Here’s Some Blues You Can Really Use

Improve your playing with this master class on everything you need to know for better blues.

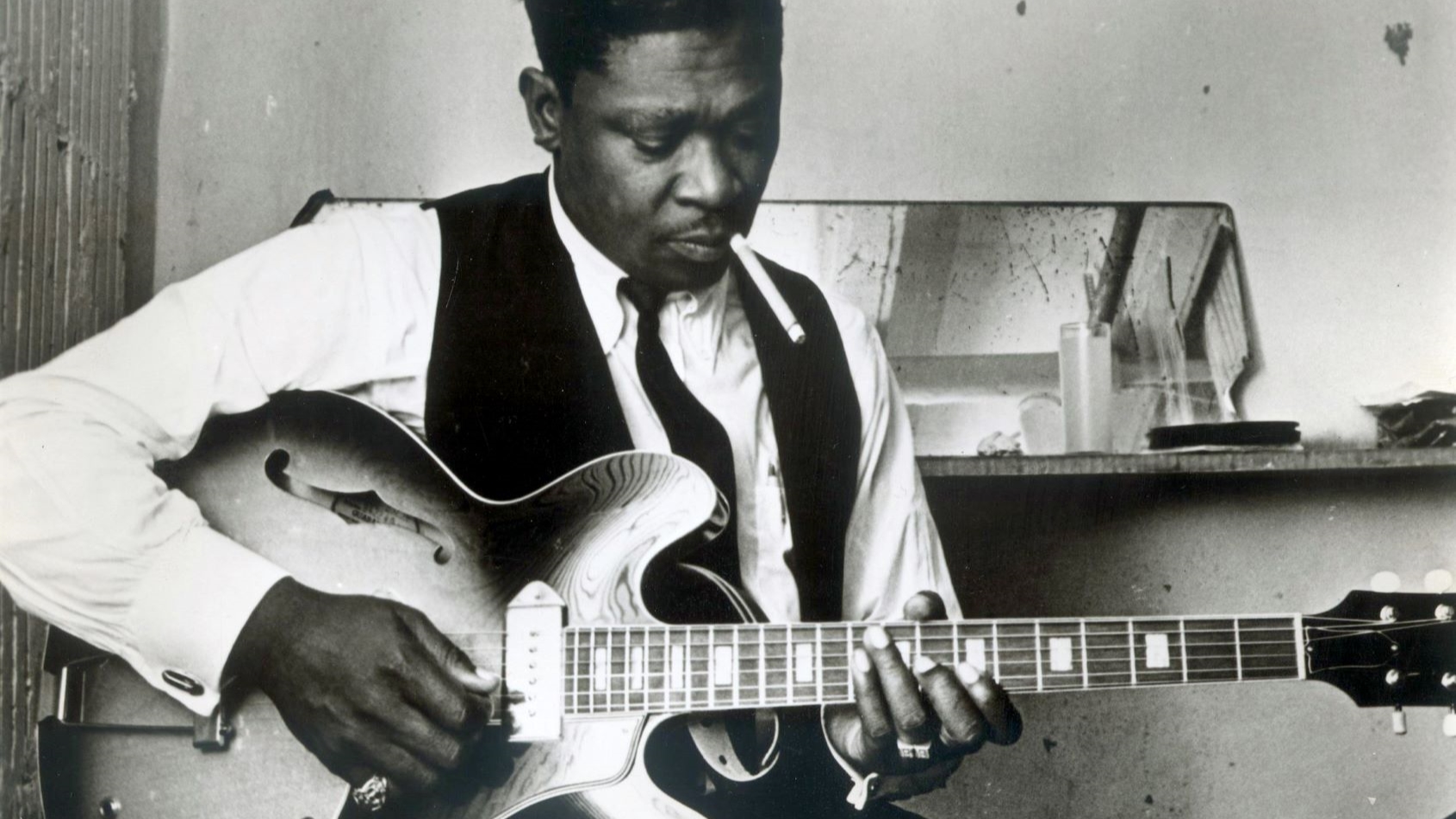

The traditional blues players from the 1920s through the ’60s established many popular song structures, chords and guitar techniques. It’s testament to the quality and enduring popularity of these artists that so much of the identity of their playing can still be heard in today’s blues music.

Less well known is that blues is at the heart of much of the rock and metal that would emerge from the ’70s on – so there’s something for everyone to learn. What more reason do you need to follow our lesson on some core blues basics?

Classic Blues

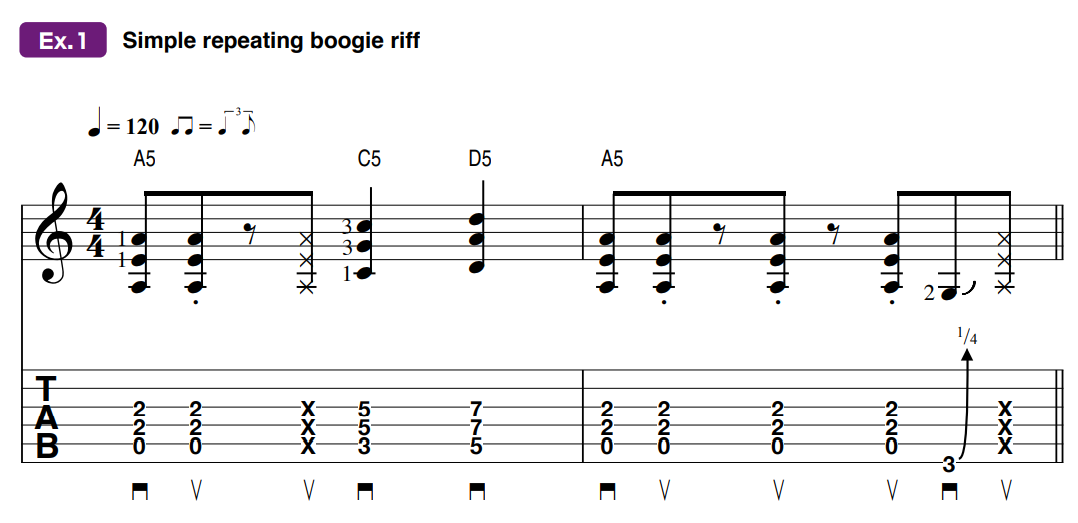

Get jamming the easy way, with a simple, traditional repeating boogie riff in the style of the great John Lee Hooker (Ex. 1). Based around an A root note, this line can easily be taken through a standard 12-bar blues progression (A - D - E) by shifting the pattern up one string to a “D shape” riff and down one string set for the E chord.

