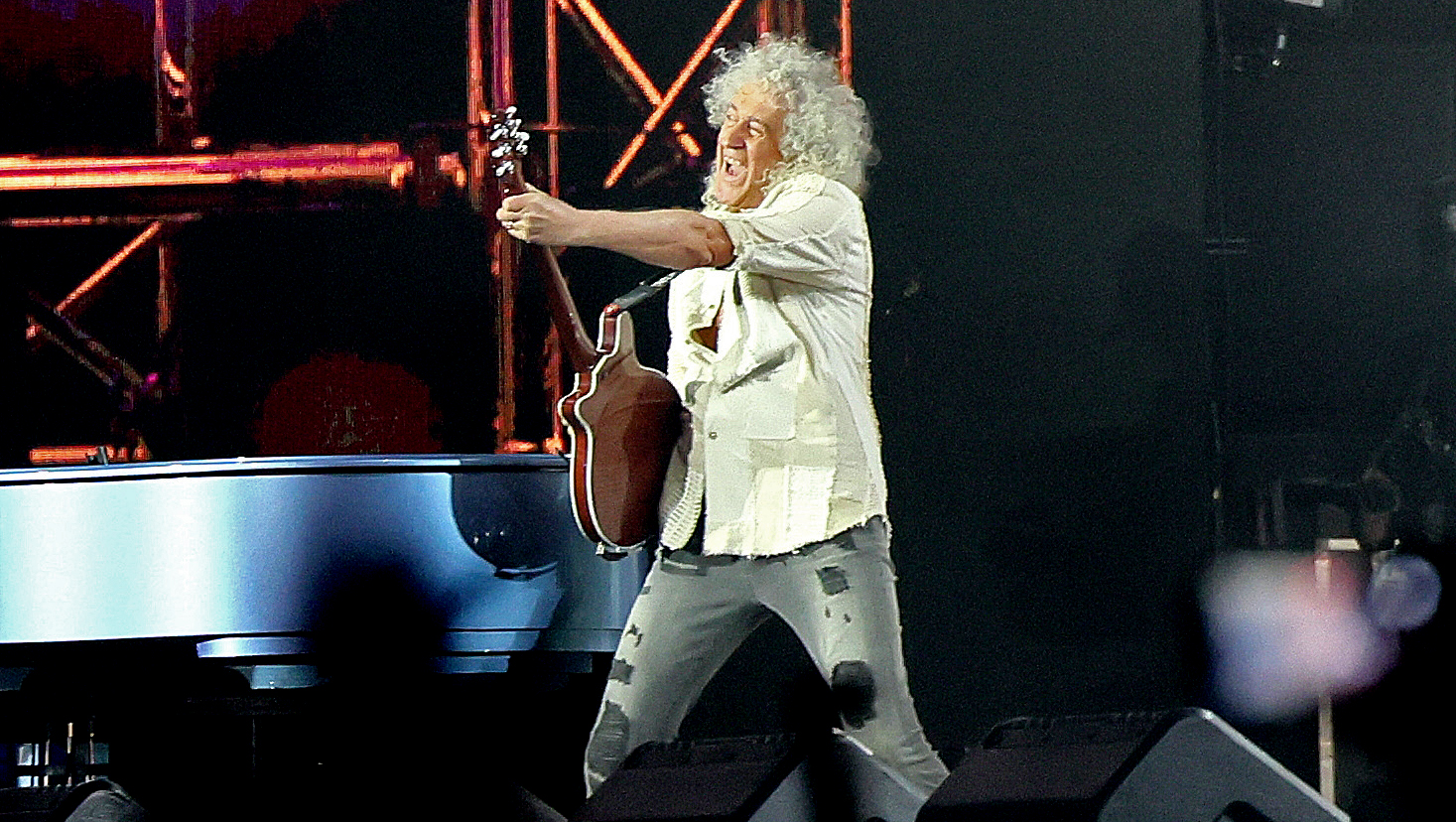

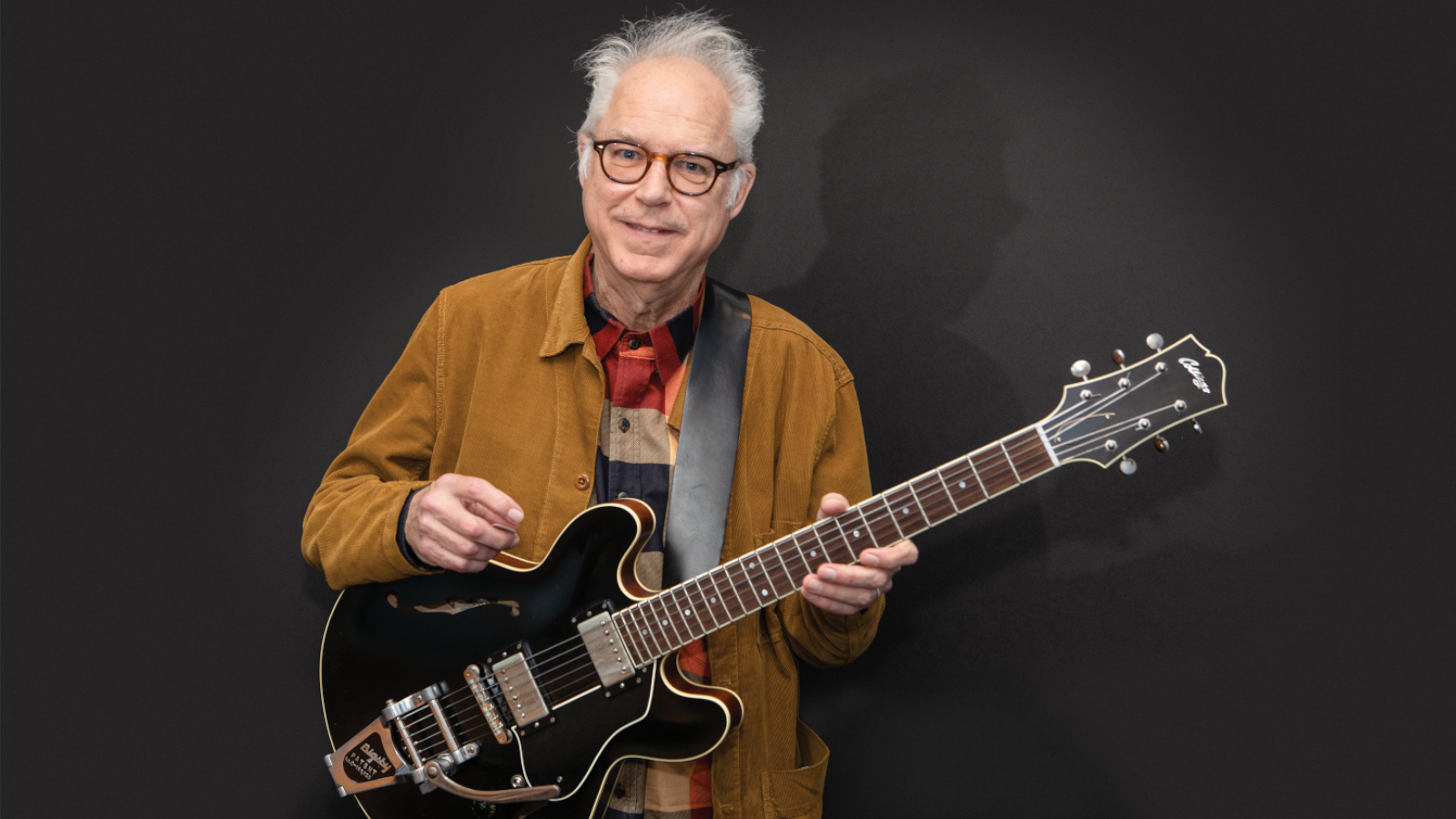

“Every Note Is a Question”: Bill Frisell Reveals the Approach That Helped Him Become Guitar’s Most Sought After Player

‘GP’ asks a few questions of our own in this essential interview with one of the greatest jazz musicians of our time

When the Beatles made their American debut on The Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964, it inspired a generation of Boomers to pick up the guitar. But it was a much earlier TV broadcast that helped turn Bill Frisell on to the instrument, when he was a boy growing up in Denver.

Credit Jimmie Dodd, host of The Mickey Mouse Club, with planting the six-string seed in Frisell’s young brain. Dodd was Head Mousketeer during the televised show’s initial 1955 to 1959 run, when it was shown five days a week on ABC stations across the country. He wasn’t just an actor; Dodd also wrote the program’s theme song and premiered his Mousegetar on the November 11, 1955 show, which aired just a few months before Frisell’s fifth birthday.

Dodds’ adeptness on the instrument was immediately evident in the crisp, Django-esque filigrees he played between strummed chords on the tune “I’m a Guitar.”

It may have been that very song that first captured the imagination of young Billy Frisell. “Right there is what got me wanting to play the guitar,” Frisell tells Guitar Player. “I think I was about four. Wow!”

Frisell’s guitar journey followed a path that began in earnest at age 13, when he took lessons with Bob Marcus at the Denver Folklore Center. In high school, he got hooked on Wes Montgomery and as a senior began studying guitar with Dale Bruning, who recorded a series of jazz standards with Frisell decades later on their 2000 duo album, Reunion.

At Colorado State, now the University of Northern Colorado at Greeley, Frisell studied for one semester with jazz guitar great Johnny Smith, whose clean articulation and impeccable picking technique on 1956’s Moonlight in Vermont, with sax great Stan Getz, had also influenced young Pat Martino.

