Have You Exhausted the Possibilities of Open Chords and Barre Chords? Here’s How to Make Your Progressions Sound More Interesting

Learn the art of ‘voice leading’ with examples inspired by Jimmy Page, Eddie Van Halen, Randy Rhoads and more

At the beginning of every guitarist’s musical journey, you learn a set of open “cowboy” chords and barre chords – a few major, minor and 7th shapes that set you on your way to playing every song in an “easy guitar” songbook.

But where do you go after you’ve exhausted all the possibilities of these stock shapes, and how do you expand on the textures of common progressions to make them sound more interesting?

One sure-fire way to do this is to incorporate voice leading into your playing. Voice leading is a musical concept that dates back to the Baroque era of classical music. It involves treating chords not as block shapes that move indifferently from one to another but as groups of individual, single-note “voices” that weave melodically through a progression.

Voice leading is a musical concept that dates back to the Baroque era of classical music

This usually means moving each voice as little as possible from chord to chord through the use of inversions – chord shapes that employ a note other than the root as the lowest note – and chord extensions – nonchord tones added atop a triad or 7th chord.

Traditionally, the rules of voice leading, established by Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries, were strict and uncompromising. For example, parallel 4ths, 5ths and octaves were not allowed, a prohibition that would make so much great modern music “illegal,” and voices – which were likened to the bass, tenor, alto and soprano parts in a choir – could not be crossed (i.e. moved outside of their register; for example, making a lower voice at a higher pitch than a higher voice).

But today, the only hard and fast rule in voice leading is that it must be melodically interesting without disrupting the flow of the chord progression.

This lesson will explore different methods of achieving this kind of harmonic bliss through voice leading. Since our focus will be on music theory rather than technique, pay attention to the picking and fingering notation in the examples, as we won’t be discussing it.

TYPES OF MOTION

Let’s start by looking at the two different types of melodic motion, the most common of which is stepwise motion, or moving up or down by only one scale degree, either a half step or a whole step.

Stepwise motion is common because the primary objective in voice leading is to have the individual voices move as little as possible, in order to produce smooth chord changes or transitions.

That said, in some situations it may be more melodically interesting to move an interval, or distance, greater than a half step or whole step. It all depends on how the other voices are moving.

The other type of melodic motion is what’s known as skip-wise, or disjunct motion, for which a melody note moves either up or down by an interval greater than a whole step, such as a minor or major 3rd or a perfect 4th.

Let’s see how these two types of melodic motion work together to form harmonic motion, the way two or more notes move together through a chord progression.

To demonstrate the types of harmonic motion, each part of our first group of examples will use the same stepwise ascending or descending melody in the top voice, while the bottom voice will differ each time.

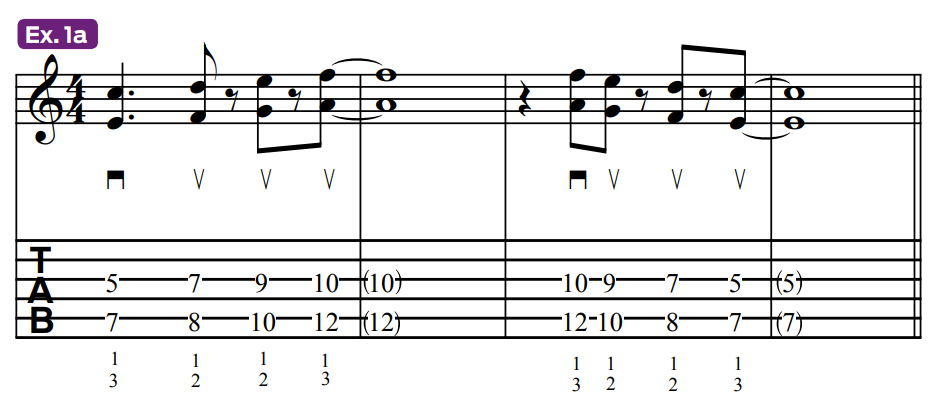

Ex. 1a utilizes parallel motion, for which two or more voices move in the same direction, up or down, by the same general interval from one chord to the next.

We start with the notes E and C above it, which form the interval of a minor 6th. Then, each voice ascends through the C major scale (C D E F G A B ) from its respective starting point, maintaining the relationship of either a minor or major 6th between it and the other voice, until peaking at the note pair A and F and descending back down to E and C.