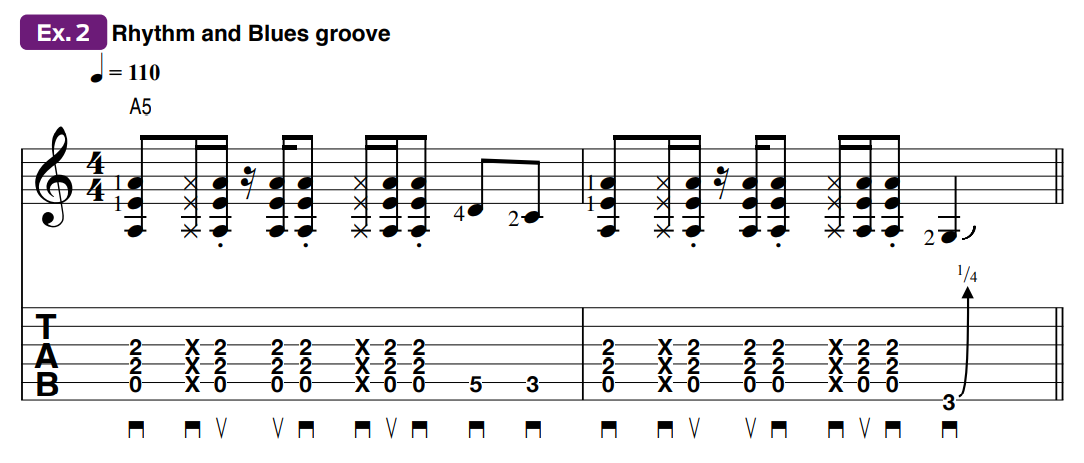

Ex. 2 uses the rhythm and blues groove first popularized by Bo Diddley in his self-titled 1955 single and known today as the “Bo Diddley beat.” It’s been adapted by many artists, including the Rolling Stones in “Not Fade Away,” Bruce Springsteen in “She’s the One” and George Michael in “Faith.”

This catchy groove is all about the rhythm and timing, so strum slowly at first, then try using some other chords you know. To achieve the desired feel, keep your picking hand moving in a continuous, uninterrupted down-up-down-up manner with the underlying 16th-note pulse, even during the rests.

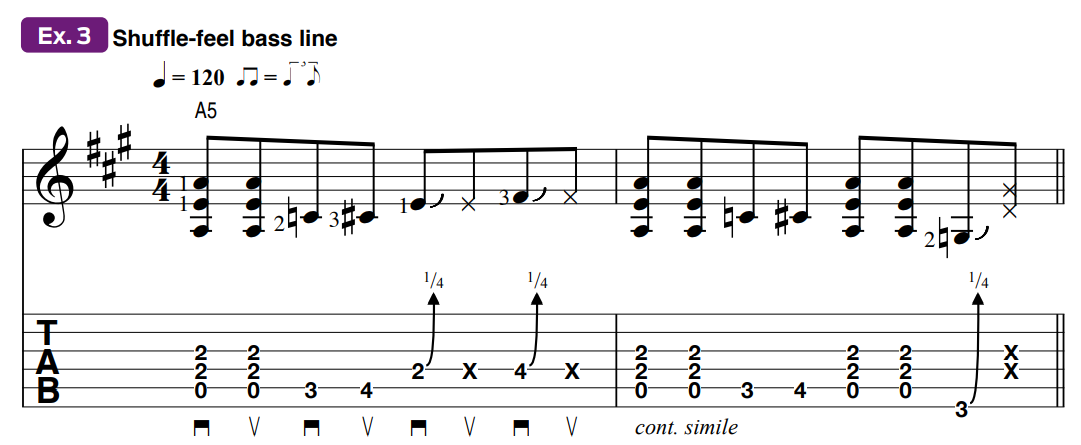

Stevie Ray Vaughan was famed for the shuffle rhythms and ferocious lead work he’d coax from his “Number One” Strat. In Ex. 3, a blues bass line is woven around an open A5 power chord. You get the weight of the chord while the bass line outlines a more sophisticated A7 harmony. Listen to SRV’s “Pride and Joy” and “Rude Mood” for inspiration.

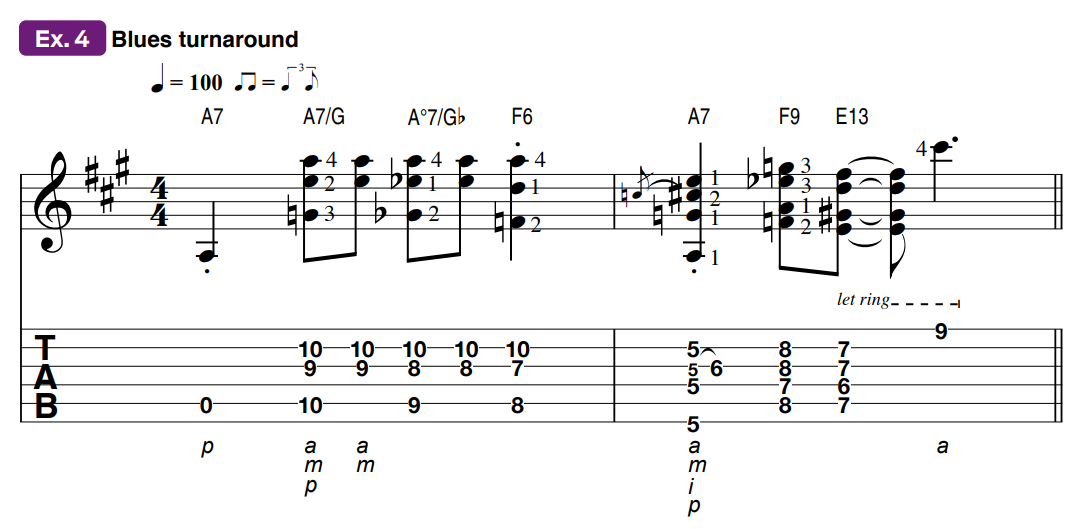

Ex. 4 shows a blues turnaround inspired by Eric Clapton, who adapted Robert Johnson-style changes to electric blues guitar. Playing fingerstyle will help make all the melody notes and the descending bass notes ring out clearly.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

