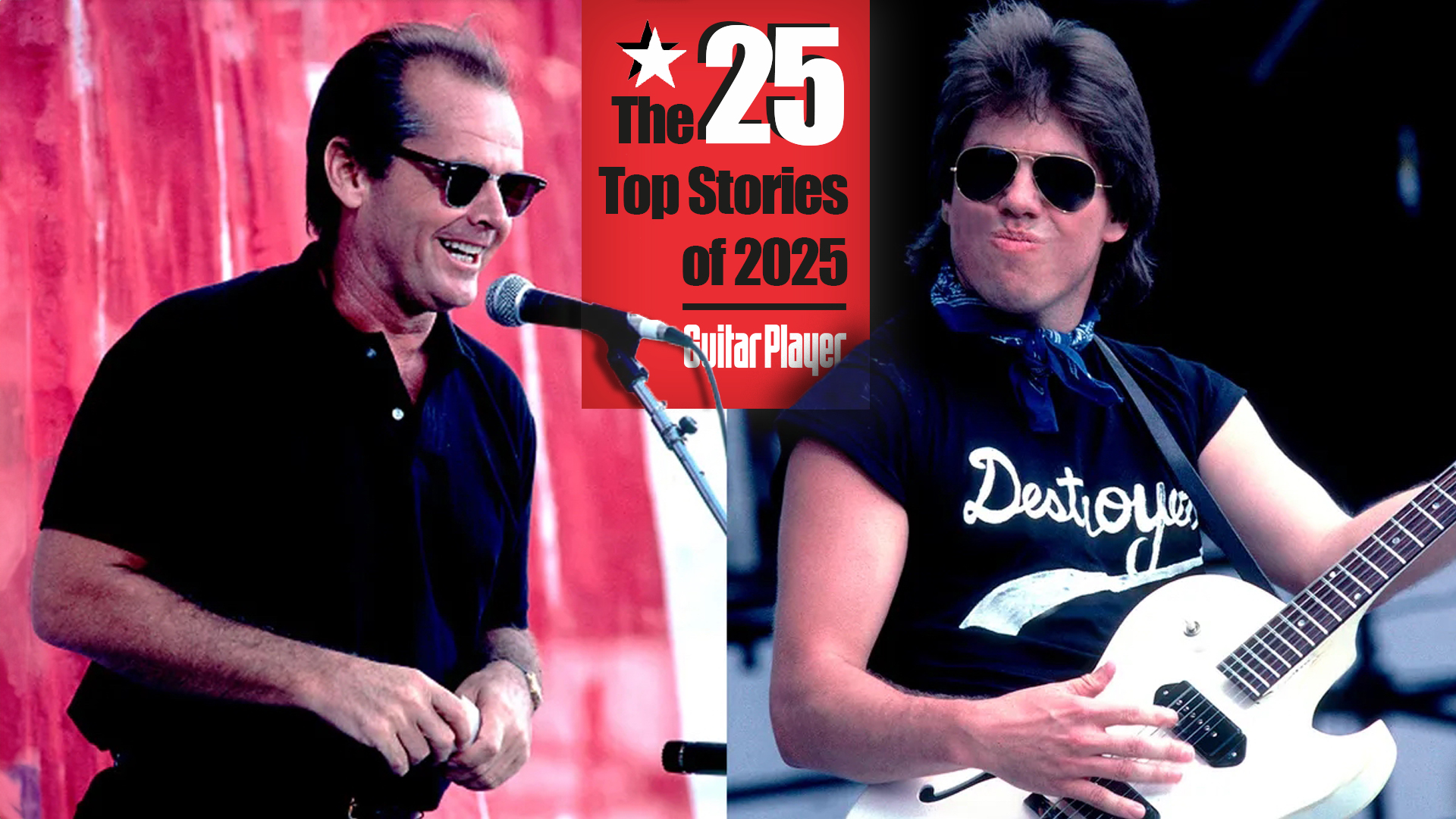

“I’m in Two Great Bands, so It’s Complicated”: Nils Lofgren Reflects on His Tenure With Neil Young, His New Tour With Bruce Springsteen, and His Latest Obsession: Pedal Steel

