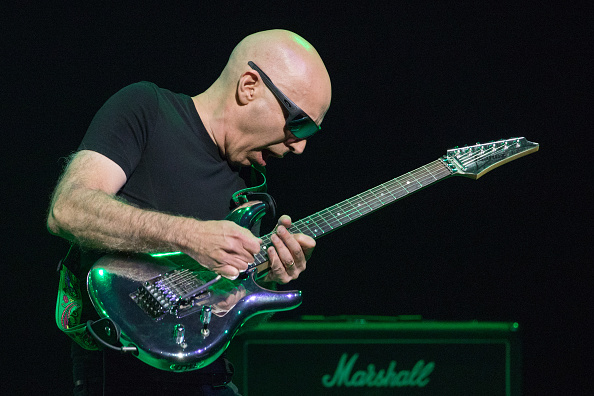

Joe Satriani is happy to discuss nearly any topic related to the guitar. But when the subject turns to tone, the voluble master of the six-string becomes downright enthusiastic. “Tone is such an endlessly fascinating concept,” he says. “Right off the bat, what I find interesting about tone is how subjective it is: What’s good tone? What’s bad? There may not be a right or wrong here, because, as it is with all music and art, context is everything.”

For Satriani, context goes hand in hand with intention. “Whenever you’re dealing with the idea of matching a guitar sound to a song, the first thing you have to ask yourself is, ‘What do I want to say with my instrument?’ You have to consider your intentions, and that becomes context. Context will ultimately define if your tone is good and proper for what you’re trying to put across.”

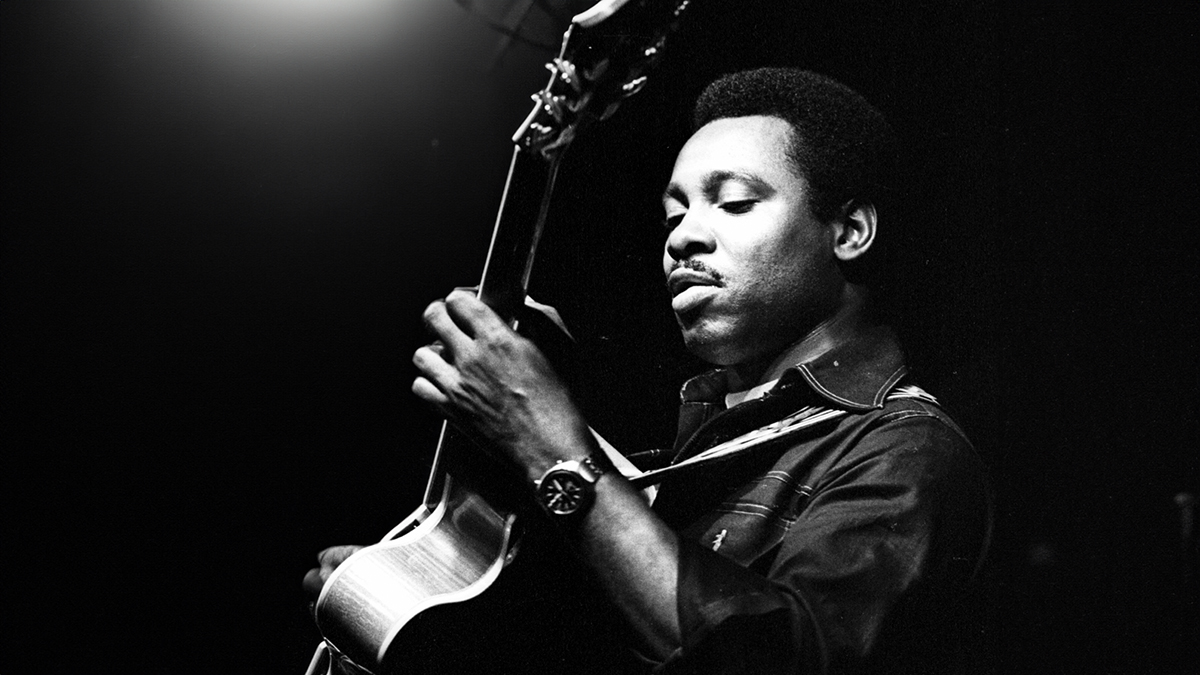

As an example, he points to “Rumble,” Link Wray’s groundbreaking 1958 instrumental. Years before The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” and The Beatles’ “I Feel Fine,” Wray’s instrumental made use of distortion and feedback. It was also one of the first popular songs built around power chords.