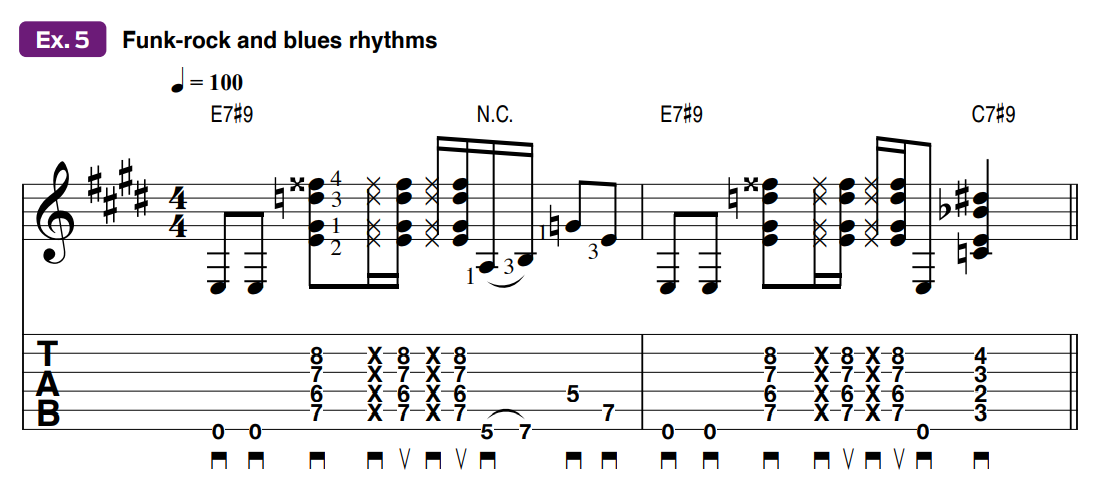

Funk-rock blends nicely with blues rhythms, as Jimi Hendrix demonstrated in many of his classic tracks. Ex. 5 is informed by his style and employs one of his favorite chords (the 7#9, often dubbed “the Hendrix chord”) played in both E and C. In the single-note part of the riff, you can pull the 5th-fret G note slightly sharp for an even bluesier flavor.

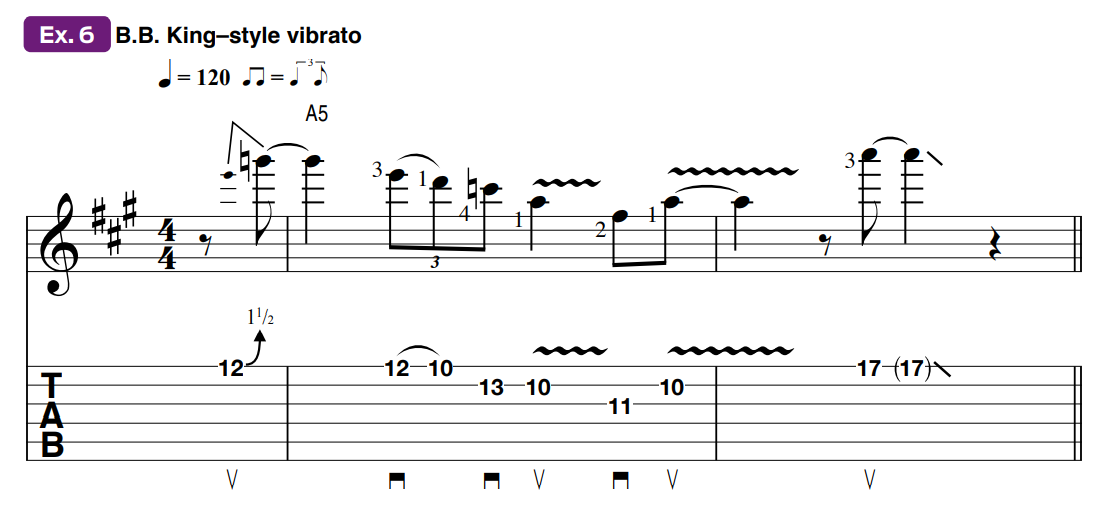

B.B. King was famed for his soulful touch and his quivering “butterfly” vibrato technique, which is deftly employed with the A note in Ex. 6. To emulate B.B.’s signature sound, aim for a quick wobble of the string but without too much pitch change. Rest the base of your fretting finger on the side of the fretboard then “flutter” your hand around this pivot point to create the vibrato. It’s easier than using pure finger strength, and it’s pure B.B.

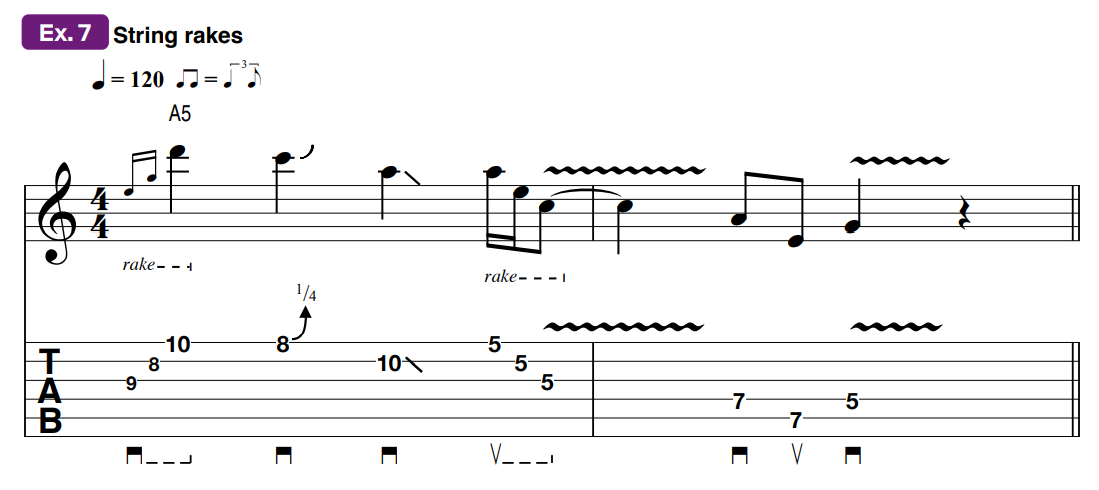

In blues circles, a mini sweep across the strings is referred to as a rake. This drag of the pick is more of a percussive effect, so the notes don’t need to be perfectly fretted. You can even mute the strings entirely as you pick, so that the rake notes are pitchless “chucks.” We’ve written picking directions for the rakes here (Ex. 7). Notice how the quarter-tone bend in bar 1 provides a blues edge too.

