“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song

Absent from rock for years before the Fabs used them, dual lead lines would eventually be embraced by 1970s guitarists ranging from Brian May to Tom Scholz

"Okay, boys! Quite brisk, moderato, foxtrot!”

With that confusing but amusing musical direction, John Lennon led the Beatles into a daylong recording session that would bring to rock's forefront a musical element long absent from it: the harmonized guitar lead.

The session took place on April 26, 1966, in Abbey Road’s Studio Two, and the song was “And Your Bird Can Sing,” a composition written almost entirely by Lennon for the group’s forthcoming album, Revolver. The group had attempted the song once before, on April 20, during a session in which they recorded a complete version of the song in a jangly folk-rock style similar to the Byrds — or, closer to home, George Harrison’s own “If I Needed Someone,” from the Beatles’ previous album, 1965’s Rubber Soul.

But the April 26 remake of “And Your Bird Can Sing” would be different — a tough and jagged rocker driven by a pair of electric guitars played through overdriven amplifiers. Perhaps Lennon had a revelation that the baroque stylings of Rubber Soul were last year’s model and decided the song deserved a hard rock revision.

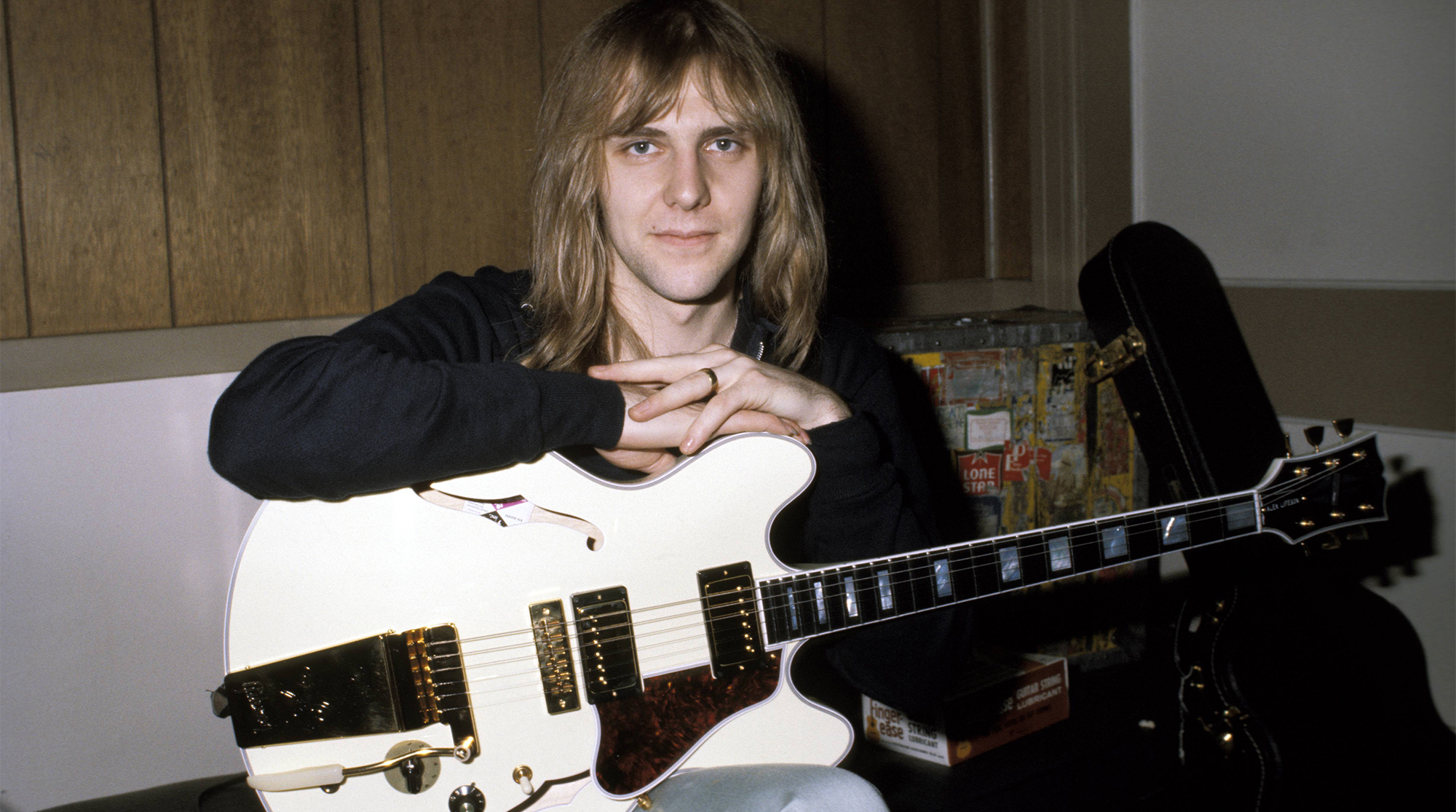

Central to that recalibration was a harmony lead-guitar line unlike anything previously heard in the Beatles’ catalog — or rock and roll. Played by Harrison and Paul McCartney on their Epiphone Casino electric guitars — through perhaps the group's newly acquired blackface Fender Showmans with 1x15 cabs — the dual guitar line gets the song off to a thrilling start, descending chromatically in waves that ripple up and down the fretboard in a swift run of tightly articulated eighth notes.

But where have we heard harmonized lead lines before in popular music, if not in rock and roll? Nearly everywhere else, it seems, including in folk, country and jazz.

Harmonized leads are a staple of folk music, usually performed on fiddle with double stops or in tandem with a second stringed instrument, such as a second violin, a guitar or banjo.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

They’re similarly a central feature in the jazz recordings of Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli, as well as in Les Paul’s earliest multitracks, where he performed each part himself or with his wife and musical partner, Mary Ford.

Harmonized lines were also a common feature of country music. Nashville musicians made ample use of harmonized leads, where they were frequently played on steel guitar, and they were likewise heard in the Bakersfield sound of players like Buck Owens, where they were usually performed on two guitars.

But for years, dual guitar leads didn’t catch on in rock and roll, where the emphasis was usually on vocals and lead guitar. Even instrumental guitar groups like the Shadows and the Ventures ignored the stylistic opportunity it offered them.

