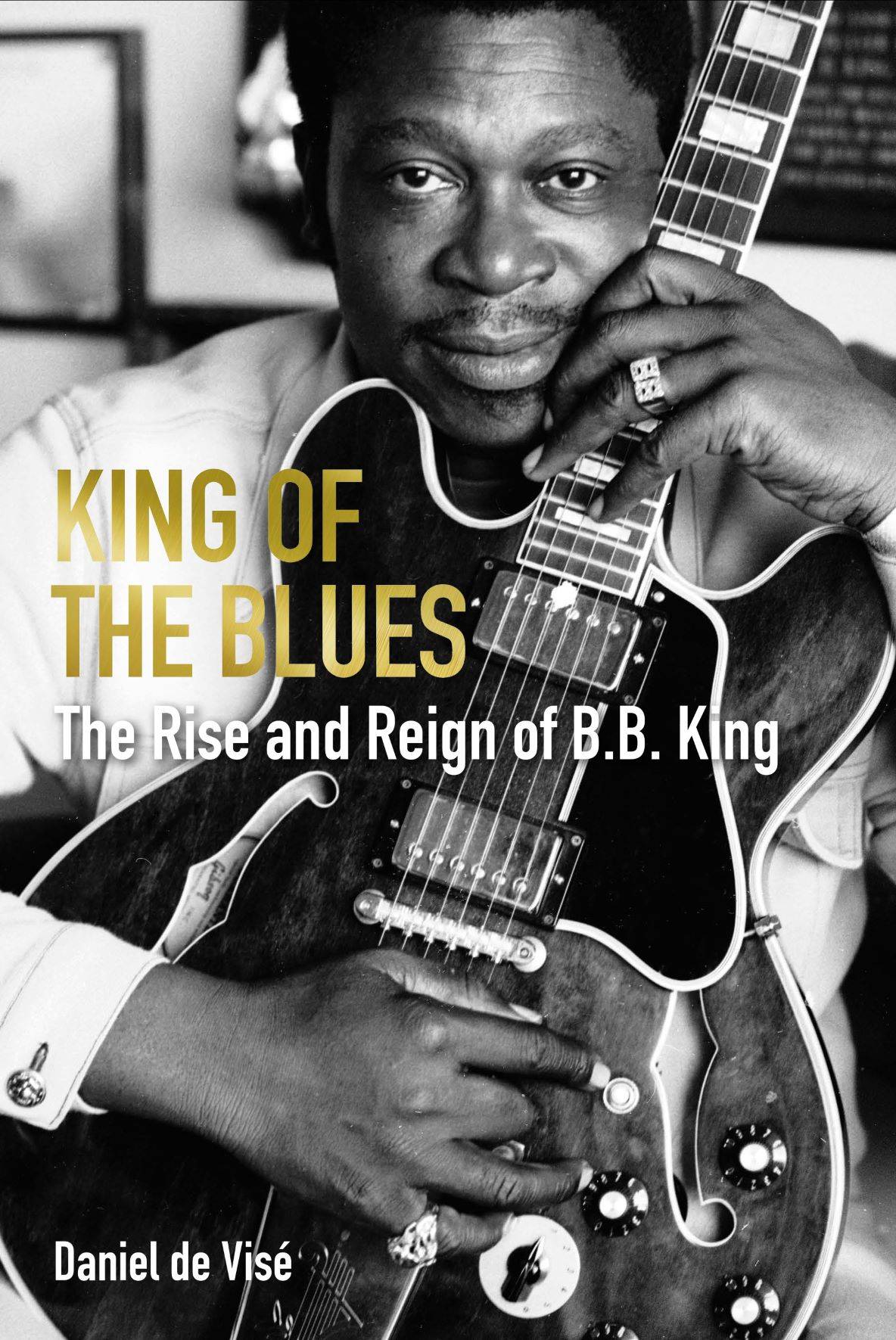

Definitive B.B. King Biography ‘King of the Blues’ Available to Pre-Order

Read this sneak peek telling the story of “3 O'Clock Blues” – the song that launched the great man’s career.

