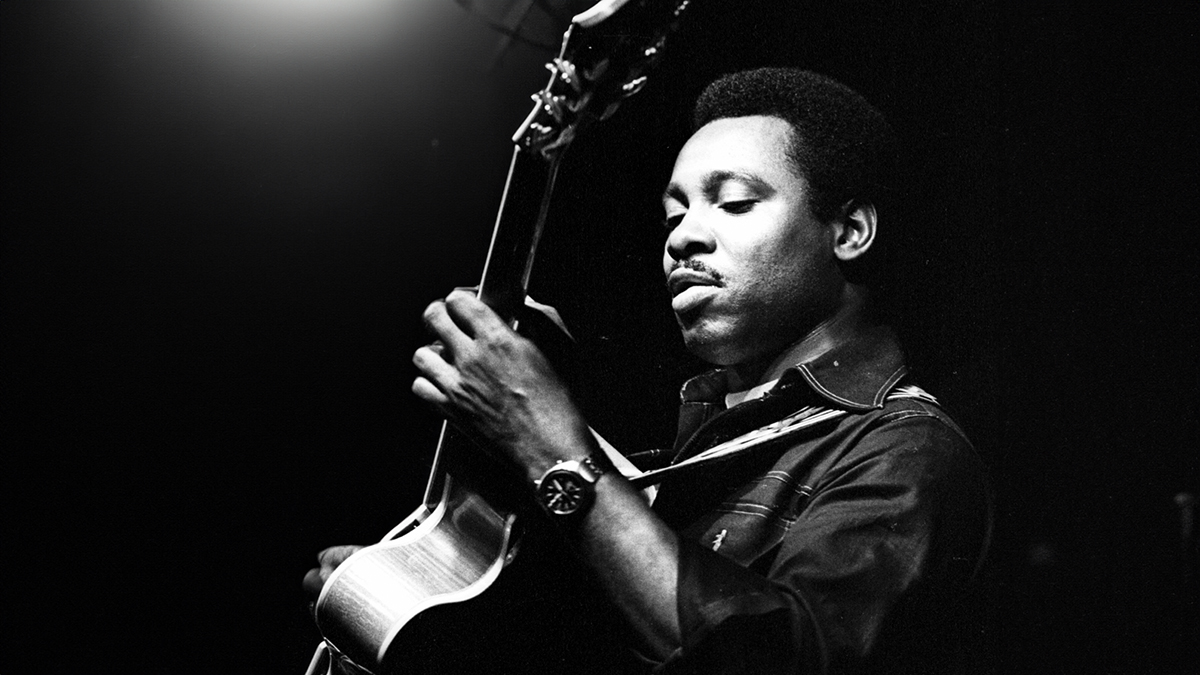

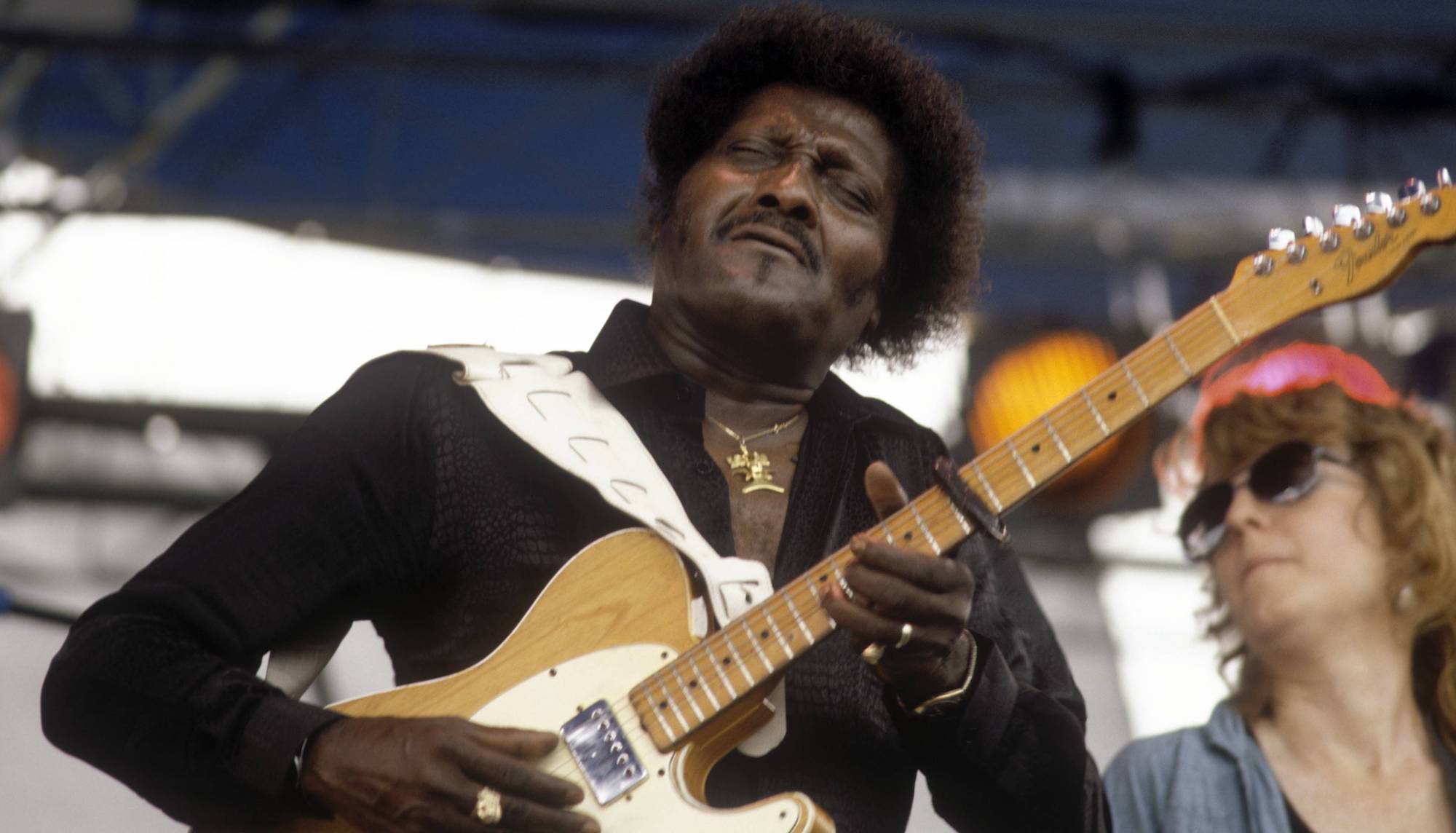

Follow the lead of players like Mark Knopfler, Albert Collins, and Lindsey Buckingham, and open the door to new techniques and textures, with this primer in fingerstyle rock guitar

Eddie Van Halen also incorporated fingerstyle to add another dimension to his playing, and so have modern virtuosos like Tim Henson, Lari Basilio, and Mateus Asato – learn how you can do the same

Generally, when we rock guitarists ponder adding a new technique to our arsenal, we find ourselves gravitating toward tackling a new and challenging way to negotiate the fretboard, or woodshedding a new picking technique. By the same token, when we have a hankering for new textures, we’ll often head over to YouTube to enter a rabbit hole of pedal demos.

There’s nothing wrong with exploring any of those options, but there’s a whole different palette of techniques and textures literally at your fingertips that you may have yet to explore. All you need to do is lay down your pick and visit the surprisingly ready-to-rock world of fingerstyle guitar.

But wait, you’re probably thinking, isn’t fingerstyle for acoustic guitarists? Yes, acoustic players most often find their way to fingerstyle at some point. But many rock guitarists – such as Eddie Van Halen, Tim Henson, George Lynch, Lari Basilio, and Mateus Asato – incorporate fingerstyle into their playing when desired. Others, like Mark Knopfler, Albert Collins, Lindsey Buckingham, Matteo Mancuso, and Richie Kotzen, do so exclusively.

You may also be thinking, ‘I already use hybrid picking from time to time, so I’ll sit this one out.’ And sure, hybrid picking – simultaneously or alternately playing notes with both pick and fingers – is a useful technique, with the benefit of leaving the pick readily available to use on its own.

