Brian May Reflects on 50 Years of Queen's Regal, Operatic, and Peerless Rock Sound

In this Guitar Player exclusive, the rock icon looks back on Queen’s 50-year (and counting) reign and declares, “We’ll just press on with it.”

Brian May doesn’t recall particulars about every Queen show. But there is one – almost 50 years ago at London’s Imperial College, where the guitarist had previously studied physics as an undergrad – that sticks with him.

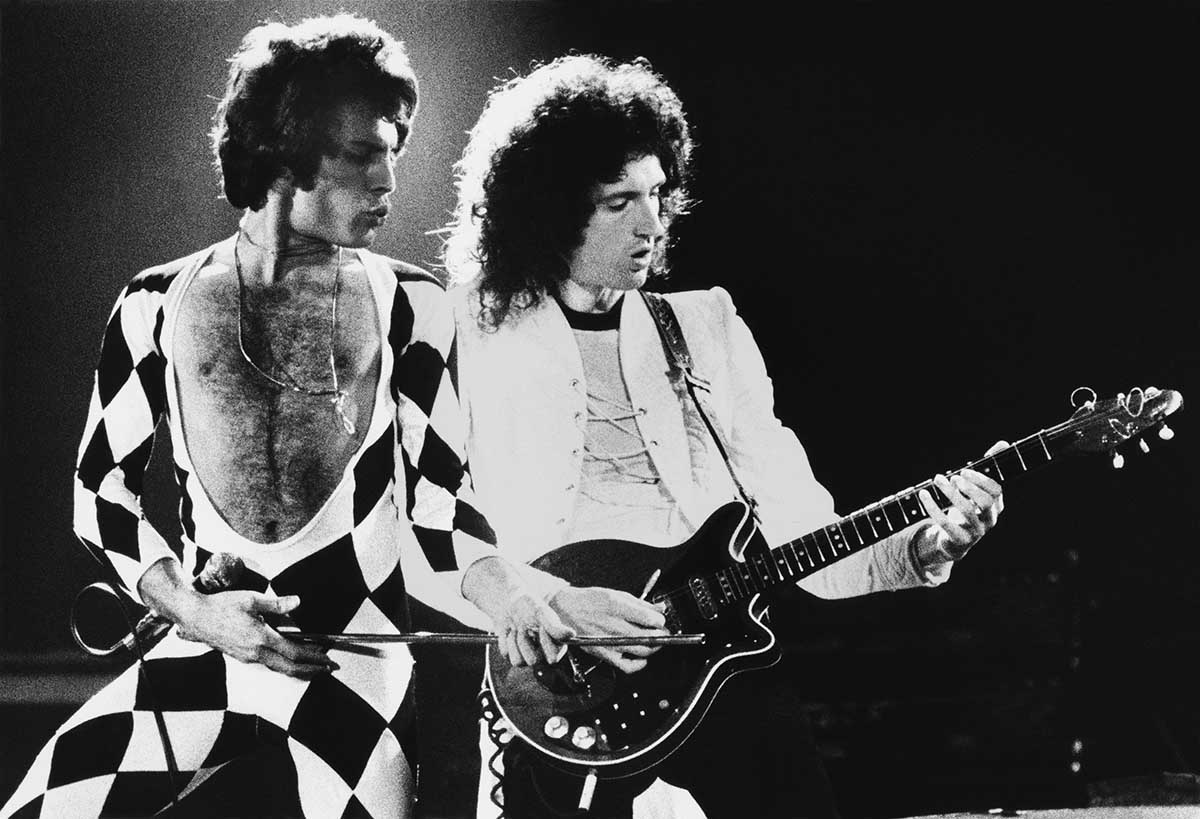

Why? For one, it was Queen’s first gig to be reviewed in a newspaper – and if you’re wondering, yes, it was a positive write-up. For another, because, in the 73-year-old guitarist’s words, “We had our full complement – we knew we finally had the right people in the band.”