The rock ‘n’ roll veteran reveals what’s going on behind the scenes as Crazy Horse drop their latest, ‘World Record’

It’s early – barely past sunrise – in Nils Lofgren’s area of Arizona, not far from Scottsdale. But the veteran multi-instrumentalist is awake and into his day, accompanied by Rose, the 95-pound mixed-breed Lofgren and his wife, Amy, rescued last year. She and the couple’s 14-year-old Chihuahua, Outlaw Pete, meanwhile, are still asleep.

“I like getting up super early, sometimes in the dark,” Lofgren, 72, says. “When I’m on the road it’s different; I can’t sleep because of the performance adrenalin. But at home, when I’m able to get a little sleep, I’m an early riser.”

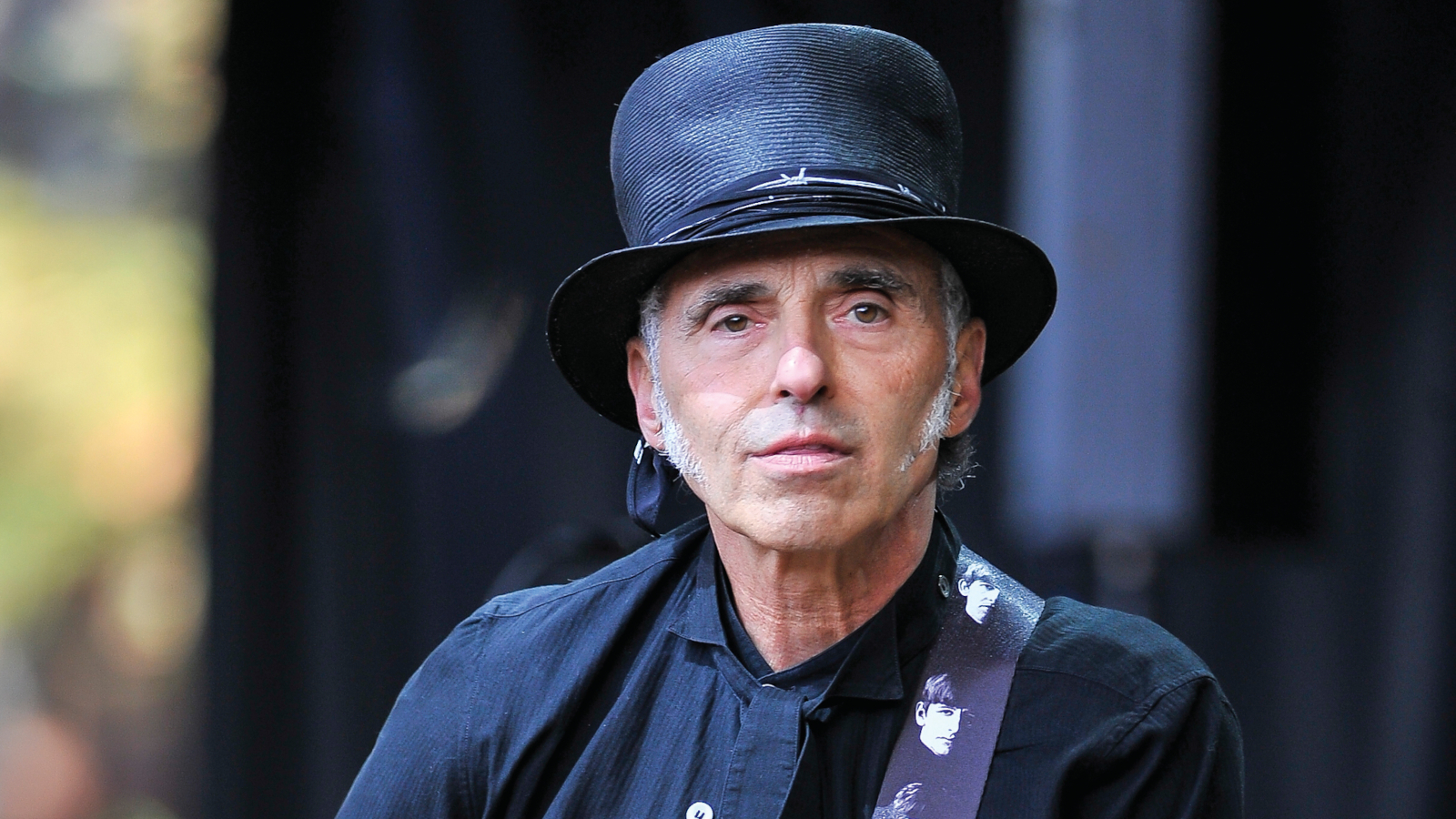

Lofgren isn’t one to waste any of that time, either. He’s been a recording artist since he was a teenager in the band Grin – which got its break thanks to the patronage of Neil Young and his co-producer, the late David Briggs, who made Lofgren part of Crazy Horse for 1970’s After the Gold Rush.

