"When you look at his 18-page discography, the enormous impact he and his guitar have had on the world of music becomes clear." Learn these 10 techniques that made Steve Lukather a legendary studio ace

From his "Beat It" funk-rock riff to his "Rosanna" solo trick — we dissect the moves behind everyone's go-to session player

To take a flyover of Steve Lukather’s long and storied career is to essentially reminisce about the heights of the past 40 years of pop and rock music. He is both an original member of Toto — who have sold more than 40 million records worldwide, including timeless hits like “Africa” and “Rosanna” — and a prolific solo artist, with an impressive nine albums to his credit, including 2023’s Bridges. These accomplishments alone would have most of us gratefully calling it a day.

But when you look at the 18-page discography on Steve’s website — a comprehensive list of every session he’s ever done, for a veritable who’s who of iconic artists over a broad range of genres — the enormous impact he and his guitar have had on the world of music becomes clear. In this lesson, we’ll look at some of the industrious guitarist’s most celebrated classic works, starting from the very beginning.

In 1977, Luke, as he’s often called, recorded his first sessions for singer/songwriter Boz Scaggs, who hired the then 20-year-old guitarist to lay down two solos on his album Down Two Then Left. Throughout Lukather’s solo in “A Clue,” one can already hear hallmarks of his distinctive playing as he creatively combines searing melodies, modern rock licks (that still sound that way today) and a polished, sublime finger vibrato. What also stands out is the guitarist’s rare ability among rock players to deftly negotiate challenging chord changes, a skill that is more commonly found among jazz musicians. To that end, Luke was inspired by one of his guitar heroes, the session legend Larry Carlton.

