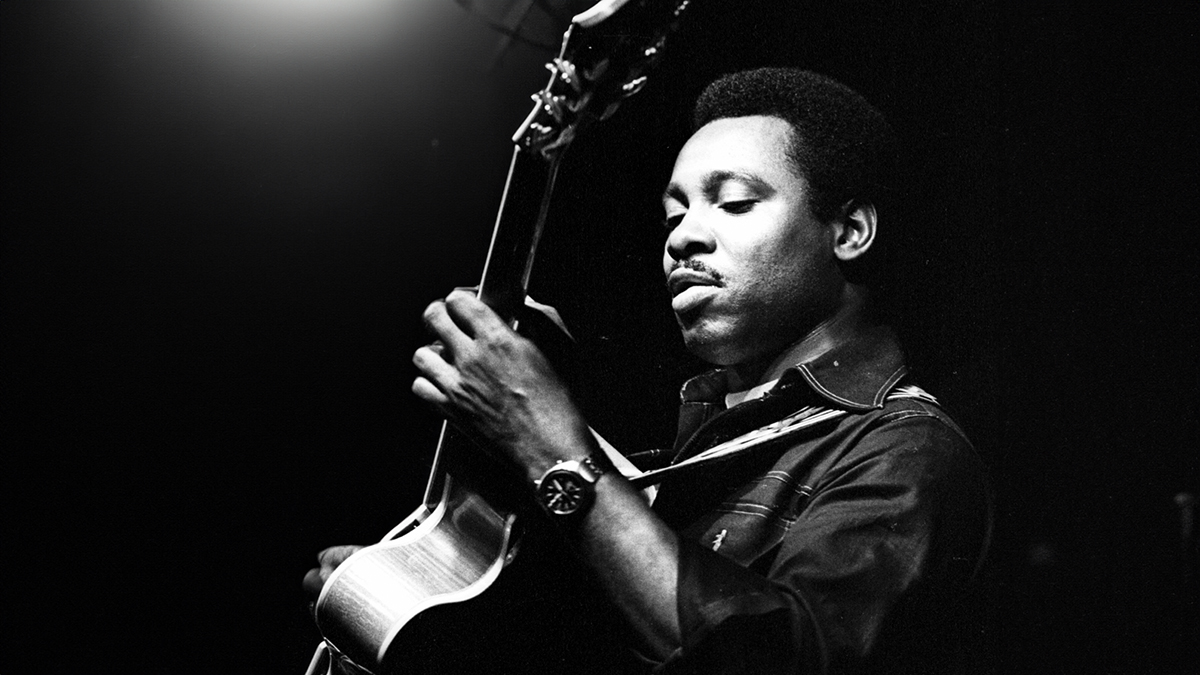

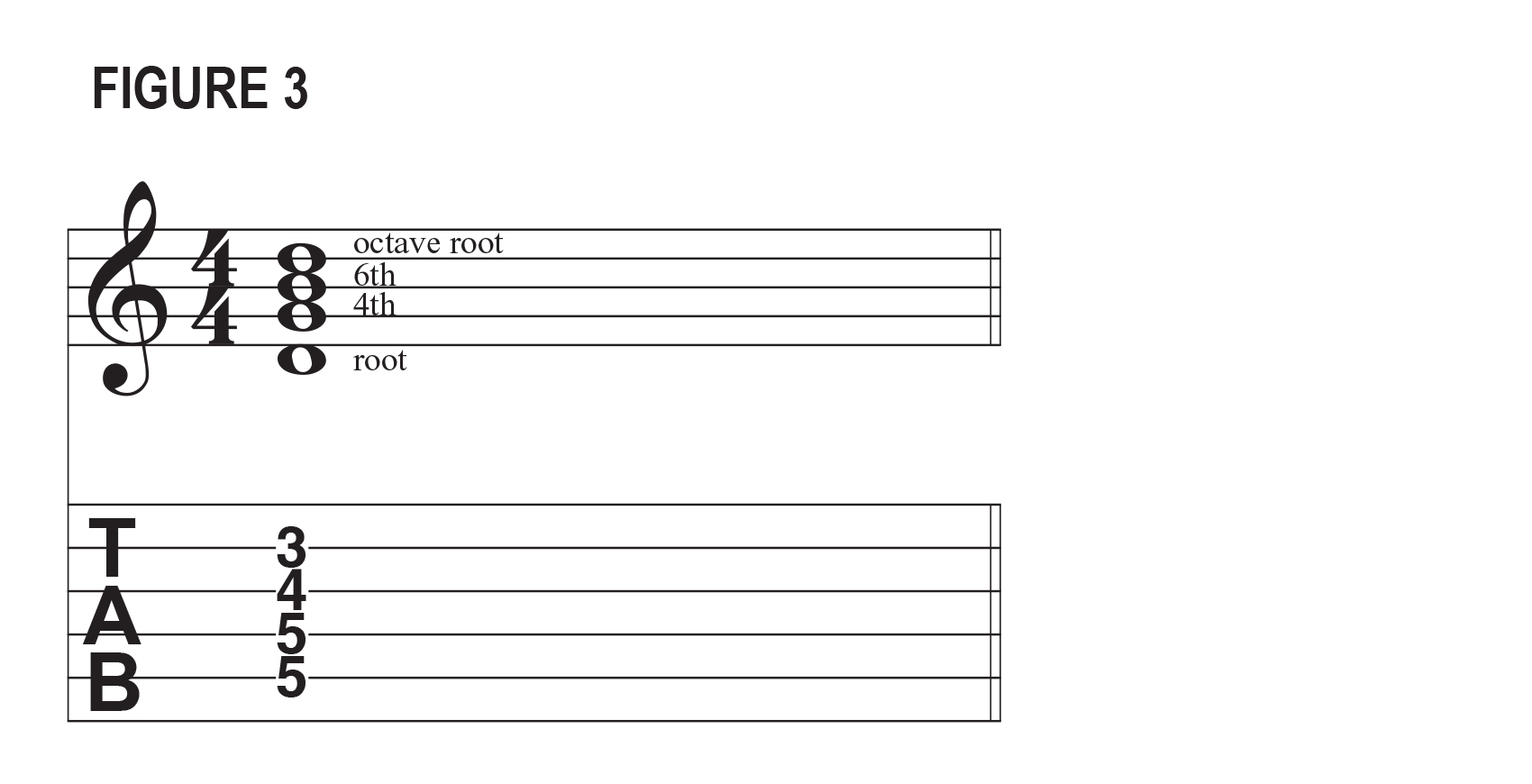

"I realized there was something in them very appealing to the listener. It's a richer sound." George Benson shows how he uses octaves in this lesson from Guitar Player's August 1976 issue

One of the most distinctive aspects of George Benson's soloing has been his use of octaves. Not since Wes Montgomery and Django Reinhardt has anyone utilized octave playing as extensively as Benson.

For Guitar Player's August 1976 issue, George was kind enough to share his approach to this tricky technique. His lesson and timeless advice are reprinted here.

My first encounter with octave solos was hearing a record by Django Reinhardt quite a few years before Wes Montgomery used them to any great extent. Django Reinhardt didn't dwell on octaves, but it was a part of his work. I started playing them immediately after hearing him use them. But to a great degree Wes Montgomery sort of mastered the octave concept. Plus he had a lot of finesse which gave it a much better presentation. I would imagine, since I came along after both of those artists, that I was more or less putting to use some of the things that they made available.

After recognizing their beauty and how octaves have a tendency to stick out, I realized that it was a good way to communicate. Since Wes gained such a wide popularity by using octaves, I realized there was something in them very appealing to the listener. It takes out the one-dimensional, thin sound and adds body to the electric guitar. It's a richer sound, because you're using the lower octave, which doesn't have quite the sharpness a higher note might have. This, I think, is comparable to the cornet as opposed to a trumpet — it's a much mellower sound, more pleasant to the ear.

I use octaves in several different ways, such as with chords, because sometimes by playing just octaves I feel my solo is very empty. I don't use them exclusively — I'm basically a single-line player — but when I want to add fullness, I'll use either octaves or certain formulas which use octaves.