‘King of the Blues’, scheduled for release on October 5 in the United States from Atlantic Monthly Books and 14 October in Britain from Grove Press U.K., delivers the first full and authoritative biography of B.B. King, the guitarist Eric Clapton termed "the most important artist the blues has ever produced."

Daniel de Visé presents King as the archetypal guitar hero, a man whose unique, vocal style of solo guitar came to dominate popular music. The author interviewed nearly every surviving member of King's inner circle and tapped a wealth of historical sources, including crucial clippings from the Guitar Player archives.

In this fascinating and insightful excerpt from the book, de Visé tells the story of how the blues guitar legend recorded his breakthrough hit, “3 O'Clock Blues.”

One night in February or March 1951, Ike Turner was driving back to Clarksdale from a gig with his band when he came upon a mass of cars parked outside a roadhouse and a sign announcing that night’s performer as B.B. King. Turner walked into the club and found B.B. At their last meeting, Turner had sat in with B.B.’s band as a favor. Now, Turner asked B.B. if his band could play a song. B.B. agreed, and, by Turner’s account, the Kings of Rhythm “tore the house down.” At night’s end, B.B. told Turner, “Y’all got a good group. Have you ever made any recordings?” Turner, still a teenager, confessed to B.B. that he didn’t know how. B.B. replied, “I think I can set up a recording for you in Memphis with Sam Phillips.” He told Turner to show up at Sam’s studio around 10 a.m. on the next Wednesday.

B.B. turned up at the Memphis Recording Service studio shortly after Turner and his band. He pulled Phillips aside to tell the producer what he had heard at the club. At this session, Phillips was about to hear something else altogether. On the way to the studio, someone in Turner’s band had dropped a guitar amp. When the guitarist plugged in, the amp produced a horrible rasp. Everyone was deflated – except Phillips. He told the band the guitar would sound “different,” in a good way. He ran out to find brown wrapping paper to wad up inside the cabinet as a mute. Turner didn’t know quite what to make of the frenetic young producer, and he didn’t really care. “All I could picture was B.B.’s picture being tacked up on the posters,” Turner recalled. “That’s the next thing I was gonna be.”

