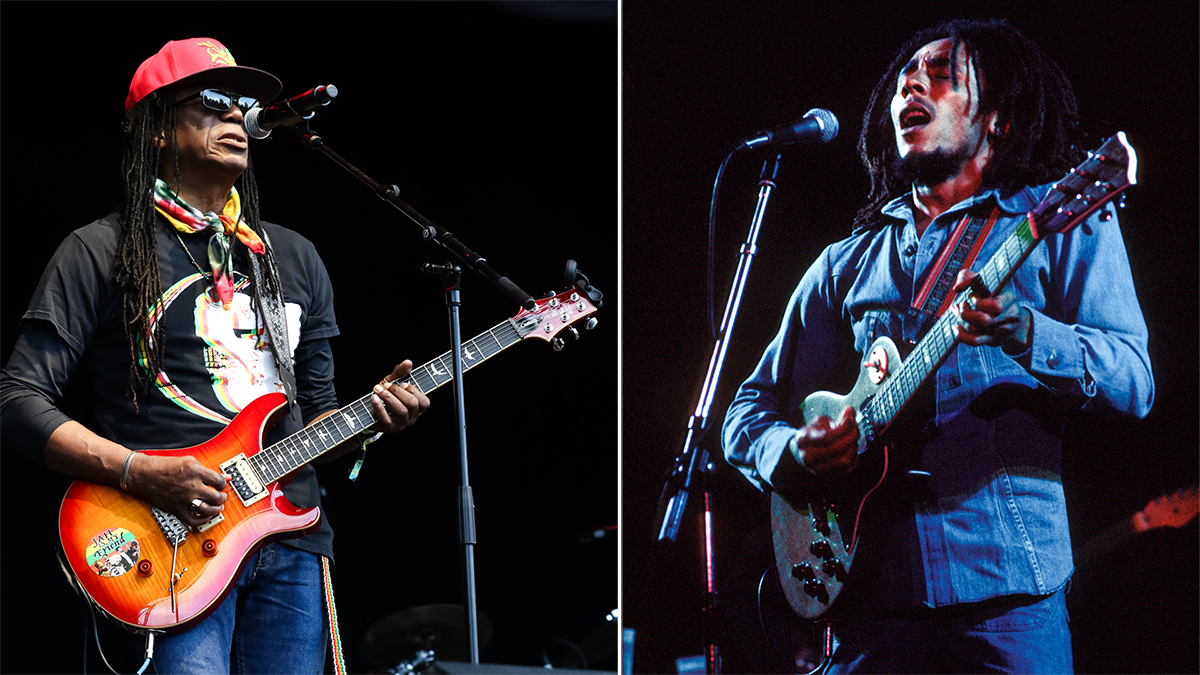

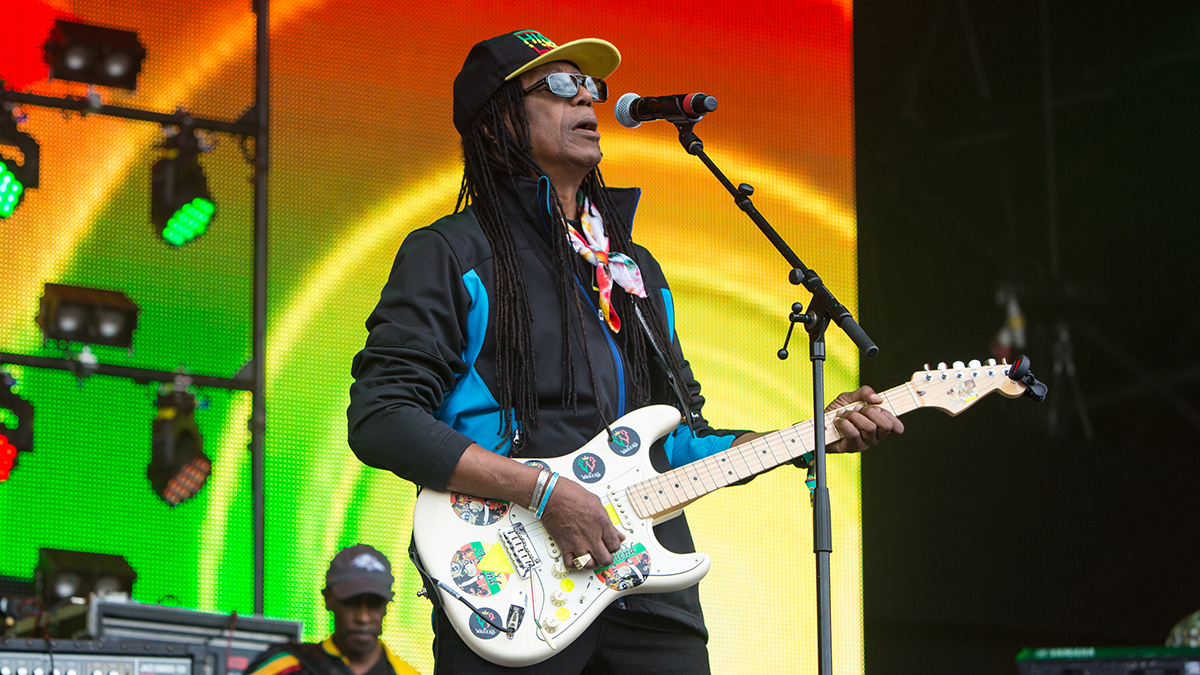

“Bob heard I was the ‘young Hendrix of London.’ He said, ‘How did you do that!?’ " Junior Marvin on being picked by Bob Marley as his lead guitarist on 'Exodus,' the album that brought reggae to the world