Smith’s 1962 solo guitar album, The Man with the Blue Guitar, recorded at his Johnny Smith Guitar Center in Colorado Springs, may have served as a template for Frisell’s own 2018 solo guitar debut, Music IS.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

To date, Frisell has made more than 40 albums as a leader, starting with 1982’s In Line for Manfred Eicher’s ECM label. Prior to that, he had served as a kind of house guitarist for the imprint, appearing on albums by German bassist Eberhard Weber (1979’s Fluid Rustle), American drummer Paul Motian (1981’s Psalm), Norwegian bassist Arild Anderson (1982’s A Molde Concert) and Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek (1982’s Paths, Prints).

He has since racked up appearances as a sideman on more than 300 recordings that cover a remarkable range of artists and styles. He’s cut pop and rock sessions for the likes of Elvis Costello, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Marianne Faithfull, Rickie Lee Jones, Bonnie Raitt, Joe Jackson, Loudon Wainwright III, and Robert Plant and Alison Krauss.

He’s accompanied jazz legends like pianists McCoy Tyner and Paul Bley; bass players Ron Carter and Gary Peacock; trumpeter Chet Baker; drummers Jack DeJohnette, Billy Hart, Ronald Shannon Jackson and Andrew Cyrille; and saxophonists Charles Lloyd and Lee Konitz.

Some of Frisell’s most potent and revered recordings came as a member of the bass-less trio featuring saxophonist Joe Lovano and led by the late jazz drummer-composer Paul Motian, with whom he made 20 albums during their more than 30 years performing together.

