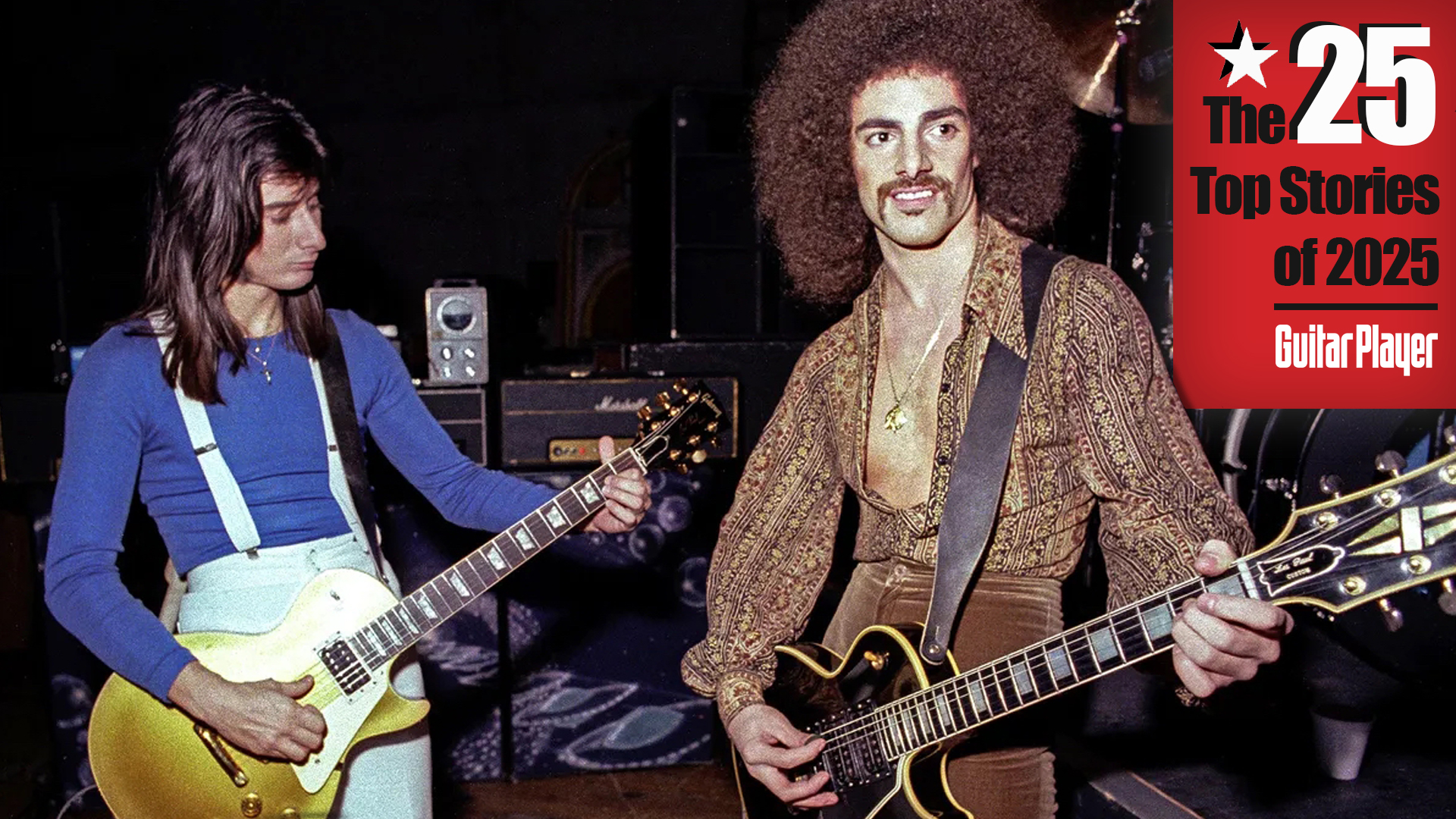

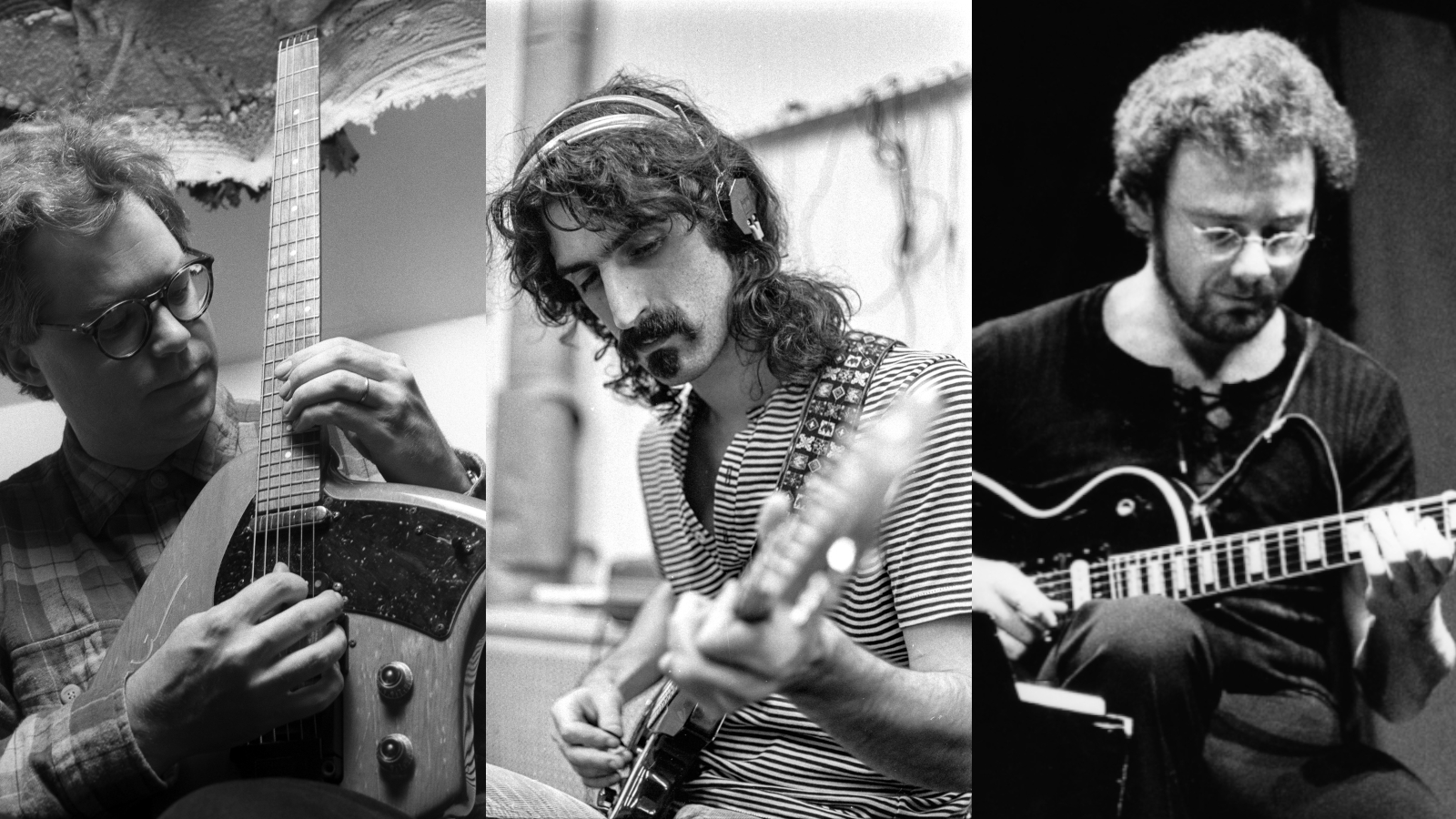

Sick of Playing the Same Old Lead Lines? Here’s How Guitar Players Like Robert Fripp, Bill Frisell and Frank Zappa Broke the Mold

Learn to play “outside” by superimposing arpeggios over chord changes

If you’re like me, you may have thought about your melodic leads and improvisations at one time or another and said, “I’m sick of playing what everyone expects to hear in my solos. Always the same scales, the same arpeggios… I need to take some chances!”

It’s easier said than done, however. So how does one take real melodic chances without sounding like your guitar is falling down a flight of stairs?