One method is no better than the other, but I’ve learned that the more approaches you have in your bag of tricks, the more you’ll naturally find ways to incorporate them into your playing, leading you to discover new and exciting musical ideas.

So think of this lesson not as one designed to help you become a full-time fingerstylist, but rather one that opens the door to new techniques that will complement those you already have access to with your pick. Nothing can replace the pick’s sharpness of attack, not to mention the availability of pick (or “pinch”) harmonics and pick scrapes – all of which are fun quirks of the guitar few would choose to live without.

Let’s dip our toes into the fingerstyle waters with some examples based on familiar songs. There’s a lot to present here, so I’ve split this lesson into two parts. First, some housekeeping. As you’ll see in the musical examples presented here, in the same way that fret-hand fingers are indicated with numbers, pick-hand fingers are traditionally assigned a letter based on the Spanish words for the various digits:

p (thumb), i (index), m (middle), a (ring)

The letter c indicates the pinkie, but it’s not often used, so we’ll steer clear of it for our lessons, though it’s interesting to note that jazz guitar legend Joe Pass, who was predominantly a fingerstylist, would occasionally employ his pinkie to sound five-note chord voicings.

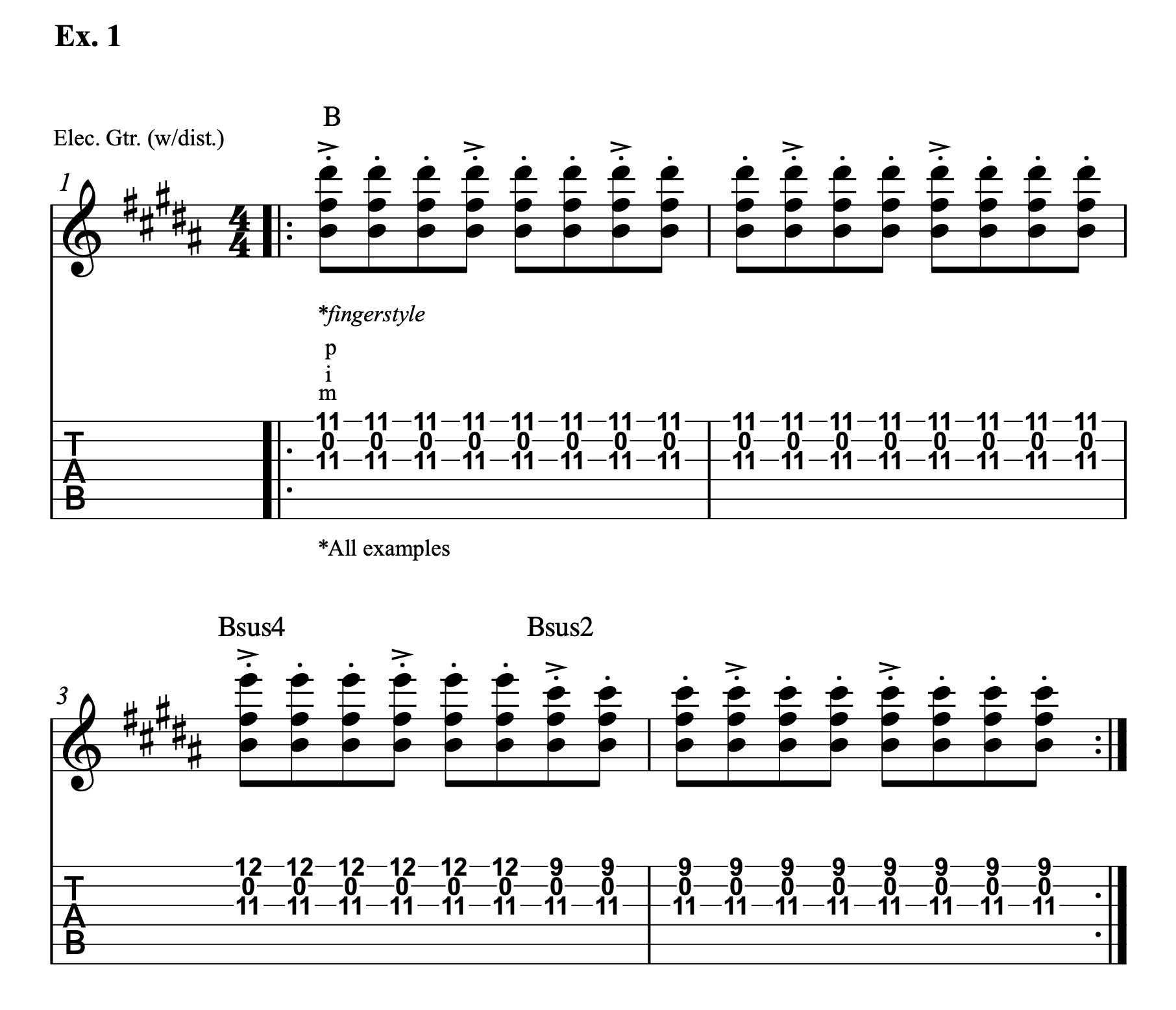

Now let’s get to the good stuff, beginning with one of the simplest fingerstyle techniques: playing a group of notes simultaneously, as if you’re banging out a chord on the piano.

In the classic AC/DC song For Those About to Rock (We Salute You), rock icon Angus Young uses hybrid picking to perform a nifty unaccompanied intro, and we’ll take the same approach but apply it sans pick. (We’ll explore a benefit to freeing up your thumb a bit later.)

Ex. 1 is based on Young’s earworm of an intro, and the key to making it sound just right is to play each eighth-note chord staccato, or short. To explain, first try playing this phrase with a pick. Note that you can successfully play the fretted notes staccato by lifting up your fretting fingers, but the pesky open B string just keeps ringing.

Next, let’s try it fingerstyle, shortening the notes by allowing your picking fingers to quickly rest on the strings before re-plucking them (no need to lift your fingers off the fretboard this time). More than being an effective way to mute the strings, this technique delivers a unique and particularly snappy attack. And it works equally well even if no open strings are involved.