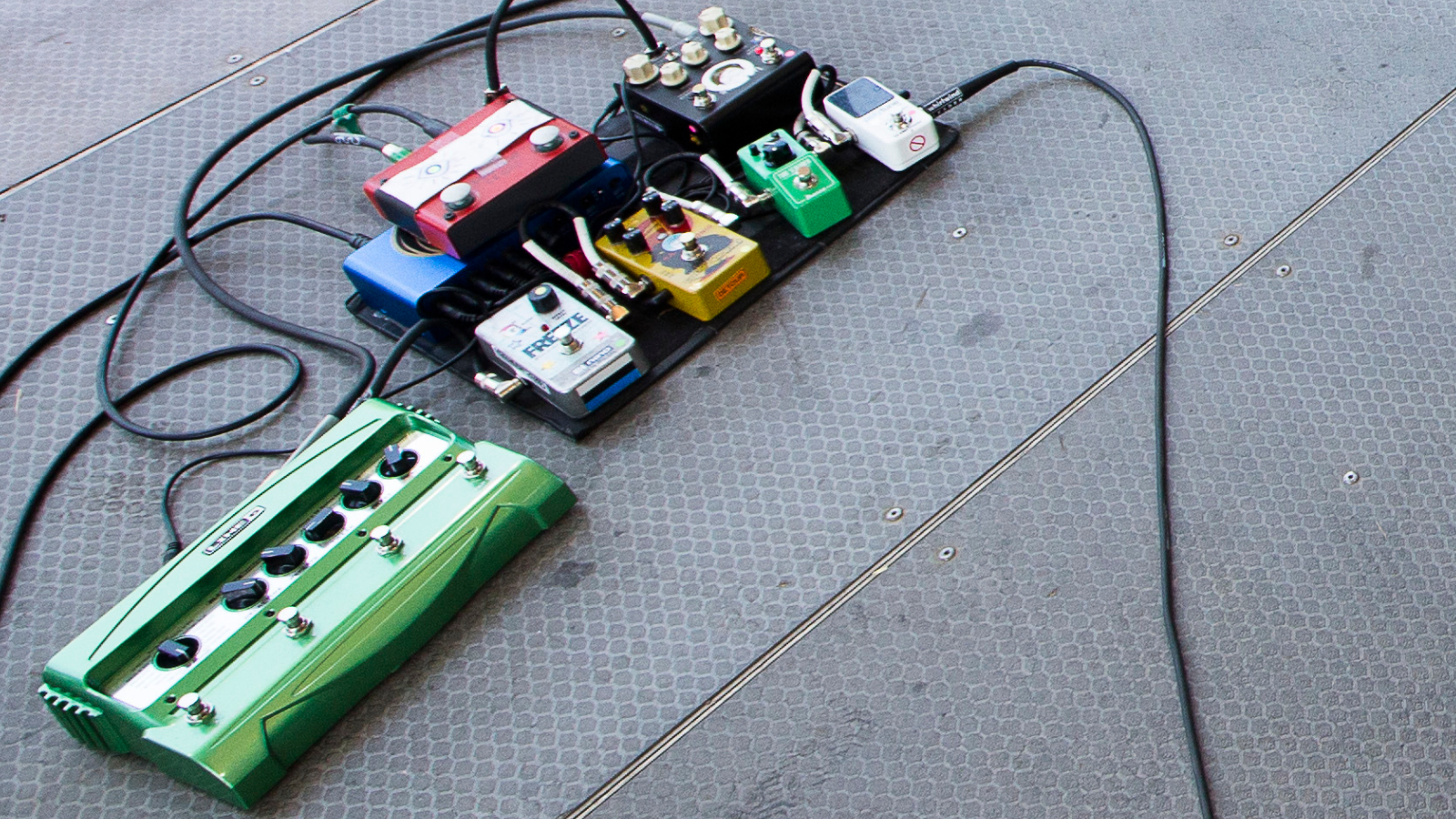

Frisell was also a pioneer of the current craze for looping. He pioneered looping-delay-backward effects in the ’80s, then in the ’90s had some edgy encounters with distortion pedals during his time in the services of John Zorn’s cacophonous avant-noisecore improv band, Naked City.

He’s famously known for using the Electro-Harmonix 16 Second Digital Delay early in his career before switching in 1999 to the Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, the looping pedal that has remained in his arsenal ever since.

Frisell has cut back on effects considerably in recent years, allowing his innate musicianship and melodic gifts to shine through with stunning clarity and intention. As ever, what he plays is surprising, rendered with a tasteful, painterly approach.