In jazz circles, this approach is referred to as “playing outside the changes,” or “playing out"

The key to achieving this seemingly elusive objective is to use harmonic-melodic substitutions, or superimpositions. This means either performing a line based on an arpeggio that differs from the chord over which you’re playing, or employing a scale that operates outside of a given key.

I touched upon this concept previously in this lesson but offered only a hint of the possibilities. Each example’s superimposed arpeggios stayed within the bounds of the original key.

But there’s nothing keeping you from superimposing arpeggios that venture outside of the given key.

In jazz circles, this approach is referred to as “playing outside the changes,” or “playing out,” for short.

This concept was pioneered back in the 1950s and ’60s by innovative jazz legends John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and others. Jazz and rock guitarists such as John Scofield, Bill Frisell, Robert Fripp, Frank Zappa, Robben Ford, Julian Lage, Mike Stern, Jim Campilongo and Wayne Krantz have also brilliantly explored this territory in their lead work.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

To players unfamiliar with the practice, playing out can be a mystifying concept, seemingly based around the prospect of playing “random” notes that have nothing to do with the original key. But, I assure you, there is nothing random about this approach.

In this lesson, I’ll walk you through some of the mad methods of harmonic-melodic superimposition, with a focus on arpeggio substitutions, first by laying out the simplest approaches and then gradually exploring more complex and harmonically sophisticated methods.

The commentary on the examples will be primarily related to music theory – why we’re playing the notes, as opposed to how they’re played – so be sure to observe all the pick-stroke and fret-hand fingering indications in the notation, which should hopefully provide all the hands-on guidance you’ll need.

Let’s dive in!

BAR-LINE SHIFTING

The simplest approach to superimposition involves what’s called “shifting the bar line.” This means playing over the original chord changes without truly superimposing any new arpeggios over them, but rather extending the arpeggio patterns that match the chords.

This is done by either anticipating the next chord – melodically implying it before the chord change – or prolonging the previous chord’s arpeggio, so that the arpeggio of the previous chord or the next lays over the current chord in the accompaniment.

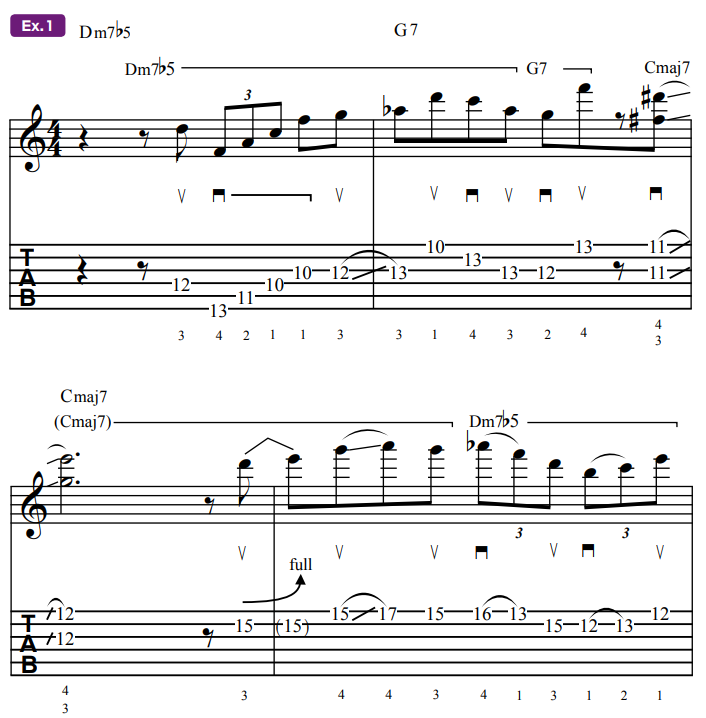

Ex. 1 presents a melodic line played over a repeating iidim-V-I progression in the key of C (Dm7b5 - G7 - Cmaj7), with each chord falling on the first beat of the bar (on “one”).

Instead of lining up each melodic arpeggio to change on beat one, along with the accompaniment, we’re either extending the arpeggio into the next chord (what’s called suspension) or starting to play the arpeggio of the next chord early, before it appears in the accompaniment (anticipation).

Although we’re not actually introducing anything different here, we’re emphasizing the tensions of each chord, meaning the scale tones that fall between the root, third, fifth and seventh, played an octave higher, which are the ninth, 11th and 13th.