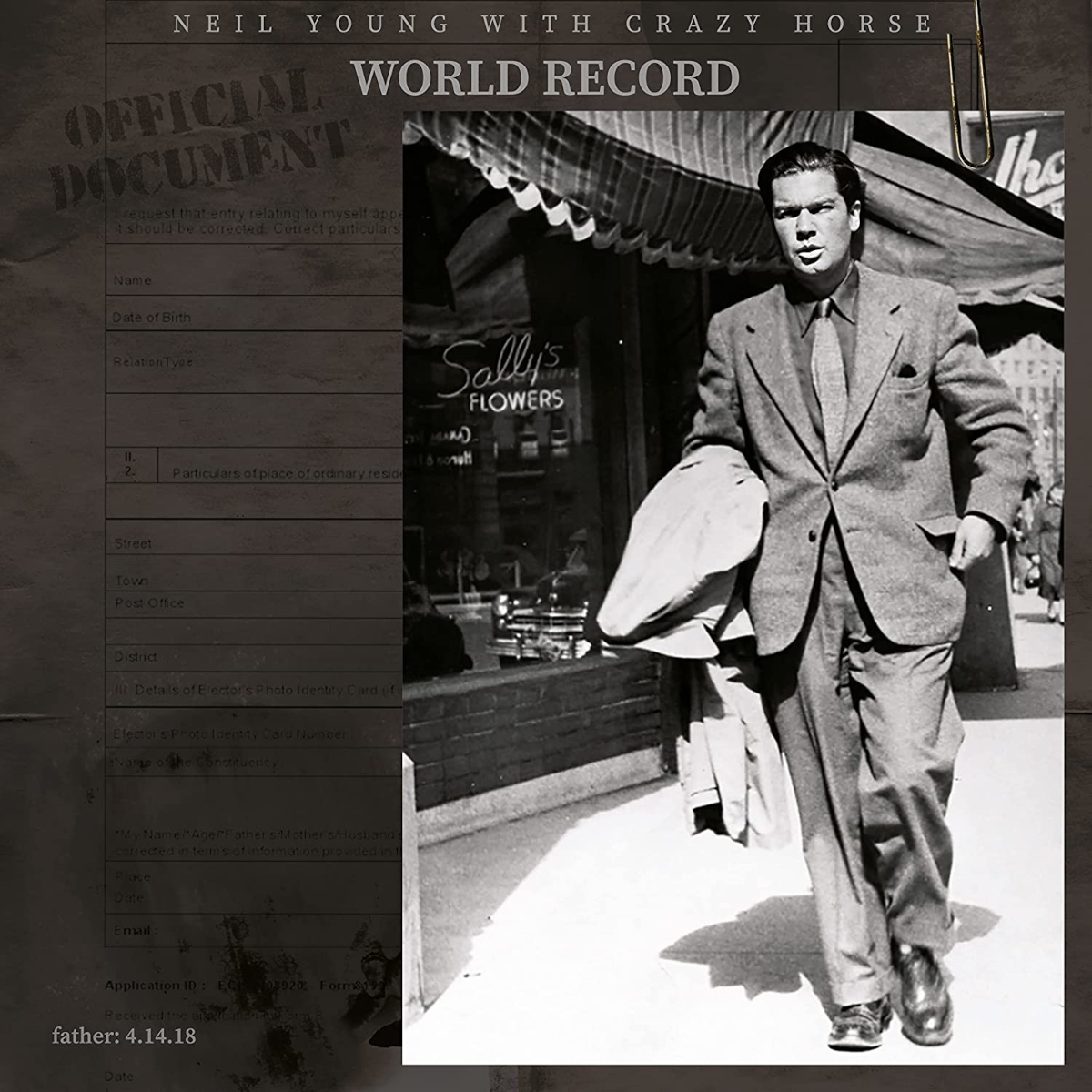

Lofgren is now in the midst of his third tour of duty with Crazy Horse, back in the saddle since 2018 and Frank “Poncho” Sampedro’s retirement from the group. He’s made two pandemic projects with the band: Barn, recorded June 2020 in, as the title indicates, a converted barn, dubbed Studio in the Clubs, in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains; and World Record, released this past November, made with Rick Rubin at his Shangri-La studio in Malibu.