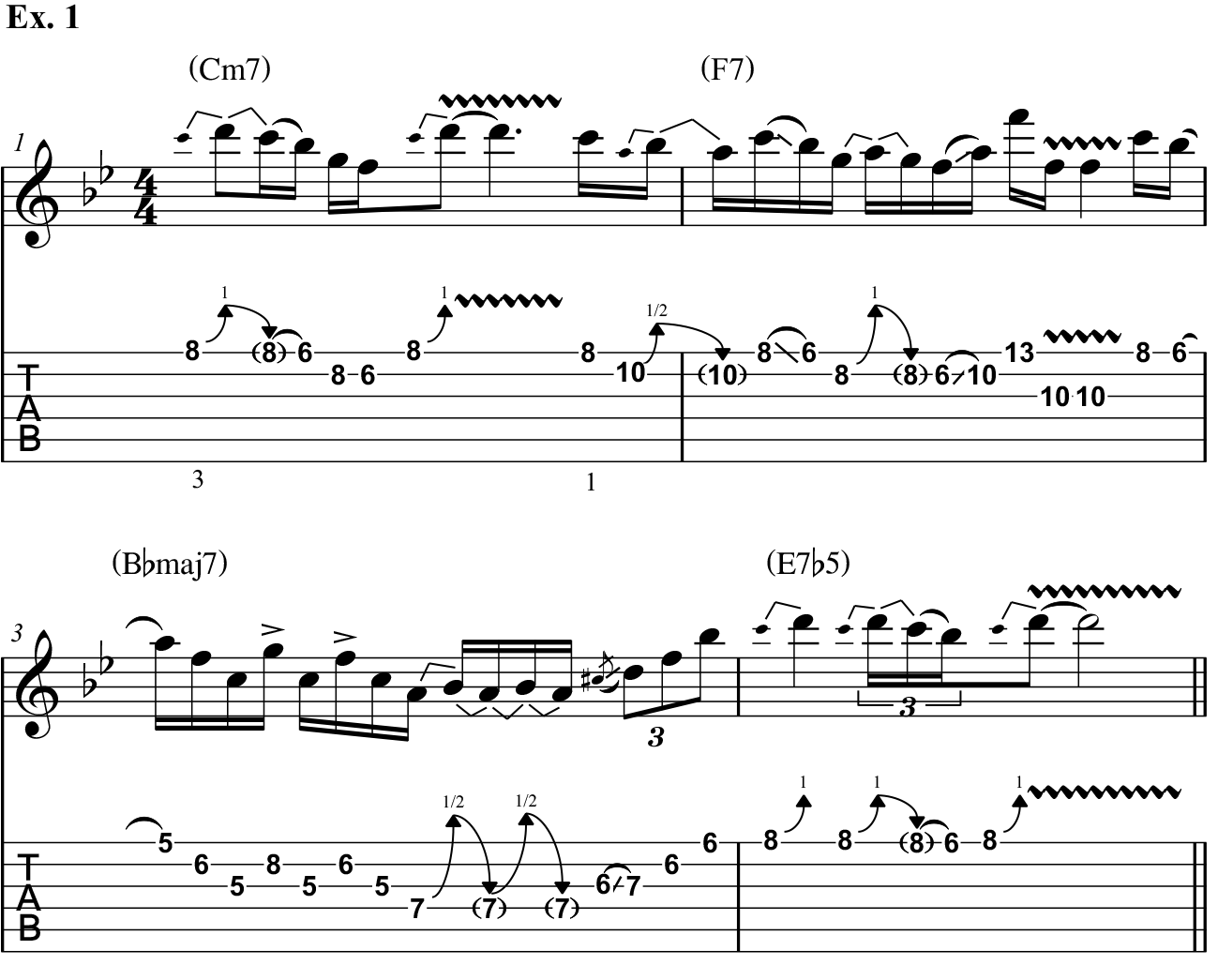

Ex. 1 brings to mind Lukather’s stirring solo in “A Clue” and reflects his well-developed melodic savvy. The entire phrase is based on the Bb major scale(Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G, A) and is used over a chord progression so ubiquitous in jazz that it has made its way to pop music: the ii - V - I (“two minor - five - one”), with the numbers corresponding to the degrees of the scale. Here that means Cm7 - F7 - Bbmaj7. Immediately, bar 1 targets a “color” tone, also referred to as an extension, a note of a chord that goes beyond the 7th. This is yet another jazz concept, and, right off the bat, we immediately target Cm7’s 9th, D. Also note bar 3’s use of an F triad (F, A, C) over the Bbmaj7 chord, which touches on the 7th (A) and 9th (C).

Lukather loves to emphasize wide intervals in his single-note lines, and, after the first note, bar 3 sets up a series of 4ths (notes two and one-half steps apart) and 5ths (three and one-half steps apart) between the F, C and G notes. Notice the accent marks above the G and F notes, indicating to pick these notes louder than normal, and how they fall on “16th-note upbeats” (between eighth notes), making us feel rhythmically off balance for a moment.

In the last bar, we encounter a chord that might cause you to wince at first, but it’s not as complex as it looks, and Lukather knows this. Ready for another jazz concept? (Last one!) The E7b5 (E, G#, Bb, D) is the tritone substitution of Bb7 (Bb, D, F, Ab), a tritone, or “augmented 4th,” being three whole steps. Briefly, these chords can be substituted for each other because they share two defining notes, their 3rd and the minor, or “flatted,” 7th. For E7b5, these key notes are G# and D, respectively. Since G# is just another way of saying “Ab,” you can see that Bb7 also shares those same two notes; the E7b5 just has a bit of a funny bass note, and jazzers love that sort of thing.

So what does Luke do? Similar to bar 4, he simply plays over it as if it’s a standard Bb chord, never venturing outside the major scale. He targets a D note, which is the 3rd of our key, Bb, and also the colorful flatted 7th of E7b5. The main takeaway here is that by treating the E7b5 as if it’s a Bb chord, Luke chooses the simplest option, knowing this will most often sound best. This is key to understanding why he has been

a first-call session player for decades.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