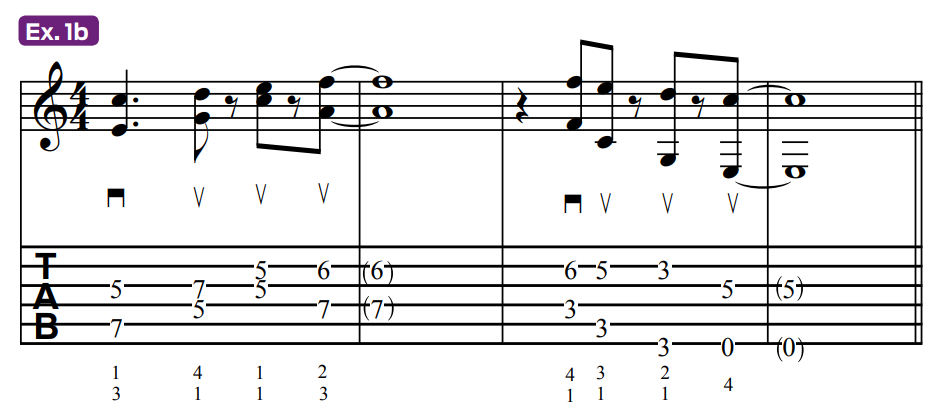

Ex. 1b illustrates similar motion, whereby two voices move in the same direction but by different intervals.

Here, the top voice is following the same melody line as before, and the bottom voice is moving in the same direction, but now by different, wider intervals (skip-wise motion).

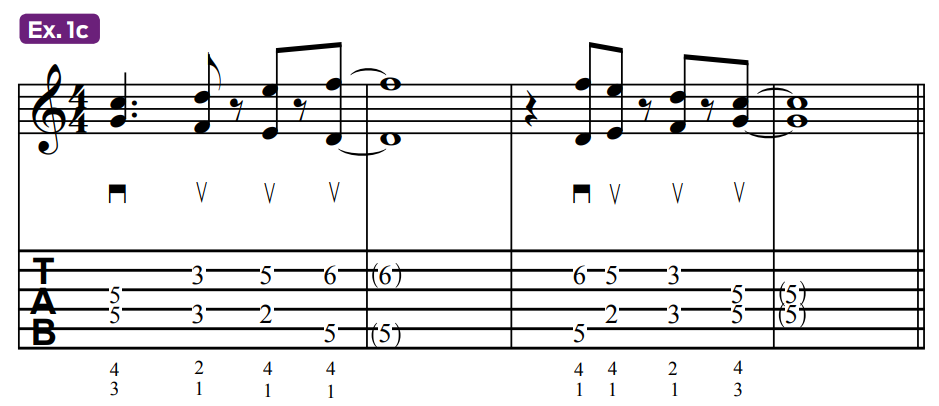

Ex. 1c demonstrates contrary motion, in which the two voices move in opposing directions.

Here, the voices are working in direct counterpoint, with the bottom voice moving in the opposite direction from the top voice note to note, which creates an especially interesting sound.

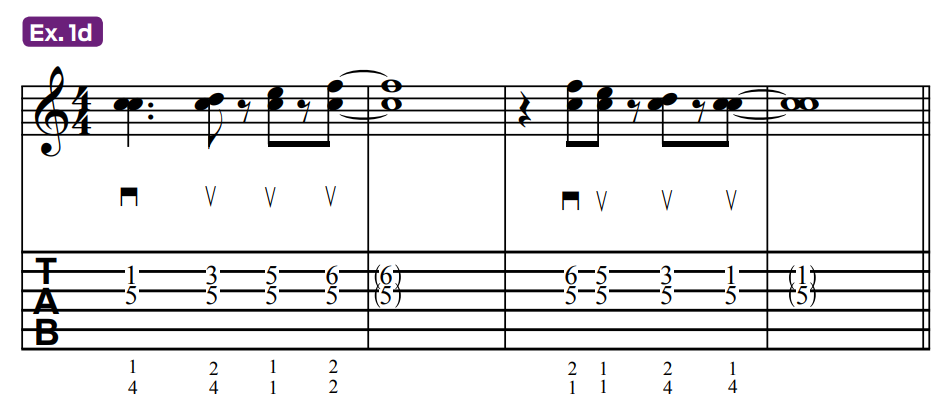

Ex. 1d demonstrates our fourth and final kind of harmonic motion, oblique motion, where one voice remains stationary, or static (stays on the same note), while the other moves up or down.