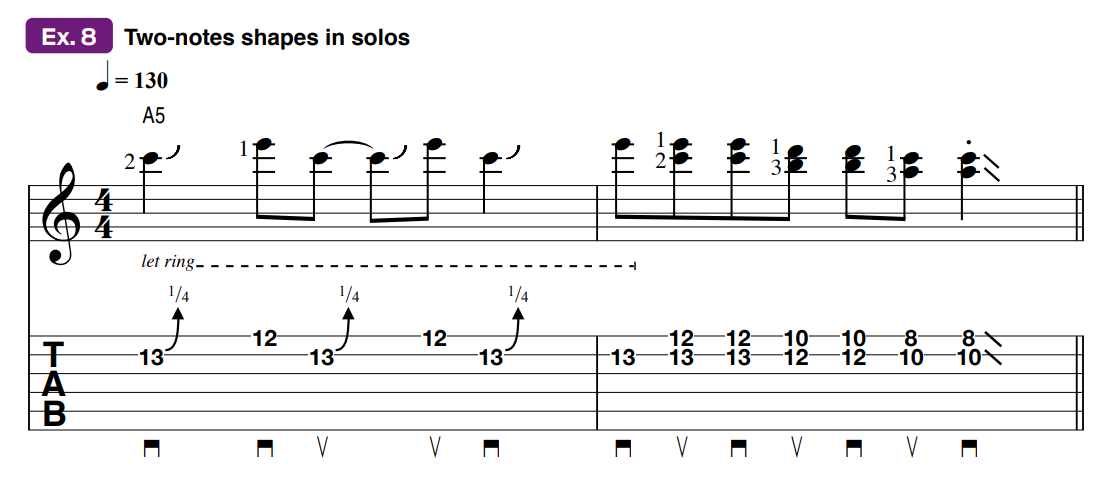

Playing two notes at once is a great way to thicken up your guitar sound. This is an effective thing to do to help avoid the dreaded “tone dropout” you might experience when soloing in a power trio. Ex. 8 is inspired by John Mayer, and in bar 2 we’re playing a line that descends the B and high E strings in diatonic 3rds strings, sweetly harmonizing the key of A minor.

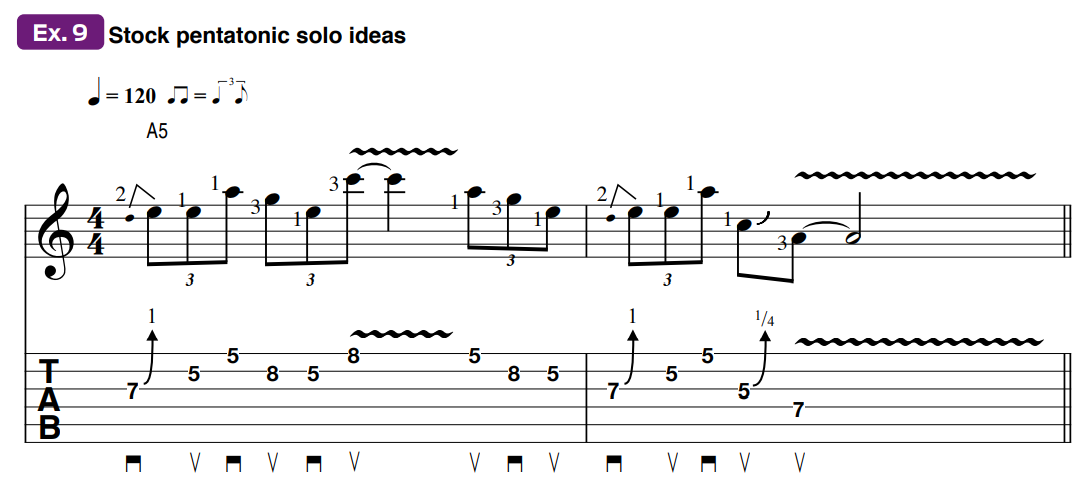

From Eric Clapton to Joe Bonamassa, great blues guitarists seem to have a never-ending vocabulary of stock phrases, yet they somehow always sound authentic. The key is to use the minor or major pentatonic scale as a foundation and keep your solos simple at first. In Ex. 9, we’re playing a very triplet-y phrase based on the A minor pentatonic scale (A, C, D, E, G) and presenting ideas that can be reimagined in myriad ways.

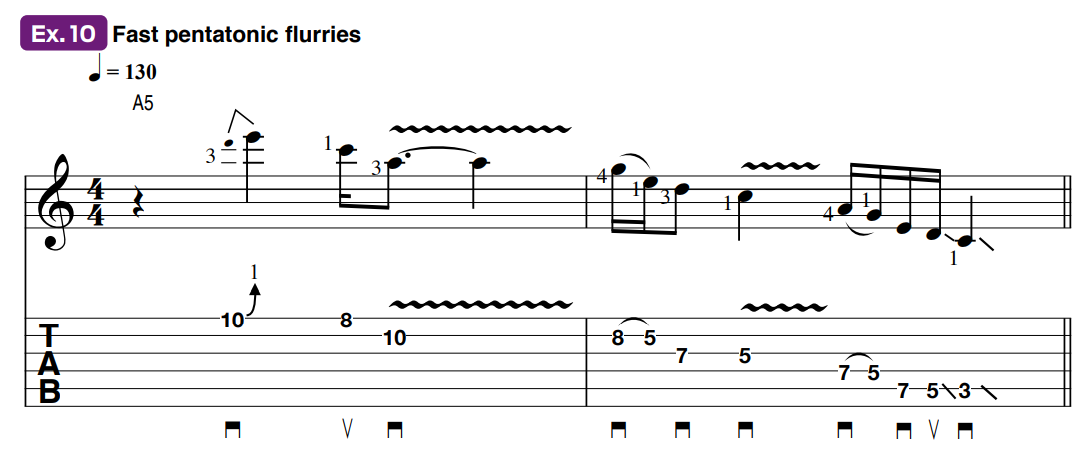

With some minor pentatonic basics under our belts, we can expand these ideas into something more sophisticated, using fast pentatonic flurries, as demonstrated in Ex. 10. Legendary bluesman Buddy Guy often plays fast flurries of notes, straight from the minor pentatonic scale. That means the shape feels familiar but you’ll be delivering more “angular” phrased licks.

