Joe Satriani: 10 Things You Gotta Do to Play Like the Shred Legend

10 ways to play like Joe Satriani.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Although he released roughly one album per year over the past 23 years, Joe Satriani’s 1987 blockbuster Surfing with the Alien—reissued in August, 2007, as a remastered and expanded anniversary edition—remains the ultimate primer for anyone interested in copping some of Satch’s trend-setting musical mojo. I had the honor of transcribing the entire album (with the exception of “Satch Boogie”) that same year, so naturally that’s the one I’m gonna zone in on!

Satriani’s soulful virtuoso playing, incredibly cool tunes, and licensed Silver Surfer cover art culminated in Surfing’s perfect package, which forced open the elusive crack in time that seems to occur every dozen years or so when guitar instrumentals once again achieve popularity. The certified Platinum album, which followed on the heels of Satriani’s 1986 full-length debut, Not of This Earth, quickly rose to number 29 on Billboard’s Top 200 Albums chart and spawned three hit singles.

Since then, Satriani has recorded a slew of solo albums, founded the G3 guitar virtuosos tour, composed music for NASCAR, and joined Chickenfoot with Sammy Hagar, Michael Anthony and Chad Smith.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. If you want to play like Satch, first, you’ve gotta...

1. Teach

Whoever coined the phrase “those who can’t do, teach” obviously never ran into anyone like Joe Satriani, a doer, teacher, and New Yorker of the highest order. It’s well known that Satriani— who studied with jazz pianist Lennie Tristano and remains an avid Hendrix disciple—counts Steve Vai, Kirk Hammett, Larry LaLonde, and Charlie Hunter among his roster of former pupils, but he equally inspired and enlightened dozens of students who never achieved that degree of success, and I’m betting that, like any good teacher, Satch benefited as much from the experience as every one of his pupils did.

“It doesn’t matter if your student is Kirk Hammett or an eight-year-old kid with an action figure sitting on the amp—teaching makes you get your shit together,” Satriani told GP’s Darrin Fox in 2007. “As a teacher, your job is to—using the fewest possible words, and with the most musical economy you can muster—give the student what they need to move forward. You learn to be succinct, and to put forth ideas without alienating the student. You also learn to remove any of your stylistic tendencies or qualities from the information so as not to adversely affect them.” Teachers take note. Now, dig deep, and...

2. Push your gear (and your credit card) to its limits

Over the past two decades, Satriani’s physical “engines of creation” have evolved from a few basic guitars, amps, and effects to a series of signature lines that include everything from soup to nuts. Satch recorded the monstrous tones on Surfing armed only with a white Kramer Pacer (loaded with an original Floyd Rose vibrato and two Seymour Duncan pickups— a ’59 in the neck position and one of the first JBs in the bridge), a pair of homemade Strat copies, a Roland JC-120, a ’68 Marshall half-stack modded with a master volume, an original Chandler Tube Driver, a Boss DS-1 and an SD-1, a Scholz Rockman, a Nomad amplifier, plus a borrowed Fender Precision Bass and bass amp.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Soon after, Satriani began an ongoing relationship with Ibanez, a fruitful collaboration that started with Satch’s favorite JS-1, Chrome Boy, and which has since spawned at least a dozen different JS models. He also began using low-wattage Wells and Cornford amps in the studio. Nowadays you can outfit your entire rig—from guitars and amps (the aforementioned Ibanez JS signature series and Peavey’s JSX amps), to pickups and effects pedals (DiMarzio Mo’ Joe pickups, and Vox’s Satchurator Distortion, Time Machine Delay, and Big Bad Wah), to picks and straps decorated with Satriani artwork— by visiting satriani.com. As far as financing your solo album on a credit card goes, I’m not sure you could pull this off in our current economy, but you’ll never know until you try. Until then, you’ve gotta...