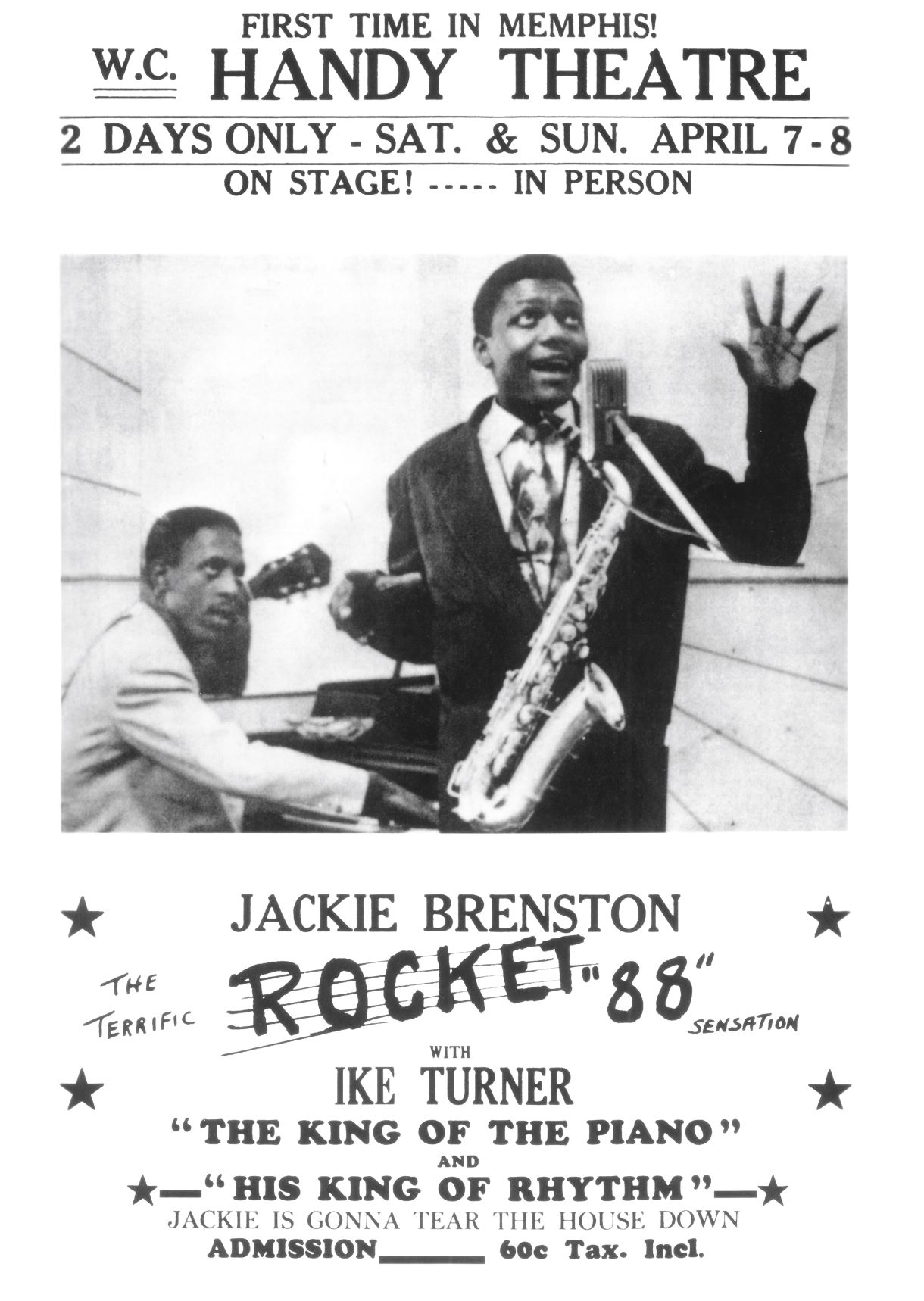

The session yielded “Rocket 88,” a song later claimed by Phillips as the first true rock ’n’ roll single. Its distinctive quality lay in the sonic interplay between the saxophone and the oddly distorted guitar, which doubled the bass part through most of the song before briefly harmonizing with the horns at the end. Just as Phillips had predicted, it sounded like nothing that had been recorded before. The song rocketed to the top of the rhythm-and-blues chart, establishing Phillips as a major producer.