Sometimes I'll take these formulas and play with them rhythmically, and that's when the fun starts. The octaves are tools from which I've derived a lot of different gimmicks to make them interesting and different from, say, those of Wes Montgomery or Django. I was very impressed by their uses of octaves — Wes using them in a very romantic and sentimental con- text that added a pretty side to even the funky things he played; and Django using them as a very dynamic interlude to what he was playing.

What I do with octaves began years ago when I heard a guy play this certain this formula, which consists of octaves and another note. I don't know if he played it accidentally or not, but I thought it was just gorgeous. I asked him to show it to me, and I always planned to use it one day.

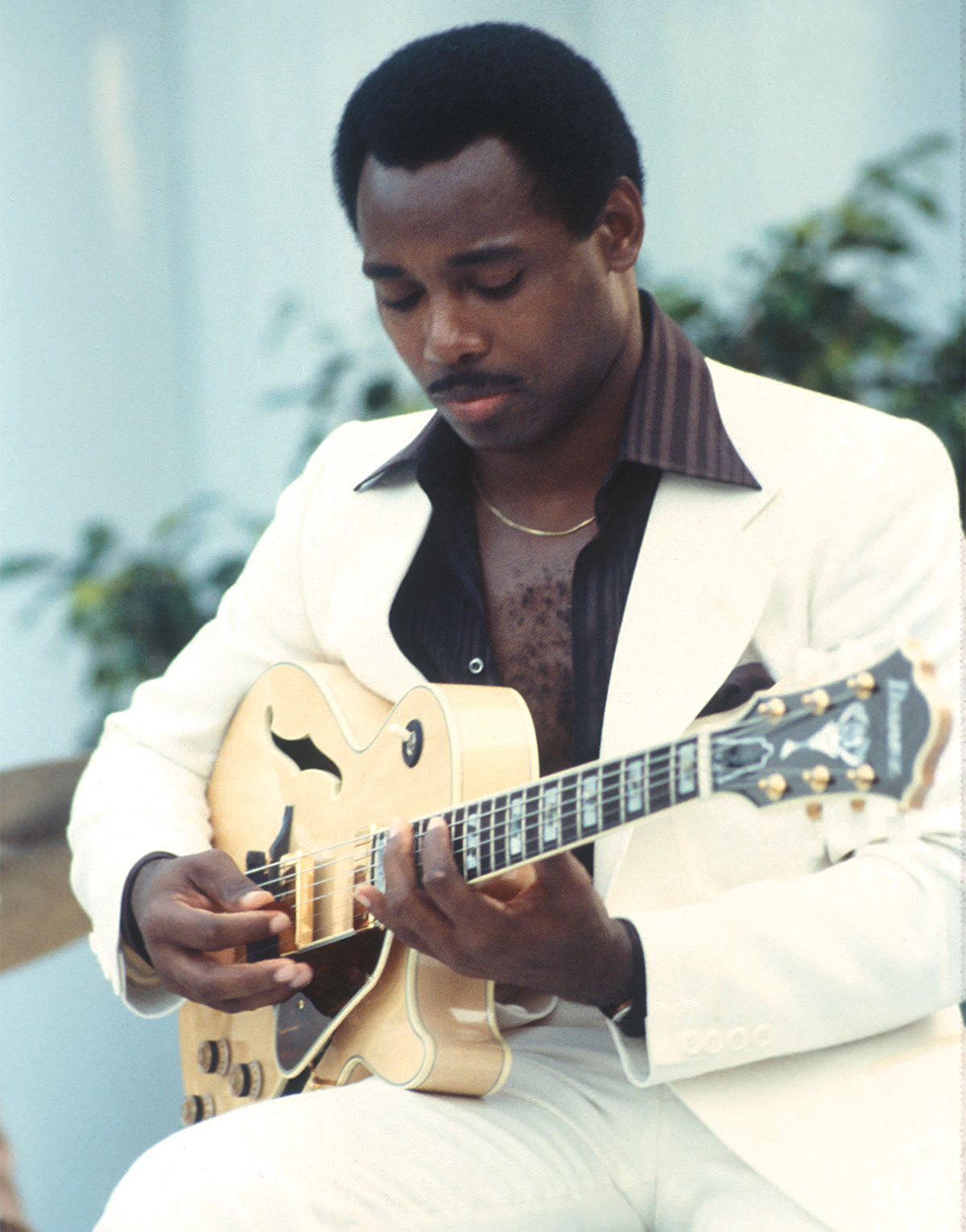

In involves the use of a 6th tone in addition to the octave. I may use a G with an E and a G an octave higher, and then the 6th tone would move in and out depending on the change of the chord. For instance, if I was going to play in G minor, and during the G minor scale I was going to use the A tone, I would use A, F, A. This involves moving or positioning my fingers a half-step closer on the inside—which is the 6th. But that's only one formula [Fig. 1].

