The Art of Classical Guitar: Expand Your Skills with This Fingerstyle Tremolo Picking Technique

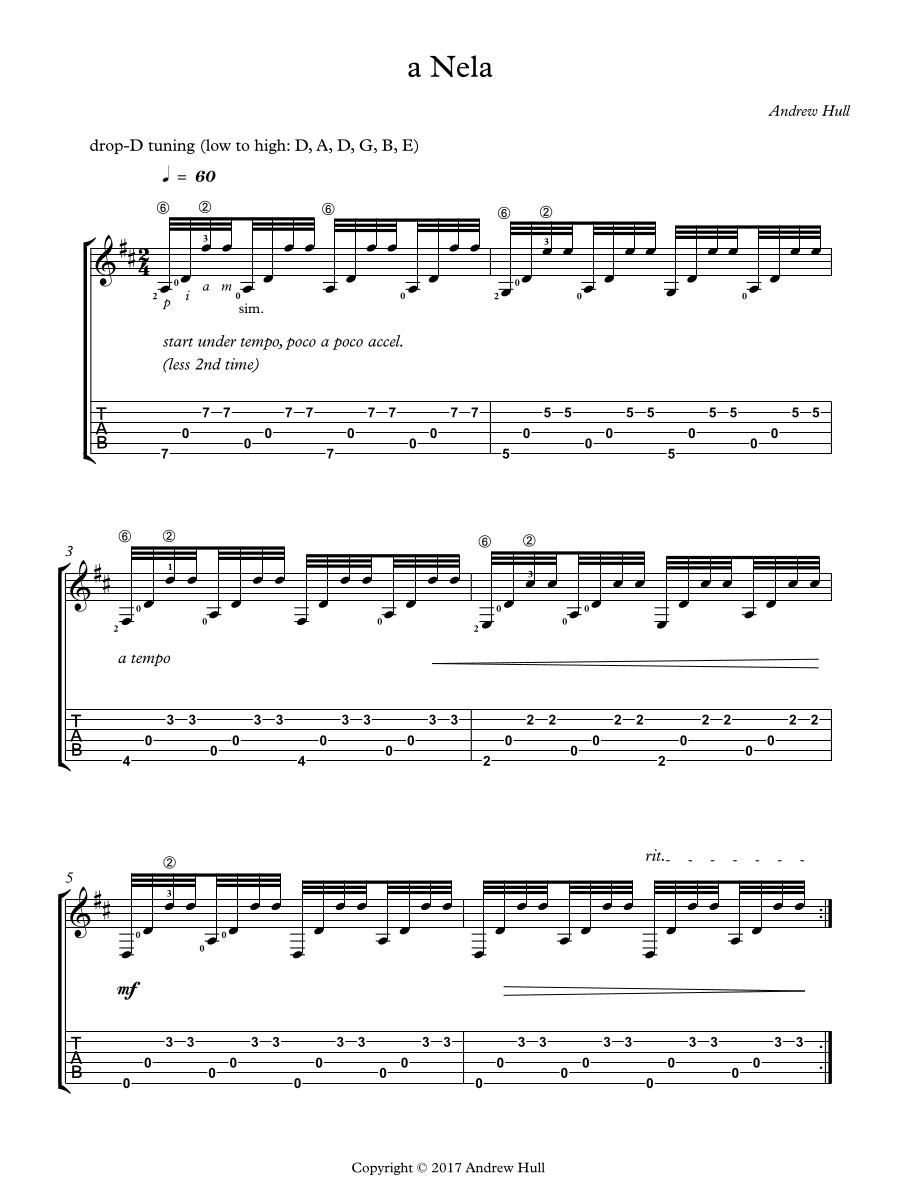

Learn the beautiful composition “a Nela” from the composer himself – classical guitarist Andrew Hull.

Outside of monks, there is no more noble vow of poverty than that accepted by the classical guitarist. You’ve seen us performing at your local wedding ceremony or busking on the subway platform, or maybe we’ve served you at Starbucks, gazing blissfully into the distance with images of Carnegie Hall dancing in our heads (you can spot us by the long fingernails on our right hands).