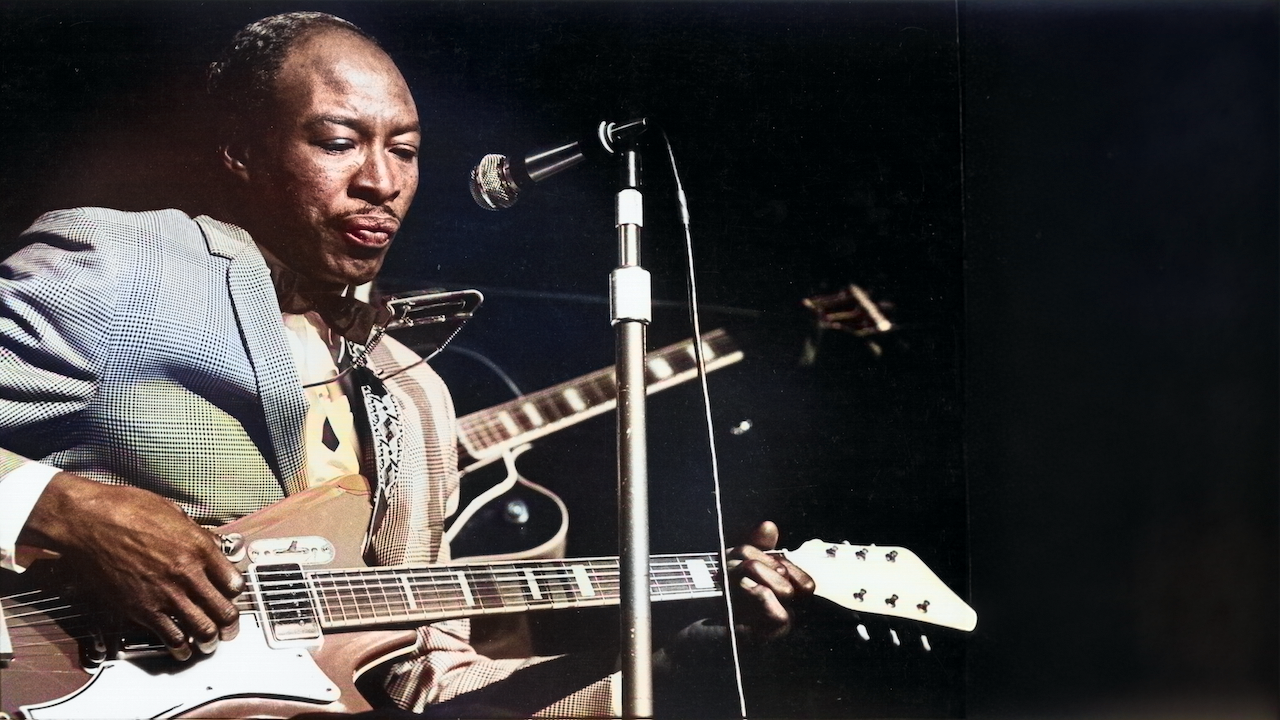

Marvin says engineer Roger Mayer brought him a Strat from Manny’s in New York specifically chosen for album sessions

Given the chance to reflect on Exodus, Bob Marley and the Wailers 1977 magnum opus, Time Magazine's Album of the Century, and quite literally, the most popular reggae album of all-time, Junior Marvin, who played lead guitar on the record, smiles saying: "I find myself very fortunate."

Fortunate, indeed. Marvin was new to the Wailers camp at the onset of the Exodus sessions, but he was far from an unknown entity. Marley had tagged him as Al Anderson's replacement for a reason. In fact, at the time of Marley's proposition, Marvin was mulling an offer from Stevie Wonder to join his band, an deal that Marvin carefully rebuffed before signing up to be the Wailer's new blues-rock-leaning six-string star.

Prior to joining the Wailers, Marvin had worked with everyone from T-Bone Walker to Steve Winwood to Keith Hartley. But it was his affinity — and comparisons — to Jimi Hendrix that drew Marley to Marvin like a moth to a flame. Marvin's eclecticism would serve him well, as the era of stylistically unique, technically proficient electric guitar players was dawning.

