“I often wish guitarists wouldn’t play the same stock chord voicings and licks.” Here are seven ways guitar players can improve — according to professional bassists and drummers

From volume control to tone and rhythm — every guitarist can up their game with these tips from the people who work with them

So you think your bandmates are happy with your contribution as guitarist? That you’re doing a great job and everything is peachy? Well, I conducted an expansive investigation to find out just what they’re whispering to each other when we guitarists aren’t around. This is information you need to know if your goal is to be a sought-after working musician — or if you just want to stop driving your bandmates crazy. Or even just really impress them.

The idea for this piece hit me when an old bass-playing friend contacted me over the holidays to purchase a block of lessons as a gift for the guitarist in his band. He presented a long and well thought-out list of grievances, ranging from “his tones are awful” to “he plays too loud and doesn’t pay any attention to the rest of the band’s feel.” He ended with an exasperated, “He just won’t listen to me.”

Sometimes it’s difficult to look in the mirror and be honest with ourselves about where we could use improvement as guitarists. So I sought out advice from some great bassists and drummers to get their points of view on how guitarists can become better bandmates. The players I interviewed are all successful working musicians who have had countless experiences interacting with guitarists in all types of situations.

The key here is not to take criticism personally. And while I’m sure we could tell bass guitar players and drummers a thing or two, let’s sit back, take a deep breath and be open to improving our game, whatever level we may be at.

Watch Your Stage Volume

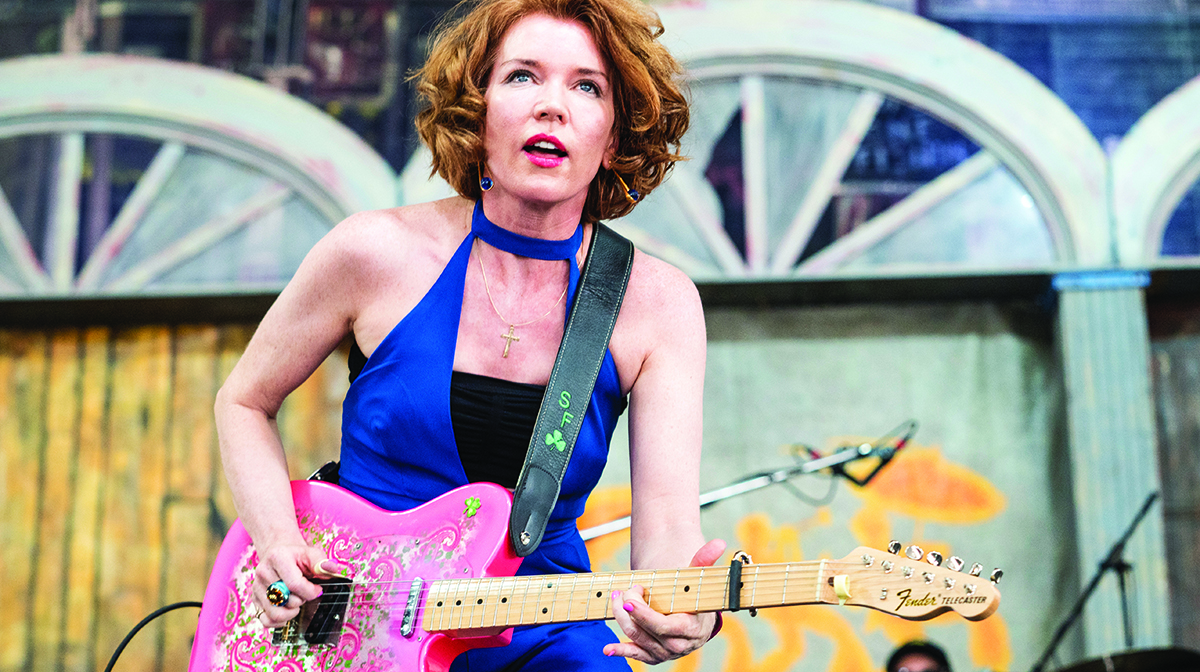

Cat Popper has been a sought-after bassist for many years, performing with everyone from Willie Nelson and Levon Helm to Jack White and Ryan Adams. She began our exchange by offering advice for electric guitar players about how to set our stage volume.

“Keep in mind that with blaring stage volume comes low-mid frequencies that can screw up lower-voiced singers and, definitely, the bass guitar, especially when there are keyboards or piano onstage,” she says. “There are many gigs I’m at where I know I won’t hear myself much at all — because if I turn up, it starts a stage-volume war, and the house suffers.” Sounds like we can be more aware that our volume and tone choices impact our band.

Cat also wants us to know, “I am listening to your solos and accompanying you! I got your back!” In turn, let’s pay more attention by listening to what’s going on around us, and consider what our bandmates are playing when we create our own rhythm parts and solos.

Quit Playing the Same Old Things

Jon Price is a veteran of the New York City live music scene and a rock-solid part of any rhythm section and a brilliant improviser. Jon offers this piece of tasty advice. “I often wish guitarists wouldn’t play the same stock chord voicings and licks,” he says. “It’s good practice to ensure you are hearing an idea before you start playing it, otherwise you just end up playing something similar to what you’ve done countless times before.”