When you owe nothing to anyone, you can do anything.

Like those humble hermits of lore, our detachment from both popular culture and the pursuit of the all-mighty dollar has given us access to moments of true beauty and, dare I say, great art. When you owe nothing to anyone, you can do anything. And so, without any concern for trends, and in the spirit of sharing something I’m personally very proud of, I present an original solo guitar composition of mine entitled “a Nela,” which I perform on a nylon-string guitar in the classical fingerstyle tradition, but with a novel twist that involves an unorthodox but highly effective tremolo-picking technique.

The inspiration for this little gem came to me while studying in Uruguay, a quiet little South American country nestled between Brazil and Argentina. When I first arrived there, I stayed with a friend’s aunt, whose name was Nela. She was serene, kind and generous. This piece is a mirror of that time.

The Pattern

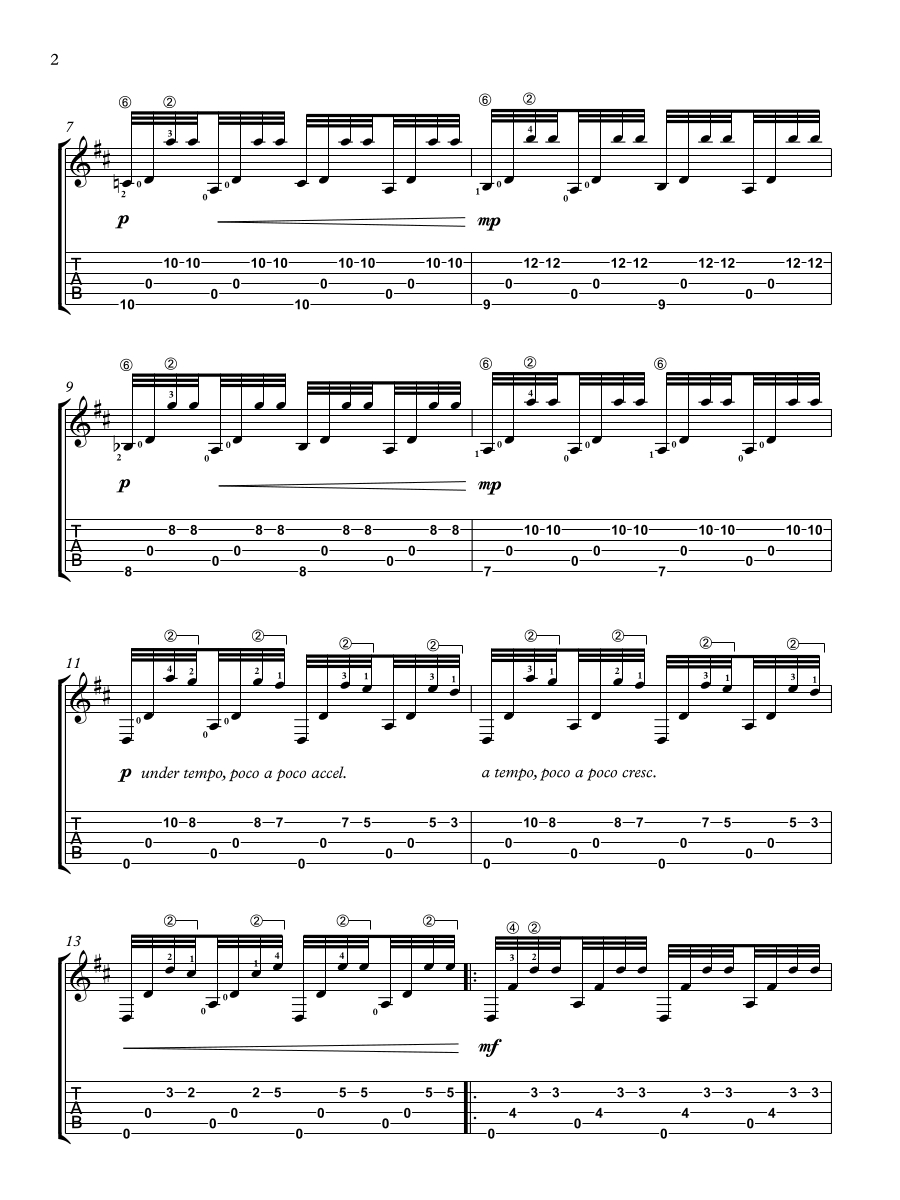

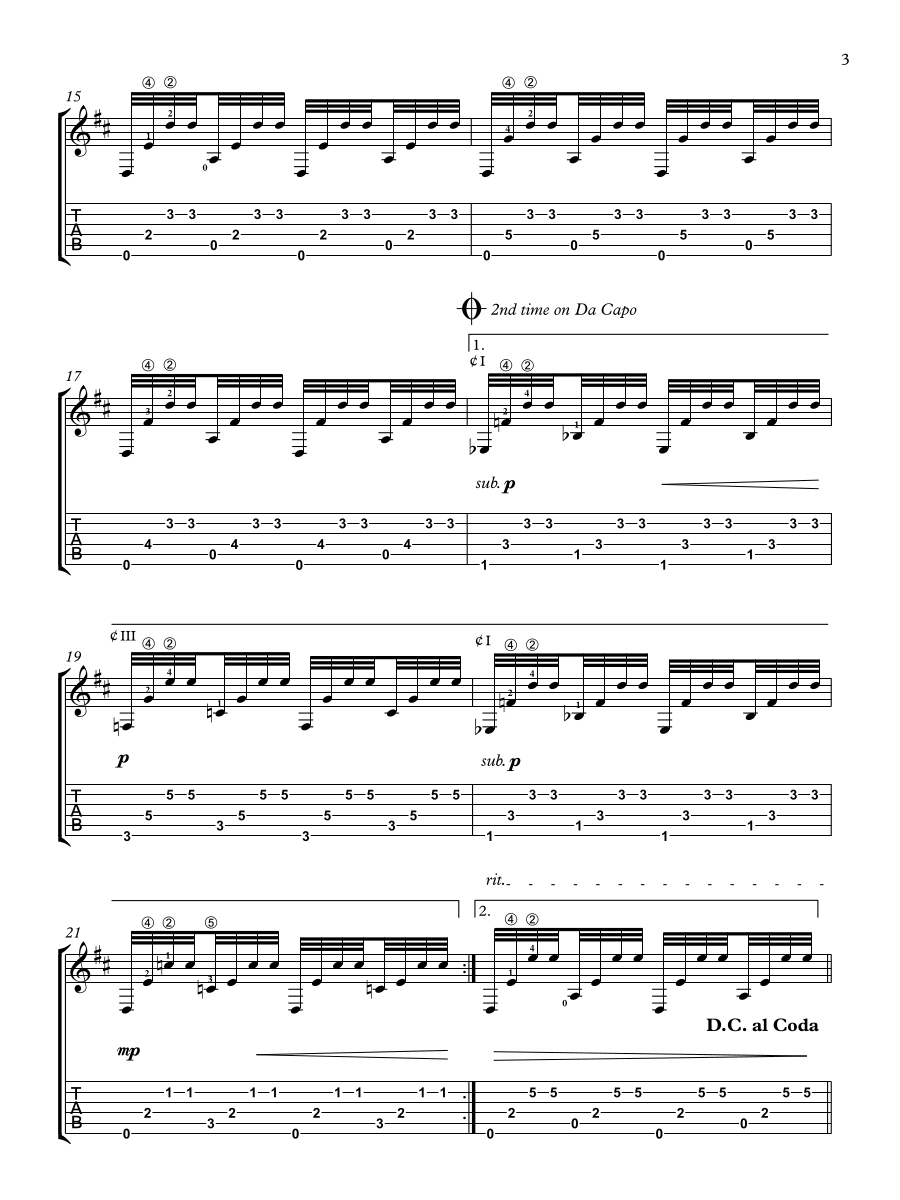

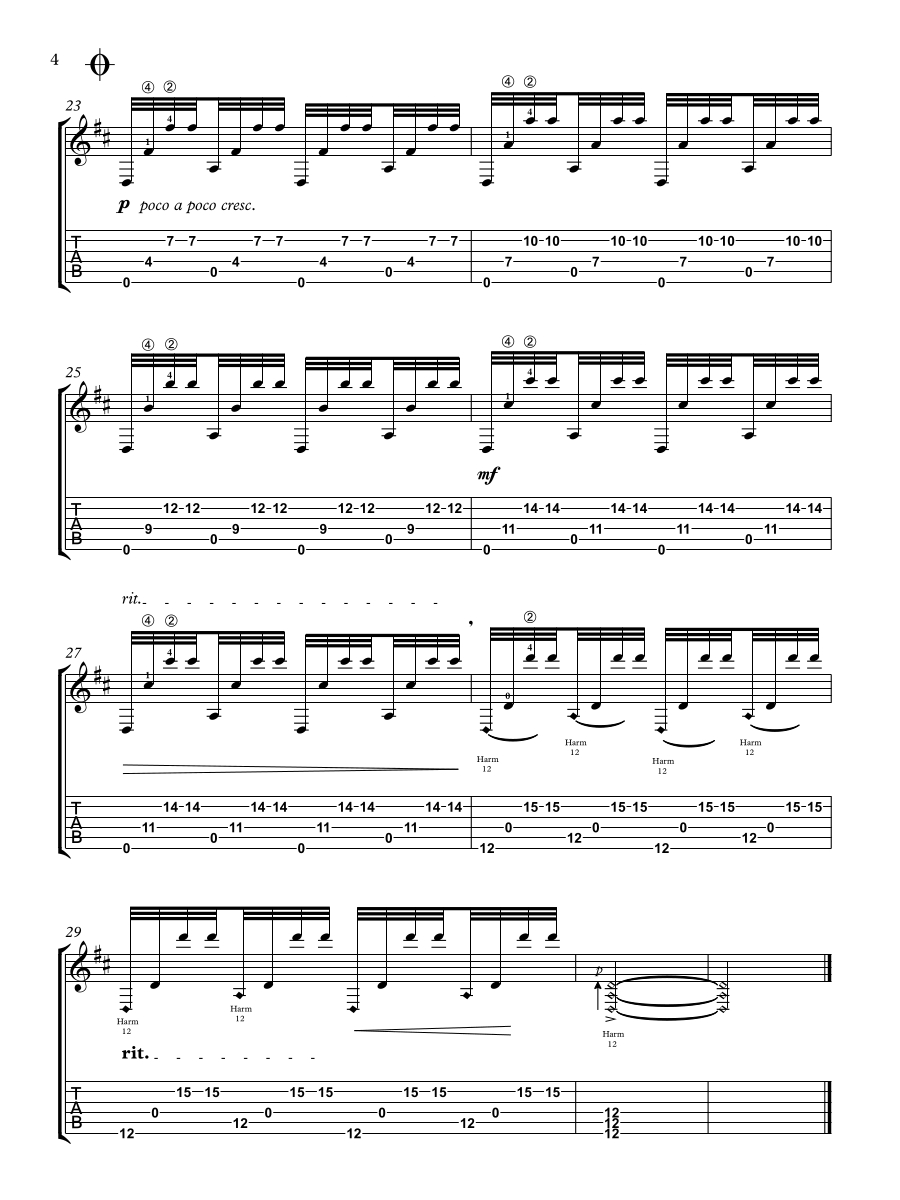

The key recurring technical element of this piece, which is performed on a nylon-string acoustic guitar in drop-D tuning (low to high, D A D G B E), is the repeating right-hand fingerpicking pattern p, i, a, m – or thumb, index, ring, middle. At its base, the sequence is a modified tremolo. Tremolo is a flamenco guitar technique that customarily involves picking a bass note with the thumb, followed by a melody note on one of the treble strings that is quickly rearticulated three times, which creates the aural illusion of a single held note that can be used to emulate the lyrical sustaining tones of the human voice or an instrument such as the flute or violin. The sequence is then typically repeated with single bass notes moving across the bottom three strings, one note per string, to form slow-moving arpeggios beneath the tremolo-picked melody.

