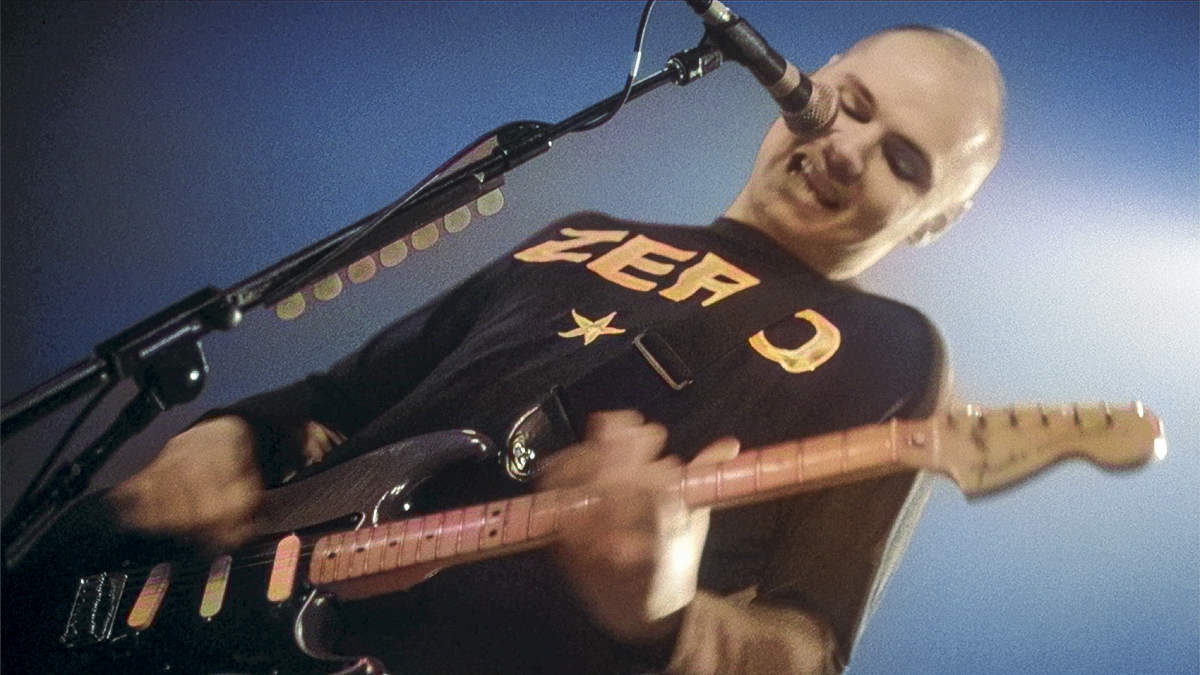

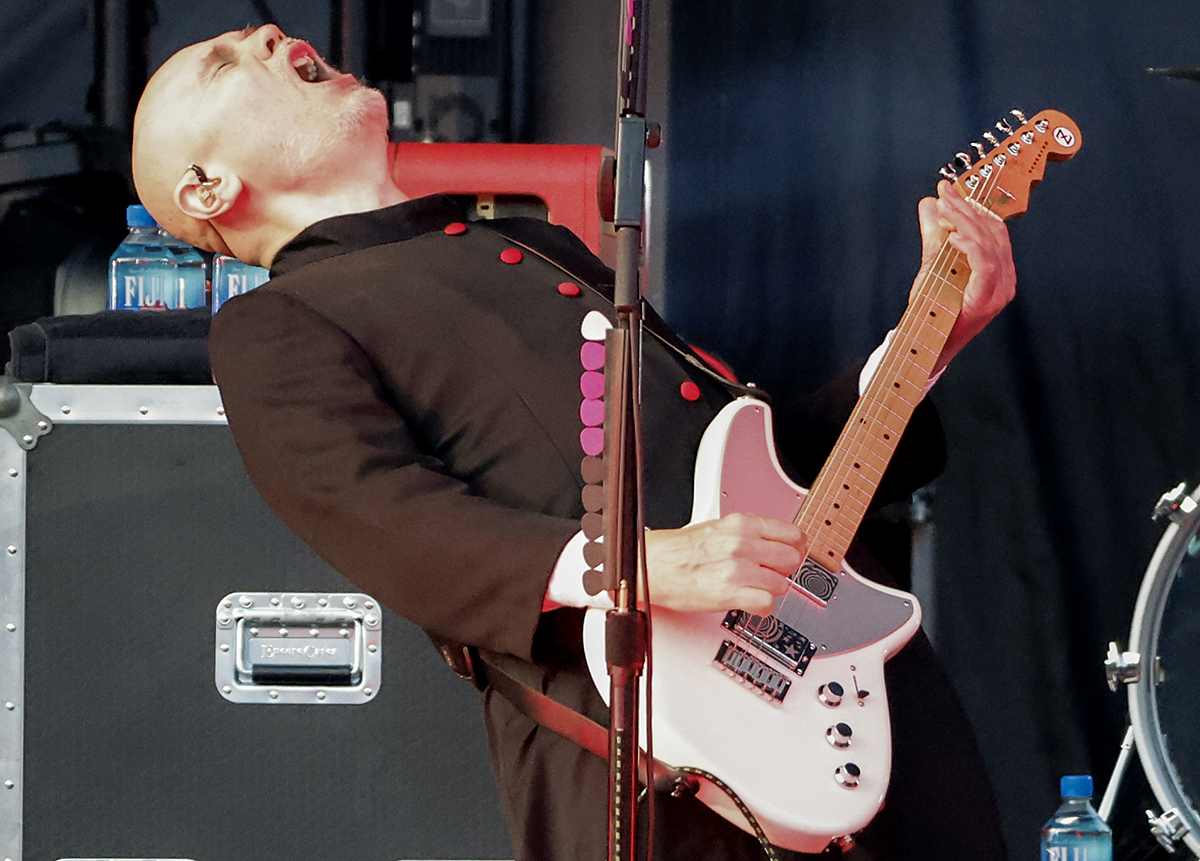

“I was using Strats with Lace Sensor pickups and a weird rack I built that. Somehow, it just worked.” Billy Corgan on 30 years of Smashing Pumpkins’ ‘Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness'

"The record company thought it was the most suicidal career move that you could make," says the Smashing Pumpkins guitarist

In 1993, Billy Corgan’s Smashing Pumpkins dropped Siamese Dream, a quadruple-Platinum alt-rock banger that combined grunge, psych-rock and heavy metal. The result was a swirling epic featuring hits like “Today,” “Disarm,” “Cherub Rock” and “Mayonnaise.”

Despite the album's far-reaching success, Corgan was never one to follow a template. “We weren’t in a social group,” Corgan tells Guitar Player. “We didn’t have a lot of friends. We just went in for months and hatched whatever we were after. And for better or worse, we’d stand there, take the good and the bad, and move on.”

What Corgan was after was something bigger, grander and more expansive than Siamese Dream. After heavy pushback from Virgin Records, he released his vision in 1995: the double-album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness.

Long before then, the Pumpkins’ label, fans and detractors had concluded the endeavor was career suicide. “As you can imagine,” Corgan says. “Before we even started the album, the pressure was really on. If it didn’t sell, you were going to be blamed, as everyone likes to do in the music business when you mess up.

“They like to throw you down a hole and say you should have learned. So, yeah, it was tremendous pressure to live up to.”

Billy Corgan had the last laugh. Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, in all his double-trouble glory, soared to the top of the charts worldwide. Another multi-Platinum award followed, and a cache of beloved songs, like “Bullet with Butterfly Wings,” “1979,” “Jellybelly,” “Tonight, Tonight” and “Zero” became halcyon.

“I wrote, like, over 50 songs for that record,” Corgan says. “It was a tremendous amount of work and a tremendous amount of diversity in the playing and the approach. We worked very hard, and, somehow, it just kind of worked.”