For example, in bar 1 we play a Dm7b5 arpeggio (D F Ab C) over the that same chord.

In bar 2, however, we keep playing that arpeggio, prolonging it as the chord changes to G7 (G B D F) in the accompaniment.

While both chords share the notes D and F as common tones, in bar 2 you’re superimposing the notes Ab and C from Dm7b5 over G7, with those two notes now being heard over a G root note as the b9 and 11, respectively.

This melodic superimposition creates a decidedly jazzier and more dramatic G7b9(11) sound (G B D F Ab C).

As you study the remainder of this example, and all those that follow, notice that each anticipation and prolongation is indicated by a second, lower row of chord names, which identify the arpeggios played, with horizontal lines and brackets showing the extent of their duration.

THE HALF-STEP APPROACH

Here is where we start truly playing “outside,” or “out.”

When we talk about the concept of half-step approaches, we generally think about it in terms of a single tone that sits a half step above or below a chord tone and resolves to it within the course of one beat or less.

Because the resolution happens so quickly, even if the approach tone is out of key, it never truly sounds “out.” Instead, the half-step approach merely emphasizes the chord tone you’re targeting by resolving to it in short order, more like a grace-note articulation of the chord tone rather than a true disruption of the key.

To take our first steps outside of the key, we’re going to apply this approach not only to a single chord tone but to entire sequences of notes. We’ll accomplish this by playing an arpeggio that sits a half step above or below the accompanying chord, taking a chromatic approach but delaying the resolution to the “correct” key.

This allows for more notes outside of the key to sit between chord tones before resolving. By giving these outside tones some melodic structure – in this case an arpeggio instead of a single note – the eventual resolution to the accompanying chord is still perceived by the listener as if you were resolving a single note, albeit with a more interesting and jazzy approach, one that temporarily gives the listener a sense of unease that increases with each outside tone you play before finally resolving.

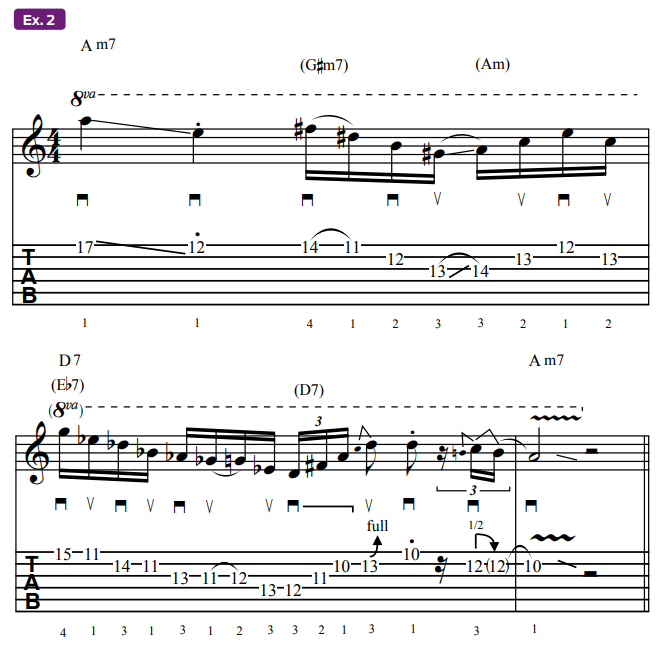

Ex. 2 demonstrates this melodic device applied to a simple two-chord progression, Am7 to D7, that’s based on the A Dorian mode (A B C D E F# G A).

Over the Am7 chord in bar 1, we superimpose a four-note G# m7 arpeggio (G# B D# F# ) on beat three, which represents a chromatic half-step shift downward from our “one” chord, then resolve it back up to Am on beat four.

Similarly, in bar 3 we superimpose an Eb7 arpeggio (Eb G Bb Db) over the underlying D7 chord (D F# A C), which represents a chromatic half-step shift upward. This move also creates dramatic tension that likewise resolves, or releases, satisfyingly on beat three, as we shift back down to the correct key and play a line built from a D7 arpeggio.

THE TRITONE SUBSTITUTION

Normally, when we think of chord substitutions we think in terms of changing the chord progression itself, or reharmonizing the accompaniment. But the same concept and approach can work effectively without altering the chord accompaniment at all, but rather by implying different changes over it melodically, via different, superimposed arpeggios.

