"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first

Wilson's new solo album is influenced by the experience space travelers have when seeing Earth from outer space

Steven Wilson is well aware that his latest solo album, The Overview, is being touted and celebrated as a return to prog after the many other sonic adventures in his career.

But he's not buying it.

"I kind of avoid the word, to be honest," Wilson tells us via Zoom from London. "I'm extremely wary of the word prog or progressive because everybody has their own idea of exactly what it means. To some people it might mean something very old-fashioned, and of course this album is anything but an old-fashioned record."

Following Wilson's reunion with his band Porcupine Tree for 2022's Closure/Continuation and subsequent tour, as well as on the heels of remixing Yes' Close to the Edge for Dolby Atmos, The Overview conveys the ambitious intent we usually associate with prog. Its 43 minutes are divided into two long-form pieces — “Objects Outlive Us" and "The Overview" — with 10 identified segments between them.

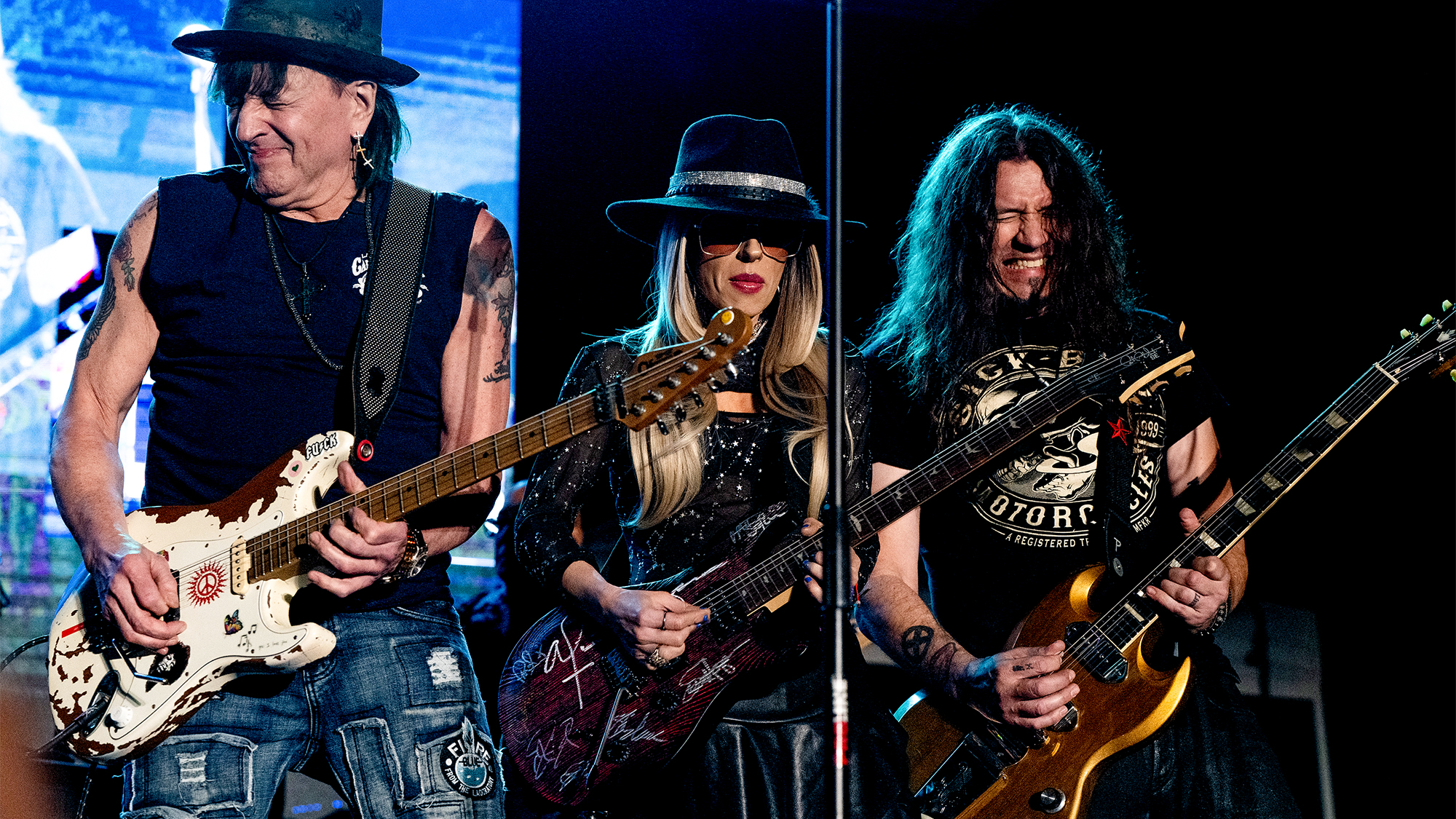

Its theme is the Overview Effect, a phenomenon experienced by space travelers seeing Earth from their unique vantage point, and it is, appropriately, spacey. The soundscape is richly textured and nuanced, with virtuoso playing from Wilson, Porcupine Tree guitarist Randy McStine, keyboardist Adam Holzman and drummer Craig Blundell.

Wilson is also joined on the set by XTC's Andy Partridge, who wrote lyrics, while Wilson's wife, Rotem, provides spoken-word passages.

"The one thing I kind of find myself veering towards more is this expression conceptual rock," Wilson says of his approach to The Overview. "This is a very important distinction to me, the idea that I've returned to the long form. I think that is what people are celebrating, at least some of the people who like that aspect of some of my earlier work.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“There's a lot of musical elements all combining here, and you don't necessarily know where the music is going to take you when you start listening. I suppose that is one of the fundamental hallmarks of what people think of as progressive rock.

"You'll hear Mellotrons on this record, but you'll also hear the latest inversion in instrumentation and digital synthesis for me. It's a lot of things, but it definitely is a return to the long-form, conceptual rock."

Wilson is accompanying The Overview with a full-length film directed by longtime collaborator Miles Skarin, which will also be part of his upcoming solo tour, Wilson's first in seven years. It kicks off May 1 in Stockholm, Sweden, with European dates into mid June and a North American leg starting September 9 in San Francisco and running into October.