In the ensuing years, Corgan hasn’t run from Mellon Collie’s sound so much as he’s gotten bored with it. The belief is he’s not that person anymore, and that doing things just because they worked once simply isn’t his trip. But the truth is that he couldn’t re-create it even if he wanted to.

“It’s still a mystery to me,” he says. “At the time, it felt like this kind of crazy mess. It was almost like, you now, if you’ve ever jumped off of something really tall — like a diving board — you know that by the time you’re ready to hit the water, and you’ve still got a few seconds to go… that’s kind of what it felt like.”

The Smashing Pumpkins released Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 30 years ago. What does that album mean to you when you look back?

I don’t know. I can’t believe it’s been 30 years. From a guitar perspective, it holds up pretty good. I like the sound of it. It’s a weird sound, but somehow, it sort of works.

Why is it weird?

As far as electric guitars, I was using Strats with Lace Sensor pickups. Plus, I had this kind of weird rack I built that had this very specific sound. But 30 years later, you hear those songs, and they sound good. They still sound like they’ve got a lot of power in them. Sometimes guitar records, as the decades go on, they tend to sound wimpier, for lack of a better word, but somehow that thing holds up.

You mentioned a “specific sound.” Tell me about that.

In the old days, I really liked the James Hetfield kind of scooped mids. I like a lot of highs and lows but scooped out — like the Ride the Lightning sound.

But we haven’t used that sound in forever. I mean, the Mellon Collie sound was very square-wave-ish, and just Marshall preamps cranked to unholy hell, and then I ran it through a bunch of stuff to get more gain out of it. It was basically a rack into a cabinet.

Did you sense that Mellon Collie would be so impactful?

We were so focused on what we were doing; it was really hard to focus on anything else. There was tremendous press on us. Once I told the record company [Virgin] and fought to make the album a double album, the record company thought it was the most suicidal career move that you could make.

The success of Siamese Dream didn’t calm their nerves?

It was like, “How do you come off of a quadruple-Platinum Siamese Dream and basically kill yourself by doing a double album?” They thought it was the stupidest thing in the world. They fought and fought and fought, but eventually I won the argument.

Mellon Collie also went Platinum, but you didn’t stick to that format, either. Looking back, if someone were to tell you that you’d be guaranteed success by following that format, would that appeal to you?

I honestly don’t think you can ever re-create the circumstances of any particular album. I don’t think anything magical would come out of that. It’s about finding something in the moment, and then, by consequence, the public discovering it with you and saying, “Yeah… this is really fresh. We really like what you’re doing here.”

It’s a really causal relationship that’s based on being in the right place at the right time. It’s a romantic notion to think you can re-create something and get the same result. I’ve played this parlor game with a few people through the years talking about it, and I would dare anyone to name one circumstance where somebody went back to the well of “what they used to do” and got the same result. I can’t think of one instance where that’s ever worked.

It's not really possible. Seminal albums like that are a snapshot in time. And you don’t live there anymore.

Nor are we even those people anymore. You go through all sorts of emotions, you know? It’s not like you’re necessarily happy to move on in life because that means things are changing. Change is always kind of intimidating in its own way — but I’m really happy when we look back. We stuck to the plan, which was to always be moving forward. It’s a parlor argument, but I certainly live it.

From a guitar perspective, is there a song from Mellon Collie you're most proud of from a guitar perspective?

I love playing “Jellybelly.” I still think it holds up really well. We played it every night on the Green Day tour, and it’s amazing. You’re playing to 40,000 people, and it would work every night. That’s great to play because it’s so crazy as a composition; I love the guitars and the overdubs. I’m really happy with that.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“What he's playing is often very simple. That's the beautiful thing about David.” Steven Wilson on David Gilmour and remixing the newly released ‘Pink Floyd at Pompeii — MCMLXXII’

“I did the least commercial thing I could think of.” Ian Anderson explains how an old Dave Brubeck jazz tune inspired him to write Jethro Tull’s biggest hit