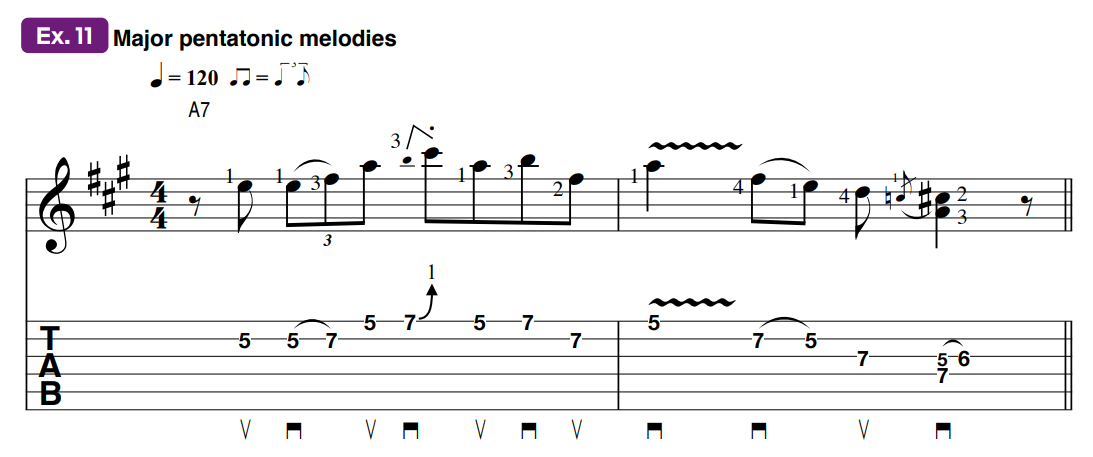

Blues isn’t only about minor keys. Listen to Freddie King’s “Hide Away” and Fleetwood Mac’s “Need Your Love So Bad.” Both of these songs feature extensive use of the major pentatonic scale (intervallically spelled 1, 2, 3, 5, 6). The simple lick shown in Ex. 11 is designed to help get you started with this warm-sounding set of notes. Watch out though. There’s a bluesy minor note in there too – the 5th-fret C, right before the last dyad (two-note chord).

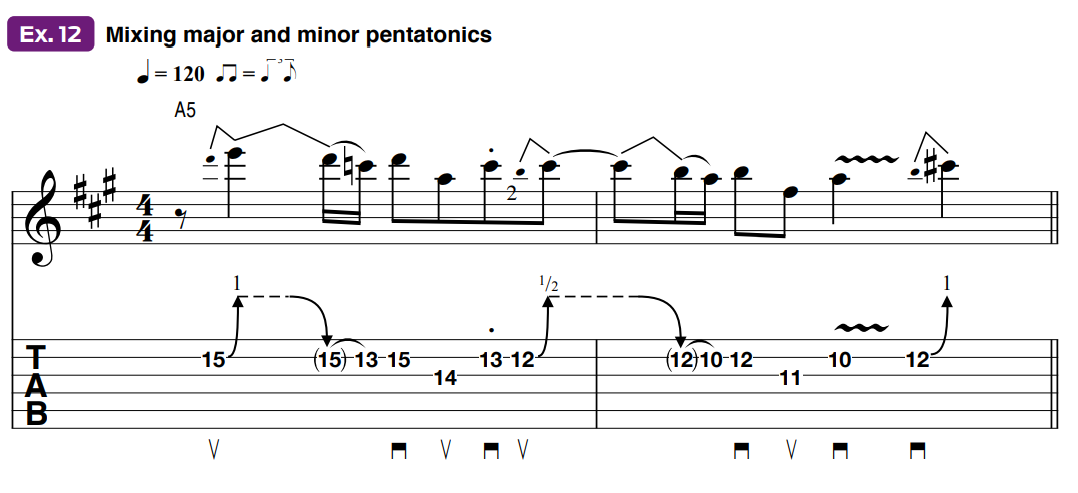

The previous lick hinted at an idea we’re going exploring more fully in our next example – mixing up parallel major and minor pentatonic scales in solos. Why bother? Well, the combination of “happy” major and “serious” minor scales sounds way more sophisticated than sticking to just one or the other. Ex. 12 keeps things simple, but this idea is a key part of blues, so experiment!