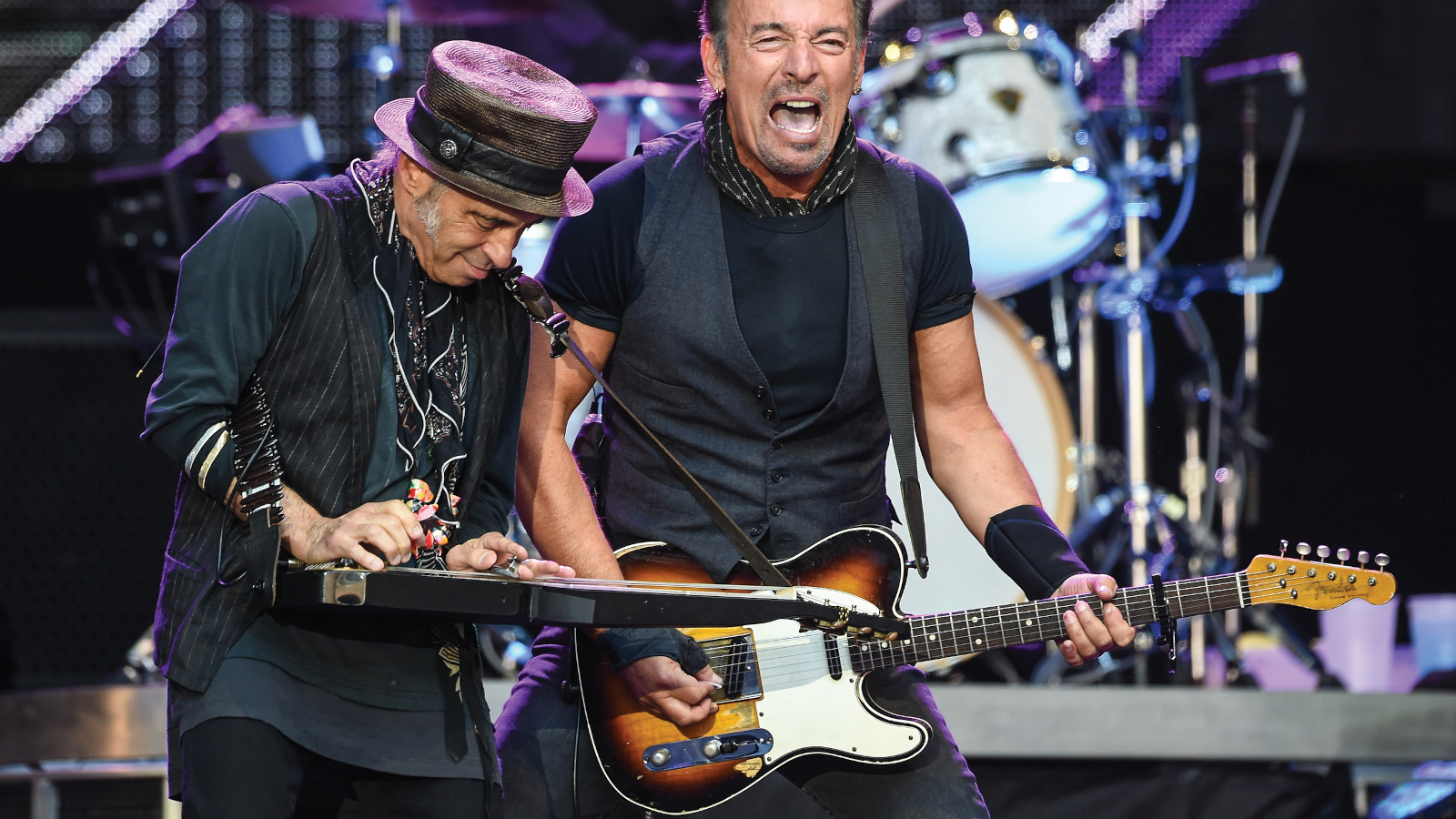

Lofgren has also logged a solo career that he began with a self-titled effort in 1975 and has been part of the E Street Band since replacing Little Steven Van Zandt in 1984, playing on eight of Springsteen’s studio albums.

He served tours of duty with Ringo Starr’s first two All-Starr Bands, co-wrote with the late Lou Reed on 1979’s The Bells (along with songs that became part of Lofgren’s 2019 album, Blue With Lou), and he was the lead guitarist on onetime Foreigner frontman Lou Gramm’s first solo album, Ready or Not, in 1987.

Stalwart is a more fitting term for Lofgren than journeyman, and given his multi-instrumental skills – guitar, keyboards, accordion. banjo, pedal and lap steel, mandolin – virtuoso is not out of the question.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He spoke with Guitar Player just as World Record was rolling out and Springsteen began tuning up to hit the road…

It’s been a long time since you’ve done any touring. What are your expectations for this year?

We’ve got a great body of work, so you brush up on it. Bruce has a new album of his favorite soul and R&B songs [2022’s Only the Strong Survive], and it’s obvious that’ll be in there. But, y’know, we’re used to improvising, never following a set list, which is something Neil doesn’t follow either.

I think the last show we played with Neil, up in Canada, it was 20 minutes before the show and we were waiting for a set list we know we will not follow, and Neil just said, “Guys, I don’t want to write a set list. Let’s just walk out and do whatever comes.”

That’s extraordinary, to be able to walk out with no set list and just wing it. And it worked out great ’cause it’s Neil and Crazy Horse.

Same thing with Bruce – there’s a lot of improvisation. So I just get ready like I always have and hope for the best that it works out.

You like it unpredictable, don’t you?

It’s not for everybody. It’s like the difference between a classical musician, who can sightread the most complicated thing you put in front of them and play it, but if you asked them to improvise the blues they say, “No, I don’t do that.”

I’m blessed to be part of two really great bands. And occasionally I’ve been lucky through the years to moonlight with Willie Nelson and Branford Marsalis and other great people

Nils Lofgren

I studied classical accordion for 10 years, from five to 15, then picked up the blues guitar as a hobby, just ’cause all my heroes were, like, B.B. King, Albert King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, Clapton…all of ’em. And I was just playing it for fun, never thinking I could be a professional musician.

You have your solo career, of course, but you’re such a band guy, too. Do you have a preference?

I’m lucky to have both, and I’m blessed to be part of two really great bands. And occasionally I’ve been lucky through the years to moonlight with Willie Nelson and Branford Marsalis and other great people.