These people, of course, were drummer Roger Taylor, with whom May had previously played in the late-’60s rock-pop-blues-progressive outfit Smile, Zanzibar-born singer Farrokh Bulsara, who by that time was answering to the name Freddie Mercury, and fresh-faced bassist John Deacon.

“So that was a big deal, for starters,” May says. But beyond the good reviews and winning combination of players onstage, May also recalls that performance being a standout thanks to the audience’s reaction.

“We had our first album coming out, and it felt like, for the first time, people knew what to expect from us,” he says. “The effect was phenomenal, because instead of going onstage and trying to persuade people that they might like what we do, we went onstage to a crowd of people who knew our music and wanted it. And they were giving us the energy to propel us to make those sounds that they’d cottoned on to.

“The feeling was incredible – it was like having your finger in a dam and a little trickle of water is coming out, and then suddenly the whole thing breaks down and you have this great, wonderful flood of energy.”

Today, Queen may not look quite the same – Mercury passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1991, and Deacon retired from music toward the end of that decade. But that flood of energy persists, with May and Taylor continuing to rock arenas the world over with current singer Adam Lambert.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Lest there be any doubt, 50 years after Deacon joined the band, in March 1971 – thus cementing the “full complement,” as it were – Queen remain as resonant, beloved, and popular as ever. The 2018 film Bohemian Rhapsody smashed box office records to become the all-time highest-grossing music biopic, with worldwide receipts of nearly $1 billion and a quartet of Academy Awards to its name.

Our songs were never elitist. At their core, they were songs about the joys and the sorrows and the pain that every man, woman, and child feels

As for the music? Using just one metric, Spotify, as an example, “Bohemian Rhapsody” has racked up close to a billion and a half streams on its way to becoming the most-listened-to classic-rock song on the service, but Queen’s next four top-streamed tracks – “Don’t Stop Me Now,” “Another One Bites the Dust,” “Under Pressure,” and “We Will Rock You” – all handily dwarf the numbers of anything by the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, and many of their other rock-legend peers.

It’s a “phenomenon,” as May puts it, and one that seemingly has no end. As for how he explains it? Despite Queen’s much venerated flair for grand and wildly dramatic musical gestures, “our songs were never elitist,” May says.

“At their core, they were songs about the joys and the sorrows and the pain that every man, woman, and child feels. They express the extreme emotions of non-extreme people – people that think they’re ordinary. And I think that’s why they have aligned with listeners.”

In honor of Queen’s 50th anniversary, May sat down with Guitar Player to look back on some of these songs, as well as recall key moments (the recording of their 1973 self-titled debut; their eye-opening 1974 tour with Mott the Hoople) and the various components – including his legendary Red Special guitar, homemade amps, and modded pedals – that have been crucial to the band’s development. But even with so much history behind him, May is still firmly focused on the present.

Late 2020 saw the release of the Queen + Adam Lambert concert document Live Around the World, which compiled performances from the group’s past six years on tour, and the plan going forward – pandemic permitting, of course – is to continue that around-the-globe jaunt once the world is safe for arena-sized pomp-rock spectacles again.

So May is quick to say that while the golden anniversary is a nice milestone, it presents at least two of the band’s members with a dilemma. “Roger and I asked, ‘Do we really want to be celebrating the fact that we’ve been here for 50 years?’” May says, and laughs.

“Instead, we decided, ‘Why don’t we just celebrate the fact that we’re here, that we’re still alive and, potentially, still performing.’” The show, as a great British rock band once sang, must go on. “The past is there, but why get all nostalgic?” May reasons. “We’ll just press on with it.”’

The characteristic Queen sound is a complex thing. But it’s all there – if perhaps in somewhat embryonic form – right at the beginning, on your 1973 self-titled debut. From the harmonized guitars to the stacked vocals to the epic compositions, you were already enacting some fairly advanced ideas, both musically and technologically.