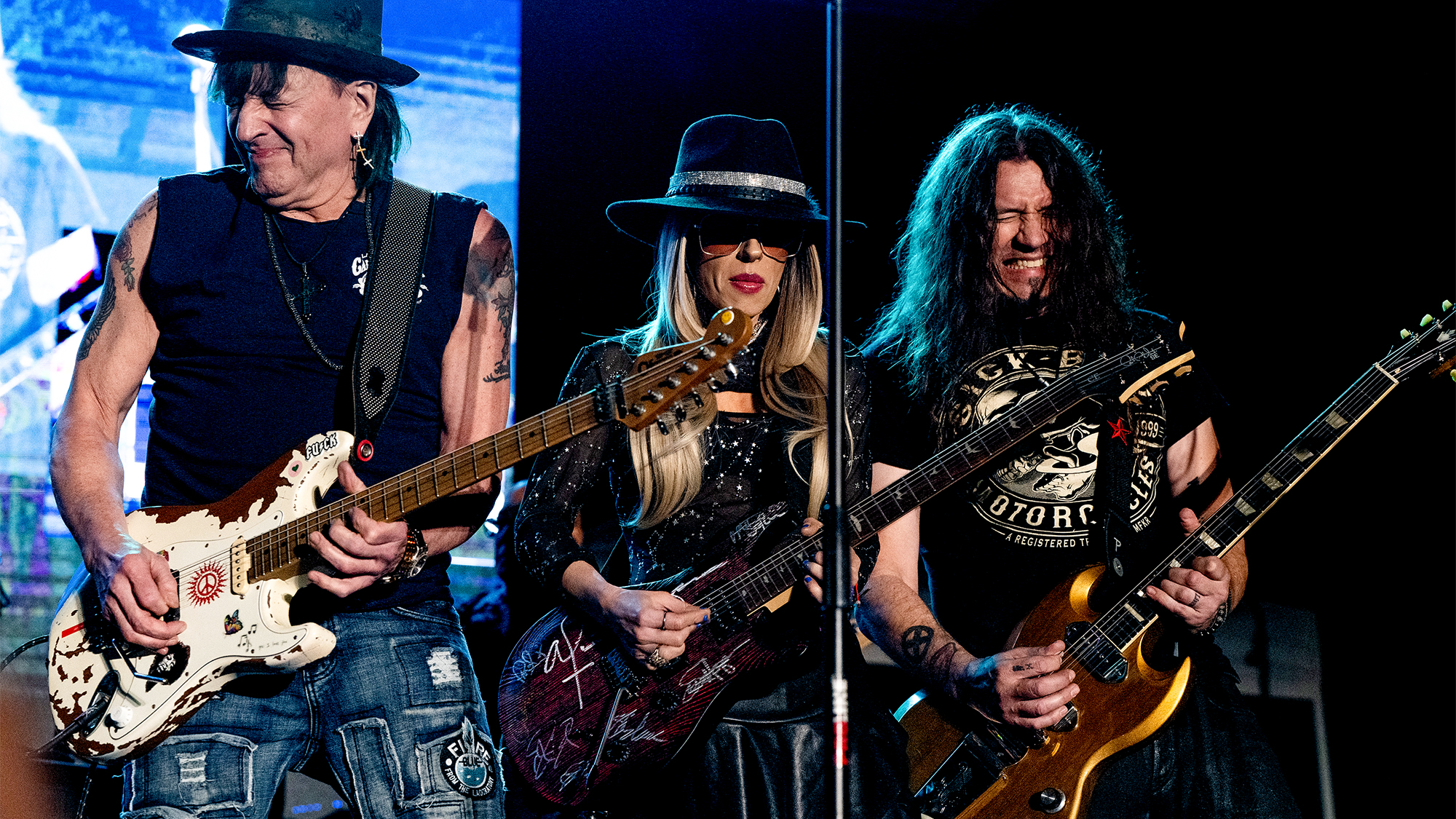

21st Century Blues

Whether it’s the fuzz-fuelled lo-fi riffing of the White Stripes and the Black Keys, or the Zeppelin-like hard rock sensibilities of Rival Sons and Greta Van Fleet, it’s fair to say that blues has evolved somewhat in recent years.

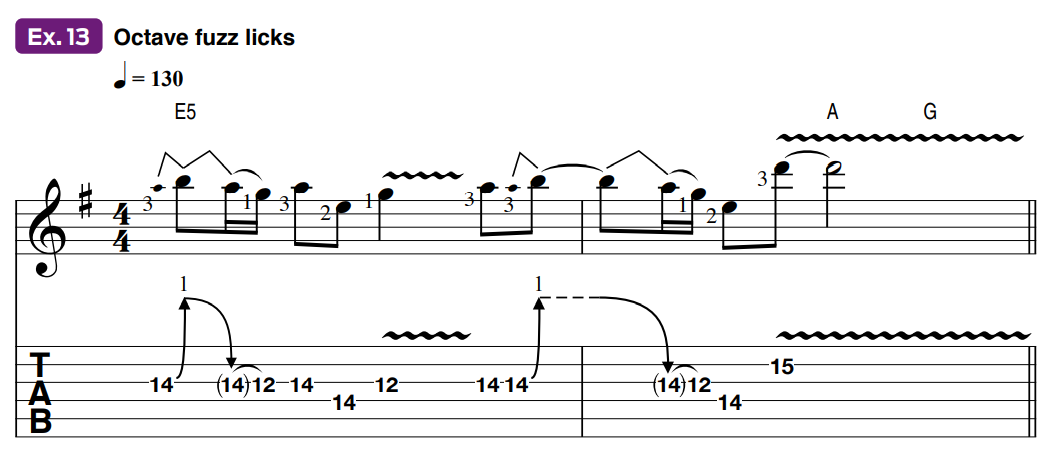

Though many of the chords and scales owe a debt to earlier forebears, many bands are putting their own stamp on blues with retro-inspired drive tones and tone-bending effects like octavers and wild fuzz distortions. Here we’re looking at a few of the tricks and riffing tropes of the current generation of blues players.

Dan Auerbach

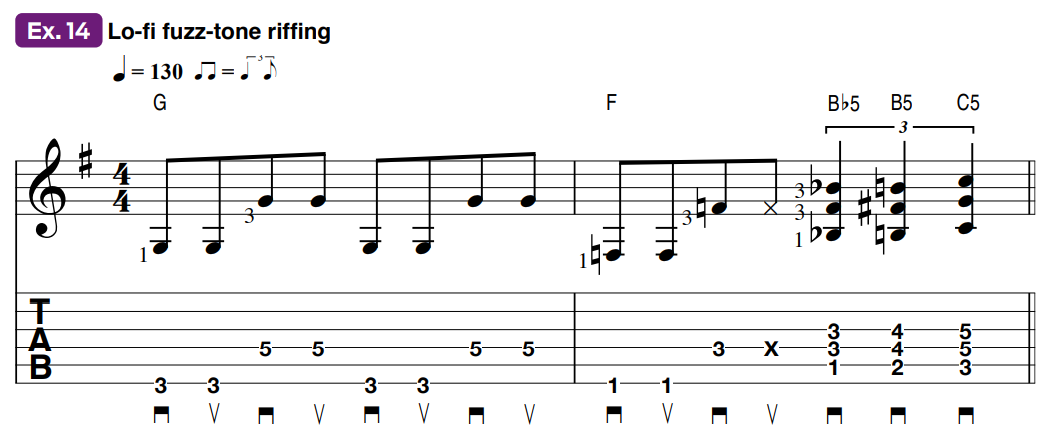

Spiky fuzz distortion tones have been a big part of the signature retro sounds of the aforementioned bands. The riff shown in Ex. 14 is designed to make good use of a dirt pedal. If you’re using a regular drive pedal, keep the treble high, roll off a little bass and experiment with your amp’s EQ and gain.

