“I really don't like it. I think there's something wrong with it.” Eric Clapton hated Cream’s “Crossroads." But is there an even longer version of it?

Producer Tom Dowd said Cream never played “Crossroads” for less than seven minutes in concert and was certain the 'Wheels of Fire' recording was an edit

“I thought of Cream as sort of a jazz band,” bassist Jack Bruce once said, “only we never told Eric he was really Ornette Coleman! Kept quiet about that.”

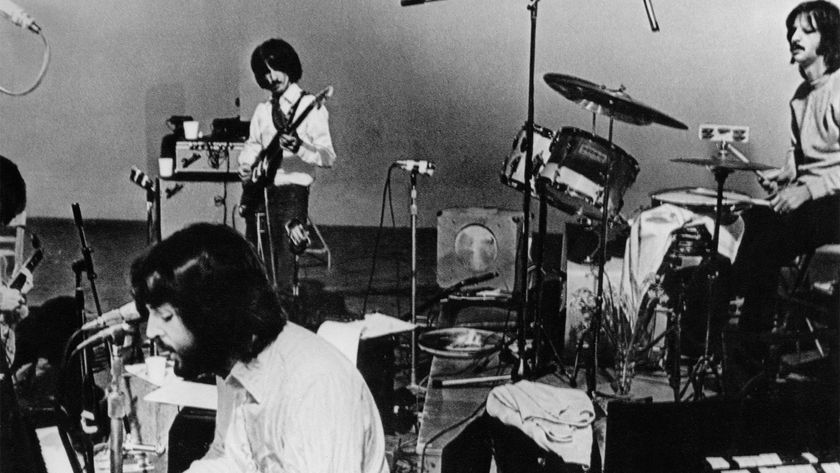

Like a jazz band, Cream made spirited, virtuoso improvisation a key part of their approach in concert. Together, Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker introduced jamming to rock audiences, first in concert and later on albums like Wheels of Fire, Goodbye and, following their breakup in 1968, concert discs like Live Cream and Live Cream Volume II.

Some of the longest jams in their catalog include Wheels of Fire’s “Spoonful” (16:47) and “Toad” (16:16), Goodbye’s “I’m So Glad” (9:13), Live Cream’s “N.S.U.” (10:13) and “Sweet Wine” (15:15), and Live Cream Volume II’s “Steppin’ Out” (13:38).

And then there’s “Crossroads,” certainly the best known of the trio’s live jams. The song appeared on the second disc of 1968’s double-LP Wheels of Fire, along with other live recordings from Cream’s March 7–10 concerts at San Francisco’s Fillmore and Winterland venues that same year. Recorded at Winterland on March 10, 1968, “Crossroads” comes in at a tidy 4 minutes and 18 seconds, making it one of the shorter live cuts in Cream’s catalog.