You’re right, yeah. It was all bottled up in our heads and unable to get out. And even with the first album, it was a hard job getting it out because we were doing that record in little bits and pieces of time.

The people at the studio [Trident Studios in London] gave us the crumbs from the table. We would work during the cancellations or at three o’clock in the morning: “Come on boys, do a couple of hours!” So although we had the run of a good studio, we didn’t really have the opportunity to flex our muscles until the second album, when we actually had studio time booked.

But yeah, it was all there. We dreamed of these big vocal harmonies and guitar harmonies and we were reaching into a place where we could visualize that. Also, we were inspired by what was around us. Nobody creates in a vacuum.

So we were looking at bands like the Who. And I remember going to see [Scottish pop group] Marmalade at a local gig in Twickenham and hearing those amazing harmonies with the guitar behind it and thinking, How far could you take that? What would it sound like if you went to an entirely new place with it? And we were ready to do that. We just needed to get the canvas to paint on and a decent amount of colors to use.

We had our textbooks – we had the Beatles, we had Jimi Hendrix. We immersed ourselves in those records and figured out how the studio was being used

You didn’t have much studio experience as individuals or as a band, and yet you were able to realize these big, layered productions – “Liar,” “My Fairy King,” “Keep Yourself Alive” – right off the bat. How?

We had some good help. We had [producer] Roy Thomas Baker, who was the technical rock that we could bounce off of. Roy was a very different person in those days. He was highly technical, but not very interested in the art, if you like. But we had the art. We knew what we wanted it to sound like. We just needed someone who could make it happen. Roy was very good at doing that.

Also, we had our textbooks – we had the Beatles, we had Jimi Hendrix. We immersed ourselves in those records and figured out how the studio was being used, how those toys were being brought to bear and how they were employed as an augmentative factor in the songwriting. And, of course, we came along a little bit later, and so instead of 16 tracks we had 24 tracks, and then 48 tracks. We had better compressors, limiters – you name it. We were there, waiting to get our hands on every new toy.

By the same token, your guitar approach is more or less fully formed on Queen. On the very first song, “Keep Yourself Alive,” we’re introduced to the Brian May sound and style that we would hear for the next five decades.

I played then not very differently from the way I play now, I think. I suppose there was this kind of immersion in what we wanted to be, and you can see it in Freddie as well – all of Freddie’s amazing range and power and range of emotions was there, too.

It just needed a chance to get out and be polished. As for my guitar, I could hear the sound in my head, but I couldn’t get it until I went to the Marquee Club on Wardour Street [in London] and saw Rory Gallagher.

My mates and I used to go every Thursday, I think it was, to the Marquee to see Rory, and one night at the end of the show we hid away while everyone was being taken out of the place. Then we snuck out and talked to Rory.

We were just boys, but he was so polite and gentle, like, “Yeah, I’ll show you how I do this.” So I said, “Well, what is your sound?” He told me, “It’s very simple. It’s just this guitar, this beautiful amp” – which was a Vox AC30 – “and this little box here between the two,” which was a [Dallas] Rangemaster [treble booster].

And so I went out and got an AC30, got a Rangemaster, and plugged my own homemade guitar [the Red Special] into it. And glory be, the sound was there! It sang. I had always wanted it to sing, because I wanted it to be my voice. And it sang from that moment on. It hasn’t really changed in all these years. It’s slightly polished up, but it’s the same thing.

You don’t need to spend a fortune on gear – you just need to know what you want and beaver away until you get it

The Red Special, of course, is today one of the most famous guitar designs in rock history. But back then it was just something you and your father had built together in the early 1960s. Add in the fact that you prefer a sixpence for a pick, and that, while you had a Vox and a Rangemaster, you would also occasionally record with a rudimentary amplifier – the “Deacy” – that John Deacon built from parts he found in a dumpster. It’s amazing to think that, given the elegance and high production value of a Queen song, you were using a fair amount of homemade gear.