The tritone substitution is among the most common substitutions, which also means it makes for a great superimposition as well.

Any dominant seven chord – a major triad (1 3 5) with a minor, or “flat,” seventh (b7) added – can be replaced by, or superimposed with, a dominant seven chord that sits three whole steps, or a tritone, above or below.

This works because the 3 and b7, commonly referred to in jazz harmony as the guide tones, are common to both chords, with their roles reversed – the 3 becomes the b7, relative to the new root note, and the b7 becomes the 3

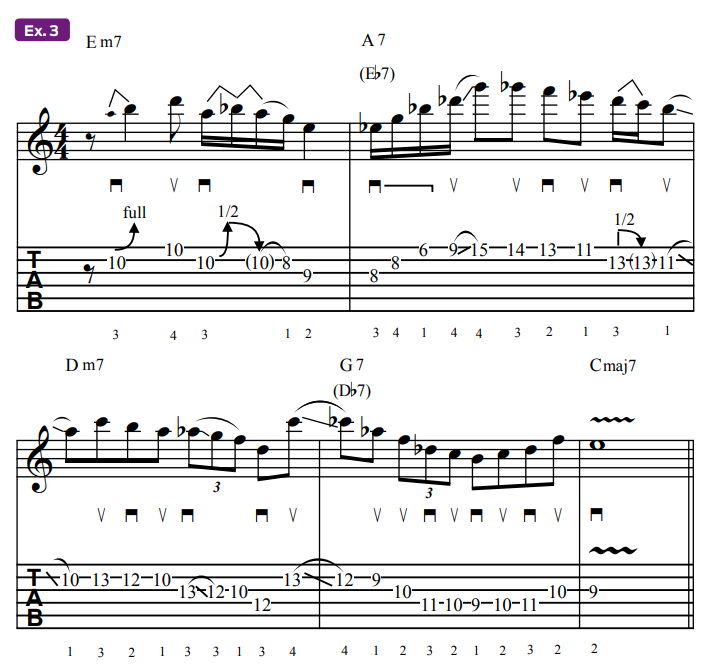

Ex. 3 presents an adventurous melodic line played over a straightforward diatonic (scale- or key-based) chord progression in the key of C: Em7 - A7 - Dm7 - G7 - Cmaj7, or iii - VI - ii - V - I. If we were to replace each dominant seven chord with a tritone substitution, it would look like this: Em7 - Eb7 - Dm7 - Db7 - Cmaj7.

Note the chromatic root motion added to this modified chord progression, compared to the original, which moves very angularly in fourths/fifths.

Instead of replacing the chords, however, our example melodically superimposes these tritone substitutions over the existing progression.

The result is a lead that veers forcefully between tension and resolution with each alternating bar, creating a musically compelling feeling of forward motion.

PIVOT TONES

Another musically cool and effective technique for superimposing arpeggios from outside the prevailing key is to take a single note from a given chord and overlay a completely different arpeggio that shares that one note, or common tone, which is often referred to as the pivot-tone substitution.

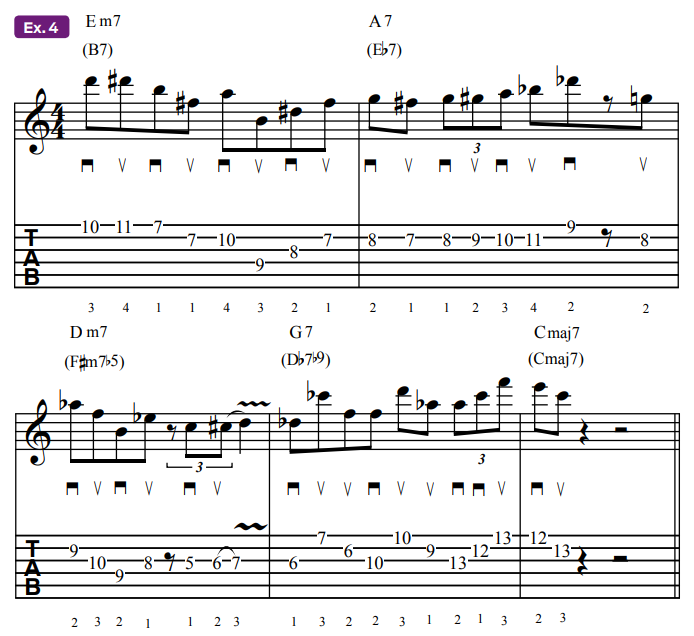

Played over the same diatonic progression as the previous example, Ex. 4 keeps the tritone superimpositions over the A7 and G7 chords (Eb7 and Db7, respectively) and adds new superimpositions from pivot tones on top of the remaining chords.