You handled the remix of Close to the Edge, then made The Overview — and maybe throw in the Porcupine Tree resumption. Are these interrelated?

I'm not sure about that. I think if you're talking about why this album is in the long form, I think that's because the concept suggested the long form. I wanted it to be about the Overview Effect that astronauts experience in space, and I wanted it to be about this idea of perspective and just how tiny the Earth and the human race are in relation to the universe. To me that immediately suggested something for the long form, a piece of cinema for the ears. It didn't make sense to me be thinking about it in terms of 10 separate songs; it made sense to me that this would be a continuous stream of music.

It's billed as two pieces, but the album really feels like a singular experience.

It's two different sides of the same coin. The first side of the album is really about the human side of it, and the second side is more about the science. And even then, it’s not as simple as that, because there’s little bit of each in both. I think that's the way I kind of rationalize these two separate pieces of music to be. The second half is more about the science and the sheer magnitude of space, and the first is about the human race and its relationship to it.

So how did those perspectives inspire your musical approach?

I think that knowing it was going to be something in the long form straightaway, it's more about how are you gonna take the listener on this journey? You're not trying to create a musical vocabulary for every piece of music; you kind of create some themes and explore those themes from every different angle imaginable. And that's kind of what I did on this record.

So, for example, most of the first side is based on the same 18-note sequence and the same bass line. You hear them in many different contexts, and you may not even be aware you're listening to the same musical motif, but you are. And that's something that you wouldn't normally get to do if you're writing five or six separate songs.

But when you're working in the long form you can take that in more kind of symphonic, classical approach where you have motifs — what Wagner called leitmotifs, what Stockhausen called formulas. That's kind of what The Overview is for me, so that was a different approach for me, one I've not used for awhile.

What's different about exploring that approach in 2025 compared to when you did it before — or maybe even when Yes and others did it back in the 70s?

I think I trusted the fact that I had a sound, and my sound is the result of all the different things I like. So when you listen to my records now you are gonna hear my love of pop. You're gonna hear my love of ambient. You're gonna hear my love of electronic, of post punk, of metal, of jazz, of old school progressive rock, of space rock, of psychedelia. they're all going to come through.