Well, you know, you don’t need to spend a fortune on gear – you just need to know what you want and beaver away until you get it. And Queen songs, I mean, they are big productions, but I think we were also very conscious that the production wasn’t us – the songs were. We were about conveying emotion and making contact with people.

One of your first major tours, in support of 1974’s Queen II, was as the support act for Mott the Hoople. It was also your first time in America as well. What was that experience like?

It was mind-blowing. I mean, we were kids. We’d never done any of this stuff. We’d spent most of our youth at home dreaming of what it might be like to travel and play music, but what happened was way beyond anything that we could have imagined. And Mott the Hoople were the perfect people to go out with because they were the model of how a rock band can be on tour.

America taught us how to be rock stars, without a doubt. Mott did, too. That’s a big thing to say, but I think it’s true

I remember when somebody told us we were going out in support of Mott, I thought, Eh, they’re not bad, I suppose. I didn’t think of them the way I thought of the Who or Led Zeppelin. But once we went out with them and we were able to see what happened every night and every day, it was like a master class.

Those guys knew how to communicate with their audience. And they knew how to enjoy themselves without being in any way destructive to anyone. They lived the life to the full. We learned a lot every day.

Now, the other thing that was happening on that tour is that people were actually responding to us, which nobody really had anticipated. People started to turn up to the shows dressed how we had started to dress – in the white theatrical costumes and things.

And people of all sexes turned up being very proud of who they were. It felt like a very liberated audience that came to see us, and that in turn allowed us to go out there and learn how to be ourselves. America taught us how to be rock stars, without a doubt. Mott did, too. That’s a big thing to say, but I think it’s true.

On that tour you also experienced severe health issues – you were diagnosed with hepatitis, and you collapsed in New York and had to be rushed back home to Britain. Is it true that you were worried you would be sacked from the band?

Oh, yeah. I also thought I might not pull through at one point. It was pretty serious. I had a very serious condition of the duodenum, and it was by no means certain I would pull through.

Then when I had an operation, it seemed like a very slow recovery, and I thought, Maybe the band needs to move on. But Freddie came to the hospital and said, “Don’t worry, darling, we’re waiting for you.” And then they brought stuff in to play for me, including “Killer Queen.” And I got very critical, being the arrogant person I am. I went, “Yeah, but this is too harsh. You need to redo it.” And Freddie said, “Okay, we’ll redo it when you come out.” And we did.

When I had an operation, it seemed like a very slow recovery, and I thought, Maybe the band needs to move on. But Freddie came to the hospital and said, “Don’t worry, darling, we’re waiting for you”

You said that to him from your hospital bed?

I did. But then they also tried to make me laugh. Because that was one the thing I couldn’t do, recovering from the massive stuff I was recovering from. So it was kind of funny. But not funny for me. It was painful.

You wrote the song “Now I’m Here” [from 1974’s Sheer Heart Attack] about that whole experience – the Mott tour, going to America.

Yes, I did. That song describes the experience of that first tour better than I can do it in words. It’s the feeling of, I think, this kind of Technicolor romp through a new kind of space, a new universe. It was an amazing time for us.

That album kicks off with “Brighton Rock,” which features an extended guitar break that replicates a portion of your unaccompanied solo spot from the Queen II tour.

That’s a rather unorthodox move, and maybe every guitar player’s dream – putting your live solo spot into a studio recording. [laughs] Well, Van Halen did it, a little bit later.

Sure, but “Eruption” was sort of its own thing, rather than something fully inserted into the middle of what is otherwise, relatively speaking, a straightforward rock song.

Again, it was ideas locked up in a bottle waiting to get out. And that whole solo came together live, really. I had wanted to be able to do guitar harmonies onstage, and I thought, How do we do that?

So I did it with delay, taking an Echoplex apart and building a new box with a longer rail and more tape to make a longer delay time. And then I thought, Well, if I have another delay, then I can do three-part harmonies, which are always much better than two-part harmonies… So I built another one.