And it was probably a blessing I didn’t have a hit record when I was 18. It might have killed me and would certainly have precluded going out with other great bands. But I still remember when I was 18, walking into David Briggs’ home in Topanga and driving his little VW to Neil’s home to record After the Gold Rush. I still remember saying, “Wow, it’s nice not to be the bandleader.”

All these nonmusical responsibilities disappear and everything is just musical. I just embraced that, and I still do.

You made an album with Springsteen that came out during the pandemic [2020’s Letter To You], but it’s Crazy Horse that kept you busiest, between Barn and World Record, which were two very different recording experiences.

For sure. We had a ball making Barn, and there was a great, very earthy, realistic documentary [Barn, directed by Young’s wife, Daryl Hannah] of friends for 50-some years. And as we kept going through Barn, of course, we talked about touring, and we wanted to play, but COVID kept that from happening.

But Neil talked about writing again, and he would keep in touch with us. And at one point he said, “Hey, it might be summer, maybe a little earlier.” Then out of the blue he said, “Look, I have the songs, can you make May 1st work?”

He didn’t exactly have the songs like he used to, though, did he?

I was surprised. I’m used to working pretty quickly with Neil, especially when it’s Crazy Horse. Usually it’s 11, 12 days – a kind of a whirlwind, catch-it-as-you’re-learning, super-live, no-headphones approach, which is really cool.

I’m used to working pretty quickly with Neil, especially when it’s Crazy Horse

Nils Lofgren

And all of a sudden he said, “We’re gonna probably be 21 days, because I need some time to figure out what I’m gonna play. I wrote these songs walking and kind of singing, chugging, rapping, whatever into a Dictaphone. So I need some extra time.”

What was that figuring-out process like?

It was this organic, beautiful thing that we did. It was an exploratory thing. The songs weren’t full arrangements that were mapped out.

Billy [Talbot, bassist] and I were at least on top of some chord progressions, but Neil didn’t know what he was going to play from song to song. He kept jumping from instrument to instrument, and so did I. I’d go to the pump organ or the accordion; he’d pick up a guitar or go to the piano.

It was kind of musical chairs sometime, and days sometimes before we figured out what he and I should play for each song. ’Cause he said, “I’ve never written an album without an instrument.” It was a very fresh, very new kind of thing for us.

When most people think of Crazy Horse, they think of Tonight’s the Night or Rust Never Sleeps or Ragged Glory – the grungey, distorted guitar stuff. But when you’re involved, it tends to be gentler and more subtle. Are you the guy that tames the beast?

[laughs] I don’t know. Certainly, the obvious nuances, the different instruments and the accordion and any keyboard are what I add to it. Also, just the tonality of my singing.

Y’know, the band’s got an enormous history of great stuff and what Danny [Whitten] and Frank did. Poncho did an amazing job for 37 years, especially the heavy rock and grunge sound. But it’s obvious that when I’m in the band we’re able to jump around and have more sounds and be more nuanced.

But the heavy thing – that sneaks in here and there with me too.

The heaviest moment on World Record is “Chevrolet,” another long, 13-and-a-half-minute guitar epic. How did that come about?

When I heard it I thought, Yeah, this’ll be a great two-guitar track. I got out the black [Gretsch] Falcon and cranked it way up to where it was starting to take off in my hands a little bit, not unlike Neil and Old Black [Young’s customized 1953 Les Paul].

I’d overdriven the sound and turned it way up, and it really had a great sound with Old Black. And all of a sudden we were playing it, and we got into this hellacious, long jam. I think it was like 14, 15 minutes.

Neil called me about it later and he said, “Y’know what? We got the single edit, which is only 11 minutes, but we put three minutes back in ’Chevrolet.’” I said, “Great!”

I got out the black [Gretsch] Falcon and cranked it way up to where it was starting to take off in my hands a little bit, not unlike Neil and Old Black

Nils Lofgren

It definitely has the live, off-the-floor feel we associate with Crazy Horse. Was that the case?

We kept trying it. We’d just come in every couple days and play the song again, just two or three times, and move on, and I think they used one of the earlier ones for the album.