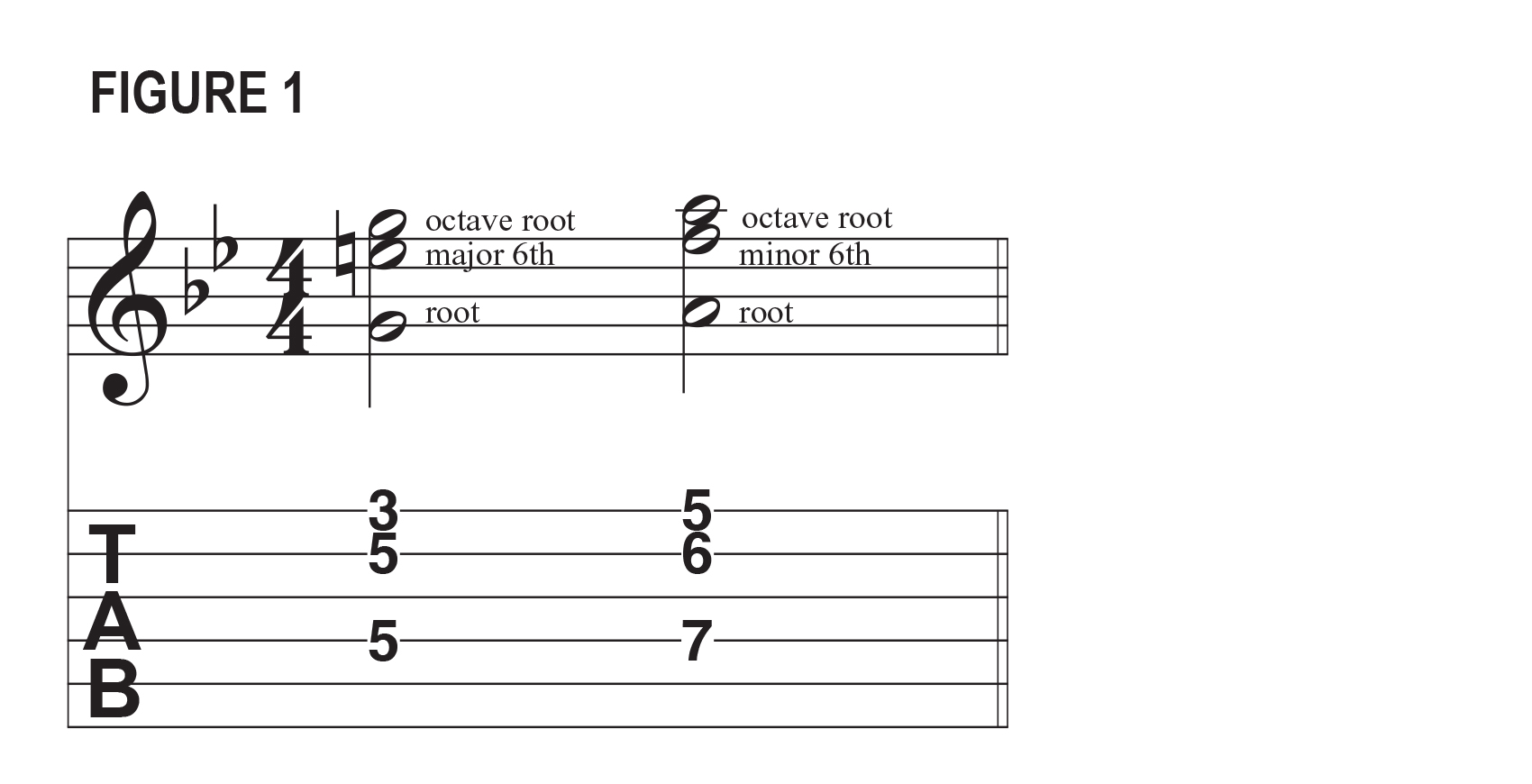

Another formula I use places the 5th and 4th in between the octave. I may play C, F, and C an octave higher to produce a certain sound, and that would also change positions as I change notes. To stay in context with the melodic scale, I might have to reposition the inside of the chord, which is the 4th, F, and change it to the 5th, G, in certain instances so that I don't clash with the harmony of things [Fig. 2].