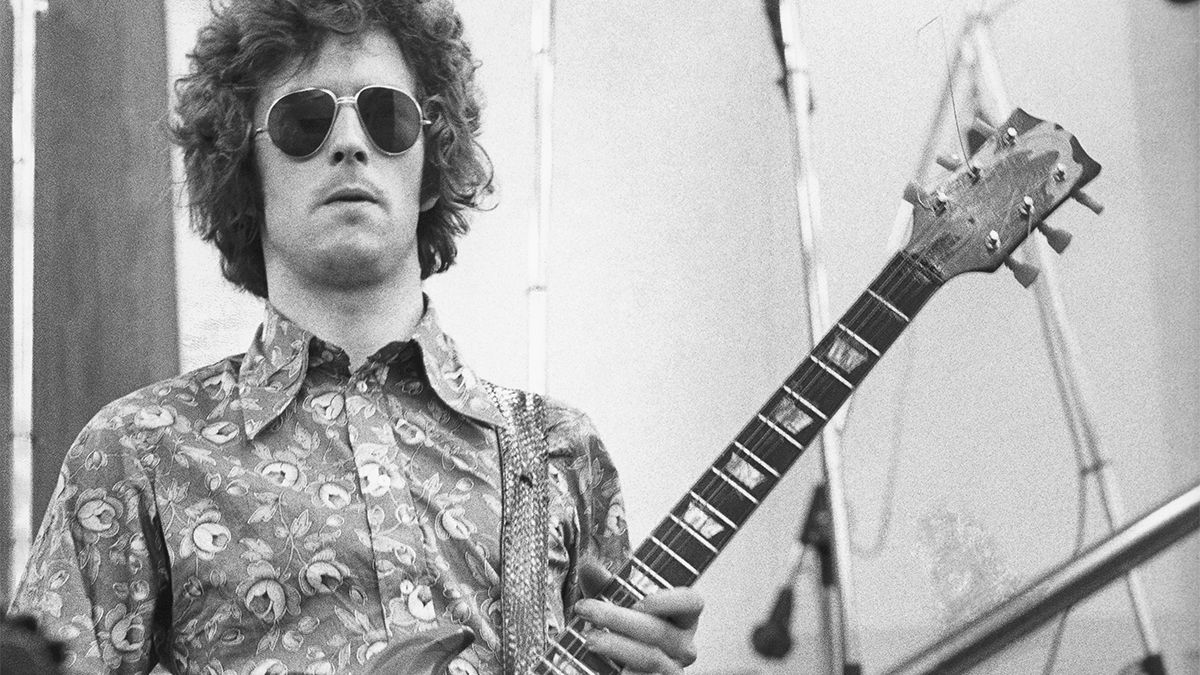

For fans of Eric Clapton’s electric guitar soloing, there is perhaps no better example of his guitar prowess. Over six verses, Clapton plays some of the most lyrical and impassioned guitar in blues rock — not just guitar wankery but lines that build and develop into statements you can recall in an instant and even sing. No less a Clapton fan than Eddie Van Halen learned the “Crossroads” solos note for note. That's how important they are.

So wouldn’t it be great if there was actually a longer version of this celebrated recording?

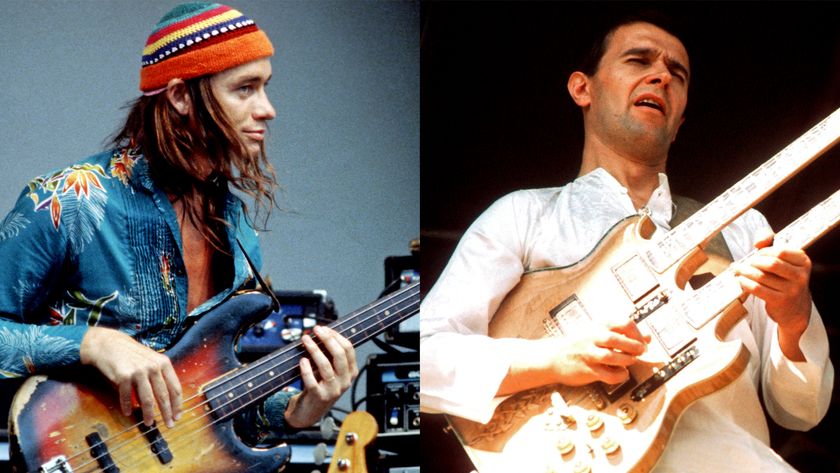

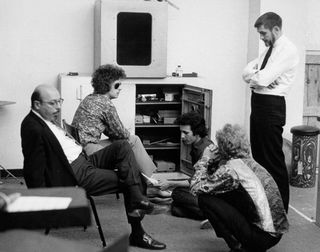

If the late producer Tom Dowd is to be believed, there is. Over his long career as an engineer and producer, Dowd recorded Clapton in Cream, solo and in Derek and the Dominos, which is why he was chosen to reminisce about the guitarist and his recordings for Guitar Player’s July 1985 Eric Clapton issue. In doing so, he made an admission that was tantalizing to Clapton fans.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“On the Wheels of Fire album, in the live portion, a lot of things were ultimately brought down to shorter versions than were played onstage,” Dowd said. “We did two recordings in San Francisco in three days' time — one at Winterland and the other at the Fillmore.