One early exception can be found in the Beatles’ own catalog: their cover of the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout,” the last song on their first album, 1963’s Please Please Me. The song’s instrumental break features Harrison and Lennon playing a riff together, with each performing different partials of the underlying chords.

There were other moments in the Beatles’ early catalog where Lennon and Harrison performed lead lines together, but in unison, such as in the solo break to Lennon’s “Nowhere Man,” from Rubber Soul.

Another honest-to-goodness harmonized lead guitar break wouldn’t appear in the Beatles’ catalog until the Revolver sessions. From McCartney’s account, the signature riff came together swiftly at the April 20 session where “And Your Bird Can Sing” was recorded for the first time.

“We wrote [the duet] at the session and learned it on the spot,” he told Bill Flanagan in 1990, “but it was thought out. George learned it, then I learned the harmony to it, then we sat and played it.”

In that initial version — performed in the key of D major — the line appeared only in the song’s solo break and outro, played by Harrison and McCartney on their Casinos. Elsewhere in their recording, Harrison plays his Rickenbacker 360/12 electric 12-string.

The line would play a more central role in the April 26 remake, where the song’s key was moved up a whole step, to E major, and the rhythm was given a harder rock beat. The group liked take 5 enough to treat it to vocal and guitar overdubs. As the session tapes reveal, the harmonized line was still played in the mid-song break and outro, but Harrison and McCartney added yet another dual-guitar element for the song's middle-eight breaks ("When your prized possessions start to bring you down...").

It took five more takes before the Beatles hit on the magic formula. Take 10, the one heard on Revolver, finds the passage — its first half — played in the intro, as well as in the middle and outro, where Harrison and McCartney finish by repeating the first measure twice before the recording concludes with the final note from take 6, in which McCartney’s staccato bass notes flutter up an octave.

In addition to the line they created for the middle eight, the guitarists play a fragment of the dual-guitar line in the breaks between the first two verses, as if eager to fill every available space with this unique — for 1960s rock — element

The result is a hard rock track that sounds as potent today as it did upon its release. Producer Rick Rubin was clearly moved by its power when he interviewed Paul McCartney for McCartney 3, 2, 1 , his 2021 miniseries exploring the artist's catalog of work.

“To me, it has a Celtic flavor,” Rubin says after playing the recording for McCartney, as if fumbling to understand what he’s hearing. “I don’t know why that is.”

“Well, you know... I mean, we’re Liverpool boys,” McCartney explains. “And they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland. So it’s likely that there’s all those influences, you know.

“But we would just make up the solo, in this case, and just learn the harmony and the solo and then play the two live.”

The two also reflect on the effect that those charging harmonized guitars have on the listener.