There was one time where it got really crazy. Neil was playing lead and I started doing some counterpoint, and then it just smoothed out into the groove. I said, “Well, that sounds like you went into a rough town and had a lot of misadventures, and now you’re back on the highway, just cruising at 45, taking it easy.”

I like that. I thought it was a great thing and a bit of self-discovery as a band.

You’re playing pedal-steel now, I see.

For the first time, yeah. I’m kind of a beginner pedal-steel player. I got to spend so much time with the great Ben Keith on the road and in studios, way back to Tonight’s the Night. He was such a great inspiration to me.

So there’s a couple songs I played pedal steel on for the first time forever, which for me was a kick

Nils Lofgren

I’m still kind of a decent beginner on it, but when we were gonna do “I Walk With You” I had it in my room and ran it through this little [Electro-Harmonix] POG that makes it sound like a pipe organ that’s being distorted, ’cause I didn’t know what to play on that song and I didn’t want to just crank up the black Falcon and have it be a rough guitar.

I thought, Man, the pedal steel, if I overdrive it through this little POG…. And I said, “Neil, can you come in my room?” I played the sound for him and he said, “Man, you got to get this instrument over in the main room,” which I did.

So there’s a couple songs I played pedal steel on for the first time forever, which for me was a kick, because as a beginner you’re a little cautious. It’s not like improvising the blues on a Strat, but it worked.

Sometimes knowing a little less turns into more, because you have to compensate for what you don’t know.

I remember on After the Gold Rush, when they asked me to do it, I was 18. They said, “We’re gonna put you on piano, too, as well as guitar and singing.” I said, “Well, I’m not a professional piano player,” but they were like, “Yeah, but you played accordion your whole life. You’ll come up with something good.”

And I just did these simple parts and they worked. At my most creative, I was very deliberate and simple, and that left a lot of space that was appealing to David Briggs and Neil. That’s something I’ve never forgotten.

Rick [Rubin] was helpful in kind of giving me some tips, or old records to check out, just for a general place to aim at, ’cause we had a million instruments

Nils Lofgren

What was working with Rick Rubin like for Crazy Horse? It seems like it could have been a Godzilla versus Mothra situation, since Neil tends to like to keep hold of the reins on his albums.

I think Neil in general is reticent to turn over that type of control, but I think this time he just wanted to show up and just be the guitar player and the singer and not always have that producer’s hat on. Rick allowed that for him, and it worked really well.

I got there early, so I saw Rick one afternoon, sitting in the sun on the porch. I went up and we had a nice chat about music and history. He learned a lot about me, I learned about him. And Rick was helpful in kind of giving me some tips, or old records to check out, just for a general place to aim at, ’cause we had a million instruments.

We had so many options it was unreal. Everyone was wide open to anything and everything. Obviously, the main goal was to come up with something that they both felt good about.

You’ve got a full schedule with Springsteen this year. What happens if Neil decides to take Crazy Horse out, too?

[sighs] I’m in two great bands, so it’s complicated. I’d love it if Neil and Bruce let me make their touring schedules so I could weave back and forth in both bands, but of course no one’s gonna let me do that, so I just do the work that’s in front of me.

And if Neil goes out and has to get somebody else, that’s how it’ll have to be, y’know?

If Neil goes out and has to get somebody else, that’s how it’ll have to be, y’know?

Nils Lofgren

Are you working on another album of your own?

I am, and you know what? I’m pretty far along. I’m feeling really good about it. It’s got rough stuff, gentle stuff. I’m not in a rush. I’ve been chipping away at it all year. I’m hoping to be done by the end of the year and maybe get it out in the spring.

It’s just this little mom-and-pop operation my wife, Amy, and I have [Cattle Track Road Records]. We’ve been doing that since the early ’90s, when I parted ways with the music industry. And it’s very healthy for me to do my own music.

It doesn’t replace performing, but it gives me a creative outlet, and I’m excited about the record.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.