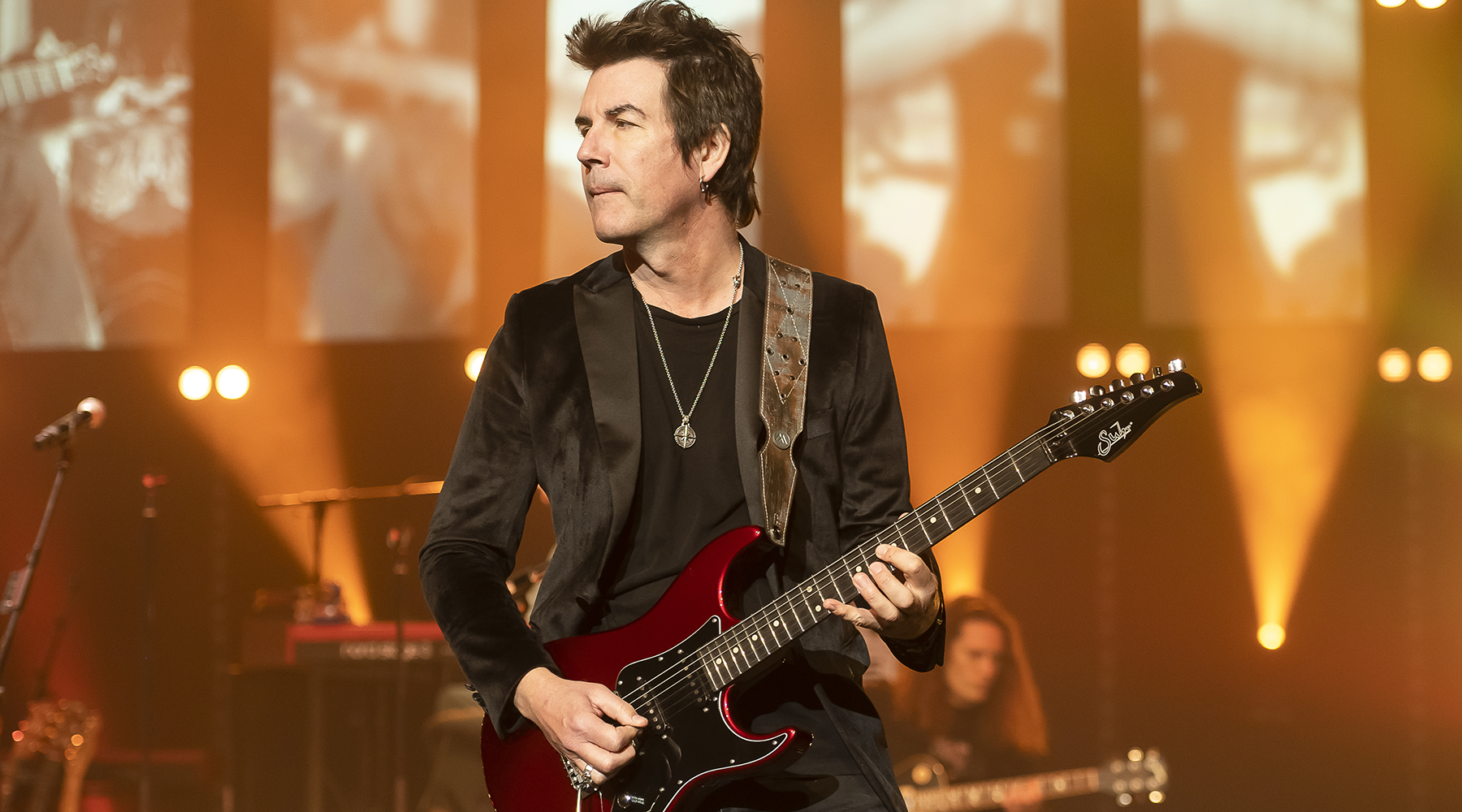

“I played it for Paul Stanley when we were touring with Kiss. He had a look on his face, like 'What the hell is this!?’” Alex Lifeson tells how Rush’s early failure pushed them for their breakthrough success, 2112

The guitarist explains how the band’s more ambitious direction “inspired me to mess around with my guitar tone”

Rush already had one album under their belt when they went into Toronto Sound studio at the end of 1974 to record their sophomore set, Fly by Night. But the Canadian trio's endeavors 50 years ago marked what guitarist Alex Lifeson considers "a new start" for the band.