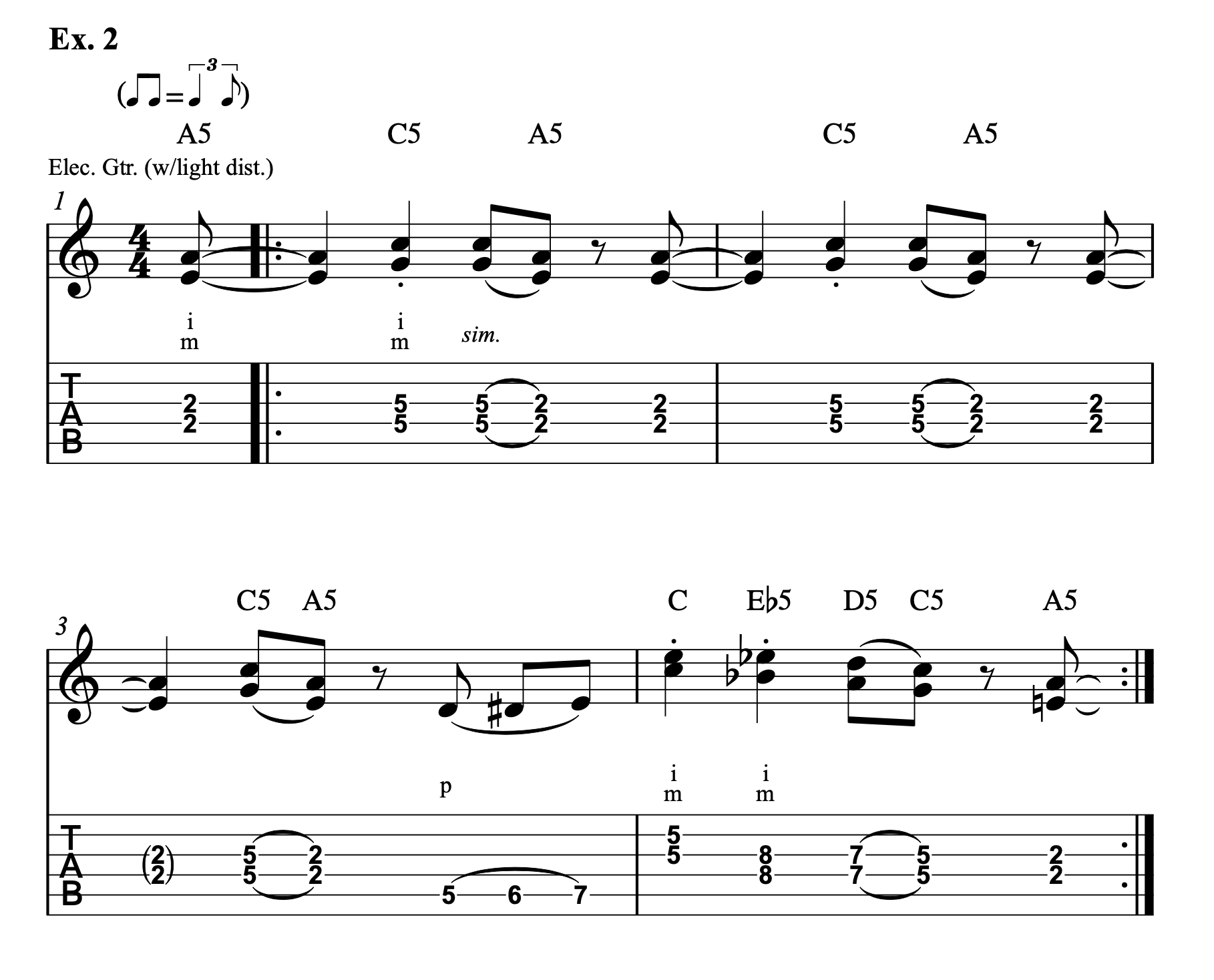

Next, let’s focus on developing our picking fingers so that they can function independent of the thumb.

The interval of a perfect 4th (two and one half steps) is integral to playing rock guitar – think of Ritchie Blackmore’s classic riff to Smoke on the Water. Ex. 2 takes a similar tack and is based on Van Halen’s Hot for Teacher opening riff. Let your thumb sit this one out, using your index and middle fingers to pluck each dyad, or two-note chord, with the motion coming solely from your fingers.