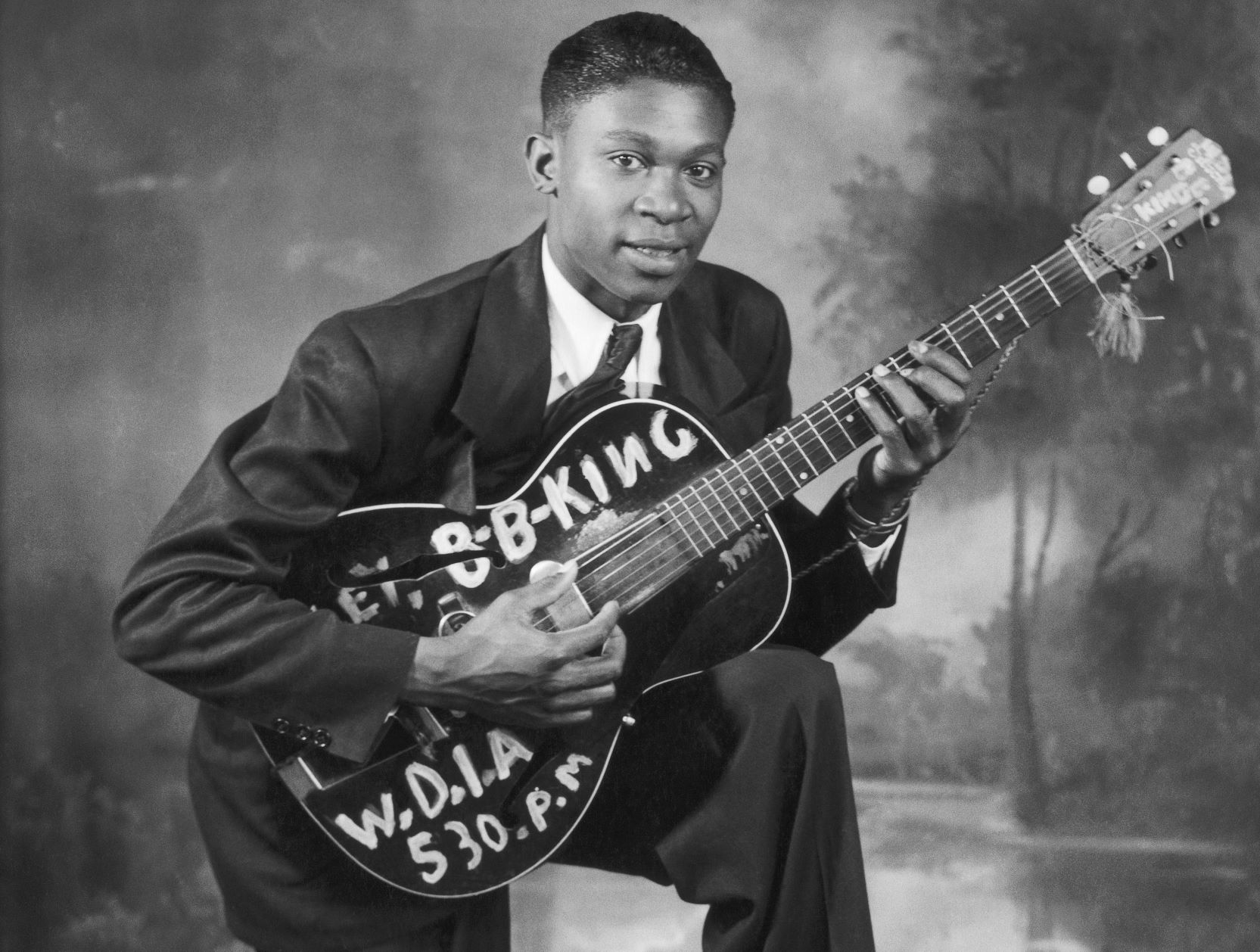

In April 1951, WDIA lost one of its stars. “Hot Rod” Hulbert decamped to radio station WITH in Baltimore. His exit left an opening for host of his three o’clock daily show, Sepia Swing Club. Bert Ferguson awarded it to B.B., who, after two years at WDIA, finally became a regular deejay with a weekly salary. The distinction is more important than it sounds. With his fifteen-minute slots singing the blues and hawking Pep-ti-kon, B.B. had enjoyed growing fame in juke joints around Memphis. But he had not been recognized, let alone embraced, by the city’s larger African American community, the rarified world of black-tie charity balls and award dinners. By the spring of 1951, B.B. ruled the roadhouses, but he had not been mentioned in any news article or column in the African American press in Memphis or anyplace else. He had not attained the civic currency of fellow deejays Nat and A. C. “Moohah” Williams, both established Memphis celebrities with newspaper columns of their own. All of that was about to change.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

B.B.’s first singles on Modern Records sold well around Memphis but failed to chart nationally. The Bihari brothers, still trolling for a hit, sent B.B. back to the Memphis Recording Service several times between the fall of 1950 and spring of 1951. The rift with Sam Phillips over B.B.’s contract quietly faded: Phillips needed their business. Affable Joe Bihari, at twenty-five the youngest of the Bihari boys, supervised a session in May 1951. B.B.’s backing band included the full Newborn family: Phineas Sr. on drums, Phineas Jr. on piano, and younger brother Calvin a new presence on second guitar, with other musicians supplying bass and horns.