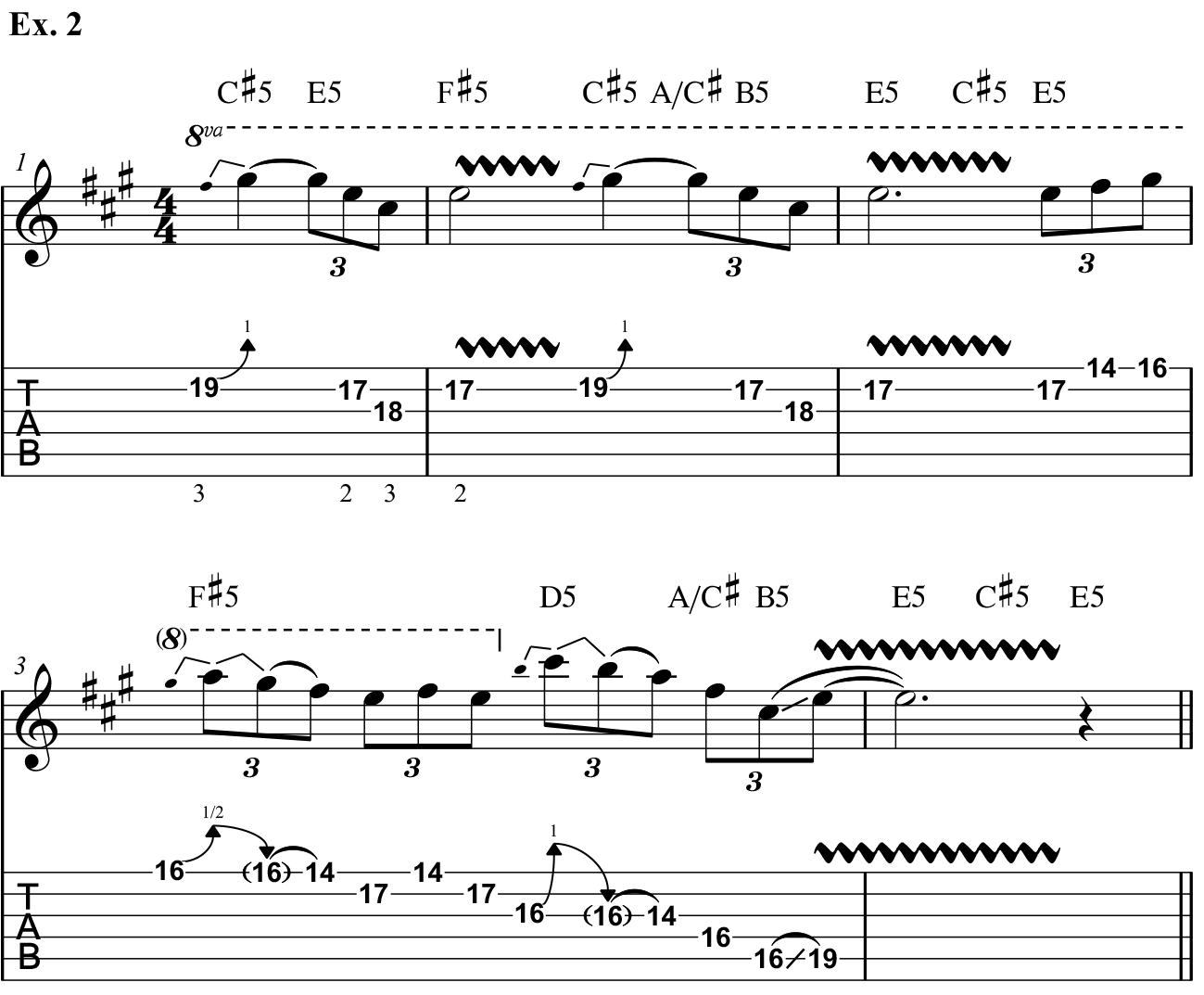

Let’s take a break from all of these sharps and flats to have some fun with vibrato. Lukather often wields his like a samurai sword, and it’s on full display in Toto’s very first single, 1978’s “Hold the Line” (from Toto). Ex. 2 is not unlike Luke’s solo — brash, aggressive and just plain nasty in the best possible way. To cop this bold attitude, your vibratos will need to be wide and even. Think of them as being like a series of bends and releases occurring in rapid succession, with the motion coming purely from your wrist. Notice in the tablature the prescribed use of the 2nd finger to fret and shake the E note on the B string’s 17th fret, which offers you better control of the vibrato instead of your 1st, giving you more leverage for pushing the string upward (toward the lower strings).

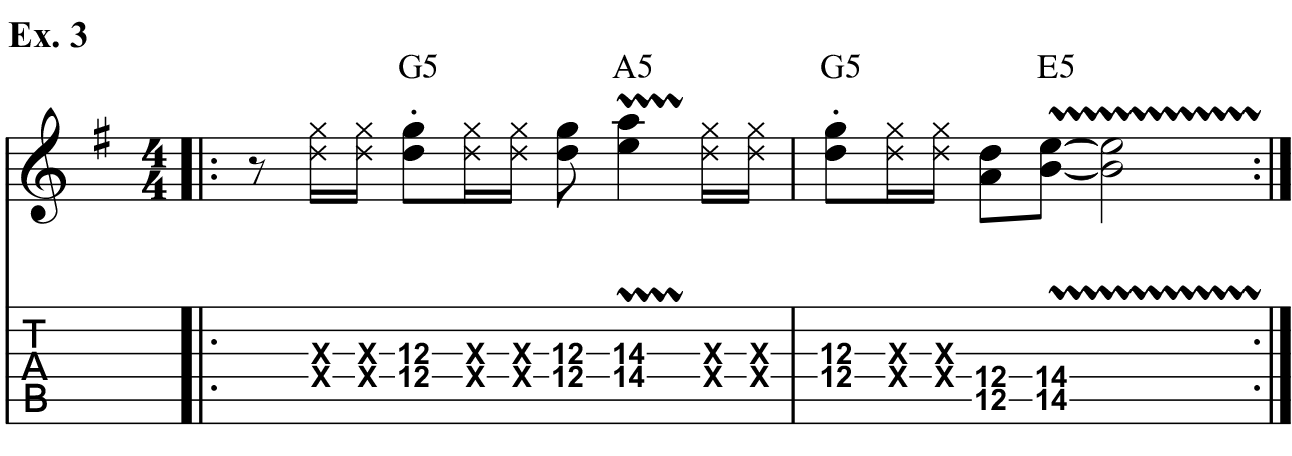

Fast-forward to 1982, when Michael Jackson is at Westlake Recording Studios in Los Angeles, working on what would become one of the most seminal albums in music history, Thriller. By request of legendary producer/arranger Quincy Jones, Lukather appears on three of the album’s songs. For “Beat It,” Eddie Van Halen rightfully gets most of the attention, due to the rock guitar icon’s master class of a solo. But Luke’s rhythm part beforehand sets up the legend’s guest appearance perfectly, creating tension that portends something special is about to happen. This sort of thing is what the best session players do every day, and without much fanfare. Ex. 3 is reminiscent of the guitarist’s killer funk-rock riff in this classic track.