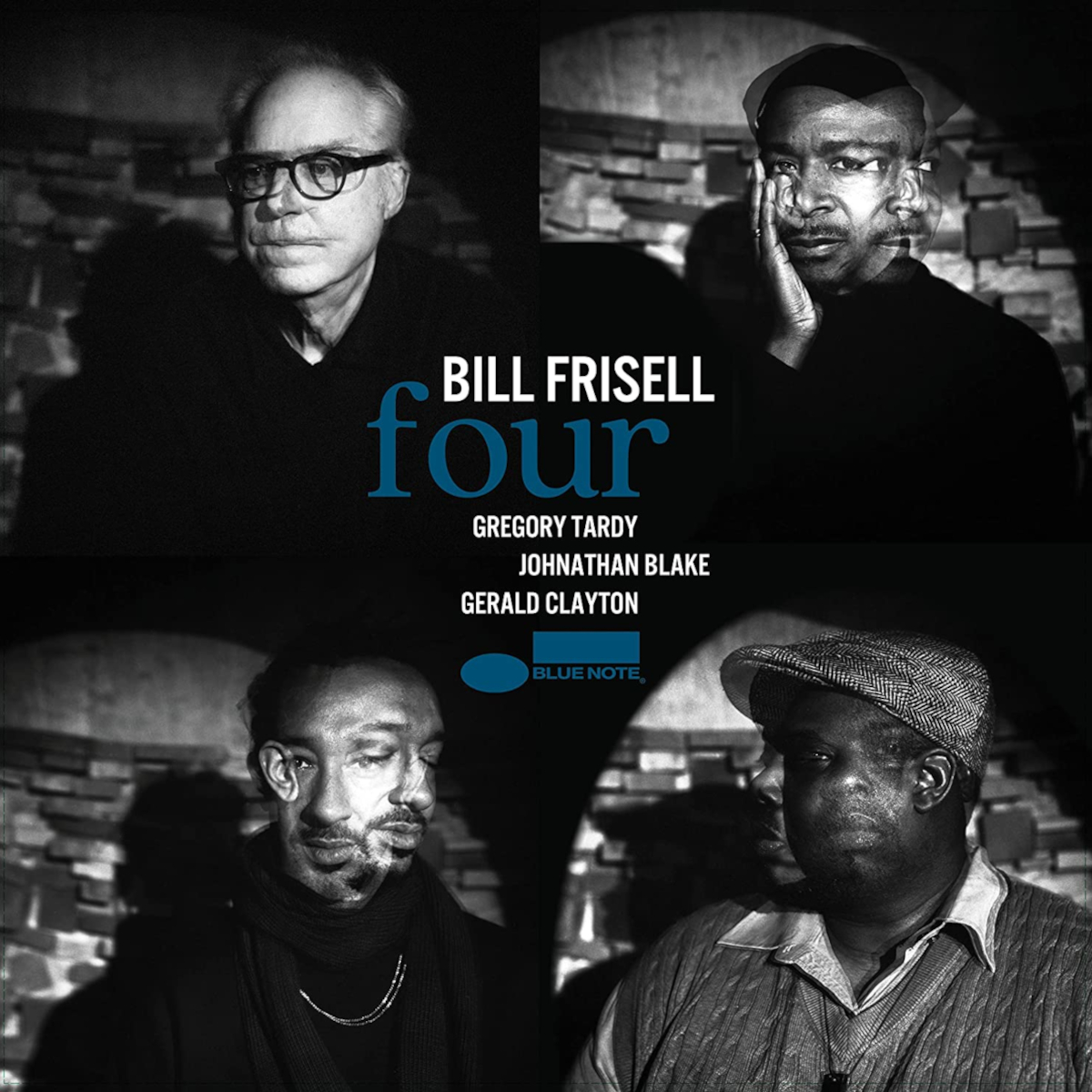

GP talked to Frisell about his latest Blue Note release, 2022’s Four, with pianist Gerald Clayton, saxophonist-clarinetist Greg Tardy and drummer Johnathan Blake. He also shed light on his philosophy of the instrument, his approach in a band setting and his current arsenal of guitars, which includes a blue Telecaster that belonged to his late friend and colleague Robert Quine, who made his mark with proto-punkers Richard Hell & the Voidoids (their 1977 album, Blank Generation, is a definitive anthem for that era) and during the early ’80s with Lou Reed (circa Blue Mask, Legendary Hearts and Live in Italy).

In Philip Watson’s recent biography on you, Beautiful Dreamer, he brings up your meeting with Robert Quine in the early ’80s at music journalist Chip Stern’s apartment on the Upper West Side. So essentially, we have Chip to thank for bringing you and Quine together, which led to your early experiments with the Electro-Harmonix 16 Second Digital Delay pedal. And the rest is history.

Yeah, Chip was right there when Quine brought it to a jam we had. And as soon as I saw it working, it was sort of this instantaneous thing. I just knew what to do with it. It was like it was made for me or something. And Quine was sort of amazed when I started playing it. His mouth was hanging open just watching me play. I swear, it was like... Somehow it was just all laid out. It just fit with the way my brain was working.

You’ve done so much over time with looping and backward guitar. But on the new album, Four, you only dial up looping on one tune, “Dog on a Roof.”

Well, I thought I was going to make it through the whole record without using that thing. I’ve been using it less and less lately.

I’m sort of getting pretty burned out on effects. The last few months I haven’t been using anything at all

Bill Frisell

Your 2019 album Valentine had some backward effects on it.

Yeah, a little bit. But the last few months of being out there playing, I haven’t used any effects at all. Reverb is about the only effect that I’m using these days.

What pedal do you currently use for looping?

It’s a Line 6 DL4 pedal. I had the Electro-Harmonix 16 Second Digital Delay for quite a while before that bit the dust. Then I had a DigiTech 8 Second Delay, which was also another thing that Quine introduced me to. He always was the first guy to get that new stuff. Then I got the Line 6, and that’s pretty much been it for me for 20 or more years.

But really, I’m sort of getting pretty burned out on effects. The last few months I haven’t been using anything at all. I did a solo gig a couple of months ago, and that’s the kind of situation where I always would rely on it so much. But I was proud of myself: I did the whole gig without using any pedals or anything, just playing by myself. That was sort of the true test, I guess.

It affected the way I hear structures in the music, so you carry that over into how you play without them. So if you take the box away, the effect is still in your imagination. Now it’s almost like I’m trying to get at some of that stuff that I would have done with the delay, but I’m just doing it with my hands.

You’re emulating the effect to the point where it becomes part of your vocabulary.

Yeah, which is kind of great. It’s like you learn something from the machine. It will teach you something that you figure out how to do yourself.

I went back and listened to your first album from 1982, In Line, and that is a startlingly singular statement at that moment. On the title track, for instance, there’s layers of guitars, lots of loops, no discernible time. It’s like a different language for the instrument back then, and it sounds as amazing and refreshing today as it did 40 years ago.

Wow. I haven’t listened to that in so long.

And that debut album introduced a tune that you would continue to play over your career, “Throughout.”

Oh, yeah. I feel like that was sort of the first song that I ever wrote that was like an actual bit of inspiration. It just came out in a couple seconds. I don’t know how that happened and I keep trying to get back to that. Something like that happens and you think, Man, it’s so easy to write a song. But then it’s like, Okay, try to write another one.

On the new album, you reprise your compositions “Good Dog, Happy Man,” “Monroe” and “Lookout for Hope.” What is your attitude about approaching your own tunes that you had previously recorded before?

As I get older, I notice that happening more. For example, I first tried to play “The Days of Wine and Roses” maybe 50 years ago, and as the years go by you keep discovering more and more about the tune. It keeps revealing more and more stuff. So I was aware of that happening with standard tunes.

With anything I write, I don’t have any hard and fast idea of what it’s supposed to be

Bill Frisell

But what’s weird about getting older, it starts happening with my own tunes. So if I come back to one of my own tunes that I haven’t played in a while, I’ll see it in a completely different way or I’ll notice things that are in it that I didn’t even know were there before. In this case of playing some of my old tunes on Four, it’s really thrilling for me to hear someone else interpret them.