That year, 1975, featured not one but two impactful studio albums for Rush. Caress of Steel followed Fly by Night's Valentine's Day release by just nine months. It was a one-two punch that put the band on a new creative path and solidified its stature, providing beacons for where Rush would be headed. Key to that was Caress of Steel's side-long, six-part opus, "The Fountain of Lamneth,” which set a benchmark for the following year's triumphant 2112.

"For us it was quite a departure," Lifeson tells us via Zoom from his studio in Toronto ahead of Rush 50, a new 50-track compilation (out March 21) that includes both studio and live takes of the two albums' favorites such as "Anthem," "Fly by Night” and “By-Tor & the Snow Dog."

"We were stretching ourselves more and trying to find somewhere that we wanted to go as a band,” Lifeson explains.

That was made all the more impressive by the fact that, as Lifeson notes, "we were playing 250 shows a year back then. We would be out for three months, come home for a few days and then go back out. I think we spent a couple weeks in the studio on each of those albums. We didn't have much time."

Rush's self-titled 1974 debut and the tour to support it brought about many of the changes the trio would enact for its 1975 releases. The first was the arrival of co-producer Terry Brown late in the making of Rush.

"He saved the first record," Lifeson remembers. "The original mix of the first record was diabolical. It was horrible. We had an in-house engineer/producer, and he mixed it in, I think, two nights or one night or something, and it was terribly disappointing. And we had a couple songs on it that we hated, that we were talked into putting on 'cause they were more 'commercial,’ and all of this crap.

"So we went to Terry and asked if he could remix the record and make it sound more like a rock record rather than this dinky piece of crap that the other guy did. He had the pedigree we wanted. He was English, he came from a very robust musical family environment.

“We went back in to add some things and drop those crappy songs we hated and put in a couple newer songs. And that whole experience with Terry was so comfortable. We didn't work more than a week with him remixing and adding some new songs. It was really the perfect relationship for us. He had great ideas and we could trust him and leave stuff with him. It was a really great, balanced environment."