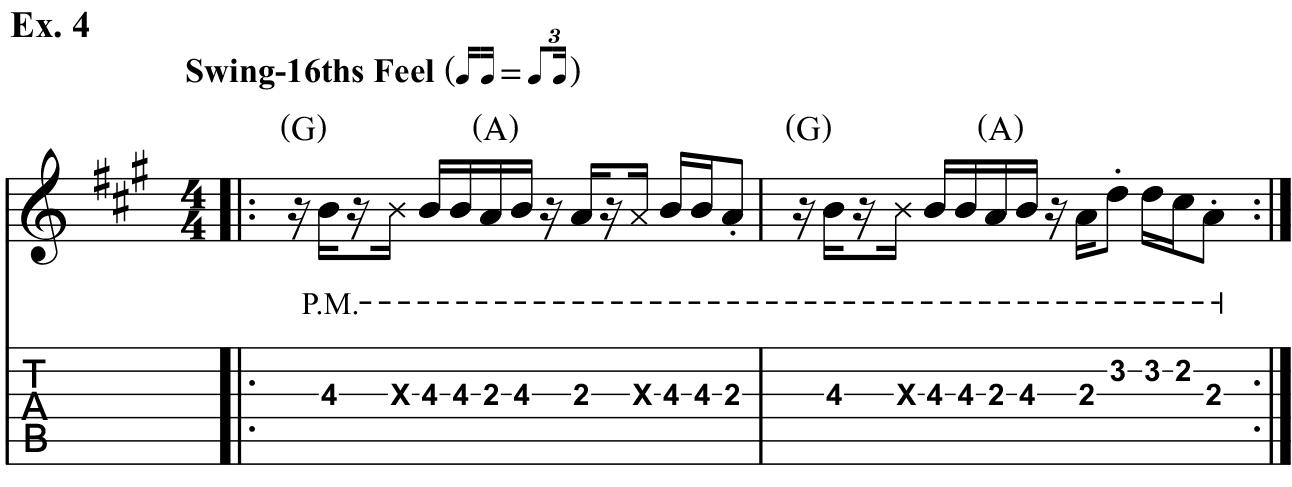

During the recording of Jackson’s “Human Nature,” Jones felt the track didn’t have the proper level of funkiness and tasked Lukather with resolving the issue. A tried-and-true move for session guitarists, and one that is often heard in classic Motown and R&B songs, is to add a “popcorn” part, consisting of stealthy, palm- and fret-hand-muted single notes that contribute a percussive, almost conga drum–like backing part that fortifies the groove with notes that “agree” with the key. Not surprisingly, Luke added just the right amount of funkiness. In fact, Jones was so taken with his parts that he gave him an arranging credit on the album, a very rare occurrence for a session player. Ex. 4 is reminiscent of the guitarist’s main part. To achieve the palm muting (“P.M.”), lightly rest your picking hand on the guitar’s bridge, resulting in a subdued attack and quick decay when notes are struck. Keep in mind that the pitchless, fret-hand-muted “dead” notes (indicated with Xs) are just as important, if not more so, to achieving the desired level of funkiness. To deaden notes, simply lift your finger so that it lightly rests on the string.