I don’t know if these guys ever even heard those tunes before. I know Greg Tardy played “Monroe” before, but to hear what the other guys’ take on it would be hearing it for the first time, it just brings a whole new life to the song.

With anything I write, I don’t have any hard and fast idea of what it’s supposed to be. I just want it to be a way to get us into playing some music together, and I want to be surprised, and even startled sometimes. So it’s just nice to see what these guys have to say about it.

I’ve noticed that whether it’s you playing a standard or reinterpreting a tune of your own, you do this thing where you’ll leave out fragments of the melody or parts of a chord. Rather than a Joe Pass approach, where you’re putting all of the information in the tune – the basslines, the full chords, the melody – you’re picking and choosing a triad to suggest a chord or part of a line to imply a harmonic shape. It’s kind of a Monkian approach. Jim Hall did that too. Where does that come from for you?

Probably in everything I do there’s going to be some sort of Jim Hall influence in there. But also Monk. I think about Monk every day. He’s like the master of how you can stick with a melody and find infinite variety in that without leaving it, really. And that idea of leaving space: You don’t have to say everything. If the melody is really internalized in you, you begin to hear it the way Monk plays it, where you might just play a piece of the melody and internalize the rest. And it never goes away, but it becomes this springboard for all this other stuff to happen.

You have to leave room for other people to get a word in too. Like with this new album, it’s really more about four people just having a conversation

Bill Frisell

The other thing about leaving space in a song is that you want to hear what someone else has to say about it. You know, you can’t just keep pumping it out yourself. You have to leave room for other people to get a word in too. Like with this new album, it’s really more about four people just having a conversation. It’s not like there’s a real soloist anywhere. It’s more about just four people talking.

Four may be one of your least guitaristic albums, in a sense. You don’t even play on “Always,” which is a solo piano piece. And the tune “Claude Utley” is almost a drum showcase for Johnathan Blake. So the album is very conversational, and in some cases you leave the conversation entirely.

Yeah, and that’s the way it would be if you’re sitting around with some people and having a conversation. You know, you’re not talking all the time. You sit there and you check out what somebody else has to say. And then maybe you get your own thing in there at some point.

The dialoguing that you do with Greg Tardy on the Americana piece, “The Pioneers,” reminds me of the intimate duo album you did with him, More Than Enough. Maybe that one got overlooked when it came out in 2019 on the vinyl-only label, Newvelle Records, but it was a fantastic album.

Yeah, that was so great. And it is a little hard to find. Actually, the deal with Newvelle is, the masters revert back to the artist after a few years, so Greg was talking about putting it out as a CD in the near future. So probably more people might get to hear it, eventually.

It has some beautiful examples of you two playing on jazz standards, like Duke Ellington’s “Single Petal of a Rose,” Billy Strayhorn’s “Blood Count” and Thelonious Monk’s “Ask Me Now,” as well as two of your own tunes, “Monica Jane” and “Worried Woman,” the latter which you also recorded on Four.

Yeah, Greg’s been such a great musical partner. I love playing with him. He played on that History, Mystery album that I made a while back [2008]. And we’ve done a lot of gigging together over the years. He’s amazing.

Your very tender “Waltz for Hal Willner” on Four is for the late producer, who you first worked with in 1981 on his Nino Rota tribute record, Amarcord Nino Rota. He subsequently produced several albums that you played on, including Marianne Faithfull’s Strange Weather, the Disney tribute album Stay Awake, Allen Ginsberg’s The Lion for Real, David Sanborn’s Another Hand, the Charles Mingus tribute album Weird Nightmare, Laurie Anderson’s Life on a String and Lucinda Williams’ West, not to mention your own albums that he produced, Unspeakable and The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.

Yeah, Hal passed so quickly from COVID during the pandemic, within the first month or so. Such a shock there. This piece “Waltz for Hal Willner” is actually an older thing that was part of this Allen Ginsberg tribute project that I did with Hal called Kaddish [which had its world premiere in 2012 at New York City’s Park Avenue Armory and was later performed at UCLA in 2013]. It was an almost nursery rhyme kind of song that appeared in this piece we had done for Ginsberg, and somehow that melody kept coming back to me. And I kept thinking about Hal with that one.

Kaddish was the first time where he specifically said, “I don’t want you to play guitar on it, I just want you to just write the music.” And that was Hal’s way of acknowledging that I could write music. It seemed like everything I did with him would present me with some opportunity, and it was like something that I didn’t even realize that I could do myself.