3. Subvert the ordinary

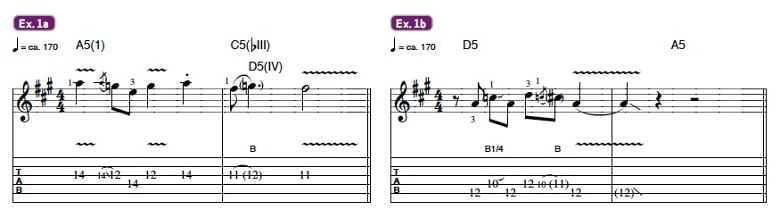

One of Satriani’s most brilliant early strategies was to subvert, re-energize, and recast common blues-rock licks as catchy and memorable instrumental “verse” melodies played over irresistible rhythmic grooves. Check out how familiar melodic snippets like the Beck-ish runs in Ex. 1a and Ex. 1b take on a whole new life when injected into a high-octane, eighth-note surf beat punctuated with root-5 power chords a la “Surfing with the Alien.” You can transpose these licks to their respective adjacent higher strings, but they sound throatier as written. Ex. 1c bears an unmistakable Hendrix imprint—that kind of heavy-blues-meets-Native-American-chant vibe—which can be enjoyed with or without the optional harmonies, and Ex. 1d follows suit, incorporating a dose of traditional call-and-response phrasing. Cool enough, but that’s just a part of the big picture. You’ve also gotta...

4. Be strange and beautiful

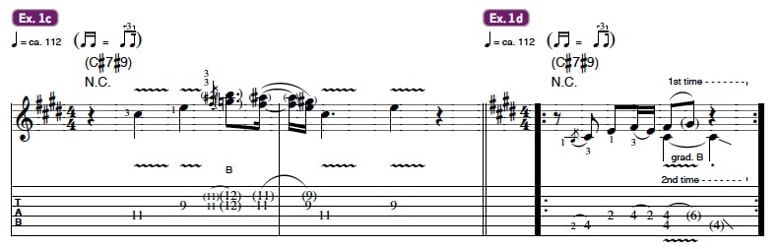

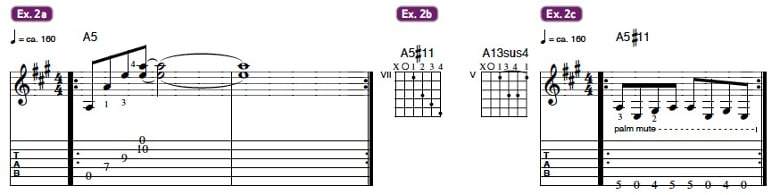

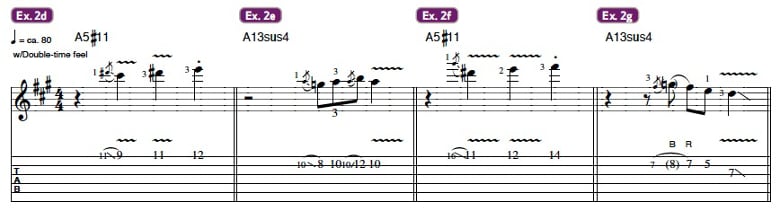

Exotic melodies, shifting modalities, and intriguing song structures are also key to the Satriani oeuvre. Wet your feet with the stock, arpeggiated A5 figure shown in Ex. 2a, apply its rhythmic motif and picking pattern to the A5#11 and A13sus4 voicings from Ex. 2b, and you’ll hear a pretty convincing approximation of Satriani’s other-worldly Vincent Bell Coral electric sitar intro to “Lords of Karma.” Ex. 2c simulates the bass groove that defines the song’s shifting A Lydian and A Mixolydian modalities. Play it as is for A5#11 and lower all G#s a half-step to G over A13sus4. (Tip: For total authenticity, tie the and of beat two to beat three.)

When Satch’s exotic melody joins the mix, it emphasizes key chord and scale tones that define each mode. Notated in half-time to conserve space, Examples 2d and 2f both feature precise grace-note slurs and outline the raw melodic materials Satriani used to sculpt A Lydian lines over A5#11—the 3 (C#), the #4/#11(D#), the 5 (E), and the 6 (F#)—while Examples 2e and 2g illustrate the shift to A Mixolydian via G (the b7) and D (the 4/11), plus the A, B, E, and F# inherent to both modes. Check out the recording for Satch’s exact rhythms and phrasing, and then get ready to...