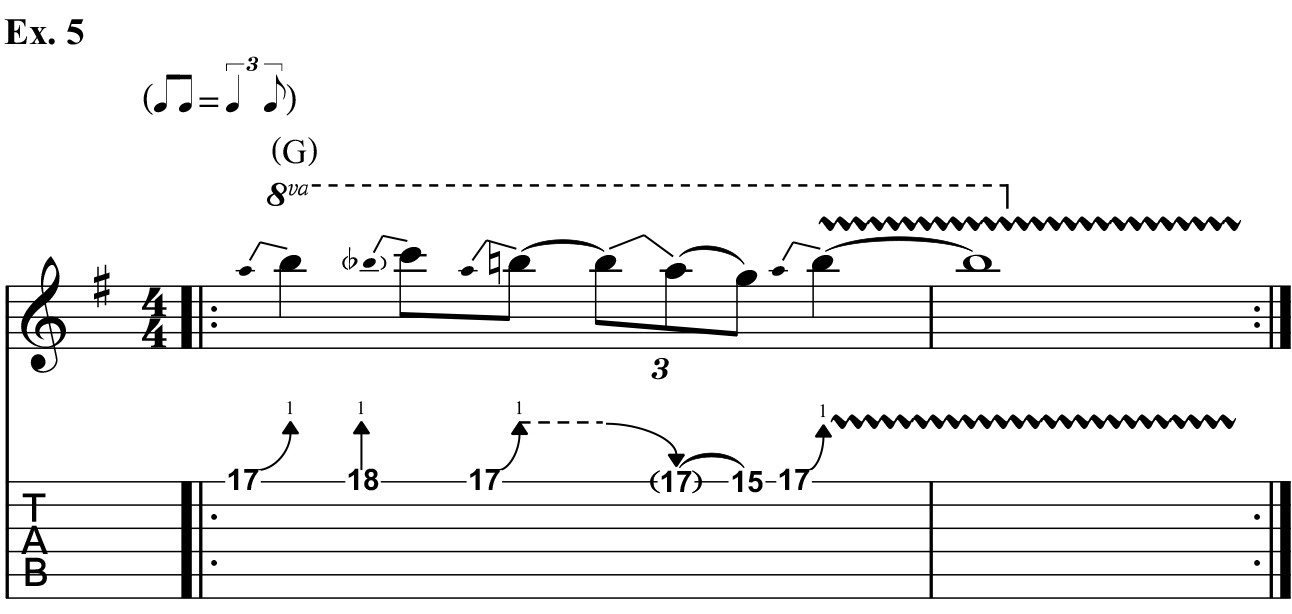

That very same year, Toto released what would become the group’s most successful album to date, Toto IV. The debut single, “Rosanna,” features Lukather playing two classic solos. He does something particularly nifty in the middle solo, along the lines of Ex. 5. After bending the initial note, continue to hold it while fretting the same string one fret higher with your pinkie. Doing this allowed Lukather to reach a note (C) that would otherwise be quite awkward to play, first having to release the bend, then reaching for it up at the 20th fret. As indicated, notes are played with a swing, or “shuffle,” feel. And be sure to nail the Luke-style wide, sexy vibrato on the last note.

