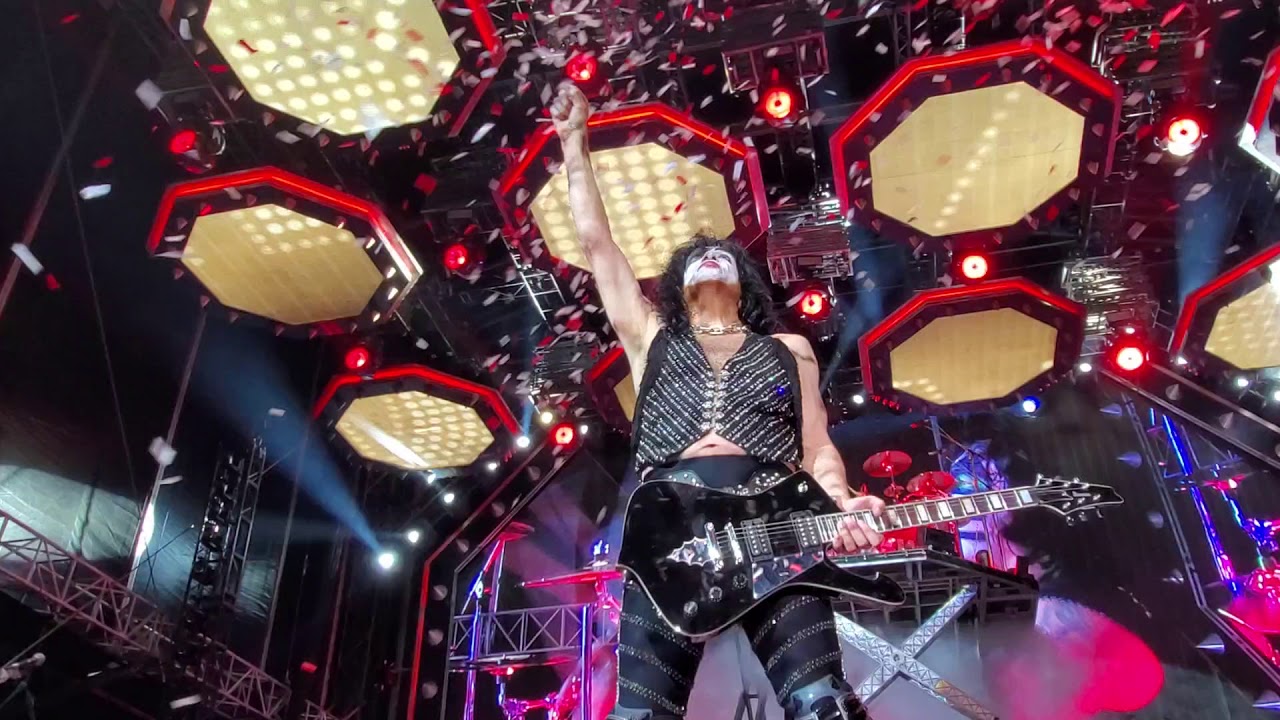

December 2nd at Madison Square Garden is the last Kiss show ever. During the last song, which will surely be “Rock and Roll All Nite,” what emotions will be running through you? Do you feel you’ll have a hard time keeping it together?

Yes. I can glibly sit here and talk about how I’ll be feeling for our last show, but I’m sure it’s going to be a different kind of a thing, and much deeper. I mean, what a journey it’s been! What a trip!

What are you going to miss the most when it’s over? I feel that Paul will be able to deal with it a little better. I think it’s going to be harder for you.

I feel like George Lucas, where you helped create this thing that becomes not just movies and stuff but a culture. Like, when you go to Comic Con or Star Wars conventions, people dress up and it’s how you look, how you walk, how you talk.

We created a culture with Kiss. And after Lucas sold to Disney, that doesn’t mean it goes away. You can see the vestiges, the conventions and the TV shows that continue on, and we intend on keeping Kiss going, but simply not as a touring band, and that comes out of pride.

So you’re thinking the December 2nd Madison Square Garden concert will be Kiss’s last show ever?

Yes, it will be the last Kiss show of all time. We’re not going to put on the makeup and put on shows anywhere. We have too much respect for what we’ve been able to accomplish, and every member that’s been in the band deserves a slice of the accolades. That includes [former guitarists] Mark St. John and even Vinnie Vincent, no matter how much trouble he caused us, or anguish.

Everybody contributed to this thing and they have a right to be proud, because it takes goddamn hard work. If you think it’s just about putting makeup on your face and you can have a 50-year career, boy, are you dreaming.

Kiss’ latest album: Kiss off the Soundboard: Live in Poughkeepsie is available to buy and stream now