The single Joe Bihari culled from this date was a cover of a rollicking boogie-woogie number by the Chicago blues guitarist Tampa Red, titled “She’s Dynamite” and chosen for its commercial promise. B.B.’s recording, like Tampa Red’s original, was prototypical rock ’n’ roll, anchored by a galloping boogie-woogie bass line, doubled on piano, and adorned with stabbing, two-string guitar bursts and tinkling piano triplets. The production hummed with overdrive. B.B. sang with abandon, capturing the sensuality of Tampa Red’s lyric. No one could fail to divine the meaning of the raucous refrain, celebrating a lover who “knows what to do” and “knows what it’s all about.” Sam Phillips harbored high hopes and dispatched the single to several deejays. But the Billboard reviewer dismissed “She’s Dynamite” as “ordinary.” The song appeared on a few local charts, but it made no mark on the national stage.

B.B.’s Modern Records singles weren’t selling well, but his career as a disc jockey stood in full flower. In October 1951, “Gatemouth” Moore departed WDIA for a new African American radio station in Birmingham. Once again, the beneficiary was B.B., who took Moore’s prized 1 p.m. slot with a new show titled Bee Bee’s Jeebies. Lucky Strike cigarettes bought time on B.B.’s shows, making him WDIA’s first African American personality with a national sponsor. B.B. made a credible Lucky Strike pitchman, being a smoker himself, even if the product he now touted was far worse for one’s health than Pep-ti-kon. In November, the radio station put B.B.’s face atop a display ad in the Tri-State Defender, a new weekly newspaper for the African American population of Memphis and environs, for its annual Goodwill Revue, a Christmastime fundraiser for the city’s Black community. B.B.’s currency was rising.

“You know, I’ve watched that boy go up the ladder, from just a 5-minute [sic] segment on Nat’s Jamboree to where he now has a series of programs all his own, and every one a hit,” wrote A. C. “Moohah” Williams, B.B.’s fellow deejay, in his column for the Tri-State Defender. “I’ve tried to figure what makes him click… and I’ve come to the conclusion… The reason B.B. is banging at the top of nearly every Hooper Rating is his all-fired sincerity.” Hooper Ratings measured a radio program’s listening audience, and the latest numbers revealed B.B. as a bona fide Memphis radio star. His close study of Arthur Godfrey had paid off.

B.B. had now cut several strong singles with Sam Phillips and the Bihari brothers. Had their collaboration continued, who knows what direction B.B.’s career might have taken. But in 1951, Sam and the Biharis fell out for good. This time, Phillips betrayed the Biharis. The brothers had the right of first refusal on everything Phillips recorded. That spring, Phillips sold the master of “Rocket 88” to a rival record maker from Chicago, Leonard Chess. The Biharis felt double-crossed.

The Chess brothers already controlled Chicago’s greatest blues-man, Muddy Waters. Now they sought to corner the market on Chicago blues, most of which was really Mississippi blues, by way of Memphis. Phillips gave the Chess brothers both “Rocket 88” and Howlin’ Wolf, who migrated north after making his name as a West Memphis deejay. Wolf’s Chess debut, “How Many More Years,” emerged in August 1951 and further redefined the Chicago sound.

Sam Phillips had no contractual power over B.B., so the rising star of Memphis blues remained in Memphis, out of the clutches of Chess. The Biharis set about finding new studio space for B.B.’s next session. They settled on the “colored” YMCA – conveniently, a block away from the rooming house where B.B. and Martha now lived. Joe Bihari rented a room at the Y for the September 1951 recording date and drove over with a Magnecord reel-to-reel tape machine in his car. He hung blankets over the windows to mask the sounds of passing cars.