“That’s the thing,” McCartney says, “you can hear the excitement of us just making stuff up, can’t you.”

“It sounds thrilling,” Rubin says, adding, “the energy is contagious.”

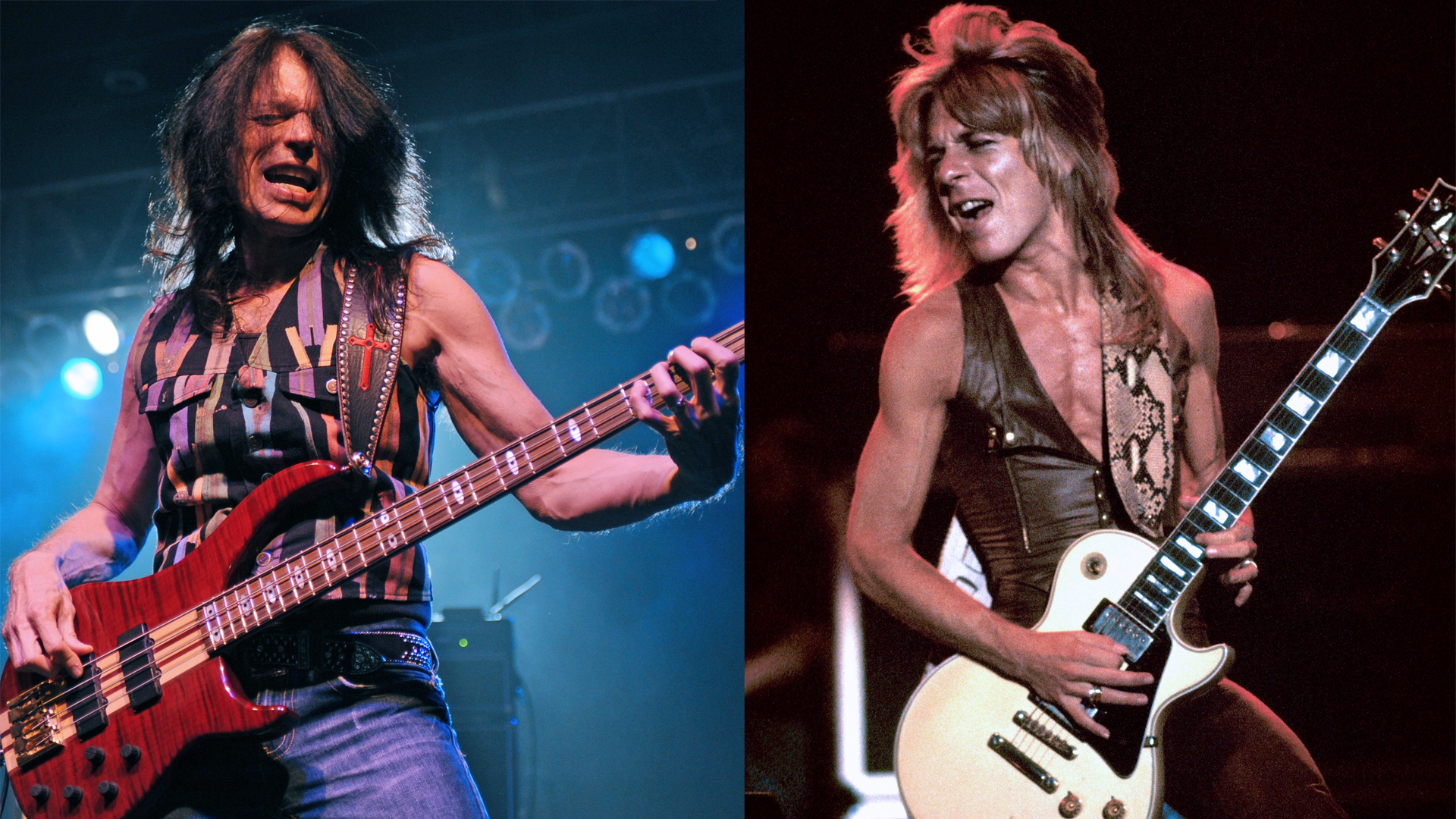

Indeed it is, and it certainly was to other groups. By the 1970s, harmonized guitar lines were everywhere in rock, employed by Todd Rundgren, Queen’s Brian May, Boston’s Tom Scholz, Eagles’ Don Felder and Joe Walsh, and Wishbone Ash’s Andy Powell and Ted Turner, to name a few. And, no surprise, Irish rockers Thin Lizzy made dual-guitar lead lines a central element of their sound.