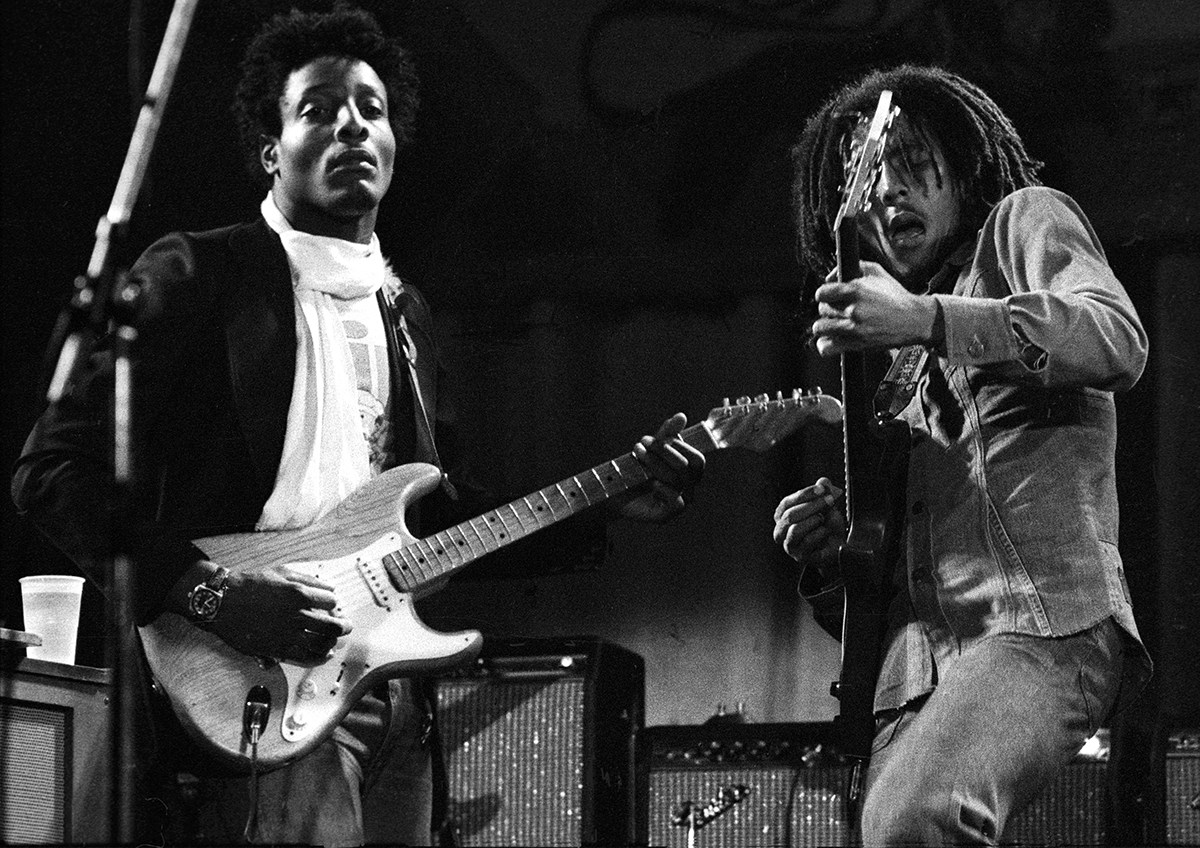

The mood was upbeat as Marley and the Wailers entered Island Studios in London, in early 1977, to record the album that would become Exodus. Just the year before, Marley had survived an assassination attempt, and he was eager to come back stronger than ever.

"I think Bob was happy to be alive," Marvin says. "The attempt on his life and surviving that made him very positive.

"It was like he got another chance to make a mark. It was a chance to say something that everyone could learn from. For Bob, it was like, 'Okay, let's not keep fighting and killing each other. Let's get together and play.’ It was a spiritual influence and a chance to do something with his life — and for others."

But it wasn't all fun and games. "The energy was good," Marvin says. "But it was work. Bob was a real workaholic at the time. He was just on it."

The effort paid off. Exodus was like a shot heard around the world, hitting across multiple charts in multiple countries and spawning iconic songs like "Jamming," "Three Little Birds," "Waiting in Vain," "Natural Mystic" and "One Love/People Get Ready."

In the years since its 1977 release, Exodus has been cited as not just a touchstone of reggae music and a cornerstone of Marley's catalog — and popular music — but a feather in the cap of all involved, especially Junior Marvin.

"It was more of a life thing, rather than just being a guitar player," Marvin says of his time with Marley. "People love what the Wailers accomplished as musicians. It’s unique, organic, original, and inspirational. People talk about the guitar lines, the blues, the jazz, and the rock influence all blended into one and how it affected their favorite songs. It's very emotional and uplifting to have that response as a musician and entertainer."

Given that you'd just replaced Al Anderson and were quickly thrown into the fray, did you feel pressure to establish yourself as something different from Al or Peter Tosh before him?