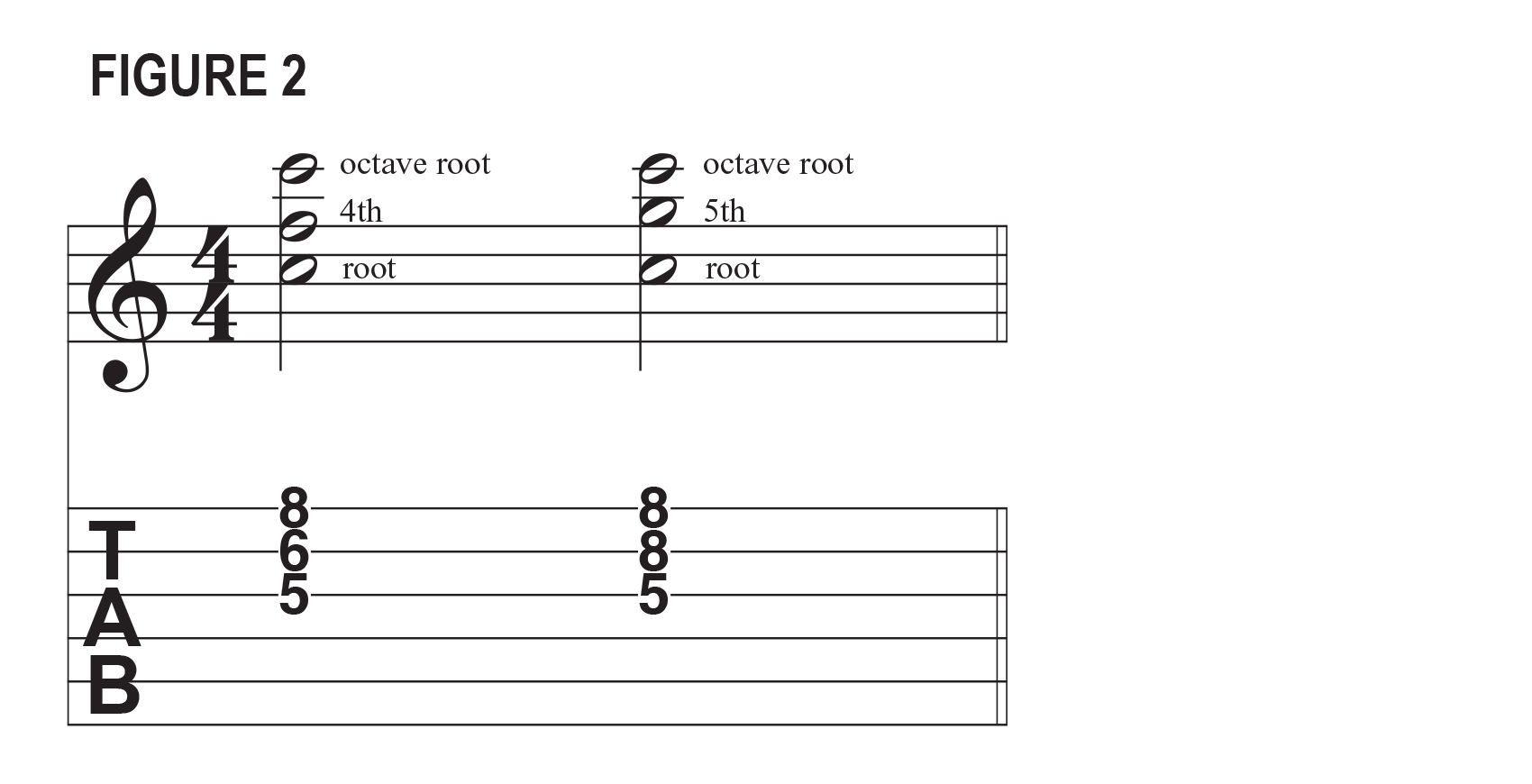

Then there's another form I've recently discovered that has a D as the first note, then the 4th (in this case G), a B and another D. So it consists of the root, the 4th, the 6th, and then the octave [Fig. 3].