Here, both voices start on C, and as the top voice proceeds to move, the bottom voice stays planted on C throughout the entire line.

This kind of stationary note, whether reiterated or held, is often referred to as a pedal point, or pedal tone, particularly when the note is in the bottom voice, as it is here.

Effective voice leading incorporates all four of these types of motion, which can be used to craft a sense of melody weaving through a chord progression, rather than just moving the same block chords around.

So how does one break out of the block-chord box? By incorporating...

CHORD INVERSIONS

Chord inversions are essential to good voice leading, as they allow the voices of each chord to move as little as possible to the next chord’s closest available notes.

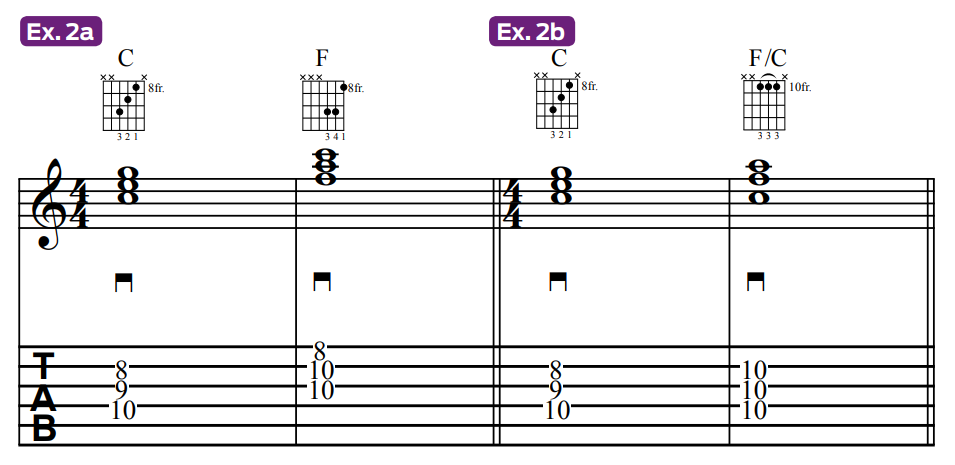

Let’s compare Examples 2a and 2b.

In Ex. 2a, we have a root-position (root on the bottom) C major triad (C E G) moving to a root-position F major triad (F A C).

Here, all of the voices are jumping, or skipping, up three steps, or scale degrees, resulting in a rather abrupt-sounding transition.

In Ex. 2b, we start on the same root-position C chord, but instead of going to the root-position F, we move minimally to a 2nd-inversion F chord, which puts the 5th of the chord, C, on the bottom (voiced, low to high, C F A).

This results in the root of the C chord staying put as a common tone when we change to the F chord, while the E and G notes move up by only a half step and a whole step, to F and A, respectively.

This is a smoother-sounding transition than in the previous example because the movement is restricted to stepwise motion, with no skips.

Now let’s look at a pair of examples inspired by the rhythm work of two of rock’s greatest guitarists, Eddie Van Halen and Randy Rhoads, who have often used these types of simple triad inversions and voice-leading approaches to create iconic riffs in songs like “Runnin’ With the Devil” and “Crazy Train.”

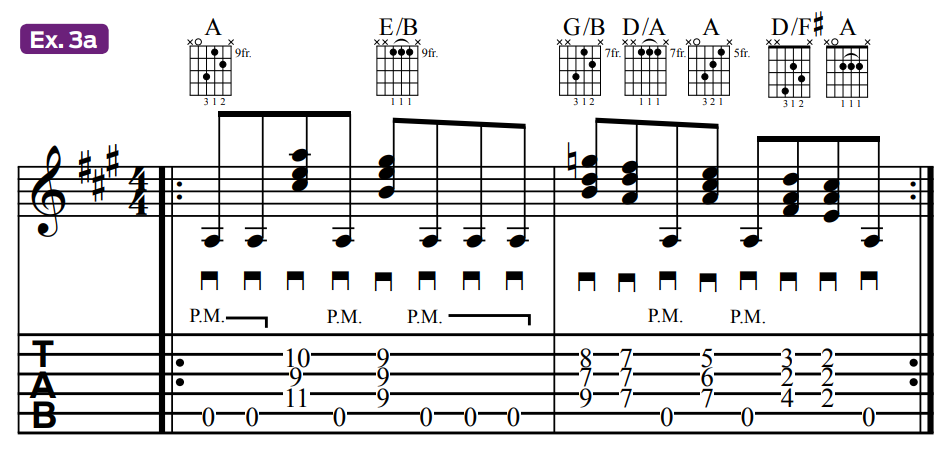

Ex. 3a shows a progression in the key of A major (A major scale: A B C# D E F# G# ), for which we will navigate a series of descending triad inversions on the D, G and B strings over an open A-string note, which will serve as a pedal tone throughout.

