Making the Jump: How to Master the Art of String Skipping

Nail this essential guitar technique with accuracy and ease.

It has been said that the most efficient means of getting from point A to point B is to travel in a straight line. Most guitar players cling tenaciously to this way of thinking when crafting leads, opting to move through scales and arpeggios in a linear or straight-line fashion. This limits us to just two forms of movement: stepwise motion — moving from one scale tone to the next available one above or below it on the same string — or jumping to other close scale tones available on an adjacent string, usually two, three or four scale steps away from our starting note. While this can be an effective and useful approach to making melody on the guitar, it can also be creatively stifling. After all, if you limit yourself to moving in certain relatively narrow intervals, you’re bound to repeat yourself often.

One way to break free of these limitations and expand your range of melodic options is to employ the technique of string skipping, or jumping from one string to a nonadjacent one. This gives you the freedom to incorporate wider intervals into your melodic vocabulary, such as sixths, sevenths, octaves and beyond. String skipping also allows you to play lines that are more characteristic of different instruments, conjuring melodic ideas that can be found, for example, in a Bach violin prelude or a John Coltrane tenor sax solo.

But like all new techniques, learning and applying string skipping is easier said than done, as it requires pinpoint accuracy in both your fretting and picking technique. In this lesson, I’ll teach you how to string skip efficiently and apply the technique musically. Let’s begin by breaking down the basic mechanics of skipping strings.

BASIC FLATPICKING

Proper flatpicking technique (using a plectrum) is essential for smooth string skipping, and yet it’s often one of the most overlooked and neglected aspects of one’s technical development and practice routine. So before we jump into string skipping, I’m going to break down what I find to be the most effective approach to picking, so that you can tackle these exercises from the best possible angle.

First and foremost, you need to stay relaxed. Attempting to play the guitar with any level of tension in your hands will prevent you from playing with any fluidity, as it’s like stepping on your car’s accelerator and brake pedals at the same time. Hold the pick firmly between your thumb and index (or middle) finger, making sure the point of the pick is aimed straight down toward the strings. Angle the pick slightly — no more than 45 degrees from the string — so that you’re striking it with the slanted edge of the pick, rather than the flat side. If you use the flat side, you’ll encounter added resistance from the string, requiring more energy and effort to drag the pick across it to strike a note and get ready to pick the next one. Picking with the slanted edge of the plectrum allows the string to glide down the edge of it with minimal resistance, allowing you to “slice” across the string with less effort. Not only is this approach far more efficient than the alternative, it will also do wonders for your tone.

Gently rest either the side of your palm or the butt of your wrist, whichever is more comfortable, along the bridge, just behind where the strings meet the bridge. This will anchor your pick hand, giving you a pivot point to work from and restricting the amount of movement between pick strokes. More importantly, it will also give you a more precise feel for where each string lays in relation to the others and will therefore set you up to perform string skips most efficiently and precisely, resulting in a cleaner picking technique overall.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

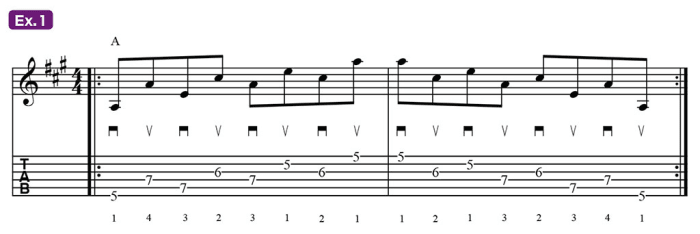

Ex. 1 is a simple exercise based on an A major arpeggio (A C# E) in fifth position. When ascending, the string-skipping pattern is “up two strings, down one, up two, down one,” etc. In bar 2, the pattern reverses: “down two strings, up one, down two, up one,” etc. This exercise will help establish the pick-hand mechanics of string skipping. Focus on making sure your pick skips each string in the cleanest manner possible, always clearing the string you’re skipping over as if jumping over a hurdle. But you needn’t “leap” any higher than necessary to clear the string, as that represents unnecessary movement and wasted energy. Be sure to focus on skipping efficiently between nonadjacent strings so that you can build a sense of dimension between one nonadjacent string and another.