The tremolo I employ in “a Nela” is a truncated variation of this traditional technique, for which each high melody note is picked only twice instead of three times. This similarly produces a satisfying sustained-note effect, and it’s a little easier to do. It also frees up your right-hand index finger (i) to pick an additional arpeggio note, which throughout the piece is the second note of each four-note group, consistently performed on the 4th string (the “regular” D string).

Tremolo is a flamenco guitar technique that customarily involves picking a bass note with the thumb, followed by a melody note on one of the treble strings that is quickly rearticulated three times.

For any arpeggio-based technique – and this also applies to approaches like sweep picking with a plectrum and tapping on electric guitar – you have to fully internalize the pattern to the point where you can forget about it and make music, and the only way to do this is through repetition. The first step is to separate the hands, as a preparatory exercise. For a right-hand arpeggio like this, you’ll want to mute, or dampen, all the strings with your left hand while picking out the pattern with your right. Do this a few times to see how the basic pattern plays out and feels, as you adjust your pick-hand posture.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You’ll find that this approach is helpful and beneficial because, when you’re playing normally, the strings themselves are moving. As a result, you’re literally trying to hit a moving target at high velocity, which isn’t easy. Muting, or muffling, the strings will immobilize them and allow you to concentrate on finger placement and acquire accurate muscle memory. Once you get that four-note “roll” flowing, work on adding the notes, and be mindful of not sounding any unintentional notes on unused strings.

So how long does it take to master this technique? Days. Do it while listening to music, reading a book or streaming your favorite show.

Muffling the strings while honing the mechanics of the combined arpeggiation and tremolo picking also makes it easier to hear if the pattern is even or not. There’s a common tendency with the tremolo technique to sweep through it with the right-hand fingers, which can create a lopsided, galloping effect, which is not the object here. For some great samples of how to make a tremolo pattern sound even and singing, take a listen to Pepe Romero’s or John Williams’ performances of Francisco Tarrega’s “Recuerdos de la Alhambra,” the most famous and celebrated example of tremolo picking in the classical guitar repertoire.

So how long does it take to master this technique? Days. Do it while listening to music, reading a book or streaming your favorite show. You need this technique to become like typing, where you’re thinking about the words and not the individual letters. It needs to become second nature.

Starting the Piece

I’ve attended a lot of classical guitar masterclasses. I saw Julian Bream back in the day, watched and played for Christopher Parkening, Pepe Romero and Eliot Fisk. Giving master classes is the cash cow for any classical performer, but the term is a bit of a stretch when extended outside a small group. “Performance class” would probably be a better term. Otherwise, there must be tens of thousands of “master” classical guitarists out there.

That aside, one thing I’ve seen over and over again is the “first-note move,” where the teacher won’t let the performer get past the first note in the piece. It’s a cruel lesson in how master classes work, and it happens in one way or another in every master class. Essentially, the poor kid gets onstage and begins to play, thinking he or she is going to perform the entire piece and then receive some advice. Instead the student plays one note, or maybe a phrase, and the teacher stops the performance, asks the student to do it again, and then again, and again, and again. (This kind of agonizing scenario was dramatized, in a jazz drumming context, in the 2014 movie Whiplash.)

For this piece, you’ll want to create an ambience of serenity while implying a quiet, confident virtuosity.

Unnecessary intimidation and public-humiliation issues aside, the point is to teach the student there is more to the piece than the execution of the notes, as if to say, “all of your preparation was meaningless if you can’t create an entire universe with that first note.” Or put another way, the teacher is implying, “I could get up onstage and play a simple major scale and get more audience response than if you got up there and played Bach’s entire Chaconne.”

So how does this pertain to “a Nela”? For this piece, you’ll want to create an ambience of serenity while implying a quiet, confident virtuosity. Listen to the audio recording (above), and you’ll notice that I create this in my performance by sitting on the first bass note for a moment. The idea is to mark the beginning, to let you know the piece has begun. And so I start well below tempo, so you can hear how cool the arpeggio is. I then proceed to slowly ramp it up so that you can feel how exciting my tremolo technique is and how easy I make it sound. I’ve made a musical and technical statement and done it in such a way that I can hit it every time, even just rolling out of bed on a Sunday morning. Which leads us to the next topic, CCRs.