And that of course opens the door to all this other stuff, because you’re essentially playing a kind of fugue with yourself. So by the time we got to making the Sheer Heart Attack record, I had been playing the solo live, so it wasn’t that difficult for me to go into a version that could be in that song. But it didn’t start off in that song. It started off in “Son and Daughter” [from Queen] I think, on the first tour. But it just seemed to work better in what was then a new song, “Brighton Rock.”

You mentioned Van Halen, which brings to mind one of my favorite solos of yours, from “It’s Late” [from 1977’s News of the World]. You do some two-handed tapping in that, about six months before “Eruption” was released.

Yeah, I picked it up from… I wish I knew who it was that I saw. I went into a bar in Texas when we were on tour, and I saw this guy playing. And he would be bending strings, like we all do, but then he’d put his right hand onto a fret and make this kind of singing sound. And I thought, Oh, that’s a beautiful thing to do; he creates a completely new dimension.

I went up to him after the show and I said, “I’m telling you now, I’m going to nick that from you.” He said, “Great, go for it.” I asked him, “How did you figure out how to do that?” And he told me, “I got it from Billy Gibbons.” Now, I ought to talk to Billy about it, because I can’t put my finger on the piece where Billy did it. But somewhere in the murky past, somebody thought up that technique.

It was questionable sometimes whether that could all be contained under the umbrella of what Queen is. But somehow we were able to do it

Did you ever talk to Eddie about it?

I did talk to Eddie about it, and he said, “Yeah, I copped that.” [laughs] But I think he was already onto it. Strangely enough though, I recently came across a live recording of Van Halen doing “Now I’m Here.” It’s great. They’re sort of doing us. And I think the blurb that went along with it online said something like, “Edward hadn’t developed his style yet.” But I don’t agree.

You listen to what he was doing and he’s already him. He’s already doing his own thing. But he’s doing it on my song, which makes me very happy.

Those early Van Halen live recordings and demos are available online, and I would agree with you – he sounds exactly like the Eddie we all know and love.

Oh yeah, genius. He was genius from birth, I think. And he’s no longer around, which is so painful, so hard. I just wish he was here.

We could explore any frontier. And we’re lucky that we have an audience that has allowed us to do that

Looking at Queen’s career more broadly, one thing that I’ve always felt sets the band apart is the diversity of the music. For some people, “Bohemian Rhapsody” is the defining Queen song. For others it might be “We Will Rock You” or “Killer Queen” or “Another One Bites the Dust.” And yet, each tune could be the work of an entirely different group in terms of sound and style. How were you able to shapeshift so expertly while at the same time maintaining a distinct “Queen-ness”?

Probably because we had four writers competing for rotation. We had a collective vision, but we also had visions which were uniquely personal. Also, there was a realization at a certain point that we could do anything we like.

We could explore any frontier. And we’re lucky that we have an audience that has allowed us to do that. They didn’t want to put us in a box. So the writing is a big part, but there were some points where we would question it, particularly with Roger and John, who were at opposite ends of the spectrum.

John was very much leaning toward funk from the beginning, whereas Roger was leaning toward the more extreme end of rock and roll. And it was questionable sometimes whether that could all be contained under the umbrella of what Queen is. But somehow we were able to do it. And somehow it all counted, and all became part of us.

To that point, it’s amazing how “what Queen is” continues to be redefined. For example, “Don’t Stop Me Now” [from 1978’s Jazz] was not a huge hit, and yet it has become one of your most popular songs, with close to a billion listens on Spotify.

It’s a phenomenon, that song. I’ve seen it played at all sorts of functions. It’s become the most requested song at hen parties and stag parties and marriages and weddings and funerals, just because it brings joy. And I think this is well known, but I didn’t really take to it in the beginning. I didn’t feel totally comfortable with what Freddie was singing at the time.