The first triad is A major in 1st inversion, with the 3rd on the bottom (voiced, low to high, C# E A).

Then we drop both the lowest and highest voices down one scale step, to B and G#, respectively, while the middle note, E, remains stationary, as a common tone, thus shifting to an E major chord in 2nd inversion (voiced B E G#).

After that, we have the same motion a whole step and two frets lower, moving from a 1st-inversion G chord (B D G) to a 2nd-inversion D (A D F#).

We then move to a root-position A chord (A C# E), followed by a 1st-inversion D (F# A D) and finally a 2nd-inversion A (E A C#).

Another common and musically effective approach to employ with voice leading in a progression is to arpeggiate the inversions, picking out the notes individually, which adds rhythmic and melodic interest to chord changes.

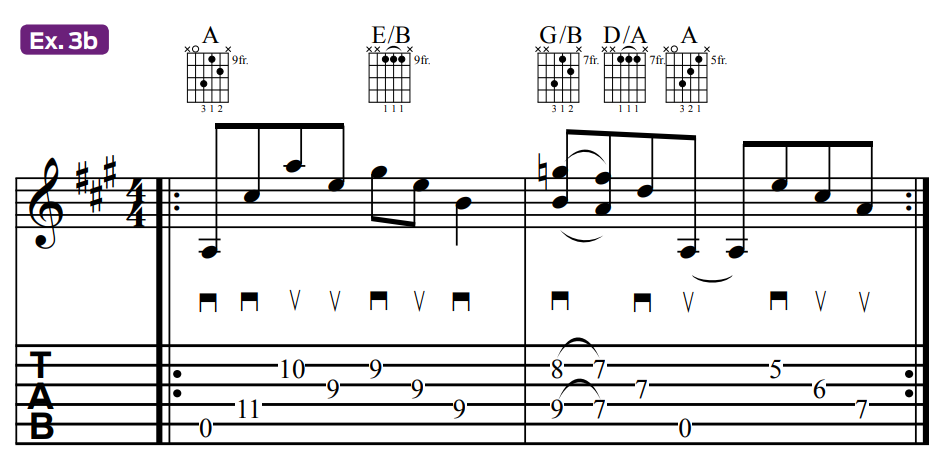

Ex. 3b takes the first five chords from the previous progression and breaks up each triad into ringing eighth-note arpeggios, which creates an appealing sound. (Try switching from a thick, distorted tone for Ex. 3a to a clean tone for Ex. 3b, to create a “chorus-to-verse” textural/ timbral contrast, as you would typically find in a rock guitar arrangement.)

In both examples, the descending triads move using a combination of similar and oblique motion. These triad shapes lend themselves well to these particular forms of motion because the notes are packed close together, making it more efficient and convenient to move some voices stepwise while others stay planted.

Now what if we want to apply contrary motion? We can do this by first introducing some wide intervals and open, or “spread,” voicings into the mix.