I've been making records for 30 years, so at this stage of my career I don't analyze that, and I don't try to be too self-conscious about what elements I'm putting together.

So this idea that my sound is kind of a hybrid of all the things I like — and, by the way, not only music. I think the biggest influence on this record was also cinema. It's very hard to be writing something about the universe without being conscious of, say, Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey or Christopher Nolan's Interstellar or Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris. They're so dominant in terms of our notion of how we imagine the universe to be and those existential questions that it throws at us.

So I think a lot of the time I had those moves in my head rather than music or musical forms. I kind of trusted that all these different elements of my musical vocabulary would pull it all together. I guess the audience will be the judge of that, but that's the way I rationalize it, anyway.

After 30 years, as you mention, it seems like there's more confidence than rationalization.

Absolutely, and not only for musical reasons but also for reasons I think my listeners kind of expect that now. In a way that's something you have to earn, and sometimes it can take a whole career to earn that from your listeners. I think they know that each thing I'm going to do is going to be a bit different, but it's still going to sound like me at the end of the day, so they're prepared to go with me down these kind of rabbit holes — making an electronic pop record, making an old school conceptual rock record, making more post-punk influenced record.

Whatever it is I'm doing, I think most of the listeners are prepared to give me the benefit of the doubt and also recognize that anything I do ultimately will sound like me and become part of my continuum of work and accept that all these different things are a part of my musical personality.

How did the toolbox expand this time around?

One of the things I love about making records in 2025 is there's never been a more creative time. The possibilities of being creative have never been broader than they are now. We have all this wonderful vintage stuff, stuff from the past, whether it's piano, Fender Rhodes, Hammonds, Mellotrons, analog keyboards.

But we also have all of these incredible, new virtual instruments, digital plug-ins that allow us to twist and mutate sounds. I love it all, and I love to bring it all together. That is what you hear on The Overview.

That's why I would be very reluctant to think of this as a throwback or nostalgic album; it could only have been made in 2024, which is in fact when I made it.

The "Objects Meanwhile" segment of the "first side" seems like a good example of the kind of synthesis you're describing.

I think that's a great example. That's got a big metal riff in the middle of it as well, and it's got psychedelic stuff going around, whizzing. This is what I mean when I say that when I create this stuff I’m not really conscious of how I’m combining all these things. It's a very natural thing to me because I love all these styles, and it doesn't seem strange to me to put them together — at least it doesn't seem strange at the time.

I can retrospectively analyze it, like we are now, and say, "Well, actually that's kind of unconventional to do that," but at the time it's just a very intuitive, unselfconscious, unanalyzed process of me filtering these different things into a piece of music that keeps me interested. When you're a creator you're just trying to keep yourself interested and entertained and engaged in what you're doing, so it's only natural that you would bring in all these things that excite you.

What were you looking for Randy to provide when you brought him in for this?

Randy came in toward the end of the process essentially to be the solo voice when it came to guitar. I played most of the guitar parts myself — most of the bass guitar and most of the keyboards as well — but I wanted solos and I'd left these sort of expanses, and I didn't really know what I wanted but I knew I wanted something that wouldn't be obvious. What I love about Randy is he's young — compared to me, at least — and he is someone that understands the importance of sound in the process of creating a guitar solo.

"I think a lot of old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound."

— Steven Wilson

By “sound” you mean...

I think a lot of old-school guitar players, they can play amazing — beautiful technique, beautiful feel. They can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound, and this comes back to what we were talking about a few moments ago, about how the possibilities for sound now have become greater. And I think Randy understands that. He's somebody that's very familiar with experimenting with pedals, processing, digital and analogue.

And of course the obvious thing to say here is the sound very much affects the way you play, and I think sometimes guitar players forget that — or maybe they don't but the people who listen to guitar players forget that sometimes when you get sound it changes what you actually play.

Randy's a great example of someone who understands that, so we spent a lot of time actually looking for the right sound before we even approached how he was going to play and the kind of scale he was going to play. It was kind of a way to redefine the notion of the classic, extended rock electric guitar solo, and a lot of that was finding the right sound before we even approached what he was going to play.

Are you soloing at all on the album?

I play one very brief solo in the middle of side one, but the rest — there are three big solos — are Randy. I do like the guitar, but it's always been part of my tool box, if you like. My love affair is with making records, and guitars are a part of that.