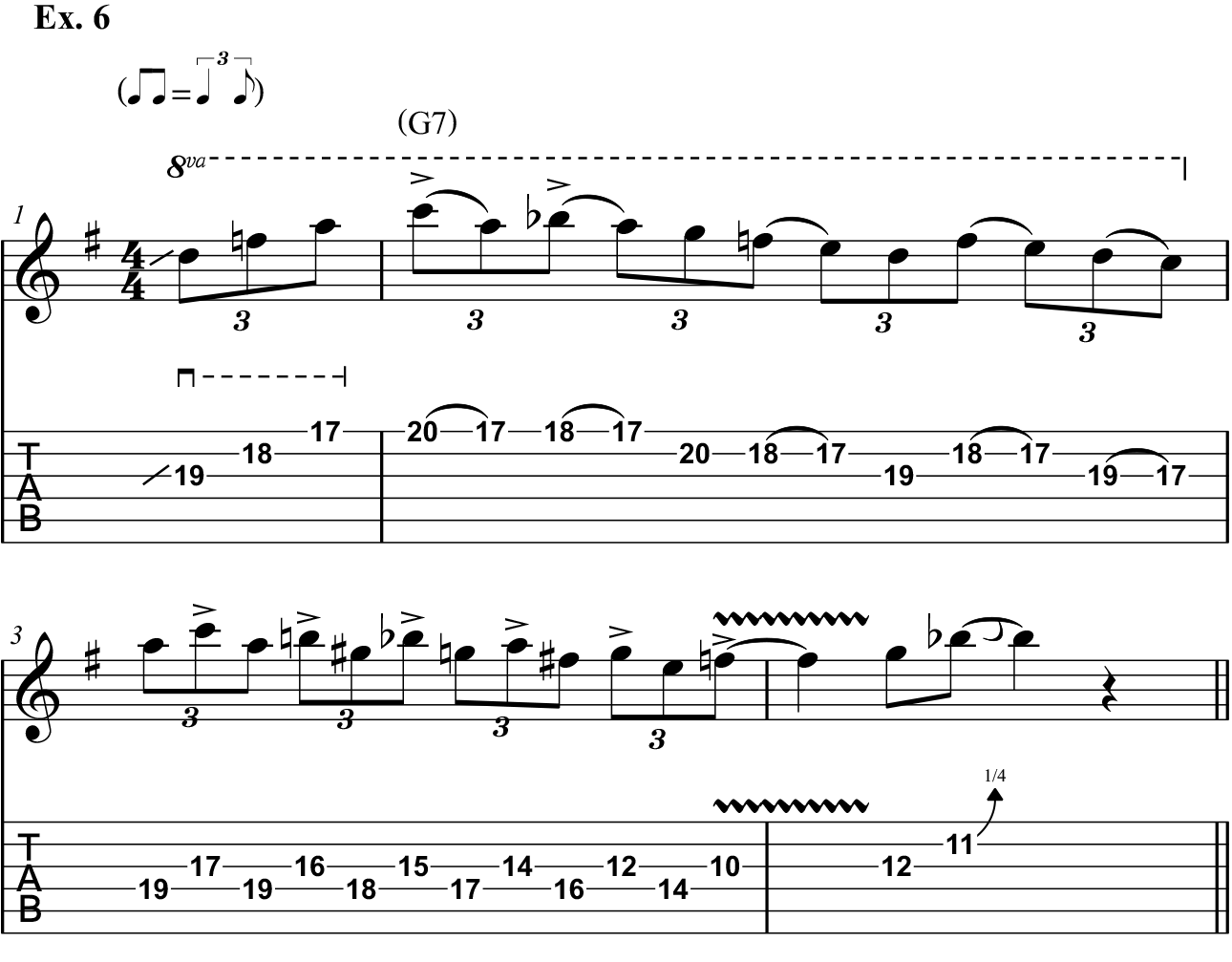

As the story goes, while recording the song, drummer Jeff Porcaro continued playing when the rest of the band expected it to have ended, resulting in a spontaneous “outro jam.” Lukather immediately hits the ground running, delivering a 54-second blistering tour de force. Ex. 6 is inspired by one of its many great moments. Over the G7 vamp, he begins by spitting blues fire then suddenly switches gears, playing a Dm7 arpeggio (D, F, A, C) which notably targets G7’s 9th (A) and 11th (C). Once again, because he’s aware of the available extensions, Luke can creatively introduce new colors to shift to a different gear. The guitarist follows the arpeggio up with a cool chromatically descending lick, which is an especially clever way to move down the fretboard. Ex. 6 brings this crafty section to mind, and, as the song fades, we’re left to wonder what sort of additional magic ended up on the cutting room floor.

Lukather clearly excels at outro solos, and in 1983, he would record another for ex-Commodore Lionel Richie’s “Running with the Night,” from Can’t Slow Down, an album that would go on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide. In the studio, Lukather was playing along while listening to the track for the very first time. When the song ended, Richie declared, to the guitarist’s surprise, that no further takes would be required; they had been recording and the solo was a keeper.

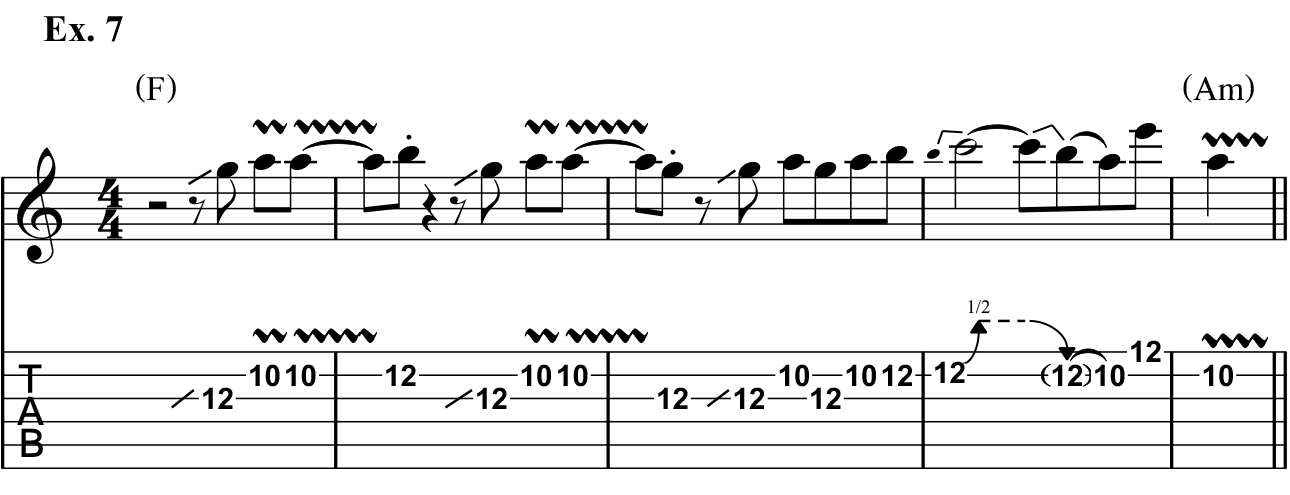

We can sense Lukather is playing quite freely here — possibly even a bit busier than he would have if he had known the red “record” light was on. His opening is a great example of the adage, “you never get a second chance to make a first impression,” as how one begins a solo might just be the most important part. Luke is about to go into beast mode, but it’s notable that he doesn’t start there. Instead, he instinctively creates a motif, which, in a musical sense, refers to melodic and/or rhythmic patterns that can be repeated. Here it involves combinations of just three notes and a robust amount of space, either in the form of rests or a long-held bend. Leaving space builds anticipation, keeping the listener guessing as to what’s coming next, and Ex. 7 is informed by the guitarist’s entrance here.