" 'Crossroads' onstage, for instance, was never under seven to 10 minutes long. So the solos between the vocals were edited. But there was no overdubbing whatsoever on any of the live albums.”

Definitive as it may sound, Dowd’s declaration has a few problems. For one thing, nearly 60 years on, no “unedited” recordings of the Winterland "Crossroads" have surfaced. In addition, other live cuts of "Crossroads” from the group's autumn 1968 farewell tour are arranged like the Wheels of Fire track, right down to Bruce's "Eric Clapton" acknowledgement at the song's end. The group’s L.A Forum and San Diego Sports Arena performances in October 1968 both clock in at around four minutes and change, while Cream’s November 26, 1968 presentation at the Royal Albert Hall runs the same length as the Wheels of Fire version.

If anything gives support to Dowd’s memory of the recording it’s the moment at 2:44 where Clapton seemingly gets ahead of the beat and the players lose the “one” for a couple of measures. Did the group make a masterful save and recover before going completely off the rails? Or is this a less-than-ideal edit made to trim the song down to a more reasonable length?

Eric Clapton seems to think it was the former. The guitarist, who was interviewed by Dan Forte in that same issue as Dowd, couldn’t say if the producer was right, but he acknowledged that the group often came close to completely losing it when jamming.

GUITAR PLAYER "Cream's live version of 'Crossroads' is often cited as one of the best live cuts and live guitar solos ever recorded. Was that edited from a longer jam?"

ERIC CLAPTON "I can't remember. I haven't heard that in so long — and I really don't like it, actually. I think there's something wrong with it. I wouldn't be at all surprised if we weren't lost at that point in the song, because that used to happen a lot. I'd forget where the 1 was, and I'd be playing the 1 on the 4, or the 1 on the 2 — that used to happen a lot. Somehow or another, it would make this crazy new hybrid thing, which I never liked, because it's not what it was supposed to be.

"What I'm saying is, if I hear the solo and think, God, I'm on the 2 and I should be on the 1, then I can never really enjoy it. And I think that's what happened with 'Crossroads.' It is interesting, and everyone can pat themselves on the back that we all got out of it at the same time. But it rankles me a little bit."

What’s curious is that even Clapton isn’t sure if the song was edited down — and he performed it.

But perhaps there are aspects to this we don’t know. Let’s say Dowd was right and “Crossroads” was originally much longer. Imagine Cream, out on their farewell tour in autumn 1968, decided to perform the song in its abbreviated Wheels of Fire format for one reason or another — maybe they preferred it, or figured it would let them wrap up the show faster and get out of each other’s hair. By the time of this interview, even Clapton could be excused if he'd forgotten such minor details.

Instead, what he recalled was his reaction — it rankled him. All guitarists would be blessed to feel so rankled. But then Clapton never did fully enjoy his role in Cream, where he was something of the odd man out. As Jack Bruce explained in a 2012 interview with Guitarist, Clapton thought Cream would be a blues trio and give him a chance to be like his idol, Buddy Guy. Meanwhile, Bruce and Baker were jazzheads hellbent on infusing the group’s blues-rock with freeform improvisation.

The results speak for themselves. As for "Crossroads," at any length it serves up some of the greatest guitar playing in rock and roll history.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

"I was like, ‘How does he do that?’ Jimmy Page told me, ‘He works at it. He just works at it.’” Joe Perry on Jeff Beck, the Yardbirds and "The 10 Records That Changed My Life"

"Shredding is like talking a foreign language at 10 times the speed of sound. You can't remember anything." Don Felder reveals the unlikely influence behind his iconic guitar solo for the Eagles' “One of These Nights”