“All of these things are important when considering context; “Rumble” sounded like nothing anybody had ever heard before, certainly not parents,” Satriani observes. “The simplicity of the chords was perfect because it made you focus on the growling, nasty tone of the guitar. It sounded like a fight or something very sinister was taking place in a club or dance hall. Even today, it transports you to a different era and location. So, there’s context beautifully encapsulated in that incredible sound. Link Wray’s intentions came through because he knew what he wanted to put across.”

What was the first song that jumped out at you simply because of how the guitar sounded?

Before I was a player, there were things that attracted me to the electric guitar. But without the reference point of having the guitar in my hands, it was all just magic. I didn’t know anything about guitars or amps. The whole thing was a mystery to me, but I loved the way rock music sounded. Like the opening chords to The Who’s “I Can’t Explain” – to me, that was one of those magical sounds. It’s so simple, yet at the same time you wonder, ‘How did they capture that?’ It was just a series of chords that leapt out at you, and you couldn’t get out of the way. Something like that really spoke to me.

Years later, when I was playing guitar, I got a ’68 Fender Telecaster that had a Bigsby on it, and I started to go, ‘Oh, this sounds just like what I’ve been hearing on these records. It’s got that thing.’ I started to think about how I could utilize the neck pickup, and that’s when I discovered Larry DiMarzio’s pickups. Somebody told me about this guy in New York who makes humbucking pickups and how they would make your guitar sound big, but you didn’t have to worry about unwanted noise.

Getting that early generation DiMarzio pickup in the neck of my guitar really opened my ears to tone and what I could do with it. That’s the important thing about your guitar and gear: You want these tools to be like a series of open doors. You don’t want any barriers between what you’re dreaming and what you can create. You want to feel encouraged by the instrument, like it can keep pushing you in new directions. All of these little things really started for me with that ’68 Telecaster.

You want these tools to be like a series of open doors. You don’t want any barriers between what you’re dreaming and what you can create.

Joe Satriani

When purchasing a guitar, what should somebody be aware of in regard to tone?

Guitarists can always look for ways to achieve a certain sound. But the first thing you need to ask yourself is, ‘What do I want to say with my guitar?’ And the answer to that question will lead you on your way to finding the right guitar to meet that end result. When a guitar feels comfortable in your hands, it’s impossible to put it down.

There’s something about a guitar that, when it feels right, just inspires you to play. Before you know it, you’re writing songs on it and jamming on it all the time. And that’s going to affect the way you play, and it will ultimately affect your tone.

Beyond pickups, vibrato bars, amps and anything else, your hands on the guitar – the way you pick and the way you fret the strings – is the most important element of your tone. So having a guitar that really inspires you cannot be overstated.

Guitarists can always look for ways to achieve a certain sound. But the first thing you need to ask yourself is, ‘What do I want to say with my guitar?’

Joe Satriani

In terms of tone, what should somebody think about when choosing an amp?

You have to consider any purchase very carefully and make sure it fits your needs. If you need versatility, as I imagine you will, you should look for an amp that isn’t a one-trick pony. You might get a gig that calls for one type of sound, and you want to be able to dial it up without a lot of hand-wringing.

The next day, you might find yourself in a situation that calls for a completely different sound, so you want to be able to get that tone just as quickly. Years of playing cover songs and teaching guitar really drove home that point for me. You want an amp that’s flexible and dependable, one that isn’t big and complicated.

Space is an issue for a lot of people, and modern digital amps are a very credible alternative to the traditional amp with a cabinet, tubes, a transformer and some speakers. For instance, there’s the [Fractal Audio] Axe-Fx [preamp and effect processor], which is small and easy to use, and you can just plug it into the P.A. There are plenty of people who are doing that today, and they’re very happy with a digital amp because it fits with what they’re trying to do.

Where do you stand on pedal effects versus something like the Axe-Fx?

To me, it’s not an either/or situation. Pedals are moveable, so you can stack them however you want. Do you delay the reverb or reverb the delay? All of this is possible with any rack effect, too. Right now, in my studio I’m looking at a Big Bad Wah, a Whammy Pedal, a Shanks germanium distortion pedal and a little tuner going into my Marshall JVM. And I might think, ‘Oh, I should just see what it sounds like if I put the distortion before the Whammy Pedal.’ So, it’s a bit more crude, but it’s also more playful, and it doesn’t take as much time, I suppose.

The Axe-Fx is good at rearranging all your effects any way you want, but it’s a little bit time consuming. You’re dealing with a computer, basically, so you’re typing and using a mouse or a pad. It’s a lot different when you’re staring at a bunch of pedals on the ground.