Regarding the fretting hand, make sure each transition from note to note is smooth. Simply loosen your grip on the first note rather than removing your finger entirely from the string, to ensure that neither the previous note nor its open string rings out when you go to play the next note. All of this will come in handy as we progress through this lesson.

SKIPPING THROUGH THE MAJOR SCALE

As stated earlier, one of the benefits of string skipping is the ability to incorporate wider intervals into your vocabulary, which you can use to break up linear melodic patterns or generate new and more angular and interesting patterns. Ex. 2 demonstrates the latter concept by skipping through two octaves of the A major scale (A B C# D E F# G# A) in sixths. This entails playing the root, then jumping straight to the sixth note of the scale, then repeating this action sequentially through the rest of the scale, from the second, then the third and so forth. Most scalar exercises are played using different linear note groupings, such as ascending sequentially in three-or four-note groups, or in smaller intervals, such as thirds. While playing a scale in sixths can be strikingly similar to playing it in thirds, string skipping makes all the difference in terms of the pick movement and angularity of the line’s contour, with taller melodic “peaks.” Sixths are also perfectly interchangeable with thirds because they are essentially the same thing, inverted. This means that when you have two notes that make up a third, such as C and E, then bring the lower note up an octave, those notes then form a sixth (E and C, in this case). We’ll explore this further when we look at open triad voicings.

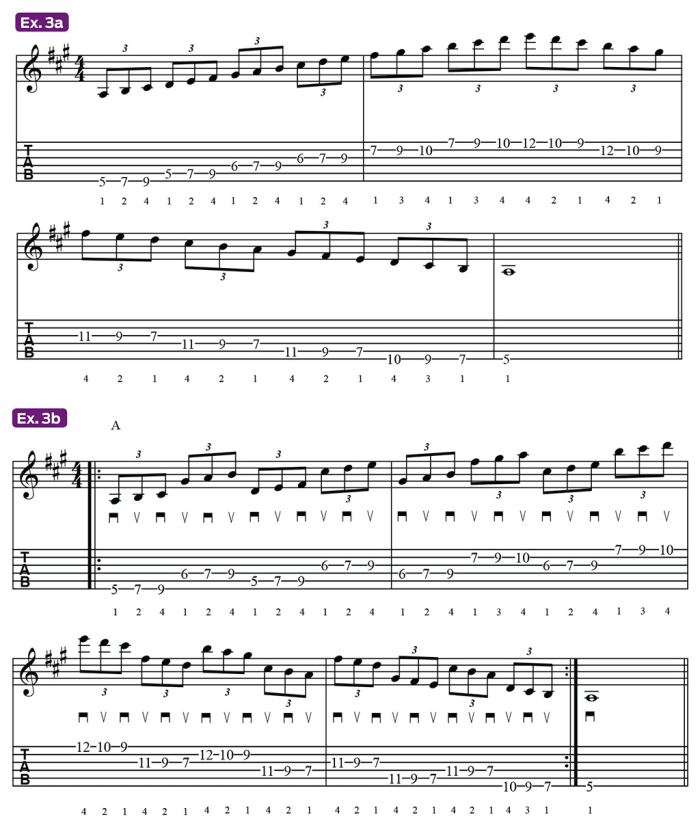

Our next two examples demonstrate one way of mixing string-skipping mechanics with linear melodic ideas. Instead of staying in a fixed position, or “box,” we’ll be traveling diagonally up and across the fretboard, playing three notes per string, an approach favored by great lead players like Joe Satriani and Guthrie Govan. Ex. 3a does this with the A major scale. When we get to the D note on the high E string’s 10th fret, we shift up two frets to grab the higher E note with the pinkie, then descend a different, higher path back to the low E string, again using three notes per string.

