Allman Brothers Band fans of a certain age may remember Duane Betts as a teenager taking the stage to sit in with his father, Dickey, and the ABB in the mid ’90s. But 30 years later, the younger Betts has been around the block a few times, touring with his father for more than a decade, playing with California folk-rockers Dawes for a stretch, and forming the Allman Betts Band with Devon Allman. Together, they recorded two albums and toured extensively.

But while Betts’ 2018 EP, Sketches of American Music, laid down a marker for him as a solo artist, the just-released Wild & Precious Life (Royal Potato Family) is his proper solo debut.

Recorded to two-inch analog tape at Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks’ Swamp Raga Studio in Jacksonville, Florida, the album features Betts’ “dream team” – guitarist Johnny Stachela, bassist Berry Duane Oakley, keyboardist John Ginty and Tedeschi Trucks Band drummer Tyler Greenwell.

Stachela and Betts continue to expand the impressive guitar team harmony they established in the Allman Betts Band, and are accompanied by guests that include Trucks and Marcus King.

“We tracked everything live and kept whichever takes had the magic,” says Betts, who co-produced the album with Stachela and Ginty. Infused with Americana swagger, the album is a major step forward for Betts in establishing himself as a solo artist infused with, but not frozen by, his family legacy. “You write and record music and just hope it lights a fire in people’s hearts,” he says.

The first thing we hear on the album is the harmonized guitars on “Evergreen.” Was that an intentional statement?

Sort of. I just liked the song. I wrote it with a more standard opening, but my writing partner, Stoll Vaughan, was adamant about putting the harmonies on the front of the song because it was a little more unique, and once we tried it, it felt great.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The song is underpinned by a strong acoustic guitar part. Did you play that?

Yes. I played all the acoustic on a post-World War II Martin D-28, which belonged to my dad and he used a lot for writing. I know he wrote “Seven Turns” on it. I would see him playing that a lot in the early ’90s. It’s just a great-sounding guitar that is very fun to play. Some of the most fun I had was playing acoustic rhythm on “Waiting on a Song” and “Evergreen.”

What were your electrics and amps? And did you use any effects? It sounds pretty clean.

My main guitar was what I play the most onstage, the number-one prototype of my dad’s Gibson goldtop, which they made in 2001. I also played my 1961 Gibson 335 and a 1930s Gibson L-00. I used my mid-’60s Fender Deluxe Reverb and late-’50s Fender Tweed Deluxe. The only effect is a Dandrive Secret Engine fuzz pedal that J.D. Simo gifted me.

Johnny played his 2000 Gibson ’62 LP/SG Custom Shop, which he calls Stormy, my 335 and a 1960s Guild S-50 Jet Star from Derek’s collection, running through a 1960s Silvertone 1448, which is also Derek’s and a mid-’60s Fender Vibrolux Reverb.

Some of the songs recall Highway Call, your dad’s 1974 solo album, particularly the first single, “Waiting on a Song.” Was that a conscious point of reference?

I was passionately interested in having pedal steel on a few songs to capture some authentic old country-rock sounds. That music has a lot of character, with good honest, meaningful songs.

“Waiting on a Song” originally had a dreamier, big rock flow, but I gave it different treatments to see what works, and it became clear it should be an up-tempo, gliding, uplifting song. Once it took that shape, we were absolutely influenced by Highway Call and not afraid of going for that authentic gangster country vibe, which is the best. Of course, it’s not just Highway Call but Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Billy Joe Shaver…

There’s a lot of great stuff in that vein right now. Do you relate to contemporary country?

For sure, the Americana side of things. I love guys like Sturgill Simpson, Tyler Childers and Charley Crockett, and I would love to play with them and be more in that scene, which is really hip.

How did the Allman Betts albums and touring set you up to do this?

I had a lot of fun doing these records and playing all those shows. It just felt like it was time to take this next step. My time with Allman Betts gave me space to get better overall, and more comfortable as a singer onstage – which is a lot different than sitting on your bed singing to your dog with an acoustic guitar!

What’s the status of Allman Betts?

We’re on hiatus, doing other things and occasional shows, at least two this summer.

How did you end up recording at Derek and Susan’s studio?

We were hanging out at a friend’s wedding, where I was a guest and they were performing. I said I was going to make a solo album, and Susan said I should do my record at their place, so I took her up on it. It was just such a comfortable environment. They are such gracious hosts, and the property is really inspiring – on a river, with a lot of beautiful nature. And Bobby Tis, who engineered, is so gifted at what he does.

Derek and Marcus King both play great on “Stare at the Sun” and “Cold Dark World” respectively. How did that happen?

Marcus is a really talented friend, and I knew he would play amazingly on “Cold Dark World.” With Derek, it was established that he would play from the first conversation we had about me recording at their studio. That song title actually came from something he said to me: “Your dad’s a player who’s not afraid to stare directly into the sun.” It only made sense to have him on that one.

Wild & Precious Life

“Evergreen,” “Waiting on a Song,” “Under the Bali Moon” “Stare at the Sun,” “Cold Dark World”

“Under the Bali Moon” is a beautiful instrumental. What’s the significance of the title, and can you describe the writing process?