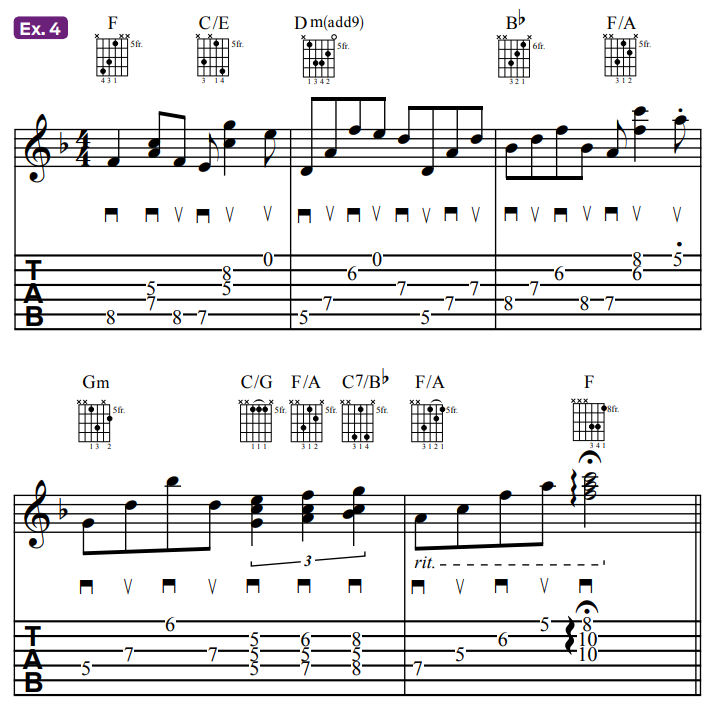

Ex. 4 uses both close-position triad voicings, wherein the root, 3rd and 5th of each chord are packed and stacked as closely together as possible, as in all of the previous examples; and open-position voicings, wherein one of the voices is moved up or down an octave, creating a gap and more space within the voicing, specifically an open 5th interval or larger, to build a greater sense of individuality, motion and interaction among the voices without having to move the entire triad up or down in an abrupt manner, as we had done in Ex. 2a.

We’ll start by playing a root-position F triad (F A C), voiced in close position. From there, we’ll move the F root note down a half step to E, then the A and C notes move up to C and G, respectively. This creates an open-position C triad in 1st inversion (voiced, low to high, E C G).

While the top two voices move up in similar motion together, they both move in contrary motion to the bottom voice, which descends.

The rest of the example proceeds in this manner, alternating between close-and open-position voicings to create good counterpoint (independent voices), while also adding and subtracting voices to build additional melodic tension.

You can also apply these voice-leading concepts to those big, open block chords that we’ve been shunning thus far.

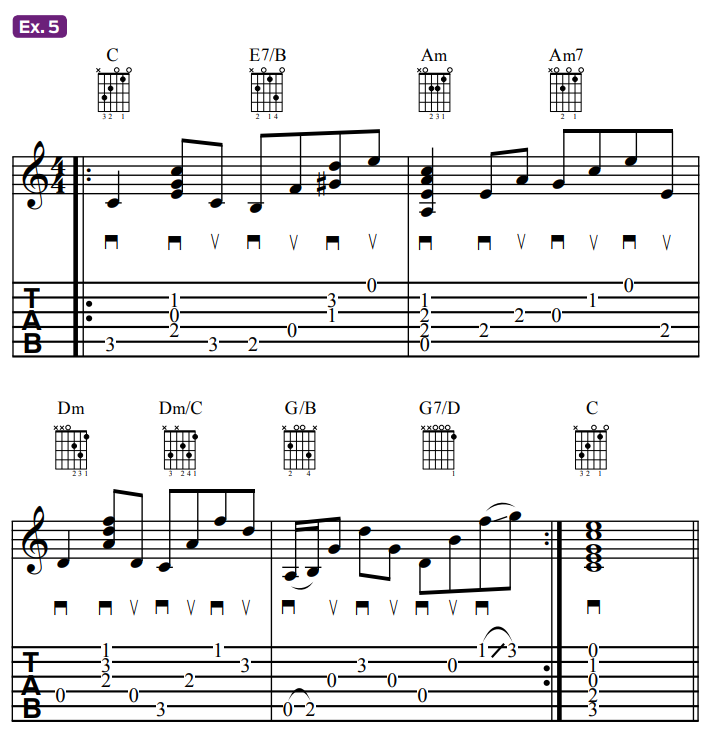

Ex. 5 uses common open chord shapes – specifically C, Am and Dm – in conjunction with inversions to liven up what would be a mundane-sounding progression if played with open block chords throughout.

Start by playing a standard open C shape on the middle four strings (voiced, low to high, C E G C), then transition to E7/B (voiced B D G# D E), with the bottom note descending while the two higher voices ascend, creating contrary motion.

The next bar moves to an open Am shape (A E A C), then to Am7 (A E G C). From there we transition to Dm (D A D F), then invert that chord by dropping the root down to the minor, of “flatted,” 7th, C, to create a 3rd-inversion (7th in the bass) Dm7/C (C A D F).

From there, we arpeggiate an open 1st-inversion G triad voicing (B G D), followed by a G7 chord (D B F), with the flatted 7th chord tone, F, sliding up to the G root.

Within this example, you can see how all of the moving parts kind of “ebb and flow” together to create interesting musical textures and a feeling of tension and release with minimal movement.

Now let’s take things to the next level.

