Take a Mindbending Journey Into the Adventurous and Experimental Style of Psychedelic Guitar

Tune up and turn on as we explore the far-out sonic landscapes created by legendary players such as George Harrison, Keith Richards, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix and more

It was the 1960s, and everything was groovy. Musicians pushed the boundaries of sonic expression and experimentation, with guitarists boldly leading the way.

The hallucinogenic effects of mind-altering drugs, most notably LSD, are credited to have contributed to the creation of a new “psychedelic” sound, with guitarists developing a unique and colorful palette of fuzzed-out – and sometimes just plain weird – tones, inspiring generations of players to come.

While we don’t encourage you to indulge in hallucinogenics, we do suggest you grab your guitar, as we begin our adventure into psychedelic guitar playing.

One simply cannot revisit the 1960s without paying tribute to the Beatles, who began as a mop-topped pop quartet, but soon morphed into a psychedelic songwriting juggernaut with multiple iconic album releases spanning 1966 and 1967, including Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour.

On 1966’s Revolver, George Harrison can be heard going into full bizarre mode, adding time-warped backward guitar (lead guitar lines that are recorded and then played backwards during the song) on “I’m Only Sleeping.”

In addition, Indian music’s heavy influence on Harrison and the psychedelic sound in general can be heard in his sitar-like motifs from “She Said She Said,” also from Revolver.

See Ex. 1 for a riff inspired by this song, and pick near your guitar’s bridge to emulate the sitar’s timbre.

Along with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones ventured into this brave new world with album releases like 1967’s Their Satanic Majesties Request, featuring the track “2,000 Light Years from Home.”

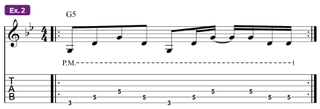

After a 40-second intro of some rather terrifying processed atonal piano musings, Keith Richards enters with a palm-muted single-note guitar riff, which sounds as if it could be the persistent ticking of a clock from an imaginary episode of the bizarre 1960s TV series The Twilight Zone. (In fact, a similar guitar line, albeit less rhythmical, appears in the show’s actual theme music.)

No fuzzy tones here – Richards simply goes with an understated clean electric guitar sound, allowing the staccato jabs of his palm-muted notes to do the talking.

See Ex. 2 for a line inspired by this same track.

Try moving it around the neck in various keys and octaves to experience different shades of mystery.

March 1965 was a monumental month for the up-and-coming British guitarist Jeff Beck. Upon Jimmy Page’s recommendation, Beck was asked to join the Yardbirds, famously replacing Eric Clapton.

Those were big shoes to fill, but Beck did not lack confidence or imagination. And while his stint with the band lasted just 20 months, his influence from this period, as well as his solo career that followed, would be felt by scores of guitarists.

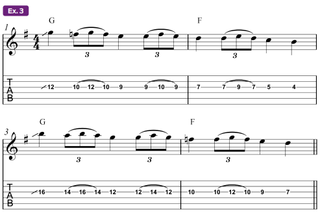

A great example of Beck pushing sonic boundaries can be heard in the Yardbirds’ 1966 single “Over Under Sideways Down.”

Here the guitarist adds a wildly strange melodic motif, which, while initially met with some skepticism by his bandmates, came to be widely regarded as the song’s signature hook.

Beck combines some deft single-string playing with a gnarly tone. See Ex. 3 for a similar line, inspired by this song.

The next stop on our magical musical tour brings us to the legendary Jimi Hendrix. His trippy songwriting combined R&B-influenced rhythm playing with soaring guitar solos, steeped in blues and drenched in fuzz.

Jimi somehow managed to control, at will, the beast that is amplifier feedback, creating new tripped-out sonic journeys for his audience.

Hendrix regularly summoned, as if by magic, all manner of new sounds from his guitar. With the song “Fire,” from the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s debut 1967 album, Are You Experienced, he introduced himself with a guitar solo consisting of a veritable onslaught of stinging string bends and vibratos.

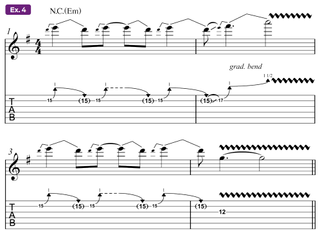

Ex. 4 brings to mind this face-melter. Note that I’ve added an octave-up doubling effect to further capture Jimi’s sound, as this is something he employed frequently via his Octavia pedal.

This pedal, designed specifically for Jimi by his sound technician, Roger Mayer, doubled every note one octave higher, while adding fuzz. It often sounded as if Jimi’s guitar was tearing apart at the seams.

While discussing Jimi, let’s give a nod to another great guitarist from a later generation who was influenced by Hendrix’s psychedelic sound, namely Prince, whose musical legacy continues to live on despite his untimely death in 2016.

An iconoclast, Prince often fused his R&B/funk/soul foundation with elements of pop, rock, jazz or whatever suited him in the moment.

One of his 19 top-10 hits, the single “When Doves Cry,” off of 1984’s smash album, Purple Rain, went to number one on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, where it stayed for five weeks.

Prince notably played every instrument on the track. The song bursts through the speakers with a virtuosic unaccompanied electric guitar line, which seems to answer the question “What would Jimi Hendrix sound like if he were still alive today – after having taken a trip to Mars?”