I started experimenting with these forms rhythmically, where instead of playing the root and the octave simultaneously, I'd play them at different times. I'd play them against each other, and it would sound like octaves in rhythm. Also I'd drop the pick at certain times and use a shape with the 4th in it to get a sound similar to [jazz pianists] Fats Waller or Erroll Garner.

So there are many different things that can be done with octaves. They have a definite color of their own, different from anything else on the guitar, and their possibilities are unlimited.

Octaves really excel on guitar because of the characteristics of the instrument. They do for the guitar what a mute does for a trumpet. There's nothing like a good trumpeter, but sometimes the instrument has a tendency to become hard and unpleasant because of the characteristics of the notes that come out of it. They can get harsh to the ear, but the mute takes that harshness out and leaves that pleasant sound —that brass sound that isn't too brassy.

With octaves, the low note has a tendency to round off that high shrill note. When you play a high note on the guitar, it can be very obnoxious to the ear. But when you add the octave, it softens it up by becoming a compromise between the two, because you don't really hear either note, but rather something in between. It's like a marriage!

Octaves have been used in a variety of different lights since Montgomery first popularized them. They sound very good in the background, as a matter of fact. You can use octaves to add a soft backdrop behind singers or other solo instruments, where strings might be used. When you play them behind a singer, they add definition to the background music, as opposed to chords which leave the matter open of what the listeners might choose to hear. They can pick out any note in the chord to listen to, whichever note has meaning to them. But the octave eliminates that; it says this is the color I want, and this is what I want you to hear in the background, and this is what you're going to hear.

I use octaves intermittently wherever I hear a need for them. They're incidental within any given place. Some good examples would be "When Love Has Gone" from Body Talk, "No Sooner Said Than Done" off Bad Benson, and "So This Is Love" on Breezin'.

But with octaves you have to find your own way. Listen and learn as much as you can, but then put it to your own use. It's certainly worth putting a little time into, and I'm sure that when you get tired and run out of ideas playing single-line, you'll find freshness and comfort in the octaves

Dreamcatcher Events and Ibanez have announced Breezin' With the Stars – an immersive four-day event with George Benson.