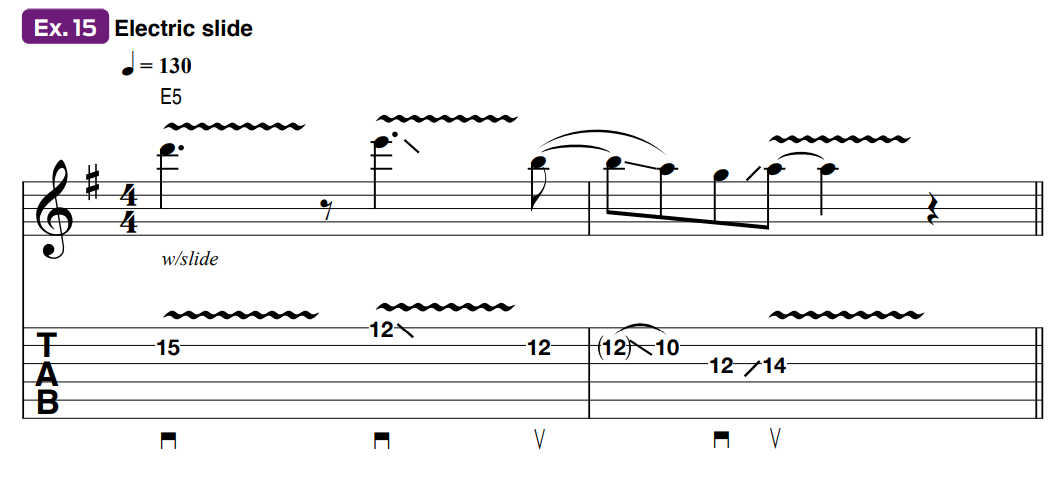

From Robert Johnson and Elmore James to Derek Trucks, Gary Clark Jr. and Auerbach, slide guitar has long been at the heart of blues. The simple electric slide lick shown in Ex. 15 will help you develop this tricky technique.

Place your slide on your 3rd or 4th finger and aim directly over the fret you’re playing (not behind it). Use your 1st finger to dampen the strings behind the slide and suppress unwanted string noise and overtones. Additionally, it helps to use your pick hand to mute the strings your not playing on at the moment.

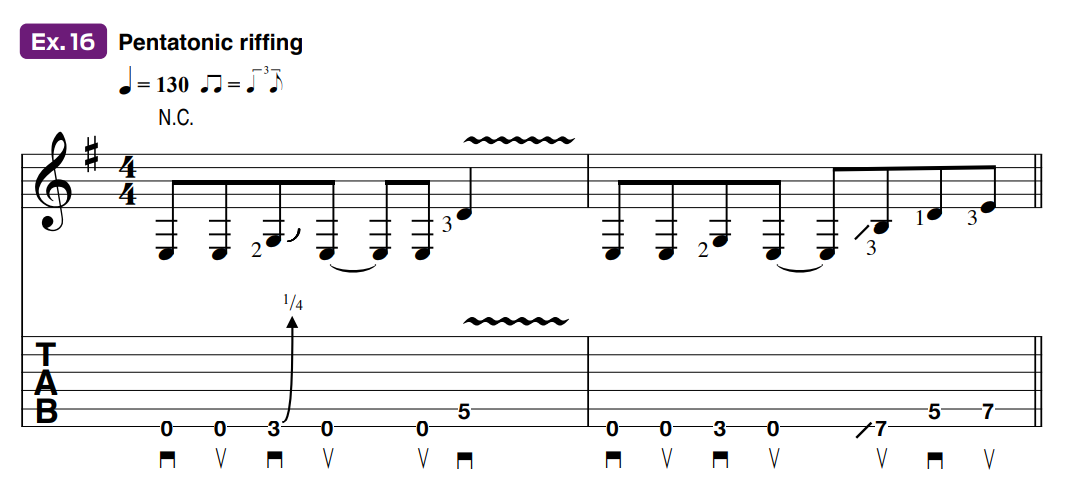

Contemporary bands’ minor pentatonic riffs owe as much to ’70s rock as they do to early blues. The pentatonic riff shown in Ex. 16 could easily be a Black Keys tune, a Led Zeppelin line, or you could slow it down and give it a traditional “Hoochie Coochie Man” treatment. It describes an E minor tonality, so the 6th string can be used as your tonal center to “bounce” the other notes off.