Over Em7 (E G B D) in bar 1, we use the note B as our pivot tone and superimpose a B7 arpeggio (B D# F# A).

Conversely, over the Dm7 chord, we’ll superimpose an Fm7b5 arpeggio (F Ab Cb Eb), using the shared F note as our pivot tone.

In both cases, the superimposed melodically implied chords create a significant amount of tension that is only resolved when you finally land on the pivot tone.

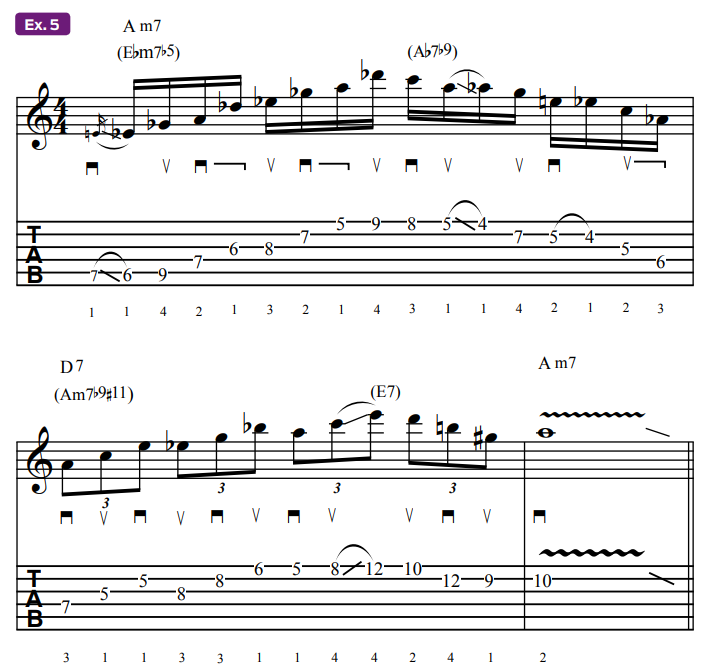

Ex. 5 takes this idea even further. Here, over the Am7 - D7 progression found in Ex. 2, we split each bar and superimpose two arpeggios over each chord.

In Bar 1, over Am7, we first superimpose Ebm7b5 (Eb Gb A Db) using the A note as our pivot tone.

Then, on beat three, we switch to an Ab7b9 (Ab C Eb G Bb), with the shared C note serving as our pivot tone.

Moving into bar 2, we superimpose Am7b9# 11 (A C E G Bb D#) over the D7 chord (D F# A C), using both A and C as pivot tones.

On beat four, we switch to an E7 arpeggio (E G# B D) before resolving back to the root of Am to finish.

When exploring this and more advanced superimposing techniques on your own, put your best foot forward by starting your lick either on the pivot tone itself or on a chord tone from the accompanying chord, and then shift into the non-pivot tones of the superimposition.

The purpose of this is to give your melodic line a solid tonal foundation to build on. The tension that comes from playing out will be far more effective if you start from a more balanced sound that an accompanying chord tone will give you.

COLTRANE CHANGES

Tenor and soprano sax legend John Coltrane, one of the most innovative musicians of the 20th century, pioneered the use of multitonic systems in jazz.

’Trane most famously utilized his three-tonic system in his iconic compositions “Giant Steps” and “Countdown.” The chord progressions to these tunes would later come to be widely known as Coltrane changes.

Instead of operating in one key, as one normally would, multitonic systems operate in either three or four equidistant keys at the same time.

In a three-tonic system, the three keys are two whole steps, or a major third, apart from one another, whereas a four-tonic system uses four keys a step and a half, or a minor third, away from one another.