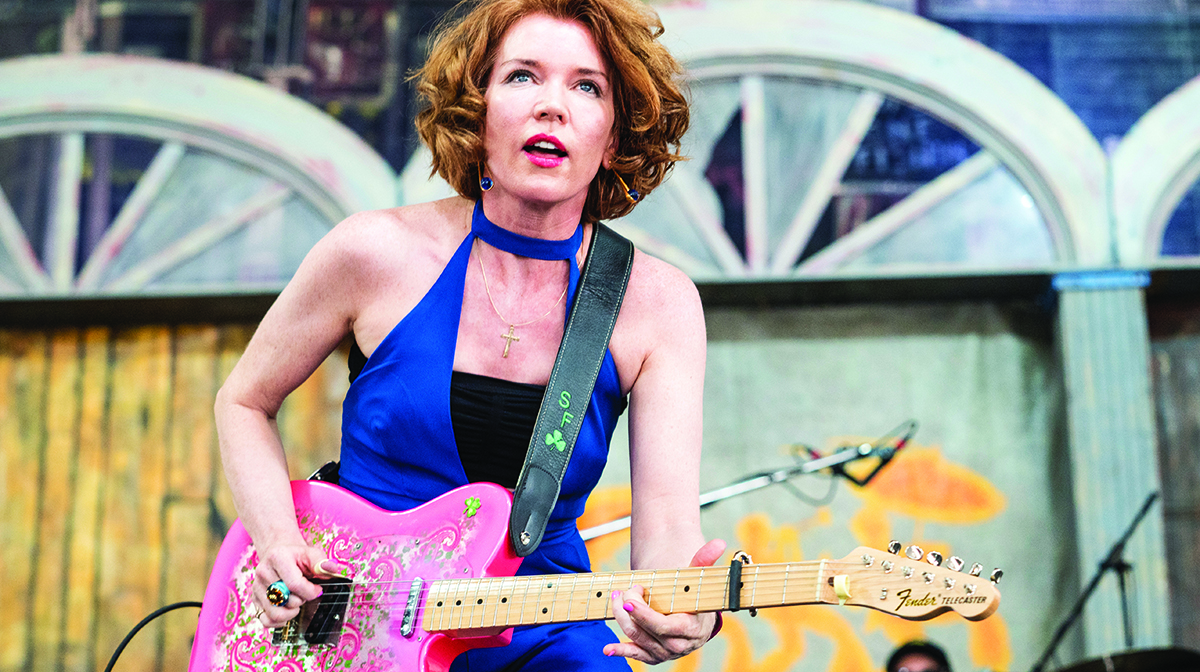

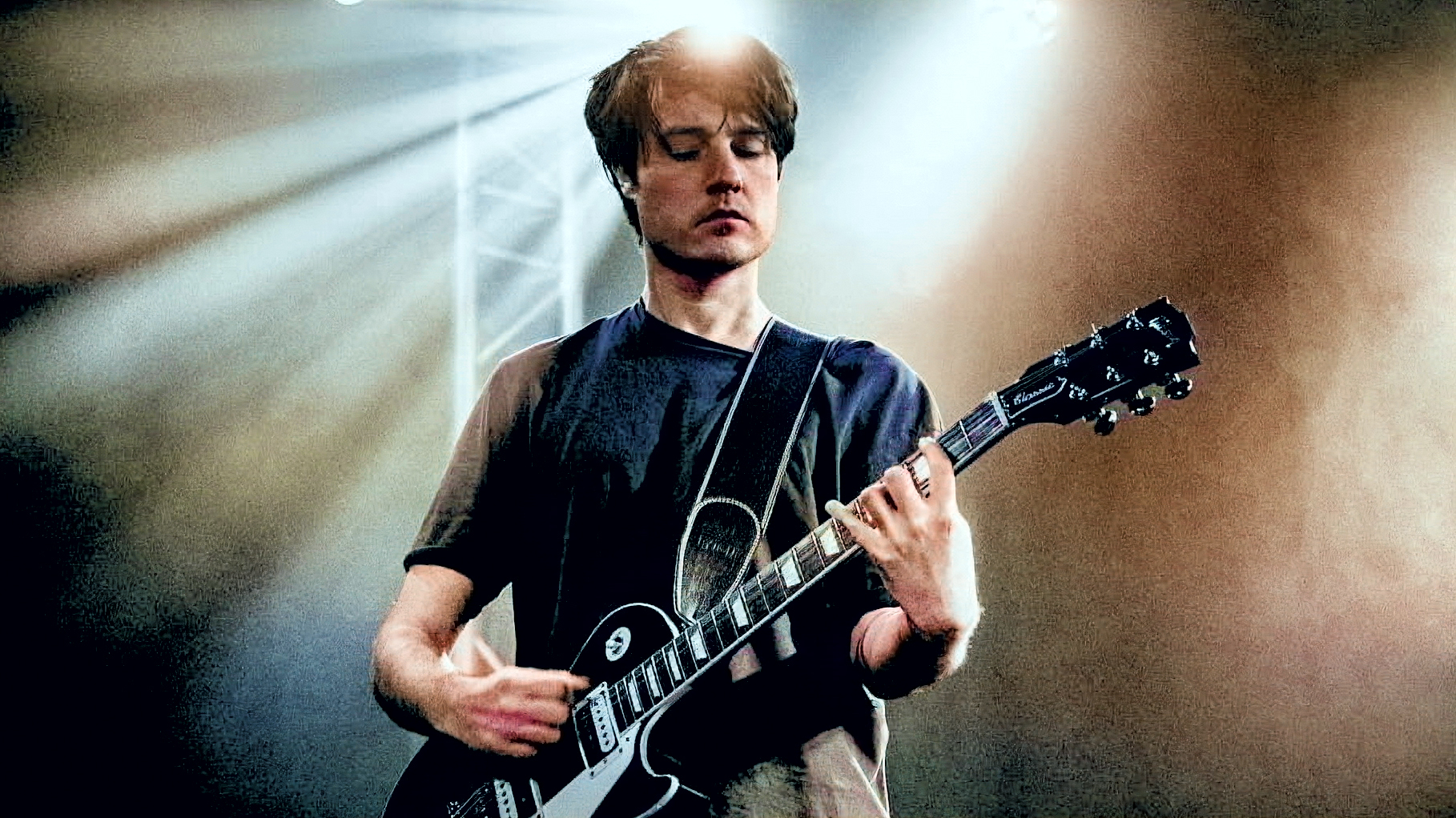

Taking place 3-6 January 2025 at the Wigwam Resort in Phoenix, Arizona, guests can rub shoulders with guitar greats including Steve Lukather, Cory Wong, and Tommy Emmanuel, alongside Benson, in an intimate but relaxed environment.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Launched in 