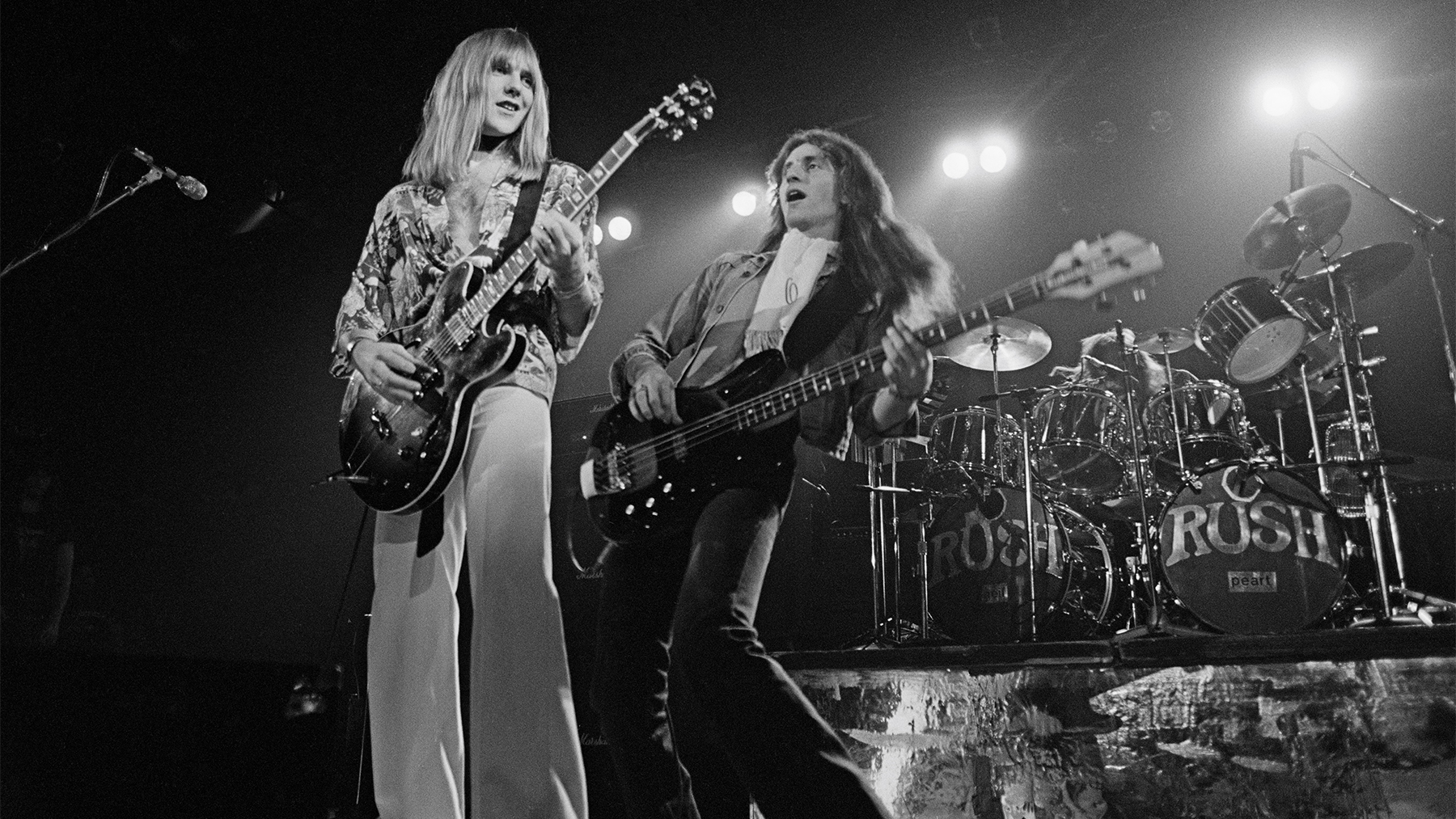

By the time they made Fly by Night, Lifeson and singer-bassist Geddy Lee were joined by Neil Peart, who came onboard in July 1974, during the Rush tour, to replace founding drummer John Rutsey. In addition to his impressive chops, Peart brought his skills as a lyricist. He dipped into the philosophy of novelist Ayn Rand for "Anthem" and created the multi-pronged fantasy battle in "By-Tor & the Snow Dog.”

“After touring for three or four months with Neil, we were so excited to go in the studio and make a record together," Lifeson says. "This was very fresh, very exciting."

Rush had some fairly lengthy tunes under their belt by this point. Rush tracks like "Working Man" and "Here Again" pushed past the seven-minute mark, while Fly by Night's "By-Tor and the Snow Dog” exceeded eight and a half minutes. The group would exceed those lengths on their next album, Caress of Steel. “The Necromancer” ran for 12 and a half minutes, while “The Fountain of Lamneth” extended to 20 minutes. The musical explorations also became more virtuosic and sophisticated, built on suite-like arrangements with intricate parts and changes.

"I think at the time it was just such a progressive rock thing to do these long, conceptual pieces," Lifeson explains. "We were fans of [the Who’s] Tommy. maybe not quite so much of Quadrophenia, and of course Pink Floyd with the way they were creating their records, Genesis with their long, conceptual pieces…

“That's the world we were in at the time. It was always in our blood, I think, to make records that way, more symphonic in concept with longer movements and moving within that context. It's a nice way to approach it."