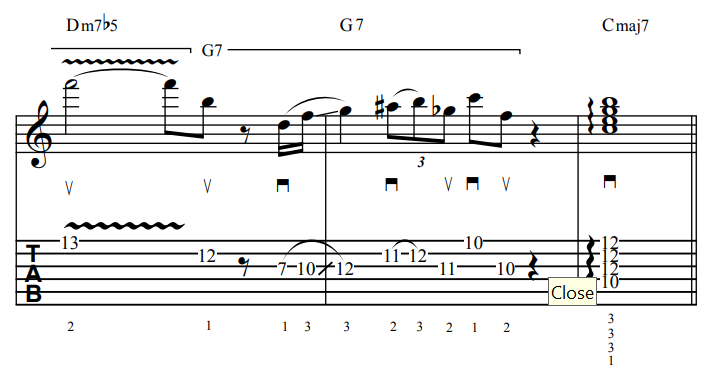

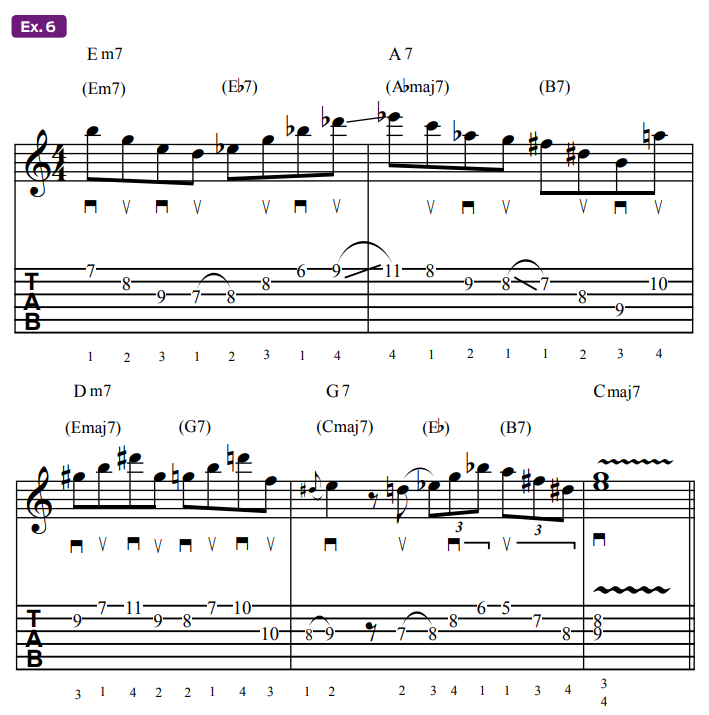

Ex. 6 takes the progression from Examples 3 and 4 and superimposes a three-tonic system over it, as implied by its arpeggio-based melody.

The parent key here is C major (C D E F G A B), while the remaining two tonics of the three-tonic system descending from C are Ab major (Ab Bb C Db Eb F G) and E major (E F# G# A B C# D# ).

After arpeggiating the accompanying chord Em7 (E G B D) in the first half of bar 1 – starting off in the key of C – we then arpeggiate Eb7 (Eb G Bb Db), which is the V7 chord of Ab.

From there we resolve the Eb7 to Abmaj7 (Ab C Eb G) and continue arpeggiating each V7 - Imaj7 cadence of the three tonics, continuing in descending order (Eb7 to Abmaj7, B7 to Emaj7, G7 to Cmaj7) with each implied Imaj7 resolving on the downbeat of the next bar.

On the last two beats of bar 4, we throw in one last Eb7 and B7 arpeggio, which are the V7 chords of the keys of Ab and E major, respectively, before ending on the original tonic chord, Cmaj7.

This creates an incredibly tense lead line that nevertheless resolves back to the original key, C.

With all of the keys being equidistant from one another, they create a sound that may be described as a whole-tone-like tonality – the whole-tone scale being a six-note scale wherein each successive note is a whole step above the previous one – only far more complex. It may take you some time to develop an ear for what works and what doesn’t.

But whether you’re looking simply to dip your toes outside the key or want to embark on your own jazz odyssey (not to be confused with the Spinal Tap song), these tools will act as a perfect roadmap for playing out with perfection.

Just remember, patience is key, and don’t be afraid to take chances when employing these techniques in your own leads. Be adventurous. Besides, what’s the use in sounding like everyone else?