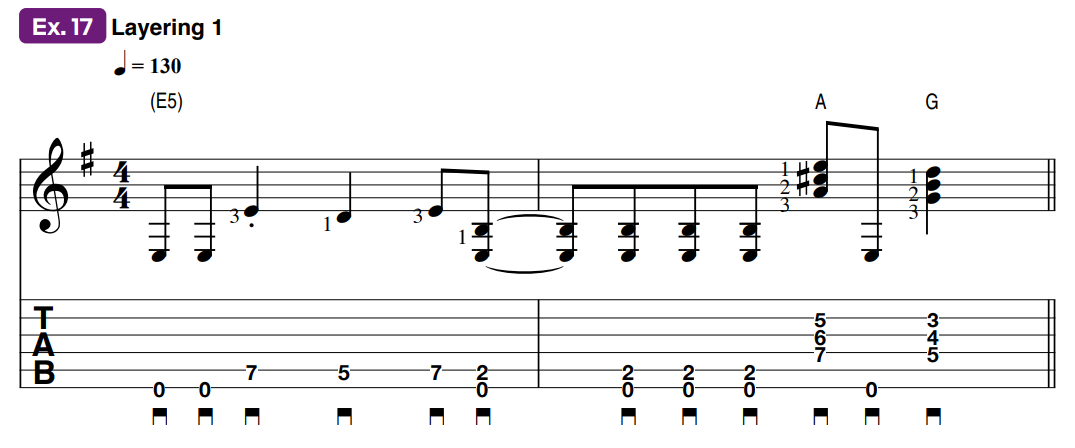

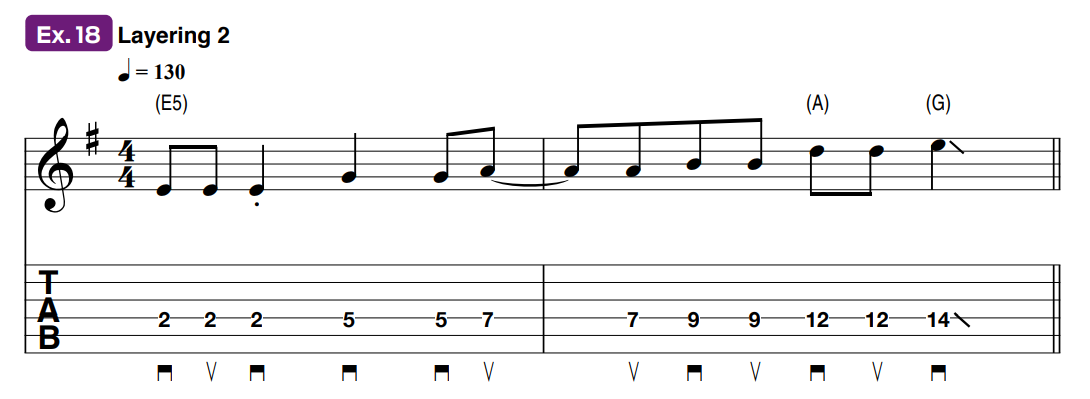

The advent of multi-track recording in the ’70s saw bands double-tracking guitar riffs. In recent years, duos like Royal Blood have used switching systems to recreate the effect in live performances. The layered riff in Ex. 17 is ideal for two guitars.

We take this idea further in Ex. 18. Here, we’re playing a simple melodic line on top of our previous riff. To make sure it stays riffy, we’re following the same rhythm for both lines – no solo widdle here! It’s based on the E minor pentatonic scale (E, G, A, B, D) throughout.

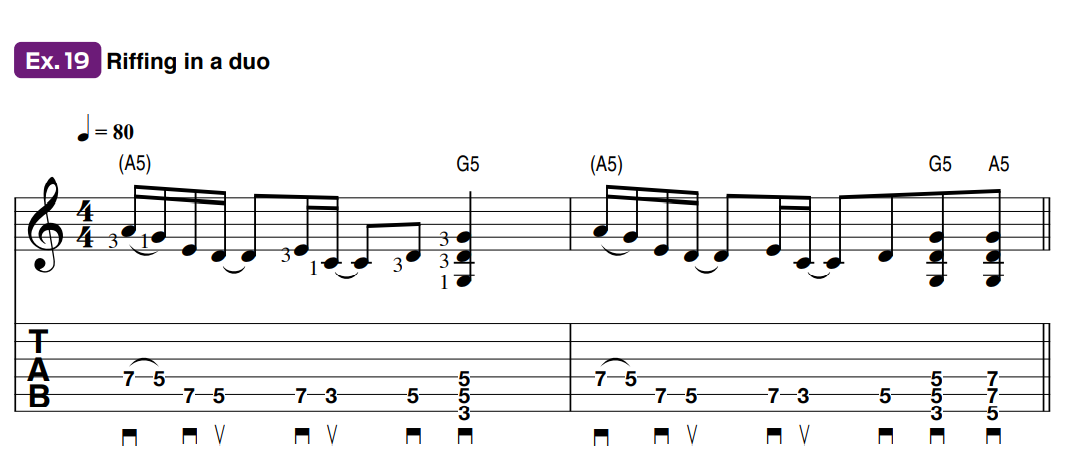

If you’re playing in a guitar-drums duo, White Stripes-style, you’ll need to fill out your sound. Ex. 19 covers plenty of notes to provide a full backing sound, then punctuating them with some fat-sounding power chords. For more weight, think about using an octaver effect as Jack White and Auerbach and Royal Blood’s Mike Kerr might do.

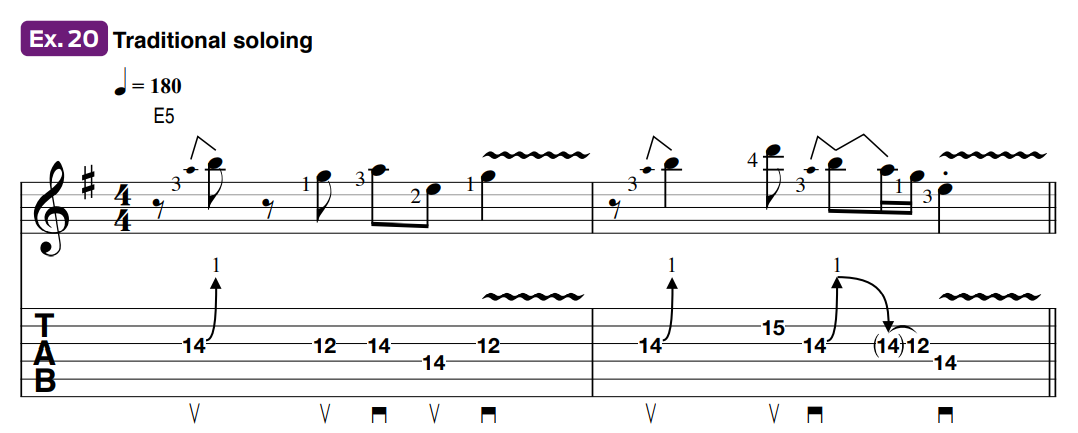

Even simple minor pentatonic licks can kick a song’s proverbial rear end. Ex. 20 demonstrates this with a lick inspired by Auerbach’s fretwork on the Black Keys song “Eagle Birds.”

Jon Bishop is a UK-based guitarist and freelance musician, and a longtime contributor to Guitar Techniques and Total Guitar. He's a graduate of the Academy of Contemporary Music in Guildford and is touring and recording guitarist for British rock 'n' roll royalty Shakin’ Stevens.