But when you listen to someone who obviously has a lifelong love affair with an instrument like the guitar, like David Gilmour or Steve Howe, you can feel the integrity and you can feel the passion for it. But when I'm making records, it's pretty much a question of bringing people like Randy, and Adam Holzman, the keyboard player, towards the end to be the solo voices, to provide that more unexpected element — and surprise me as well.

Andy Partridge from XTC is always a surprise when he turns up doing something. How did he become part of this?

I very much think of the album as having themes, to continue with the kind of movie analogy. And for one of the scenes on side one of the album was where I wanted to contrast kind of observational writing — the lives of everyday people living in small towns, the kind of soap operas and small dramas people have every day of their lives — with the biggest kind of cosmic phenomena you can imagine; stars dying, black holes imploding, nebulas dying, this idea of perspective, the great and the small.

And I thought of Andy 'cause for me he's the best, probably along with Ray Davies of the Kinks, at writing observational songs. There's no one better, to me. So I called him up; I said, "Andy, I've got a commission for you" and explained what I wanted. I had a couple of images already in my mind to give him as an example, and he went away and did a phenomenal job and completely nailed it.

What can we expect from the live show when you start touring in May?

The second half of the show is going to be The Overview. I do feel like this is the kind of album I want to play from beginning to end — with the film I've commissioned to go with the piece. So it will be a very visual, very psychedelic, very cosmic experience, hopefully. And the first half of the show will be a journey through my back catalog, and I'm not going to say more than that except I'm looking for pieces of music which perhaps resonate with the theme of The Overview, so other pieces that have perhaps a more cosmic or space-interrelated theme.

"I don't know if we would tour again, but as long as we can find something new that we feel we can do, we'd definitely record again."

— Steven Wilson

Anything ahead for Porcupine Tree?

Well, you know, the band have come back. We had a great time making the record and touring. I don't know if we would tour again, but I think as long as we can find something new that we feel we can do within the context of the band we'd definitely record again.

I've never been one for closing doors completely — even though I did say that about Porcupine Tree before, but that was partly because I wanted people to focus at the time on what I was doing with my solo career. We keep in touch. We're good friends. We've talked about getting together to see what we might produce if we got back together again. So there's no reason to close the door.

Considering Close to the Edge, this was your second crack at remixing the album. What was it like going back, and what was different this time, eight years later?

I think I've learned a lot in the interim. It was an early one for me; very early on in my career as a remixer of classic albums...and the first Yes album I remixed. I was still learning. I was very proud of it, but I think I got a few things wrong in terms of keeping faith with the original mix. It's very important to me to try to respect all of the original decisions made by the original mixing engineers; in this case it was the legendary Eddie Offord, who did a phenomenal mix, and you cannot do better than that.

But of course I'm being hired to create special audio mixes — 5.1 before, and now Dolby Atmos. So I went back and tried to be more faithful to the original stereo mix before I worked in the Atmos realm, and I fixed a few things that I felt had been too revisionist in the [2013] remix. Some people may not be happy about that; they may prefer a more revisionist approach.

But I think my brief, always, in creating spacial audio mixes is to first of all respect the original mix to a point where it's almost interchangeable. With a little more experience this time I was able to do that.

Do you salivate when you get access to those tapes, with all the outtakes and everything from these landmark albums?

It depends if they're any good. [laughs] A lot of stuff that's on master tapes that haven't been released, you can understand why. I've had a few times over the years where I've found absolute gems that haven't been released — a whole Tangerine Dream album that had never been released in 1974, things like that. That's the sort of thing you can only hope for. Yes, specifically, they didn't record a lot that they didn't use. There were no golden-like finds in that respect with Yes.

Which albums would you still like to take a crack at?

Well, y'know, I've always said Kate Bush would be top of my list for remixing in spacial audio. But there are so many; the list is endless. I'd love to do more Floyd; I've just done Pink Floyd at Pompeii [out May 2], which was exciting because Floyd is really my favorite band. I think any artist like Floyd or Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel too, where there's a lot of sound design and a lot of layers and details to the music really lend themselves beautifully to being expanded into spacial audio. I doubt I'll run out of things to want to do, ever.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.