Ex. 3b takes this same pattern and breaks it up using string skipping. We start by playing the first three notes on the sixth string, skip over to play the four notes on the fourth string, then go back to play the notes on the fifth string, followed by those on the third string and so forth. When we get to the high D note, we shift up to E again, as in Ex. 3a, and descend through the scale with the same kind of “jump two, back one” string-skipping pattern, which creates a sort of conversational point-counterpoint, or call-and-response style of phrasing.

Repeat this exercise slowly at first and with a metronome to ensure rhythmic and technical accuracy. Focus on the efficiency of your finger movements from string to string. When your fingers are not engaged, they should be hovering just over the fretboard, relaxed and ready to deploy. If your fingers are moving around too much when navigating from one note or string to another, you not only leave more room for error but also expend valuable energy unnecessarily, making your fingers tired and tense.

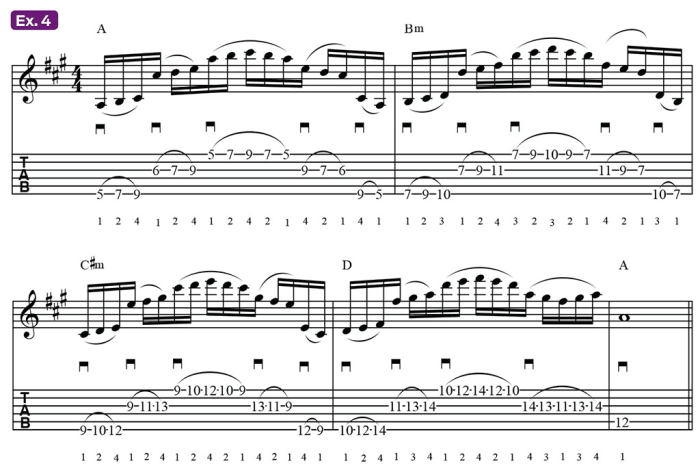

Ex. 4 follows a similar melodic template but with a larger skip, from the sixth string to the third, beautifully framing a series of diatonic chords in the key of A major with add2s or add9s. The pattern then moves over to the first string, then back down across the third and sixth strings. Upon returning to the sixth string, you will play only two notes, C# and A, then shift up to the seventh position and do the same thing with Bm. The sequence continues up the neck with C#m and D. For a varied articulation, you can employ legato phrasing, as indicated by the slurs, picking only the first note on each string and using every available hammer-on and pull-off opportunity. This is a great exercise for honing your legato technique and “fretboard traction.” Strive to make all the notes equal in volume.

SPREAD VOICINGS

Another great application of string skipping is to use it to play arpeggios with open, or “spread,” voicings. This technique, famously employed by Eric Johnson and Steve Morse, involves taking a chord that’s normally voiced in stacked thirds, such as a major triad (1 3 5), and raising, or displacing, the middle note up an octave, so that it becomes the top note (1 5 3). Doing this creates wider intervals and more space between the notes of the arpeggio while maintaining its musical integrity and making it sound bigger and grander.

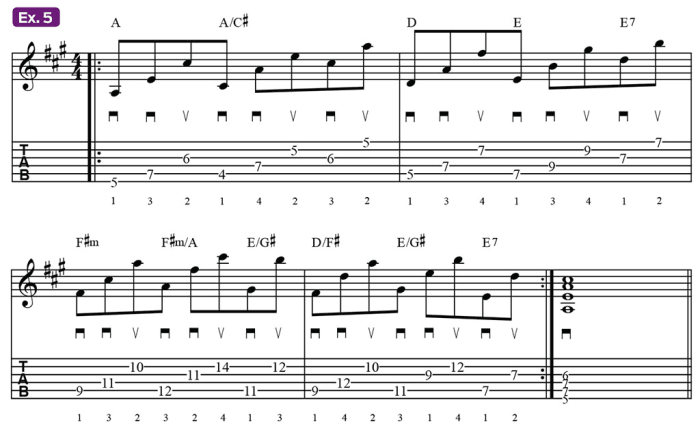

You can apply this method to any inversion of a chord, as well, as demonstrated in Ex. 5, which follows a series of triadic spread voicings in the key of A major, switching between root-position and first-inversion shapes. Each spread voicing features two tones on adjacent strings and one on a nonadjacent string. The picking technique used in this example is a form of crosspicking called a “forward roll.” As opposed to strict alternate picking, the forward roll is a down-down-up pattern perfectly suited to ascending three-note arpeggios, played one note per string. This twist here, of course, is the skipped string in each arpeggio. Each measure features two arpeggios followed by two extra alternately picked notes to fill out the bar, so the picking pattern for each measure is “down down up, down down up, down up.”