CHORD EXTENSIONS

Chord extensions, also known as tensions, can be used to not only make chords sound more harmonically dense and interesting but also to create additional voice-leading opportunities.

This approach has most famously applied by jazz guitarists such as Joe Pass, Jim Hall and Kenny Burrell who blend melody and accompaniment, “chord-melody style,” but chord extensions can be applied in any stylistic setting.

The most well-known example of this idea in rock can be found in the intro to Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” in which Jimmy Page transitions from a root-position Am chord (voiced, low to high, A C E A) to Am-maj9/G# (G# C E B), then a 2nd-inversion C/G (G C E C).

While the middle voices, on the G and B strings, stay on C and E through all three chords, the top voice ascends the first three degrees of the A natural minor scale (A B C) while the bottom voice descends chromatically, from A to G# to G.

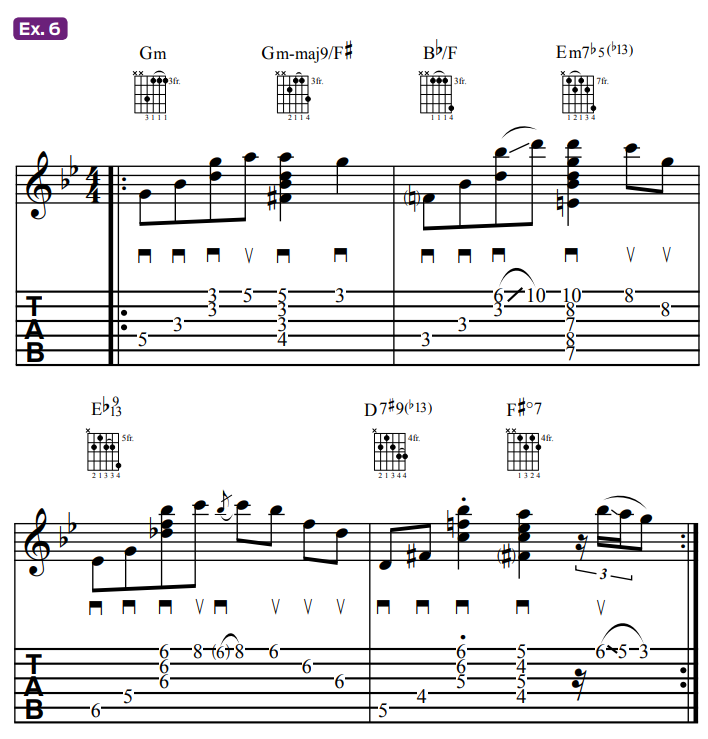

Ex. 6 presents a jazz-style take on this “Stairway” idea. Here we’re playing in the key of G minor (G natural minor scale: G A Bb C D Eb F) while incorporating a descending chromatic bassline (G F# F E Eb D) to contrast the scale tones used in the accompaniment and melody.

The first three chords mimic the contrary-motion of the “Stairway” intro, but after the 2nd-inversion Bb/F chord, we slide up to a root-position Em7b5 (voiced, low to high, E Bb D G D), with the melody incorporating the b13 tension, C.

In bar 3, we play Eb9 (voiced Eb G Db F Bb) with a 13 tension in the melody (the high C note again).

In the final bar, we move from D7# 9b13 (D F# C F Bb) to F# dim7 (F# C Eb A). Going back to the first two measures, notice that the bassline descends as the melody ascends, but the middle two voices remain in place on the notes Bb and D.

This trend, of course, changes in the final two bars, where we not only start to move these notes in a descending manner through the remainder of the progression – with the Bb moving down to G and ultimately F#, and D descending chromatically to Db then C – but we also add a fifth voice to increase the harmonic density.

And yet, for all of the harmonic complexity of this example, the voices never move more than a third. All the motion is kept primarily to either stepwise or static movement.

This is a worthwhile approach to keep in mind when crafting your own voice-leading progressions: Treat each voice as part of an interwoven melodic tapestry.

As one voice remains static, another can move more freely, and/or another voice provides counterpoint, and what have you.

Balance is key when creating your own voice-leading chord progressions. If all of the voices are moving around constantly and without taking melodic consideration into account, it not only defeats the purpose of voice leading – it also makes for a less interesting progression.

Try using all of the different types of motion presented in this lesson when venturing into voice leading, and be judicious, thoughtful and tasteful when moving your voices.

But above all, be creative and have fun!

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band