Prince tips his hat to the master more directly with his choice of tone, as he employs Hendrix’s signature combination of fuzz and octave doubler.

The entire intro solo is masterfully played, darting around in fits and starts, and Ex. 5 is inspired by Prince’s wicked opening statement.

We return to the 1960s with another purveyor of the psychedelic movement: the San Francisco–based band Jefferson Airplane.

In the classic song “White Rabbit,” from their seminal 1967 release, Surrealistic Pillow, songwriter Grace Slick’s lyrics evoke 1960s drug culture while guitarist Jorma Kaukonen weaves sinewy lines over a brooding rhythm.

Kaukonen accomplishes this by deftly employing an exotic scale, another element of the psychedelic sound. While the song is broadly in the key of A major, the intro and verses center around a chord progression of F# to G, which is technically out of key.

Kaukonen navigates these chords using the 5th mode of harmonic minor, commonly referred to as Phrygian-dominant.

Harmonic minor (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, #7) is nearly identical to natural minor (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7), the only difference being its raised 7th scale degree

Harmonic minor (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, #7) is nearly identical to natural minor (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7), the only difference being its raised 7th scale degree. Note how this creates an unusual augmented 2nd interval (one and one half steps) between the 6th and 7th degrees.

The term “5th mode” simply means that Phrygian-dominant’s root is the 5th degree of the harmonic minor scale. This is the note that will sound like “home.”

In “White Rabbit,” Kaukonen employs F# Phrygian-dominant (F#, G, A#, B, C#, D, E), the 5th mode of B harmonic minor (B, C#, D, E, F#, G, A#). But you can take off your thinking cap and mellow out to Ex. 6, a trippy line inspired by this song.

Note the aforementioned augmented 2nd interval between the G and A# in the last bar.

Many critics consider the release of the Byrds' 1966 single “Eight Miles High” to be the dawn of the psychedelic era.

Influenced by the music of sitarist Ravi Shankar and jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, it is led by the twang of Roger McGuinn’s signature 12-string Rickenbacker electric.

The song as a whole juxtaposes droning instrumental sections with hauntingly beautiful vocal harmonies in much the same way that McGuinn’s playing ebbs and flows between sitar-like melodies and fiery bursts of single notes.

Ex. 7 is reminiscent of his alternately melodic and frenzied playing throughout the song.

Note that you can use an octaver, set to double an octave higher, to approximate the sound of McGuinn’s 12-string, as I have done here.

In 1966, along with his brother Sly, guitarist Freddie Stone co-founded the dynamic psychedelic funk ensemble Sly & the Family Stone.

The band drew inspiration from a myriad of styles – R&B, rock, church music and beyond – and Freddie’s nuanced playing was an integral part of their rhythmic foundation.

But rather than in-your-face raucousness, he preferred to pick his spots, his guitar often peeking out from inside the band to add subtle textures.

For example, in their 1968 hit single “Everyday People,” a cry for racial harmony which still resonates today, Stone interjects just a few fuzzed-out bass notes here and there. They never fully grab the spotlight, but they make an important sonic contribution nonetheless, adding a touch of psychedelia.

In 1969’s “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” the guitarist fires up his wah pedal and alternates between funky strummed 9th chords and staccato single-note phrases.

Ex. 8 is not unlike his approach throughout the song. A master of understatement, Stone could convey so much, often with just a few notes.

Spanning decades, with some original band members still going strong as Dead and Company, the Grateful Dead’s music inspired an intense devotion from their Deadhead fans, who faithfully followed the band from show to show as they crisscrossed the country.

The band’s songs, often crafted to be long jams when played live, left plenty of room for late master improviser Jerry Garcia to work his magic.

While many of the players above utilized varied and often strange tones, Garcia often chose a simple clean tone for his electric musings, allowing his colorful note choices and imaginative rhythmic sense to hypnotize audiences.

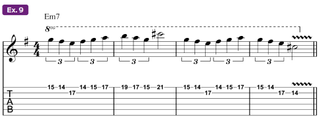

Ex. 9 is inspired by Garcia’s effortlessly fantastic playing throughout “Dark Star,” the Grateful Dead’s 1968 single, and showcases one rhythm – the quarter-note triplet – throughout the four-bar phrase, with only occasional respites.

Tension is certainly created by the sheer repetition, but more subtly, it is the way its lilting rhythm sits atop and “rubs” against the song’s straight-eighths feel that grabs our attention and keeps us hooked for the duration.

It’s the sort of magic Jerry Garcia could seemingly conjure on demand, night after night.

The 1960s psychedelic movement, spearheaded by a wave of innovative guitarists unafraid to break down traditional norms of playing and tone, directly reflected the tumultuous political and social times they inhabited.

Many more recent iconic bands, such as Red Hot Chili Peppers, Smashing Pumpkins, My Morning Jacket and the Flaming Lips, owe a debt of gratitude to the risks these players took as they created music that often seemed to be the stuff of dreamscapes.

Have a question or comment about this month’s lesson? Feel free to reach out to Jeff Jacobson on Twitter @jjmusicmentor or at jeffjacobson.net.

Jeff offers private guitar and songwriting lessons virtually.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jjmusicmentor or visit jeffjacobson.net.

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band

"This is something you could actually improvise with!" Add vibrant rhythms and sophisticated chords to your guitar playing with Jesse Cook’s five essential flamenco techniques