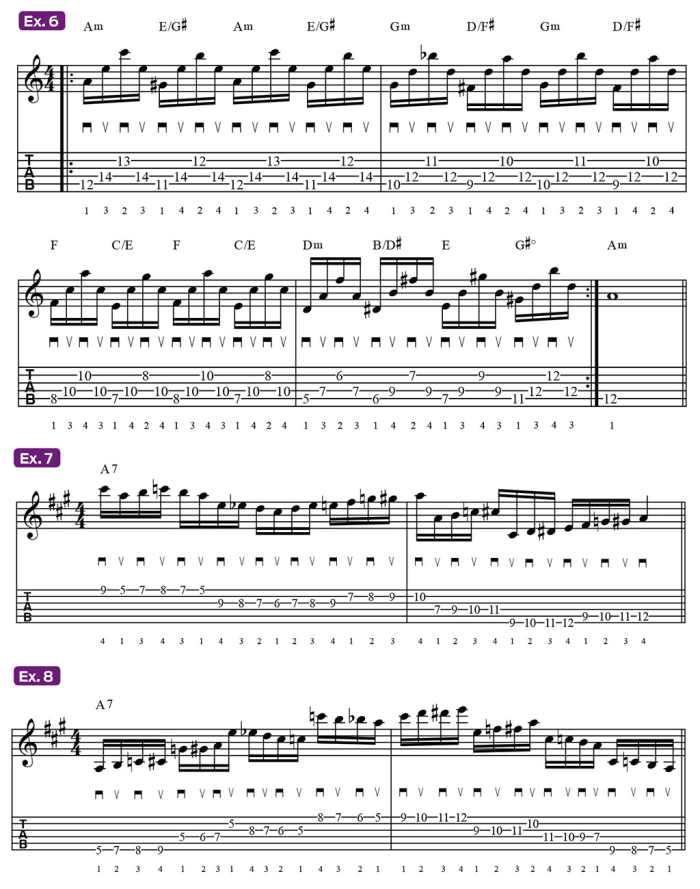

Inspired by Morse’s brilliant writing and playing on Deep Purple’s “The Well-Dressed Guitar,” Ex. 6 demonstrates spread voicings in a descending minor key context. In bars 1–3, we alternate between two spread triad arpeggios, gradually descending the neck with each measure. In bar 4, we transition back up the neck and repeat the entire four-bar progression. This musical exercise shows some of the ways spread triads, much like standard triad voicings, can be used both diatonically and chromatically to create an elegant-sounding, baroque-style stand-alone melody that clearly outlines chord changes on its own.

BLUEGRASS STYLE STRING SKIPPING

One of my favorite ways of incorporating string skipping into my playing is through bluegrass-inspired chord framing. This involves taking an arpeggio and framing it by filling in the gaps between the notes using scale tones and chromatic nonscale tones, then breaking everything up by jumping to nonadjacent strings and continuing on without breaking stride, in terms of rhythmic phrasing. The effect is reminiscent of a mandolin or fiddle solo because of the sudden wide intervals between chromatic phrases.

Examples 7 and 8 are both centered around an A7 chord (A C# E G) and use scale tones from A Mixolydian (A B C# D E F# G A), as well as chromatic passing tones to frame the chord with an angular but flowing melodic contour. Both exercises require strict alternate picking and lots of position shifting, so be extra mindful of every pick stroke movement up and down the fretboard.

By now, you should be well acquainted with the mechanics of string skipping, but this is only the beginning. Use these examples and concepts as creative templates and springboards for crafting your own fresh licks, patterns and runs.