5. Surf the board

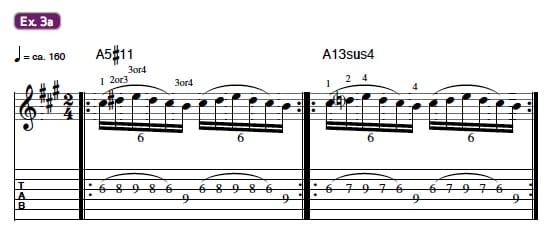

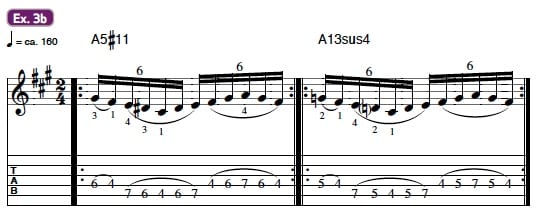

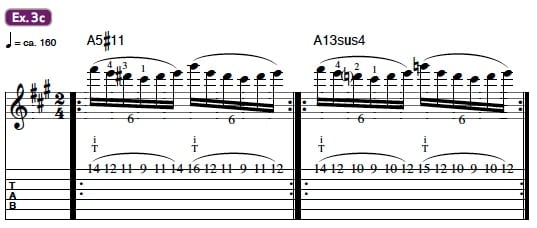

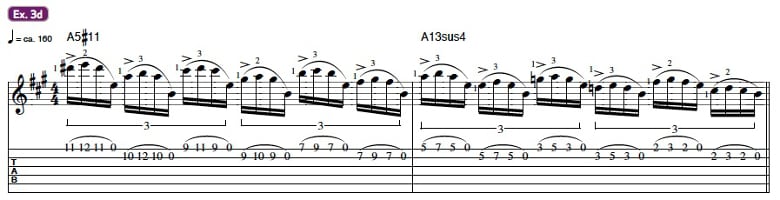

The fretboard, that is. Satriani’s extremely fluid legato technique, and its application to what he calls his “pitch axis” theory—essentially the organization of modalities or chord progressions around a common tone (A, in this case)—has thrilled many a 6-string surfer, and here’s how you can ride along. Utilizing the A5#11-A13sus4 progression from our previous examples, Ex. 3a illustrates how to make a short, repetitive legato line fit both chords with the least amount of fuss. The only difference between A Lydian and A Mixolydian involves the 4 and 7, so these are the only tones that need adjustment when switching between modalities. Thus, we only have to change D# (the #4/#11) to D (the 4/11) to make the transition.

The elongated run in Ex. 3b requires similar adjustments, plus changing all G#s to Gs to fit the progression, and the same principle applies to both the tapped legato runs depicted in Ex. 3c, and the wild, quarter-note-triplet-based, hammer-on/pull-off excursion shown in Ex. 3d. Try applying this concept to any combination of scales, modes, and/or chords. Just remember, you’ve also gotta...

6. Romance the wood and play some shweet stuff

“Always with Me, Always with You,” perhaps Satriani’s most recognized composition outside of the immediate guitar community, confirms how much beauty can be coaxed from a basic B major scale. The melody and accompaniment may sound simple at first, but don’t be fooled—closer scrutiny reveals Satriani’s obsessive attention to detail. The fourbar excerpt transcribed in Ex. 4 shows the opening melody and rhythm figure, and reveals not only how nearly every note has some sort of physical “Joe stuff” smeared on it (slurs, vibrato, pick harmonic, palm muting, etc.), but also how he imposes a unique harmonic imprint on an otherwise pedestrian chord progression. “It’s a simple I-IV-V progression, but I subverted it a bit by giving every chord a suspended tonality,” Satch recalled in 2007. “I would add, say a 4 to one chord, and a 13 to another.” (Tip: Be sure to “play” those rests—they’re just as important as the notes.) Ready to trip out? Let’s...