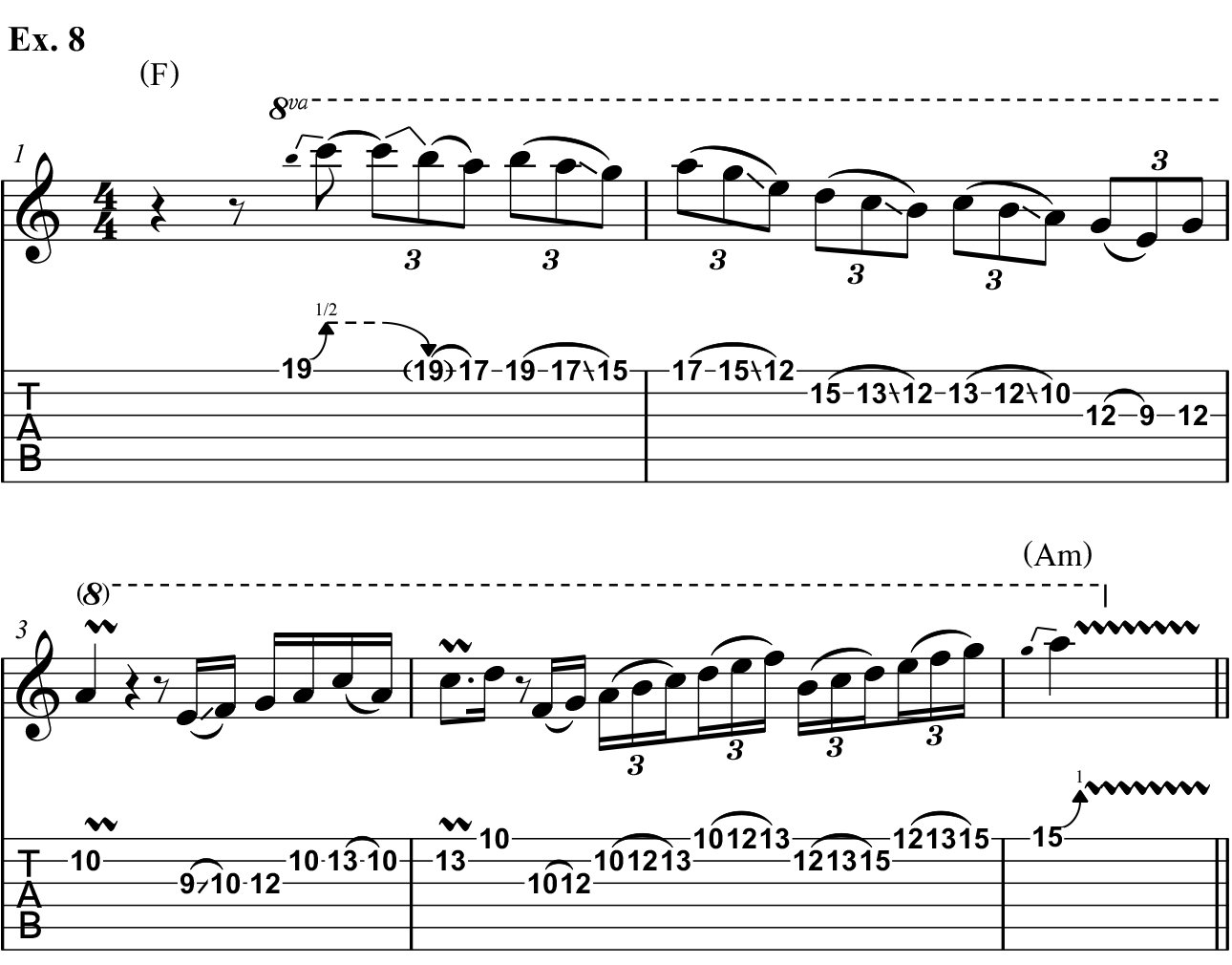

Ex. 8 brings to mind a later section where Steve again builds tension, this time with more notes, including a nod to the ’80s shred ethos.