Many men have claimed to have played at the Memphis Y that day: success, it is said, has many fathers. Hank Crawford, a teenager destined for jazz stardom, might or might not have played sax on B.B.’s session, possibly joined by Fred “Sweet Daddy Goodlow” Ford or Evelyn “Mama Nuts” Young or Ben Branch or Richard Sanders or Adolph “Billy” Duncan – but surely not by all of them. Bandleader Tuff Green might have handled the crucial bass part, or perhaps it was James “Shinny” Walker. Willie Mitchell, bound for fame as Al Green’s producer, might have played trumpet. Either Earl Forest, Phineas Newborn Sr., or Ted Curry manned the drums. Calvin Newborn might have provided a second guitar. If memories seem fuzzy, that is partly because Joe Bihari was recording several artists that day: the corridors of the Y hummed like a Memphis blues convention.

The song chosen for B.B.’s session was “3 O’Clock Blues,” a 1948 hit for Lowell Fulson, a West Coast blues guitarist. B.B. had the single on heavy rotation on Sepia Swing Club. Fulson rewarded the deejay by allowing him to record it. B.B. set out to put his own stamp of sincere intensity on Fulson’s song, whose lyrics “start out as an insomniac’s lament, but end up with a weepy farewell more suited to a suicide note.” It seemed perfect for B.B.’s emerging vocal style, fervent, intimate, and intense. But after the first take of “3 O’Clock Blues,” Joe Bihari recalled, “nothing was happening. It was just not working.” Joe called a fifteen-minute break. Part of the problem was the pianist, whom Joe recalled as young Phineas Newborn. Joe found his playing too jazzy: this song needed a blues beat. During the break, Joe heard someone playing the very piano part he imagined. He ran back into the recording room, shouting, “That’s what I want!” and found Ike Turner sitting at the piano. Joe hired Turner on the spot and sent Phineas Newborn home.