But Hal would just push me through the door, and I’d have to deal with it. It was always like that with Hal. He knew more of what I was capable of than I did. You know, he trusted me like crazy, from the very first meeting with him in 1980, when no one knew who I was and he asked me to play on that Nino Rota record he produced. He didn’t know me; he just had a feeling about me.

Another song on your new album, “Lookout for Hope,” was the title of your 1987 album. You also recorded it with bassist Kermit Driscoll and drummer Joey Baron on 1991’s LIVE. Then you did it again with Victor Krauss and Jim Keltner on 1998’s Gone, Just Like a Train. It seems like a work in progress.

Yeah, originally the actual form of it was kind of complex. There was something in the form that was kind of odd and sort of awkward, so we didn’t really play it live very much back then. When I did that album with Victor Krauss and Jim Keltner, I completely dispensed with the whole counter line that was going underneath it. So I super simplified it and just opened it wide open, and that just made it easier to just play.

But then later on, I felt like I missed some of what I had originally written. So finally now, 35 years since I wrote that tune, I feel like I finally got it straight the way I wanted. It sort of solidified into this form that we’re playing on this new record. So “Lookout for Hope” was more of this struggle over all this time before I finally felt like I got it right.

It’s like “The Days of Wine and Roses.” You’ve probably played that a hundred different ways on gigs over time.

I hope so. That’s what I’ve tried to do.

You said in an interview with John Schaefer from the 2022 New York Guitar Festival, “Every note I play is like a question.” That’s a really interesting way to think about it. So in essence, you’re doing call-and-response with yourself.

Yeah, I really believe that: Every note is a question. It’s like on a micro scale and on a macro scale. If you take your instrument and just hit one note on one string, it’s like, “Okay, what are you going to do next?” But it will lead you to something else somehow.

And it’s the same thing even with a song: You learn one song and it’ll lead to something else. Like when we were just talking about “The Days of Wine and Roses,” I immediately started thinking about Henry Mancini’s other great tune, “Moon River.” It’s like they keep talking to each other somehow.

You play a phrase or play a little bit of a melody, and it’s like a conversation. Even with yourself, it’s a conversation. You play those first couple of notes on “The Days of Wine and Roses”… that’s a question. And then you answer that question, and it starts snowballing from there.

So the question could be, “The days?” And the answer could either be, “Of wine and roses,” or just, “roses.”

Yeah! Or just a blank response, like, “I don’t know.” Or think of some other completely unrelated response.

That’s what Monk did. He left out a lot of notes playing “Sweet Lorraine” or “Sweet and Lovely” or “Dinah.” When he was playing any standard, especially solo, he really was having a call-and-response with himself.

Definitely. With him, I started noticing how leaving out notes of a chord also is like a huge thing. That happened with Monk. I’m always learning from him. It’s like he’s constantly giving you a lesson or something.

A few years ago, I was playing his tune “Well You Needn’t” and I kept finding all these little details in it that I hadn’t noticed before. I’d find new things. Like I discovered that I was messing up one chord on the bridge. I was playing a Db7th chord, because that’s what everybody plays and all my schooling tells me that. And I thought, Okay, I think I’m finished now; I got everything totally together.

I finally learned this song. But then I found this Blindfold Test with Monk from Downbeat where they played him other people playing his songs. And so that chord in question – I think it was Phineas Newborn playing the song, and Monk goes, “No, no, you can’t play it that way. That chord shouldn’t have a seventh in it.”

So I was thinking it’s C, E, G, Bb, D, but he says it’s gotta be C, E, G, D. And when you leave out that one note, it sounds totally different. And that’s the opposite of what they teach you in Berklee, where it’s this thing about stacking everything up from the bottom to the top, like a pile of books or something. You just keep stacking the notes on top of each other. But if you start taking away some of the notes in the middle, all these other amazing things start happening.

Is it possible to teach a Bill Frisell methodology? Maybe the first lesson is: Leave out notes in the middle of a chord.

Yeah, with a lot of guitar books, it’s about, “How can you make this G major chord something or other sharp this, flat that, and make it into this gigantic six-note chord?” I mean, there’s so much information there. Again, I go back to Jim Hall. He played that way, where you try to pick out a couple notes within that whole rainbow of possibilities, and then it starts to set up a whole other rainbow, just with one or two notes.

Or take Monk: He’s just a master of the idea of you play the root of the chord and one or two other notes that can say so much. And that’s what makes Monk sort of almost possible on the guitar. It’s not like he’s playing all 10-fingered chords on the piano all the time, which kind of wipes out what you can do on the guitar. Instead, he makes it more accessible to where you can actually play what he played.

He played a low A, then he played a C# and a D#, and I can actually do that on the guitar. Part of that comes from just my limitations technically. If I could, maybe I would stick all the Joe Pass stuff in there too. But I can’t really do that, so I just try to make little stabs at it.

