Have the Same Old Blues Chord Shapes Become Stale and Boring? Here’s How to Avoid Sounding Predictable

Avoid the trap of humdrum chords by getting command of a few alternate dominant voicings

If you’re at all intimidated by the term dominant voicings, relax – they’re only nominally tough, and their alternate cousins contained here amount to little more than a few fancy blues chord voicings.

In classical theory, the chord (V7) formed from the 5th degree of the diatonic scale is dominant; that is, it contains a b7th. The blues, though – as a form of folk music which casts aside theory as though it were wheat chaff – also tends to favor dominant rather than major voicings of the I and IV chords.

Blues guitar progressions, because of their repetitive nature, provide a sturdy foundation over which to jam infinite melodies and riffs. That said, blues forms that rely too heavily on the same old chord shapes can grow boring and predictable. Thankfully, you can avoid this trap by getting command of a few alternate dominant voicings.

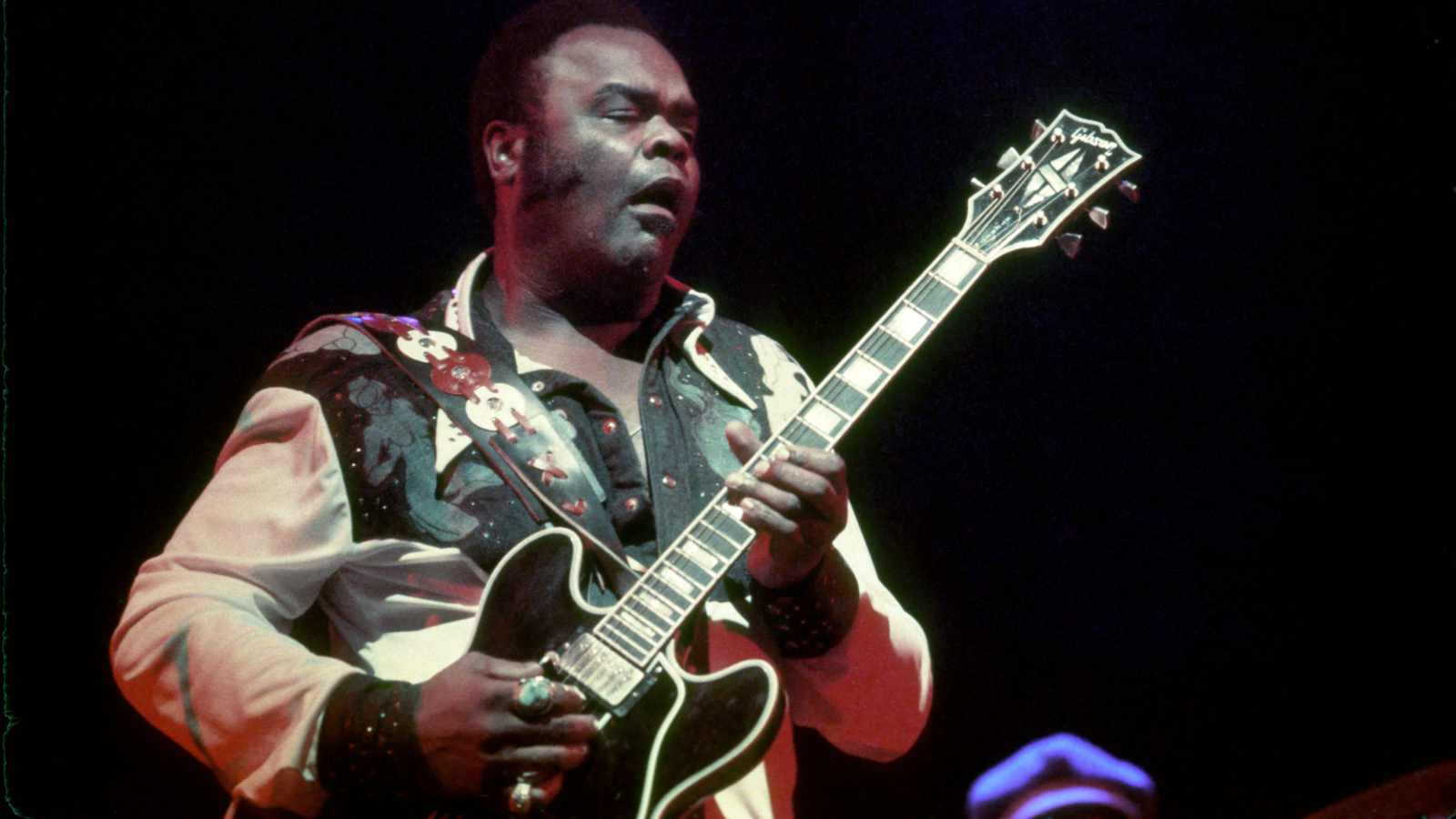

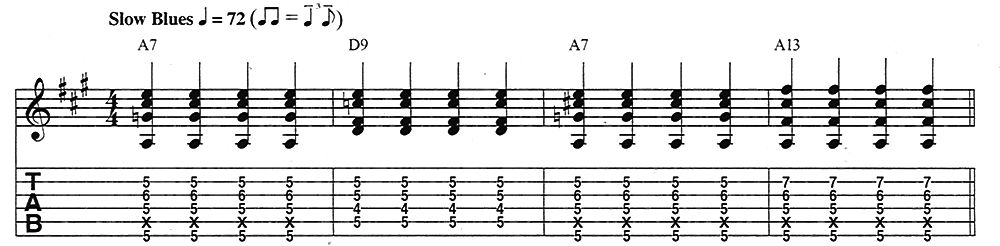

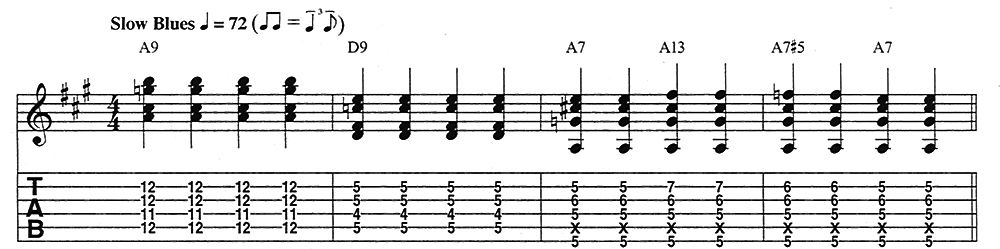

Figure 1 represents measures 1-4 of a slow blues, with a “fast change” to the IV (D9) chord in measure 2.

The A13 chord in bar 4 adds a pinch of spice while helping advance the progression toward the IV chord that awaits in bar 5 (not shown).

The remaining figures here present four more ways to break free of basic blues voicings.

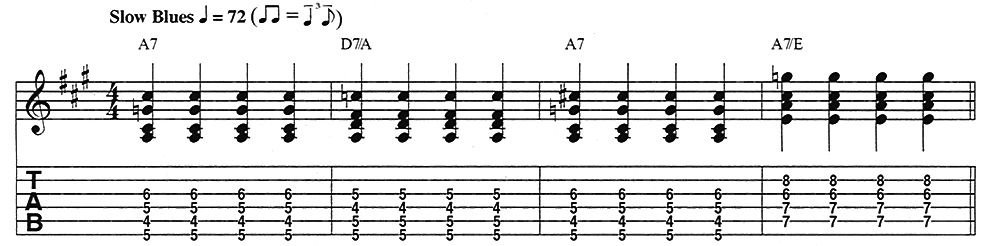