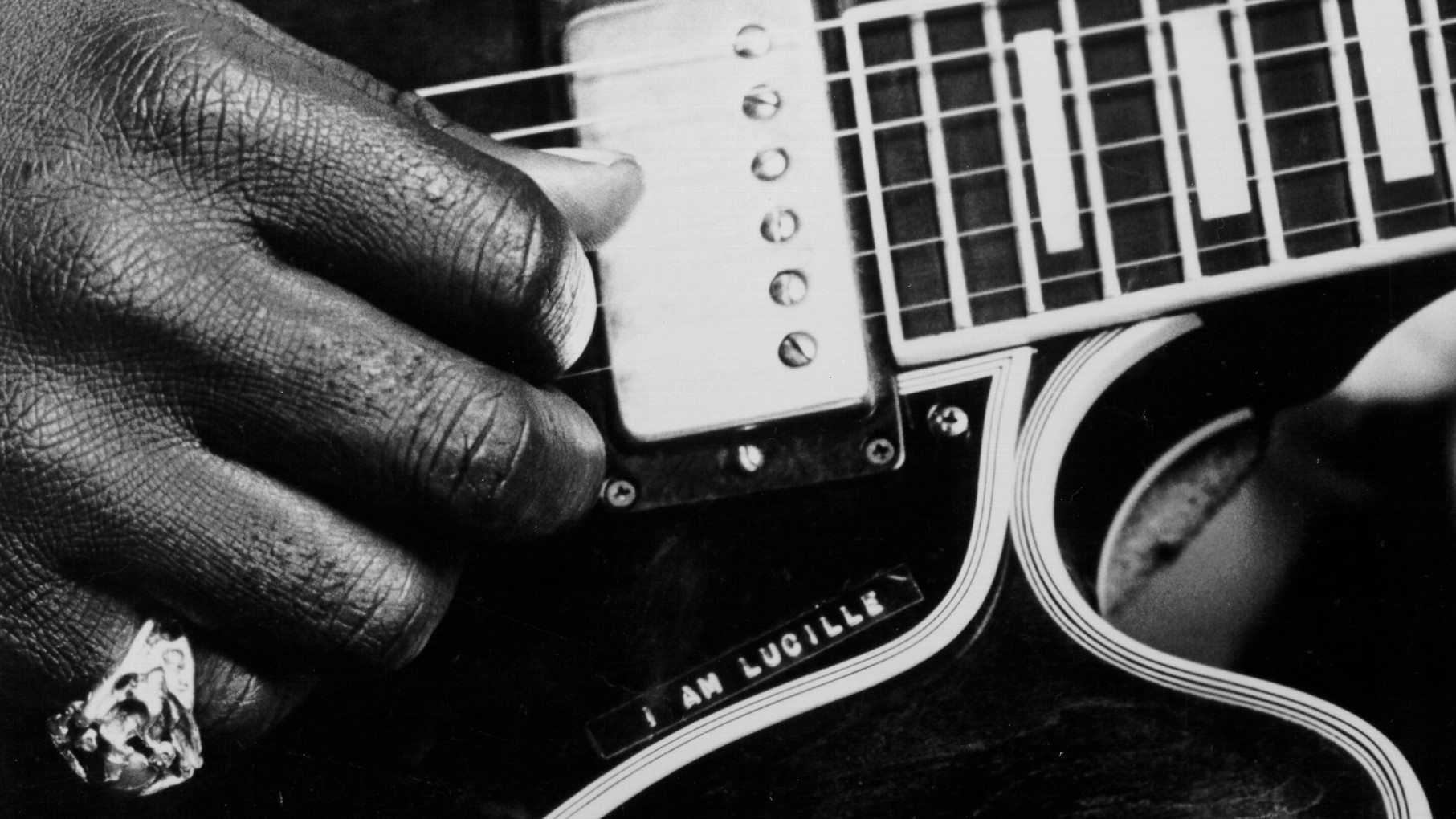

Joe tried a second take, and the song came together. “3 O’Clock Blues” was the first recording to showcase B.B. and Lucille in equal measure. It was also the first to feature both his voice and guitar high above the rest of the mix, if “mix” is the right word for a recording made on a monaural reel-to-reel tape recorder. Sam Phillips and his engineers had given plenty of space to B.B.’s voice but less to Lucille’s. No one in B.B.’s entourage had given him much credit as a guitarist. Now, at last, B.B. and Lucille stood front and center in a recording, commanding the listener’s attention. Lucille opened the song with a long, confident run of emotive notes. The horns fell into place as B.B. began to sing, marching along like a funeral procession. “Three o’clock in the morning,” he lamented, “can’t even close my eyes.” Lucille wailed a wordless reply. Ike Turner’s barroom piano tinkled in the background, combining with the dirge-like horns to weave a chilly veil of suspense.

“3 O’Clock Blues” was a triumph both for Lucille and for B.B., whose warmth and humanity finally prevailed over his native reticence on disc. Perhaps his newfound success as a deejay had loosened him up. As B.B. concluded the second verse, vowing to go down to the boilin’ ground if he couldn’t find his baby, he retreated into his speaking voice, just like Charley Patton of old, to comment on what he had just sung: “That’s where the mens hang out at.” His commentary rolled on as Lucille proceeded into an emphatic solo. He punctuated her forceful licks with cries of “Yeah!” and “Come out, baby!” The solo was simple and tasteful and masterful. Some of Lucille’s velvety phrases ended in long, sustained tones, drenched in vibrato. Others just stopped, as if B.B.’s guitar were catching her breath. B.B. erred only on the song’s final chord, which he played a half step too high. Tape was expensive, so Joe Bihari didn’t bother with another take. The rest of the performance was breathtaking. For all of Sam Phillips’s genius, the youngest Bihari brother had finally coaxed greatness from B.B. King.

“When I got back to California,” Joe recalled, “I listened to it, and I knew we had a hit record then.”

Pre-order your copy of 'King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King' by Daniel de Visé here.

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.