We all have to deal with our limitations. For me, I can’t actually physically play everything that I wish I could, so I’m going to just imply it or try to take a stab at something that hits close to home.

I guess the comparison would be Oscar Peterson, where he’s just blazing on the piano on every tune, filling in so much information, and Monk, where he’s leaving so much out that it’s hip. Two entirely different aesthetics on the same instrument, like you and Joe Pass.

I mean, I wish I could do that Joe Pass stuff. I remember one time I heard John McLaughlin in the mid ’70s. Now, I love John McLaughlin. He’s just a huge hero for me, right? But I went and heard him with Shakti, and I almost quit playing. I was like, I give up. It’s too much. I can’t. There’s no way I could ever do this. It was a terrible moment for me.

Then after a while, I was like, Well, fuck it! Whatever it is that I can do, I’ll just try to do it anyway. So I sort of gave up trying to play like John McLaughlin in that moment and I said, Okay, I’m going to just try to do the best I can do with whatever little bit I’ve got. And it sort of got me back playing again.

There’s quite a bit of room there between Jimmie Dodd and John McLaughlin.

[laughs] Yeah! And there are so many ways to express yourself. I mean, Robert Johnson couldn’t play like Segovia. And they’re both about as heavy music as you could possibly imagine.

That’s what’s so incredible about the guitar. When you think about it, Segovia, Robert Johnson, John McLaughlin, Jim Hall, Sonny Sharrock, Johnny Smith, Johnny Winter, Derek Bailey, Wes Montgomery and Jimi Hendrix are all playing the same instrument, tuned the same way. And it’s like, “What?!”

That Quine guitar that you recently played on tour, the blue Telecaster: Did you ever record with it?

The only time I recorded with it was on that McCoy Tyner record [2008’s Guitars]. On that record it was just a straight, normal Telecaster. But since then, I put a humbucking pickup in it. I don’t know if that’s sacrilegious, but I think Quine would be okay with it.

How many different instruments did you play on the new album?

Just two. Mainly, I played my Jay Black Telecaster. I also played a 1966 Telecaster on “Monroe,” but all the other stuff is done with that Jay Black Tele. I got it at the beginning of the pandemic, and it has these Jeff Callahan humbucker pickups in it, so it’s quiet. But they sound more like P-90s. It’s really a good guitar.

You saw Jimi Hendrix in concert, didn’t you?

Yeah! I saw him twice. The first time was in a gymnasium kind of room at a college near where I grew up. The audio of that gig [on February 14, 1968 at Regis College Fieldhouse in Denver] is actually available on YouTube.

It wasn’t the tour he did with the Monkees; it must’ve been his second tour in the States. Soft Machine was opening for him. Are You Experienced had just come out, and I didn’t know what was going on at this concert. It was just so shocking. I don’t even know if they had much of a PA; you’re just hearing the amps coming off the stage, basically. And the whole combination of the way he sang with the guitar and the massiveness of the sound... It was just too much to comprehend, for sure.

Then I saw him again the following year at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Denver [on September 1, 1968]. I think it might have been the last gig that he did with Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, and I remember there was something going on, like he was upset about something during the concert.

By that time, my parents had moved to New Jersey and I was going to school in Greeley. I came to visit them during the Christmas break and ended up going to the Fillmore East to see Blood, Sweat & Tears [on December 28, 1969]. And the amazing thing was, some unknown band from Georgia was opening that night for Blood, Sweat & Tears called the Allman Brothers Band.

This was before they had recorded anything. They came out and were like, “Oh, hi, we’re kind of nervous being in New York for the first time.” It was their Fillmore East debut and they just fuckin’ kicked ass!

This was just a few days before Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys played the New Year’s Eve concert, which became the famous live album from the Fillmore East. I remember noticing on the Fillmore marquee, it said: “Jimi Hendrix, Dec. 31,” and I’m thinking, Oh, I already saw Jimi Hendrix. I don’t need this. Man, I wish I had gone to that!

You once told me of another eye-opening guitar encounter: seeing Larry Coryell for the first time at Red Rocks.

Yeah, that was another amazing experience. He was playing a Super 400 with a DeArmond pickup, and he was getting it to feedback and everything. At one point during his solo, he walked back to his amp and just sort of rolled the volume knob on the amp with his forearm. It was so loud and wild!

Hearing Coryell and having heard Jimi Hendrix just a few months before that too… Talk about having your brain explode!

Order Four by Bill Frisell here.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.

“Gibson had lost the recipe — not only for guitar building but for making pickups based on their original design.” How Larry DiMarzio’s pickup revolution defined the sound of 1970s guitar rock

“Tariffs on products from its Mexico and China facilities would increase operating costs by $20 to $25 million.” Fender's credit rating is downgraded as tariffs pose new challenges for the guitar and gear maker