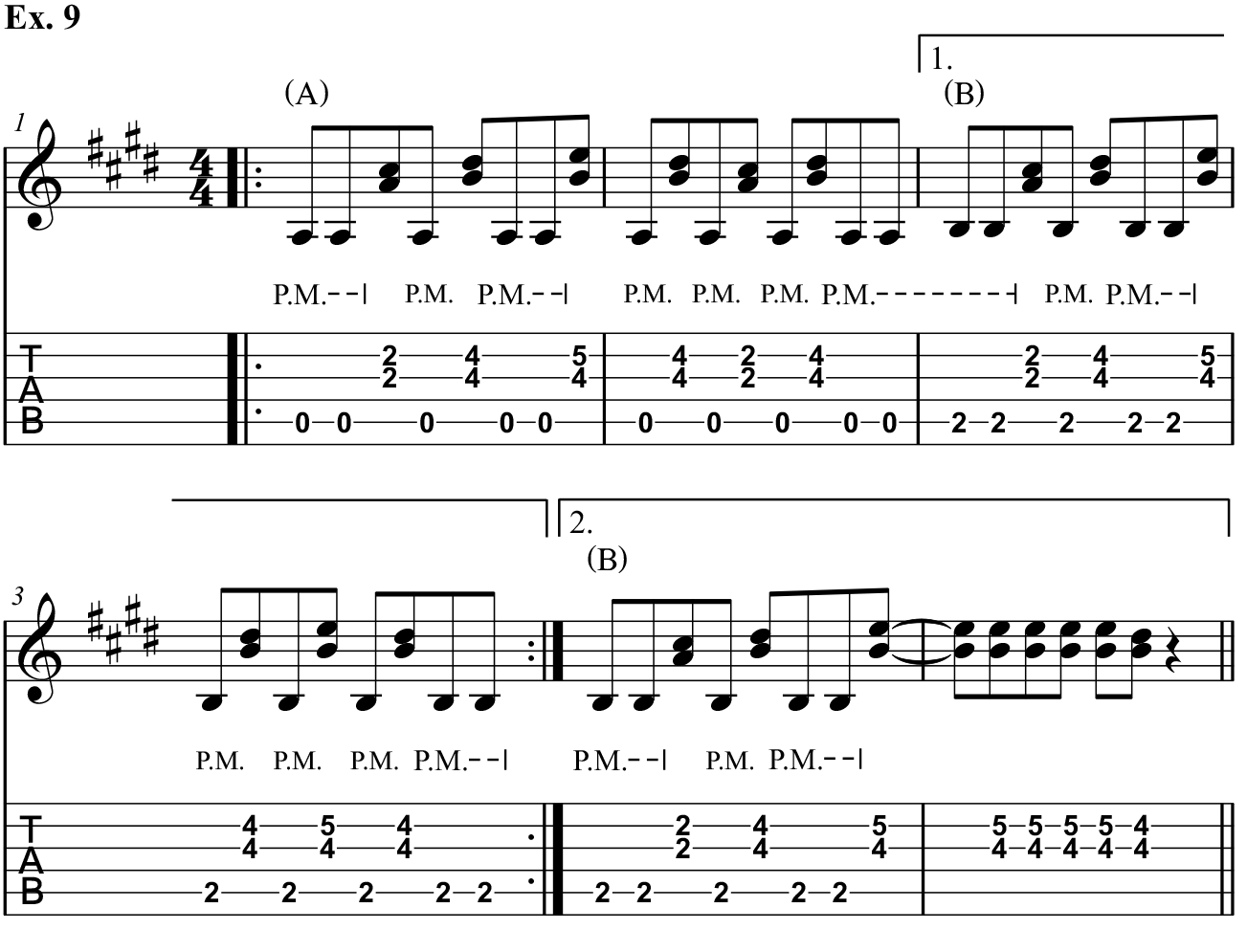

A couple of years earlier, in 1981, Lukather co-wrote and played on the Tubes’ classic track “Talk to Ya Later,” from The Completion Backward Principle. It remains a rock radio staple and is packed with great Lukather moments. Ex. 9 brings to mind his dynamic intro, and it’s challenging to keep up its blistering pace. Dyads (two-note chords) on the 2nd and 3rd strings alternate with chugging palm-muted 5th-string bass notes, requiring the 4th string to be repeatedly skipped over. Picked with

all downstrokes, it’s quite a workout.

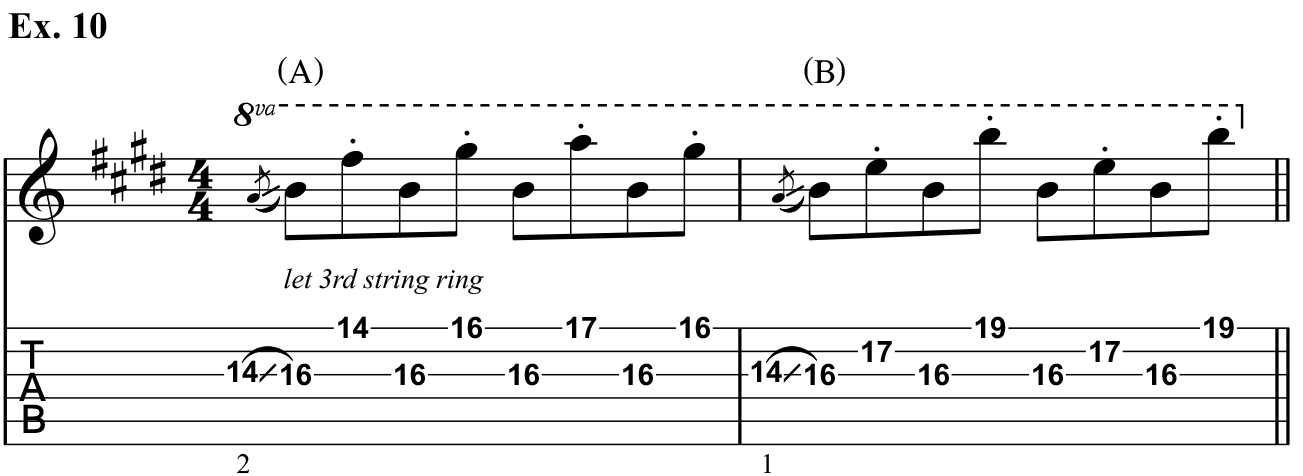

Lastly, there’s a cool pedal point lick in Lukather’s earlier solo, some-thing he does often. A pedal point is a sustaining or rearticulated note that’s generally played below or sometimes above a melodic figure or accompaniment. Ex. 10 is reminiscent of the guitarist’s ping-ponging phrase at 3:38. Played on the G string’s 16th fret, the pedal tone, B, is left to ring under the higher-pitched, staccato (short) notes with which it alternates. To keep each higher note from ringing, simply loosen your grip on the string so that it breaks contact with the fret.

Perhaps even more than his extraordinary guitar skills, it’s Steve Lukather’s uncanny aesthetic sense of what a song ultimately needs to blossom that has distinguished him for over 40 years. Whether providing subtle background parts or enduringly listenable solos, the guitarist remains an active and highly sought-after top gun in contemporary music.

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.