No, it wasn't competitive in that way. Al definitely has a sound that is different from my sound, but there was no animosity or jealousy. Everybody respected each other's talent, which made things blend together rather than compete. It was productive. And any criticism from Bob was constructive, and he was a positive guy and a hard worker. It was special.

Having said that, as you entered the studio to record Exodus, what was your outlook and approach to the guitars?

First of all, there was a very famous area called Portobello Road in London, which was close to the Island Records studio. I lived in that area, and the studio was around the corner, so I got involved in recording techniques, how to transfer sound, and get the most out of it with microphones, amplifiers and soundproofing.

All those things that were important back then in terms of recording organically, analog, and getting sound rather than noise — and being in tune. That was when I met Roger Mayer. He helped us make sure the instruments were tuned properly, and the response from the instruments was proper. When we played together, it sounded like everybody was at the same pitch, you know? So that had a big impact on things.

And that was a significant change from how the Wailers had done business in the past, right?

I mean… living in the West Indies, most of the musicians and their instruments got really burnt out in the sun and the humidity, so they don't sound the same anymore, or, at least, not as good as they could, you know? So, meeting and working with Roger brought some technical aspects to sounding good.

Also, having a good studio, like the one Island Records had at the time in London, that was up with the latest technology and available 24 hours a day helped. We could go in at any time we wanted and just continue to work. It was a great experience and opportunity. We just tried to make the most of it; I think we did.