All of that aside, it’s really about the sound, isn’t it? On my last couple of tours, I wound up using the Axe-Fx in the simplest way to handle delays and reverbs. And I found that the biggest benefit from it was that it passed the signal better than any other device handling those same effects in the loop. My guitar sounded like there was nothing in the effect loop. So that’s the quality of the processing, or I should say the quality of the unit itself. It’s almost entirely transparent. It’s in your system, but you don’t really hear it.

All my favorite live recordings of crazy guitar players were always in mono. It’s just so simple and raw, but it’s all there.

Joe Satriani

Unless I’m mistaken, you never went in for the big Bradshaw rigs back in the day.

I never did, no. There were a couple of things that I didn’t like about those rigs. For example, I didn’t like the way that the signal was being handled. It just didn’t sound natural enough to me; I always detected some weird phasing going on. Any of my attempts to go stereo onstage always met with phasing issues for TV broadcasts, or even in the venue. You had no idea how things were being handled. And all my favorite live recordings of crazy guitar players were always in mono. It’s just so simple and raw, but it’s all there. There’s no strange audio conflict going on.

I also noticed that, with a couple of pedals going into a loud clean amp, I had fewer issues than my contemporaries who had beautiful systems that were like works of art. Those things would break down every other night, and they cost a lot of money to build and maintain. The performers had to ship them around the world, and that was a big expense, and they had to have two of them in case one broke down. It all seemed very problematic and unwieldy.

Digital recording gets a bad rap. The fact is, there are more bad analog recordings than digital ones.

Joe Satriani

Most people can now make pretty sophisticated recordings on their computers. Any tips for getting good guitar tones at home?

You know, digital recording gets a bad rap. The fact is, there are more bad analog recordings than digital ones. That could simply be because of age. Wait a few more decades and there might be as many horrible digital recordings. Who knows?

But if we’re talking digital, one key thing is to make sure that you can record a really clean direct sound. If you can get a nice uncompressed, unequalized D.I. [direct] signal of your guitar performance, the sound can be reconfigured with plug-ins or re-amped into one of your other amplifiers. Re-amping is something I do all the time, and it started when John Cuniberti invented the Reamp box. Again, you want something that’s pure and authentic, without clipping or coloring, and that will offer you a lot of flexibility.

But remember, context is everything. It’s like I was saying about “Rumble”: it sounds like you’ve gone to a dance hall and there’s a band playing. But that’s not the image you’re trying to create if you’re recording modern progressive instrumental music. In every instance, intention dictates context.

People rarely talk about guitar cables when discussing tone, but it’s really one of the most important aspects of how a guitar sounds, isn’t it?

It really is, and it never gets the kind of attention it should. I always went for the cables that colored the sound the least. You can A/B cables to find the one that’s louder and offers more fidelity – more low- and high-end. With bad cables, we’re really talking about capacitance: The guitar signal is coming out of your guitar, and when it hits the cable, you don’t want any frequencies to be chopped off or deteriorate. With rare exceptions, shorter cables do the trick because the signal doesn’t have to travel as far, so there isn’t the same amount of frequency loss. You can test this easily: Go get a Telecaster and a Vibrolux. Take a two-foot cable, a three-foot cable and one that’s 40 feet long. You’ll be able to tell which cable works best pretty quickly.

When we were recording [1987’s] Surfing with the Alien, we got on this crazy kick of using the shortest cable possible. We even made our own Mogami cables. We were really into it. John Cuniberti would find a cable that allowed me to stand where I needed to in order to record a particular part. But that was just it: I had to stand in one spot, and I couldn’t move any further. Sometimes it was a four-foot cable, and I would stand right in the control room. It was a little crazy, but it worked.

These days, we use D’Addario cables both in the studio and on tour. We make them up for every gig. If it’s an unusual venue – if it’s a bigger or smaller place than what I’m used to – my tech, Mike, will come to me and say, “Hey, I switched to this length cable because I can save you 10 feet.” We know it’ll make a difference in how my guitar sounds.

Cheaper isn’t always the way to go when purchasing something like guitar cables.

Joe Satriani

It’s kind of funny: back in my lean years, I always went for the cheaper stuff, because economy was extremely important and I had to prioritize. I would look at my budget and say, “Well, I really want that one pedal, so I can save a few bucks if I buy the cheaper cable.” But cheaper isn’t always the way to go when purchasing something like guitar cables. This just goes back to what I said before: You want your gear to inspire you. It has to deliver a sound that makes you want to play and create.

So, if you have to spend a few more bucks on a cable, do it. And if you’re thinking, ‘Well, I can’t jump into the audience with an eight-foot cable so I should get the 40-foot one,’ just remember that the longer cable is going to affect your sound a lot more. Bigger isn’t always better. And longer isn’t either. [laughs]

Buy the Joe Satriani classic Surfing with the Alien here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band