At the time, of course, Lifeson did not have the arsenal of instruments and other gear that now decks out the wall and floor space of his studio. He owned a Gibson ES-335 semihollow and a 1970 Les Paul Standard electric guitar (he borrowed an acoustic guitar for the sessions), and was using Marshall amplifiers.

"Eventually I started turning things around,” he explains. “Hi-Watt, then back to Marshall and back and forth to other things."

But Lifeson adds that he did not feel at all limited by the smaller "tool box" at his disposal.

"I was getting so many different tones, even then," he notes. "I would think that if you ask any guitarist about their tone, it's not just one tone but a lot of tones. You can have a trademark tone, certainly, like David Gilmour does. But I hear things different for different songs and different ideas. Lyrics inform me, what the bass line is... All that stuff inspired me to mess around with my tone.

"I pulled back my volume on the guitar to around seven for the rhythm kind of playing, then up full for solos. I kind of relied on my hands and the guitar to create the kind of tone I wanted — cleaner. dirtier, whatever. Now, of course, you have so many tools you can create any kind of tones, but I've always really enjoyed that whole discovery of tone, and I was trying out a lot of things on those albums."

Unfortunately, the musical growth wasn’t always successful. The extended arrangements on tracks like “The Fountain of Lamneth" and “The Necromancer" were "something very new to us," Lifeson remembers. "It was, 'How do we put that together?' We were really feeling ourselves out. We were young and just trying to find the direction with that record."

Not everybody liked it at the time, however. Reviews were mixed, and radio stations who had warmed to Fly by Night didn't find Caress of Steel as accessible.

"That record didn't do very well," Lifeson acknowledges. Rush even called its subsequent road trek the Down the Tubes Tour because of the album’s commercial failure.