7. Take tapping into the fourth dimension

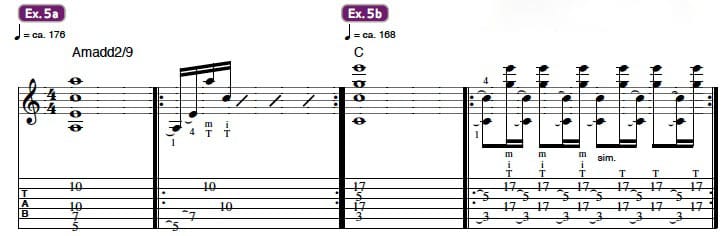

Satriani’s “Midnight” (which was composed on manuscript before making its way to the fretboard) was an epiphany for two-hand tappers. Determined not to repeat what had already been done, Satch devised an ingenious way to bring the piece to life by employing two different two-hand tapping patterns to play arpeggios and broken chords. The first approach is illustrated in bar 2 of Ex. 5a, which converts the hard-to-play Am voicing shown in bar 1 into two sets of tapped, arpeggiated intervals—the left hand taps the first two notes and the right hand taps the last two. (Tip: Use a string mute or tie a piece of cloth around the fretboard just above the nut to eliminate unwanted and untempered overtones from occurring behind tapped notes.) Likewise, bar 2 in Ex. 5b breaks an impossible C chord (bar 1) into a rhythmic blaze of easy-to-manage, two-hand, tapped intervals. (Tip: Think castanets!)

Now, here comes the fun part. First, apply the “voicings” in Ex. 5c to the tapping pattern you learned in Ex. 5a to approximate the song’s intro. (Note the variations in left-hand fingering/tapping.) Check the album for the order of these chords and their duration, and then follow the same procedure with the impossible voicings in Ex. 5dand the tapping pattern from Ex. 5b to simulate the main theme, which maintains a constant fingering and tapping pattern throughout. Giddyap and...

8. Go nuts

Anyone who has witnessed his live show can attest that one of Satriani’s most endearing qualities is how the guy just cuts loose with some of the craziest licks ‘n’ tricks you never thought of. From screaming, near-dog-whistle harmonic dive bombs (that super-high A harmonic on the 3rdstring/ 2nd-fret is a favorite), and the “lizard-down-the-throat” sound (a warble- y, whammy effect achieved by sliding a note up a string while simultaneously depressing the bar to maintain the same pitch), to hooking the B or G string under his ring-fingernail and yanking it off the side of the neck (a Steve Vai fave), and using the side of his pick to tap hyperspeed trills, Satriani always manages to transcend gimmickry and find truly astounding musical applications for even the wackiest sounds and techniques.