The Allman Brothers would go on to popularize harmonized guitars in tunes like Dickey Betts’ “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” "Ramblin' Man" and “Jessica,” although Betts was more obviously influenced by his own country leanings and love of Django Reinhardt, rather than the Beatles. The Allman Brothers would, in turn, inspire countless southern rockers to incorporate harmonized guitar lines, making it a ubiquitous guitar element of 1970s rock and roll.

But as usual, it was the Beatles who got there first.

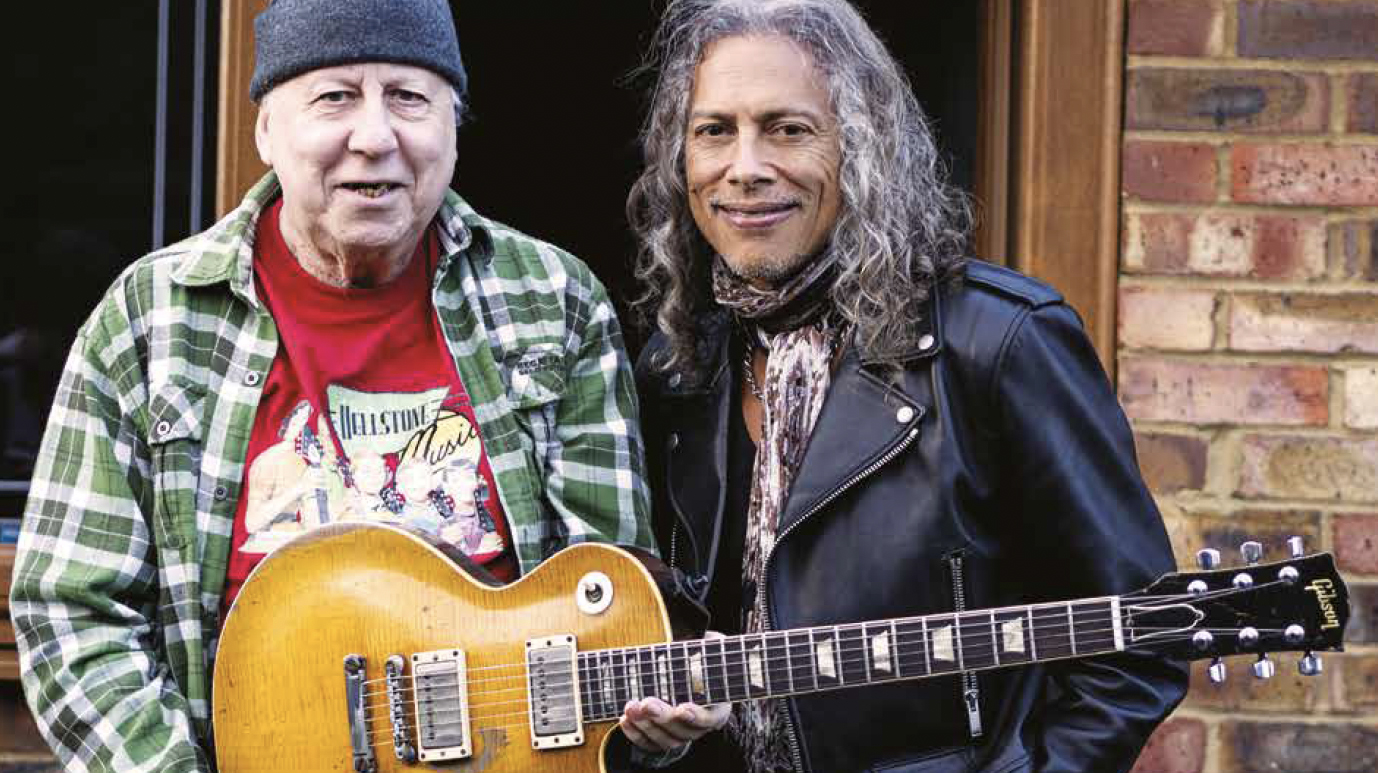

"When they left town, I went to the airport and got to meet Ritchie, and he thanked me for covering for him." Christopher Cross recalls filling in for a sick Ritchie Blackmore on Deep Purple's first-ever show in the U.S.

"It’s as if all of Jeff Beck’s genius is right here on one album. There’s a taste of everything.” Joe Perry riffs on Beck, the Yardbirds and "The 10 Records That Changed My Life"