And how about putting the guitar down and using your head? “I encourage players to literally not hold the guitar when they are coming up with a part. Listening and hearing, even singing, an idea is essential, rather than just letting your hand position dictate what idea you’ll come up with next.”

Practice As If You’re Onstage

Jon also stresses how we can be better prepared for performing. “When you’re practicing, make sure you set up all the elements as close as you can to the upcoming live situation.” This means practicing standing up, if that’s how you’ll be performing, using the same guitar, and even singing into an unamplified mic, if you’ll be contributing vocals. These “dress rehearsal” elements all contribute to helping you acquire the desired muscle memory for the upcoming performance.

Ryan Vaughn has been a freelance drummer for over 20 years. His credits include expansive TV work such as The Masked Singer, Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist, and most recently as the house drummer for ABC’s The Bachelor Presents: Listen to Your Heart. Like Jon Price, Ryan brought up gig preparation — or lack thereof — as a problem.

“The biggest thing that I notice in young players is a general lack of ‘homework’,” Ryan says. “Lots of players can play, but very few truly prepare for a gig.” He encounters this often when playing gigs featuring cover material or songs by well-known artists. “Young players often don’t really spend time dialing in the sounds from the records that they are learning. In contemporary pop-rock music, sounds are everything.” (Ah, so we shouldn’t just buy the effects, we have to actually learn how to use them? Point taken.)

Be Prepared

Ryan concludes by adding, “No one really cares about the gear or the chops a player might have. It always comes down to their preparedness and ability to make the band feel like they are living in the sound of the recorded songs that they are recreating live.” I learned early on just how awful it feels to be unprepared in rehearsal or onstage, and this can leave a lasting impression on other musicians. That’s not great if you desire a career in music. Using some of your practice time to fully prepare for a gig will always serve you well in the end.

Know Your Pedals

Julia Adamy is a bassist with an extraordinary list of credits. She has performed at illustrious New York City venues such as Carnegie Hall and Radio City Music Hall, done TV work like The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel Live and The Today Show, and been a member of the pit orchestra for major Broadway shows such as Hamilton, Mamma Mia! and more.

Echoing Ryan Vaughn, she points out, “Some of the most creative players have a strong pedal game! Spend some time getting to know the ins and outs of effect pedals so that you know the full capabilities of them individually and paired together.”

Get a Feel for Feel

As for feel, Julia advises, “Really work on pocket and being intentional about where the groove is placed, practicing along to records that feel good to you and trying to dissect where in the beat they’re playing.”

Not surprisingly, this emphasis on “feel” in relation to rhythm and time was also addressed by some of the drummers I spoke with. Understanding these concepts is a key element of what makes great players sound so good.

Elliot Jacobson has drummed with many artists, including Elle King and Ingrid Michaelson, and is also a busy session player. “Feel — in terms of straight to swing, on top of the beat to behind the beat — has always been huge,” he says, “the way playing 16th notes can sound so different from player to player, and how some players can’t adjust their feel at will.” This inability to adjust will inspire rancor from producers and bandmates alike, and conversely, having this skill will make you stand out in the crowd.

As Julia Adamy recommends, one way to accomplish this is to play along with your favorite records while focusing your attention squarely on the feel created by the bassist and drummer — as if they’re actually in the room with you. You can also watch any number of great videos where drummers and bassists talk about and demonstrate how to approach different feels and tempos.

Consider Yourself Part of the Rhythm Section

An accomplished drummer, Stephen Chopek has toured and recorded with artists such as John Mayer, Charlie Hunter and Jesse Malin. He’s also a power pop singer/songwriter, who plays all the instruments on his 2021 EP, Dweller. Here, Stephen takes us a step further inside the concepts of feel and time. “First and foremost,” he says, “consider yourself a rhythm guitarist and member of the rhythm section. Keeping good time doesn’t mean you have to play mechanically or sacrifice good feel, and the best ensembles are those that are all feeling the time together.”

He implores us to be an active part of creating a song’s tempo and feel, and indicates that it shouldn’t all fall to the drummer. “The role of timekeeper shouldn’t fall solely on any one member of the band. That’s a lot of weight to put on one person’s shoulders, and if one player is feeling overburdened or stifled by the responsibility of having to do someone else’s job, the whole group will suffer.”

Stephen also points out some of the lingo we might recognize but not fully understand. “There’s a lot to be said for knowing how to play on the beat, behind the beat or ahead of the beat,” he says. “A more helpful way to conceptualize these ideas is to play within the beat. Find where it is as a band and sit inside of it. As with most things, this is easier said than done!” That said, to accomplish this, Stephen recommends using a metronome when practicing — but he knows that some will be turned off by this advice. “If a metronome isn’t your thing, then set up a few loops and apply some practice routines to them at different tempos.”

Again, digging into some YouTube videos will reveal a wealth of information and make these concepts seem not so esoteric. Feel is somewhat esoteric, but that’s the nature of music and what makes it magical. The best musicians are in touch with how to actively contribute to creating this magic in an ensemble setting, and by simply making yourself aware of these concepts you’re taking a huge step toward achieving this goal. As Stephen points out, “The only way to get better at playing with other people is by playing with other people!”

So, in the end, are we perfect? No. But working toward being more skilled as bandmates and listening to others in the verbal and musical senses will help make articles like this no longer necessary!

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band