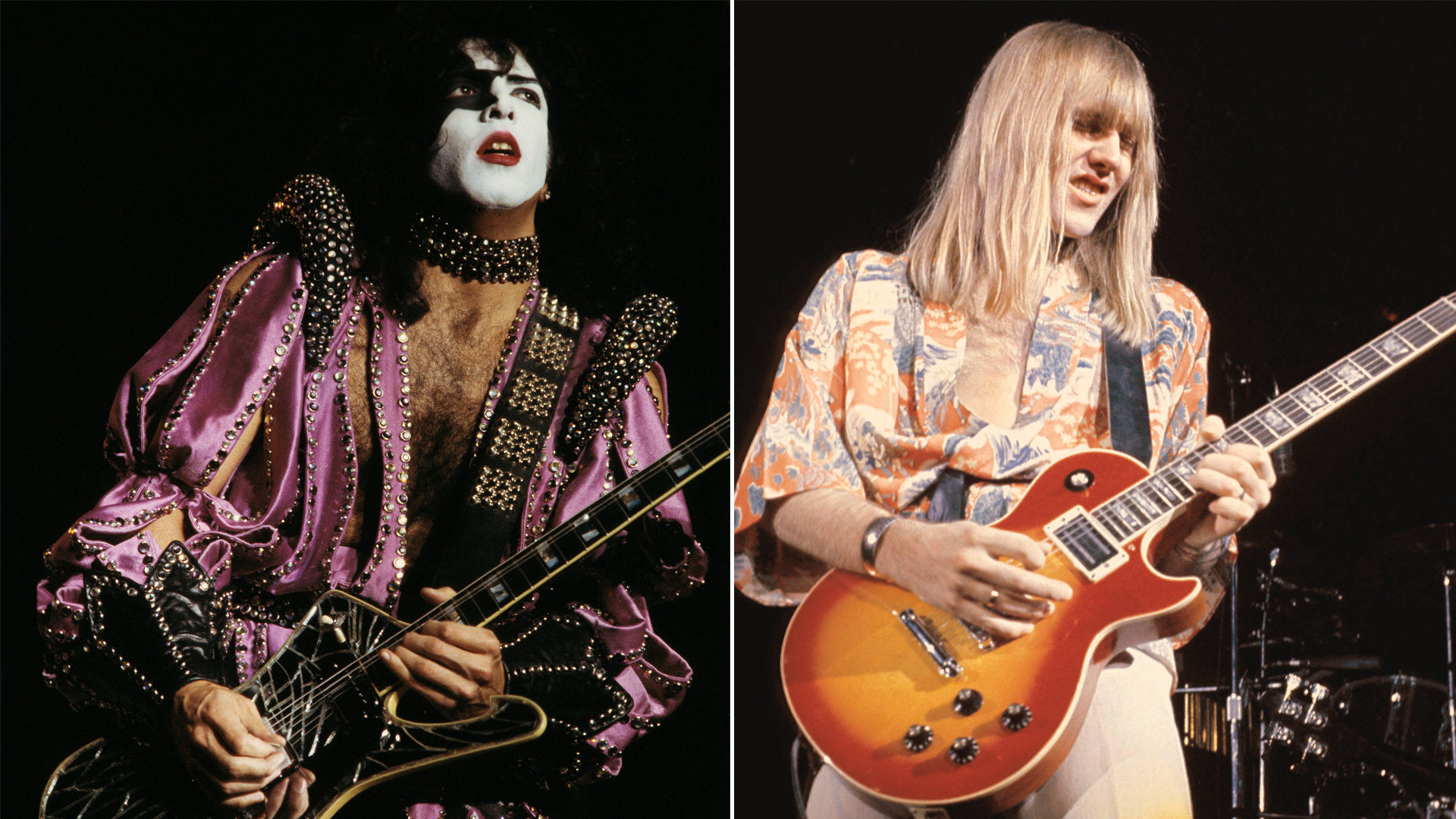

"People didn't respond to it. I remember playing Caress for Paul Stanley when we were touring with Kiss," Lifeson says. "We played it, and he had such a look on his face, like 'What the hell is this?' He started smiling and nodding, 'this is great guys...,' then nodding and quickly leaving.

"We were quite disappointed with that, because we thought we'd made something really, really special.”

But their frustration with Steel’s failure pushed them harder on their next album, 1976’s 2112.

“That's what really informed 2112. We were just doing the same thing we did with 'The Fountain of Lamneth,' but we were more pissed-off,” Lifeson reveals. “It was, 'We're gonna do this, and if it doesn't happen we'll just go home and get jobs, I guess. At least we'll go down in flames, fighting.”

2112 did indeed right the course — eventually, as it took awhile to gain momentum — and Rush maintained a steady and ambitious course until it ceased in 2017, with more side-long and conceptual work throughout.

"We were always about exploring and changing," Lifeson explains. "We didn’t really want to be just one thing. We always wanted to move forward from the last thing we did. that was part of that whole mindset."

Brown remained the band's "fourth member" through 1982's Signals and remains a friend, working on remixes for archival releases. Lifeson and Lee have remained best friends since Peart's death in 2020. They’ve performed together at special events — the South Park 25th Anniversary Concert and the Taylor Hawkins tribute concerts, both in 2022 — and still jam with one another, privately. Lee told Rush's story in his 2023 memoir My Effin' Life (his next book, 72 Stories, is due out June 10), Lifeson is part of the band Envy of None, whose second album, Stygian Waves, comes out March 28.

"I go over to Geddy’s house quite often," Lifeson says. "We're just gonna jam and cuck around. We wind up sitting on the couch and drinking coffee and laughing. That's our relationship, best buds.

“We'll always play together. We'll always do something musical together, I think. It doesn't matter whether people hear it or not."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first

“It's past 2 billion plays on Spotify… which makes my guitar riff one of the most-played in history!” Andy Summers reveals his role in the making of the Police hit “Every Breath You Take”