I found it a little bit too flippant in view of the dangers out there of AIDS and stuff. But as time went on, I began to realize that it gave people great joy. So I don’t think you need to look any further than that. And I think that’s what Freddie had the amazing knack of doing. He could put his button on things that make people feel a bit more alive. So I don’t have any quarrel with it now. And I enjoy playing it onstage.

I just put a little bit of extra rock in it, ’cause that’s the way I am. You can hear it on our new album, Live Around the World, and the audience is so loud singing along that it was hard to even mix it. But it’s wonderful that everybody wants to sing that. And in singing it with us, they express their own joy and their own determination to make the best out of their lives, and to keep on and not get knocked down by things. It’s an amazing kind of spiritual lift. That’s what the song has become.

It’s remarkable that a song you once viewed as dangerous has become, interpreted through the lens of your audience decades later, a life-affirming statement.

You know, I had to give in. [laughs] It’s a great song – there’s no getting around it. It moves people, makes them smile and jump up. What more could you ask for?

I know you get asked this a lot, but could you ever see a new Queen record happening?

I always say, “I don’t know.” It would have to be a very spontaneous moment. Actually, Adam, Roger, and myself have been in the studio trying things out, just because things came up. But up to this point we haven’t felt that anything we’ve done has hit the button in the right way.

So it’s not like we’re closed to the idea, it’s just that it hasn’t happened yet. And to be honest, life has now taken a turn in which it’s very difficult to explore an avenue like that. Things may change, but I don’t think they’re going to change very fast.

Until you can play your guitar on a stage again, you’ve kept yourself busy on social media. Over the past year I’ve watched you give lessons on how to play the “Bohemian Rhapsody” solo, perform virtually with guitarists like Nuno Bettencourt and Zakk Wylde, and also jam with Queen fans around the world. I’ve even seen you take part in a TikTok challenge. You’ve been visible in a way that I imagine is very heartening to your fans. And you also seem incredibly comfortable operating in the online world.

Well, I’m a performer, and performers are all struggling to be heard, aren’t they? And in this new situation that we’re in now, the only way to be heard is on the social media sites. And so Instagram has become a little platform for me to play on.

I don’t get instant applause, but I get a lot of response in the comments, and I get people actually participating. People take up the challenge of jamming along with me, and then they put it out there so I can see it. It’s very interactive. So it’s great. Sometimes I look at it and I think, Yeah, that’s become what I do.

I’m working on various different projects with different NASA teams, and I’m editing a new book on the birth of stereoscopy. So it’s not like I’m stuck for things to do with my time

After 50 years, that’s sort of a wild place to wind up.

It is. Now, I do other things as well. I’m pretty deeply into science, as you probably know. I’m working on various different projects with different NASA teams, and I’m editing a new book on the birth of stereoscopy. So it’s not like I’m stuck for things to do with my time.

Also, I had real physical problems last year. I had a long period of being out of action because of a heart attack, and various weeks of repercussions that came after that.

But at the heart of it, I’m a musician and I need to play. And in a sense, I suppose, I need to see people’s faces. I need to feel that I can get a response and do the thing that musicians do, which is communicate. Right now, the only thing that is different is in the way we do it. But other than that, it never changes.

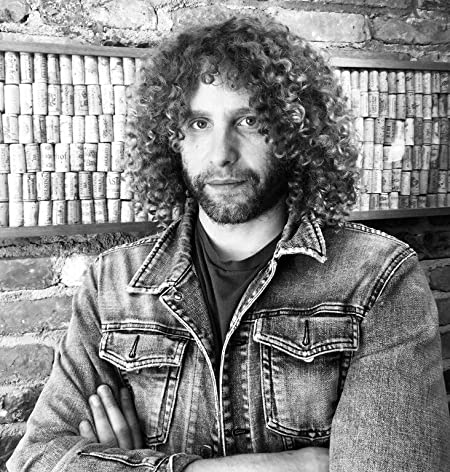

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.