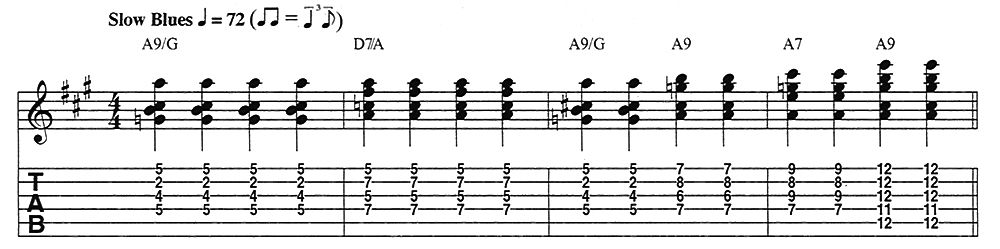

Thick, bass-heavy chord forms give Figure 2 a distinctive flavor that’s perfectly suited for a low-down, nasty blues.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Observe the smooth voice-leading between the A7 chord and the 2nd inversion (5th on bottom) D7/A, where the top three notes move only one fret, while the low A is maintained as a common tone.

This movement sonically compresses and concentrates the tonality until measure 4, when a 2nd-inversion A7 chord (A7/E) pushes it upward.

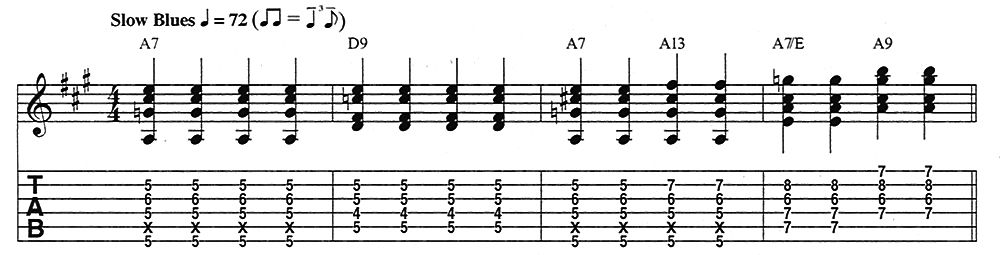

Figure 3 begins conventionally enough, with standard A7 and D9 chords in measures 1-2, and then gains momentum in measures 3-4.

On paper, the A7-A13-A7/E-A9 changes may appear rather random, but you’ll understand the sequence’s function when you play it.

The top-string notes (E, F#, G, and B) ascend in a melody derived from the A Mixolydian mode (A-B-C#-D-E-F#-G).

Bars 1-2 of Figure 4 feature parallel-9th voicings (A9 and D9).

Bars 3 and 4 are more harmonically active, as the top notes ascend from E to F# (A7-A13) before descending chromatically to F and, finally, back to E (A7#5-A7).

Dig the sophisticated musical tension and subsequent resolution that result from the A7#5-A7 change.

Finally, Figure 5, inspired by Freddie King’s “Hideaway,” adds some Texas hot sauce in the form of a hip A9/G chord (3rd inversion, b7th on bottom), which sets up a jazzy vibe.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.