Bali is a beautiful, sacred place, where my wife and I spend time whenever money and our schedules allow. I had an instrumental idea with a lot of parts, and when we got into the studio I wasn’t sure how it was going to work out or if it was right yet. Tyler thought that the coolest part of the song came and went too fast, so he added the beat and made that part more of an emphasis. Then we incorporated all the parts that we had already written and it just came together as you hear it. It’s much more focused and has a fresher sound. He could hear the good parts and grasp what was missing.

“Colors Fade” has a very Dead feel, although the harmony playing echoes western swing and the Allman Brothers. Was that an intentional homage?

It wasn’t conscious, but as we worked up the song, it was apparent that it had a Dead vibe, and we embraced it.

You just played some shows with Phil Lesh. How was that experience?

Phil Lesh is a legend, and it’s an honor to play that music with him and the astounding cast of characters he puts together. It’s a comfortable, friendly vibe, which is good, because it’s also nerve racking – you don’t get the setlist until about 24 hours before the show, and it’s a lot to process. I would be all in to learn the stuff inside out, but there’s a lot of it and it’s not simplistic music.

Duane Betts is currently on tour. Click here for info and tickets.

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.

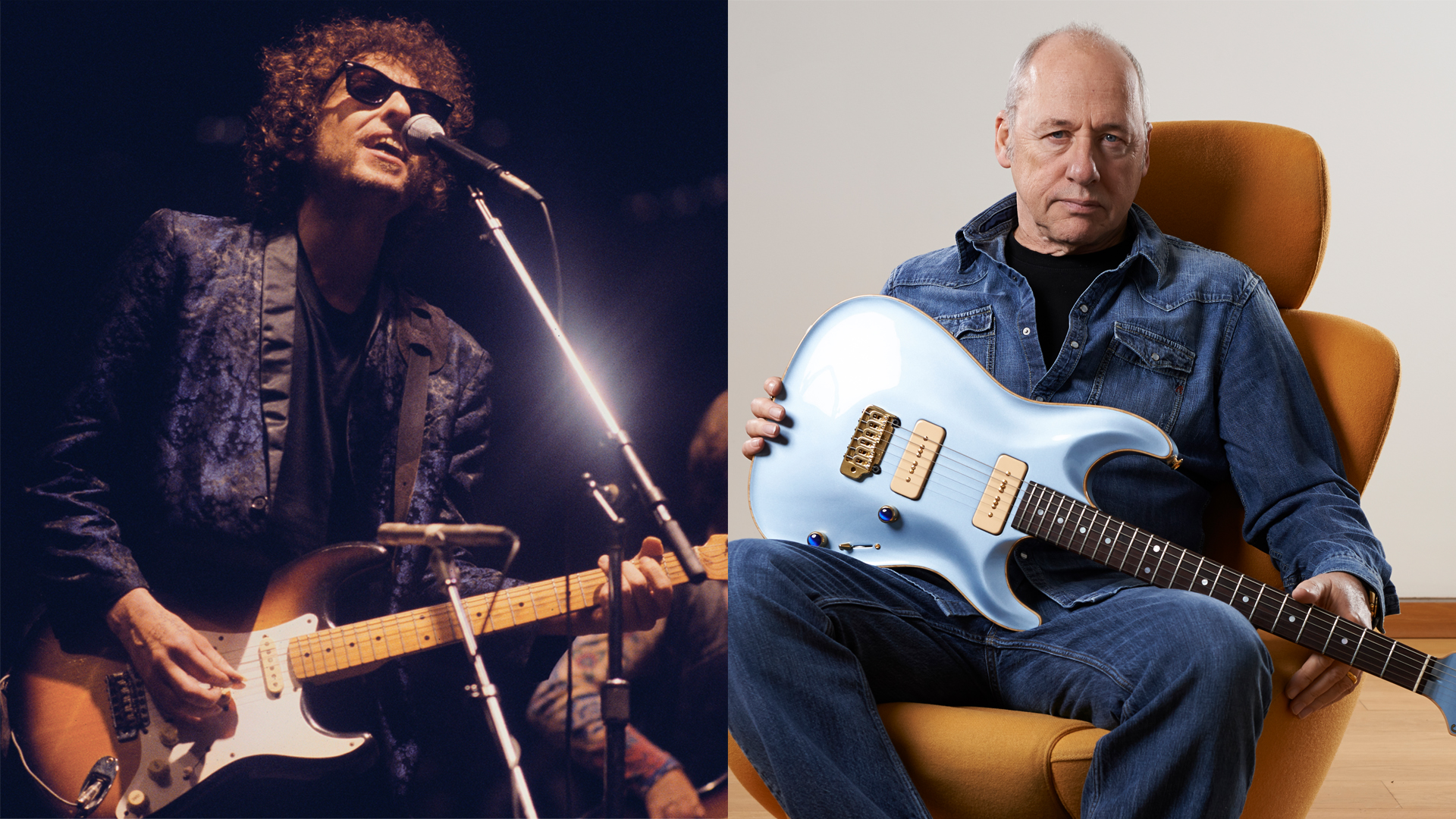

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first

“I played it for Paul Stanley when we were touring with Kiss. He had a look on his face, like 'What the hell is this!?’” Alex Lifeson tells how Rush’s early failure pushed them for their breakthrough success, 2112