Did Bob give you a specific direction on how he wanted you to approach the guitars, especially since your style was much different from Al's?

Bob said that he was a big, super Jimi Hendrix fan. He heard that I was the "young Hendrix of London” and pretty much said, "How did you do that?" [laughs] I guess… growing up in London and in New York in America, I had a different approach. I got to meet people, hang out with a band called Traffic and tour with T-Bone Walker. I was just in the mix of all of it.

What gear did you bring into the studio with you at the start of the Exodus sessions, and how did Roger Mayer help you dial it in?

When I went in, it was February or March of 1977. That was when we were working with Roger. Roger actually went to Manny's Music store in Manhattan, New York, and picked out a Fender Stratocaster for me out of about 40 or 50 that were there in the shop.

He brought it over to the studio in the U.K.?

Yes, he had brought it over to England via courier. It was the first guitar I'd had that was no shit. [laughs] That helped a lot, you know? Then he worked on Aston Barrett's bass; even before that, he'd worked with Al on his guitars. Roger was just great to have there and to have that experience working behind us.

Tell us about putting together "Jamming."

“Jamming in the name of the Lord.” That was a classic song. I wish I'd written that song. [laughs] I had some good ideas for songs, but Bob brought them to life, you know? But "Jamming" was one of those songs that we all enjoyed playing.

It's like the song says, "Jamming in the name of the Lord, you're jamming all day." It was just fun and not planned. It was organic — and that's what jamming is really all about. You have a basic idea, you work around that idea, and put things into that idea musically and lyrically… it was one of those kinds of songs.

What was the process of recording your guitar parts for "Three Little Birds" like?

It kind of reminded me of the beach and being in Jamaica. The guitars kind of sound like something the famous California band The Beach Boys would do, you know? It was that kind of thing, and those were the kinds of ideas that I put in on that guitar.

That's an interesting take. How so?

It became what you might say is a New Orleans, Meters type of funk, with a bit of Motown, a bit of Stax, and all those labels from way back that made R&B music, along with the Beach Boys. And the Meters, at the time, had a big influence on Jamaican music's rhythm and melodies. So there were a lot of guitar sounds going all over the place, but I think we got some nice ones with "Three Little Birds."

How about the title track, "Exodus?"

"Exodus" was, by chance, like a freedom shot. It just moves like a train and chugs along. And every so often, the horns would come in, and then the keyboard part would come in. But the guitars had one basic kind of riff. It's like blues, in a way, but without all the changes.

It's basically one chord and having an arrangement that would bring the horns and vocals in. Then, certain little guitar lines come in; it's a good dancing song. A lot of clubs and DJs play that record all over the place, all over the world.

What would you call out as the key to your guitar tone on the Exodus record?

The way I looked at it, it was kind of like a gospel sound and feel, you know? It had that kind of church vibe and just liked to swing along for everybody to sing. Like, [quoting from “One Love”] “Praise to the Lord, and feel all right, let's get together and feel all right." The sound was inviting you to come along and sing it; that was spiritual to me.

How would you say you most impacted Exodus on guitar?

They call me the rock and roller, you know? [laughs] I'm the blues man and the rock and roller. Little Richard, Howlin' Wolf, T-Bone Walker, B.B. King, Albert King, Buddy Guy, Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan — I added that sort of vibe there. And being a big Hendrix fan, it was like, "Bob loves him some Hendrix," so I was right on time.

To that end, it's not a coincidence that Bob's sound shifted when you entered the band, and he delivered the biggest album of his career—and perhaps the reggae genre.

And I'm very proud of it, too. Having the experience of working in the studio and learning mixing and recording techniques, I became more than just a guitar player; I became a co-producer. And that album, Exodus, was voted the Album of the Century by Time magazine. I'm just so honored. I'm very proud of it. It's been a blessing for me, and it's a blessing for it to be shared with the whole world.

Would you say Exodus the greatest reggae guitar album of all time?