1967, Guitar Player was the world's first guitar magazine and is now one of the premier sources of guitar news, interviews, reviews and lessons. When a story is credited to 'GP Editors', it means it's coming from the magazine team itself and that more than one of us has worked on the story.

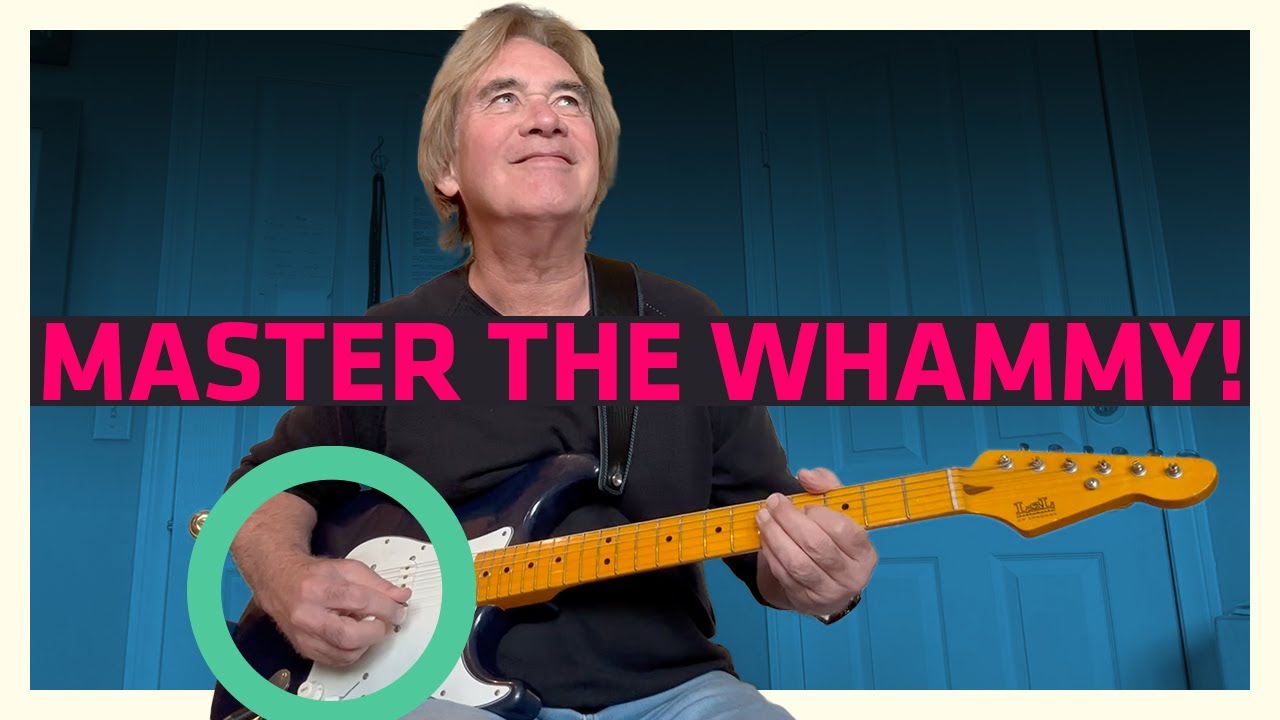

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band