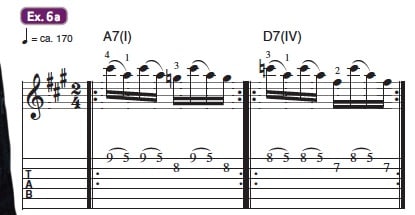

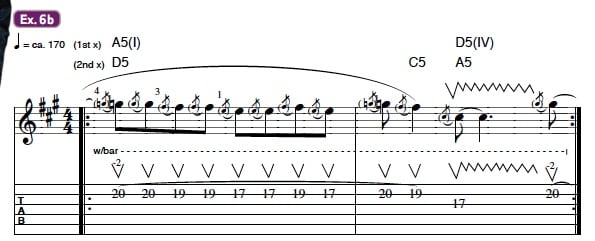

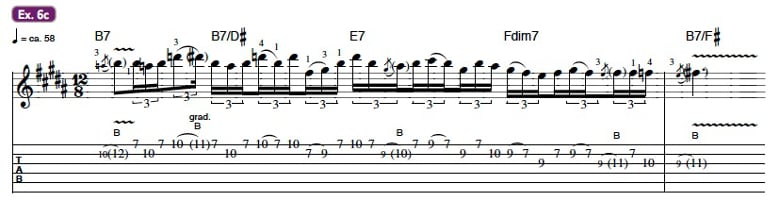

On a more note-y level, have fun surfing the electric hoe-down stylings in the I-IV lick in Ex. 6a (Tip: Play bar 1 three times, bar 2 four times, and bar 1 once to ride a four-bar 4/4 figure.), and the whammy antics in Ex. 6b. (Shades of Tommy Bolin!) Pick every note if you like, or play it as written. And of course we all know Satch is a master of deep electric blues à la Hendrix’s “Red House,” as heard in the busy but tasty turnaround notated in Ex. 6c. Read it and weep, and then...

9. Write yourself a signature song

“Satch Boogie” isn’t just a theme song, it’s a rite-of-passage for thousands of Satriani disciples, and I’m pleased-as-punch to finally get my own shot at translating its sheer power to the printed page. The song certainly requires chops to spare, but its primary component is attitude. Ex. 7 lays out the entire head, from the Buddy Rich hi-hat intro right up to Satch’s first solo. Take your time, follow the repeat, D.S., and Coda instructions, and the occasional odd-time measure, and you’ll be navigating the cosmos before you know it. But before we split, you gotta...

10. Just ask the axis

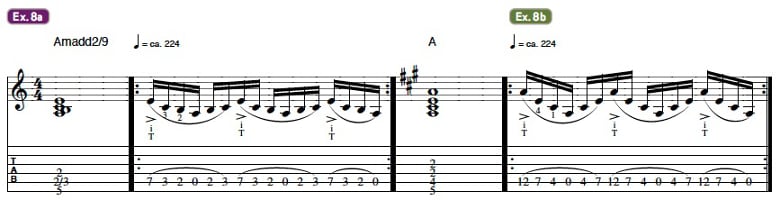

The pitch axis, that is. When Satch takes his signature boogie to the bridge, all heaven breaks loose in a fearless cascade of flange-y, tapped arpeggios played entirely on the A string. “I started out taking a ZZ Top/Van Halen-style boogie, and injecting this warped two-handed tapping thing in the middle,” explains Satriani. “But the devil on my shoulder urged me to do more, so I used pitch axis theory again. As a result, the notes that make up the two-handed arpeggios in that section create some very odd tonalities that you wouldn’t hear on a ZZ Top album.”

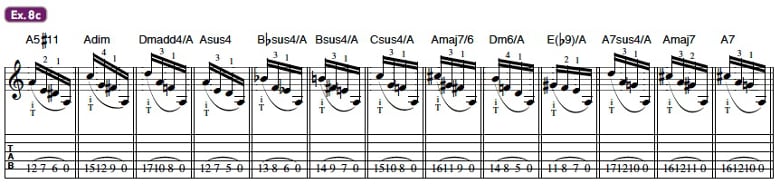

Ex. 8a demonstrates how Satch’s concept can be applied to an A minor scale motif, while Ex. 8b spreads it out over an A major arpeggio. Note how the sixteenth-notes are grouped six-six-four, and how the pick-hand tap-points punch out a half clave or basic rock-and-roll rhythm (two dotted-eighths, plus a quarter-note), while the fret hand covers pull-offs and hammer-ons to and from an open A string. (That’d be your pitch axis.) Practice these moves until you feel ready to meld each of the of four-note arpeggios shown in Ex. 8c to the previous six-six-four sixteenth-note scheme, and then have at it, one bar at a time, over and over until you nail it. Of course you’ll need to consult the album for the actual chord progression, as the arpeggios are listed here only in their order of appearance. Your mission, should you decide to accept it, is to take the ball and run with it. Let these ideas elevate your playing to new realms of creativity and inspire others to do the same. Pay it forward, kids!

Finally, I urge everyone to explore Satriani’s strange, beautiful catalog. Apologetic note to Joe: Man, I hope you can forgive my doting on the past, but it’s just that damn good!!