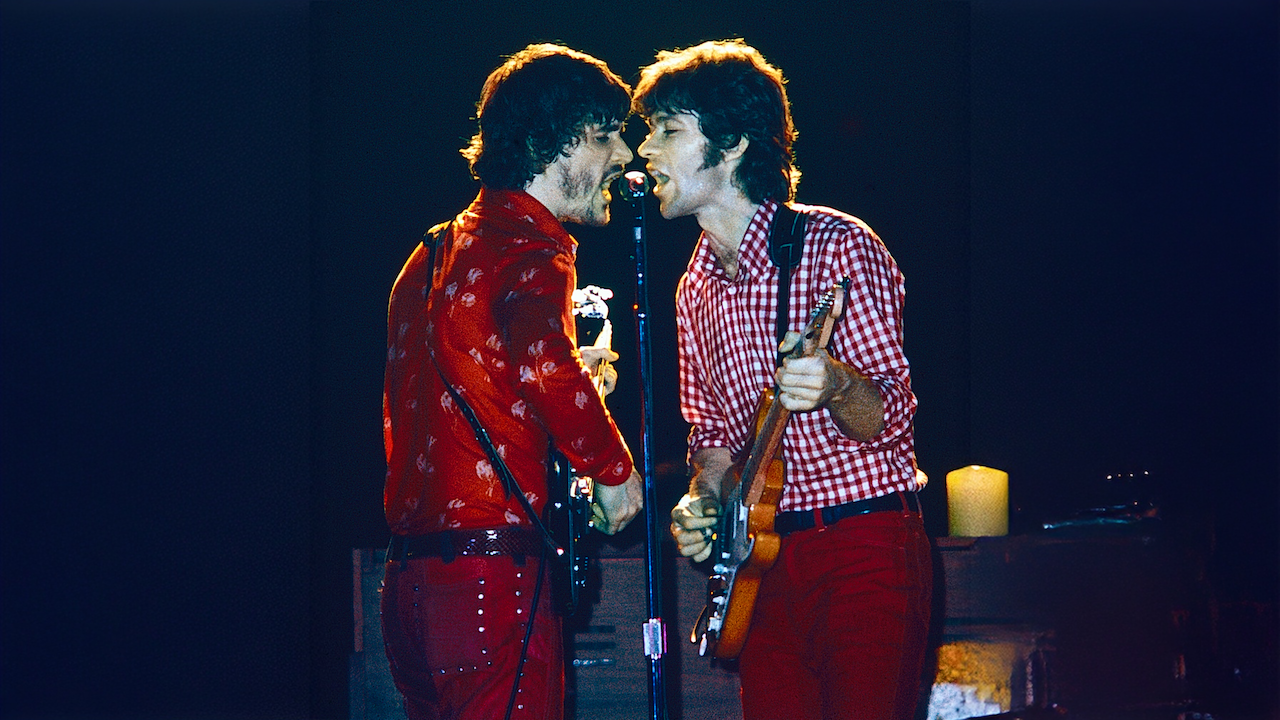

I might be a little biased about that question. [laughs] I think it's one of my best accomplishments as a guitar player. I think it's one of the best band recordings ever. We certainly proved it by being voted the Album of the Century by Time Magazine. We were up against Michael Jackson, Elvis, Miles David, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, the Beatles and the Jackson 5. And Exodus came out on top. I'm very proud of that.

But as a guitar album, with Roger Mayer having worked with Jimi Hendrix, Ernie Isley, and people like that, I got the opportunity to get the most out of that and all he had done in the past, along with what he was doing now with us. We became really good friends. It wasn't just him working for us; it was more of us putting our minds together and coming up with sounds that really made an impact.

It's still making an impact throughout time, and throughout all the decades, you know. So Exodus is something that we all can be very proud of. I'm happy that we shared it with the rest of the world and that we got the chance to add to music history.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“What he's playing is often very simple. That's the beautiful thing about David.” Steven Wilson on David Gilmour and remixing the newly released ‘Pink Floyd at Pompeii — MCMLXXII’

“I did the least commercial thing I could think of.” Ian Anderson explains how an old Dave Brubeck jazz tune inspired him to write Jethro Tull’s biggest hit