CRRs

Can’t-Cut-it Rubatos. I was introduced to this unofficial, humorous term back in college by a fellow classical guitar student from North Carolina. Rubato is a composer’s performance indication in sheet music that tells you that “it’s okay to take liberties with the rhythm by stretching and/or compressing it” (slower or faster) as you see fit, then “give it back” later in the phrase. Essentially, I’ll speed up here, knowing that I’ll slow down later, and it’ll all even out in the wash.

A CCR is a special kind of rubato designed to help you deal with the stuff you can’t play. There are many pieces in various musical styles that have this kind of technically dicey passage. And all too often we get caught up in the ego trip of attempting to rip through a piece with the fantasy that we’ll be raising our hand at the end like Jack Butler, getting kudos from Legba and sending Eugene back to the woodshed (as in that other cool musician movie, Crossroads, from 1986).

Take a good, close listen to any of your guitar heroes and you’ll see how they slow into the tough stuff, then catch up on the back end, all under the guise of “artistic expression.”

But that doesn’t usually happen. Most of the time, when we “go for it,” we end up biffing it, don’t get the gig or lose the competition (I’ve done this spectacularly, by the way) and have to go back to the woodshed alone. So why not ease into the tough stuff and catch up late in the phrase?

A perfect example here is bar 11, wherein my modified tremolo pattern is used to execute a descending tremolo scale. At tempo, this is a very difficult move to execute cleanly and consistently. Played that way, it’s not as musically satisfying either. But with a little CCR, which I’ve indicated with the direction “under tempo, poco a poco accel.” (English translation: “accelerate, little by little”), what was once a terrifying trapeze act becomes a sublime moment.

That’s the best kind of CCR – one that feels like some deeply felt emotion plumbed from the depths of your being. Take a good, close listen to any of your guitar heroes and you’ll see how they slow into the tough stuff, then catch up on the back end, all under the guise of “artistic expression.”

Last Notes On Metronomes

If you want to play a solo piece like this well, kill your metronome. The beauty of playing solo classical guitar is that, since you usually have an infinitesimally small audience, and no one wants to dance along – really, they don’t – you have incredible freedom with the tempo. It’s art music, for crying out loud. That means you have absolutely no responsibility to be strictly in time.

In fact, because of this, you have more freedom than any other guitar player on the planet. Don’t give that up to a metronome! A metronome is a great tool that has very worthwhile uses, namely as a pace setter and challenger for technique exercises, a progress checker, and, of course, a reliable reference for a given tempo. But it’s not an end in itself. To illustrate, let me offer the following analogy.

Ideally, on a piece like this, the tempo is elastic and constantly fluctuating, ebbing and flowing like waves on a beach, along with the volume, or dynamics, building and crashing down and then retreating once more.

The reason something like a Peloton, which is essentially an exercise metronome, works well for many people is it gives you a reason for all of the pointless exercise – competition. You’re able to measure yourself against others in some way other than appearance (i.e., the traditional goal of exercise). This is an important insight because no amount of exercise will make you classically beautiful. That’s based on some fairly set proportions that you are either born with or not. There may be something secondary to glean here, like “your scales are fast, but I don’t care to hear them.”

Ideally, on a piece like this, the tempo is elastic and constantly fluctuating, ebbing and flowing like waves on a beach, along with the volume, or dynamics, building and crashing down and then retreating once more. In the final analysis, the tempo should average out to whatever it should be overall. So, by all means, check that metronome so that you can feel that pace that you’re dancing around. But, for God’s sake, don’t let that computerized click dictate what you do here! It’s not worth it, especially when you’ve taken this vow of poverty we call classical guitar.

Andrew Hull is a Guitar Foundation of America International Competition Finalist and Fulbright Scholar (Uruguay, Abel Carlevaro). A graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory (Dusan Bogdanovic), Andrew also studied at the University of Arizona (Thomas Patterson) and USC (William Kanengiser/Scott Tennant) and did preparatory study at CalArts (Stuart Fox). His 7 Family Miniatures were recently published by Productions d’Oz, and his 7 Studies for Guitar are available from Mel Bay Publications.