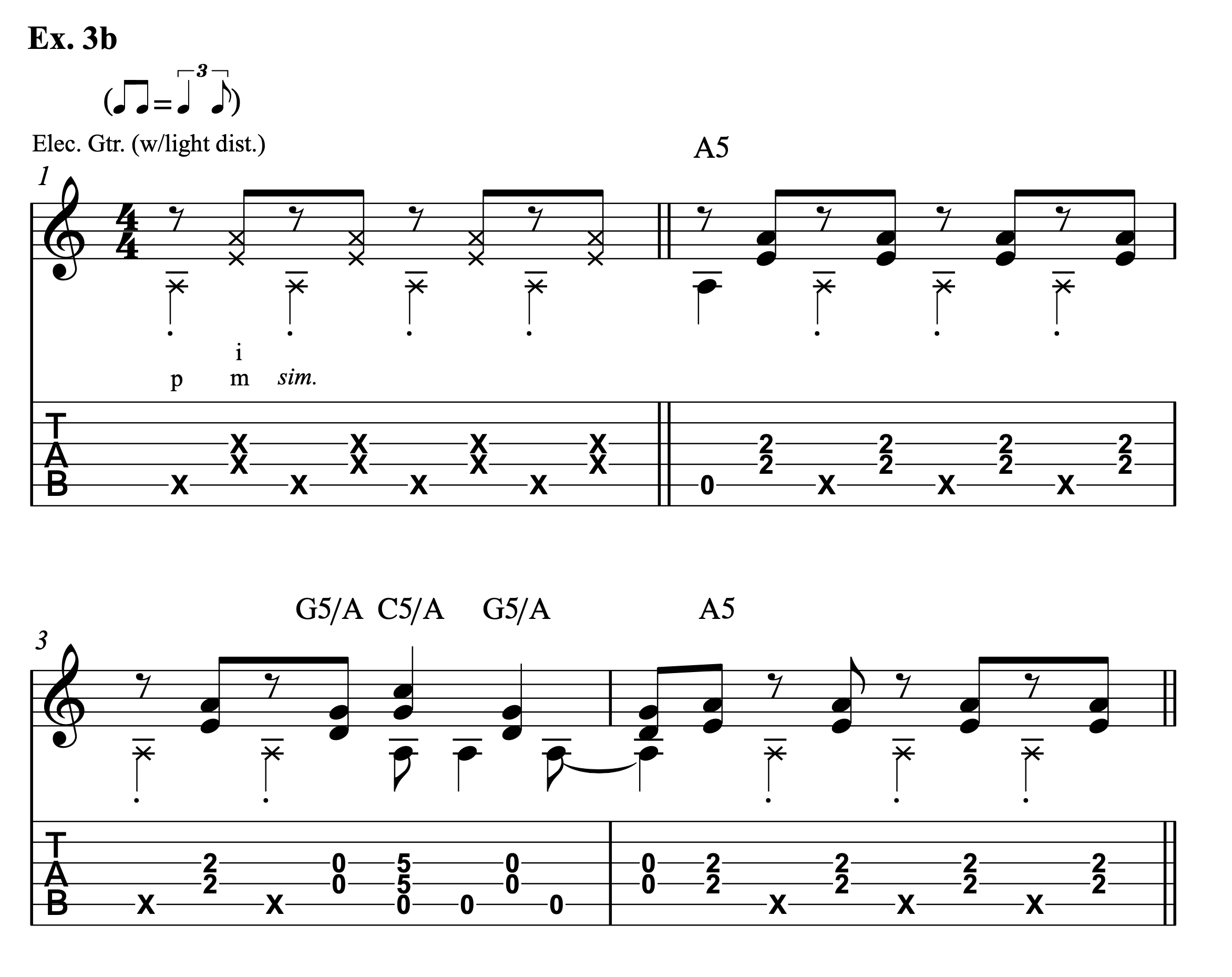

Fingerstyle guitar music is often notated using opposite stemming, as this allows two independent melodic or harmonic voices to be clearly shown and visualized for the reader. Up-stemmed notes are generally played with the fingers, and down-stemmed notes are most often played with the thumb.

Ex. 3a presents our first taste of opposite stemming, and while it sounds a bit more like an exercise than the previous examples, it’s simply a means to an end, as you’ll see in Ex. 3b. A helpful way to begin tackling Ex. 3a is to simply play only the downstemmed notes, using your thumb to play the open A string in a mostly quarter-note rhythm.

Once you start feeling comfortable doing that, begin incorporating the up-stemmed notes on the upbeats with your index and middle fingers. The key here is to let the voices ring over each other, as indicated by the notated rhythms. Played with a swing, or shuffle, feel, it’s reminiscent of ZZ Top’s La Grange, but it’s somehow lacking the charm.

Ex. 3b is where the magic starts to happen. Ostensibly the same musical idea as Ex. 3a, this phrase introduces muted notes, accomplished here by lifting your fret-hand fingers so that they lightly rest on the strings, effectively deadening them. Another helpful way to approach new fingerstyle concepts is to take your fretting hand out of the equation by sounding only muted notes, as indicated in bar 1.

First, let’s use the same technique as we did in Ex. 3a, plucking all of the deadened notes. Now, let’s take things up a notch: Instead of plucking with your thumb, lightly slap the lower strings with the outer portion of your thumb. After doing so, pluck the higher strings by rotating your wrist instead of flexing your fingers.

Now we’re on to something! Once you start to feel yourself grooving, begin to incorporate the fretted notes, as indicated in the final three bars. But note that while the down-stemmed muted notes are slapped, the standard open A notes are plucked, as in Ex. 3a.

This slapping technique is one of the new textures you’ll discover by playing without a pick. Note how the mix of techniques creates a means to becoming musically expressive in new and different ways, which is our ultimate goal here.

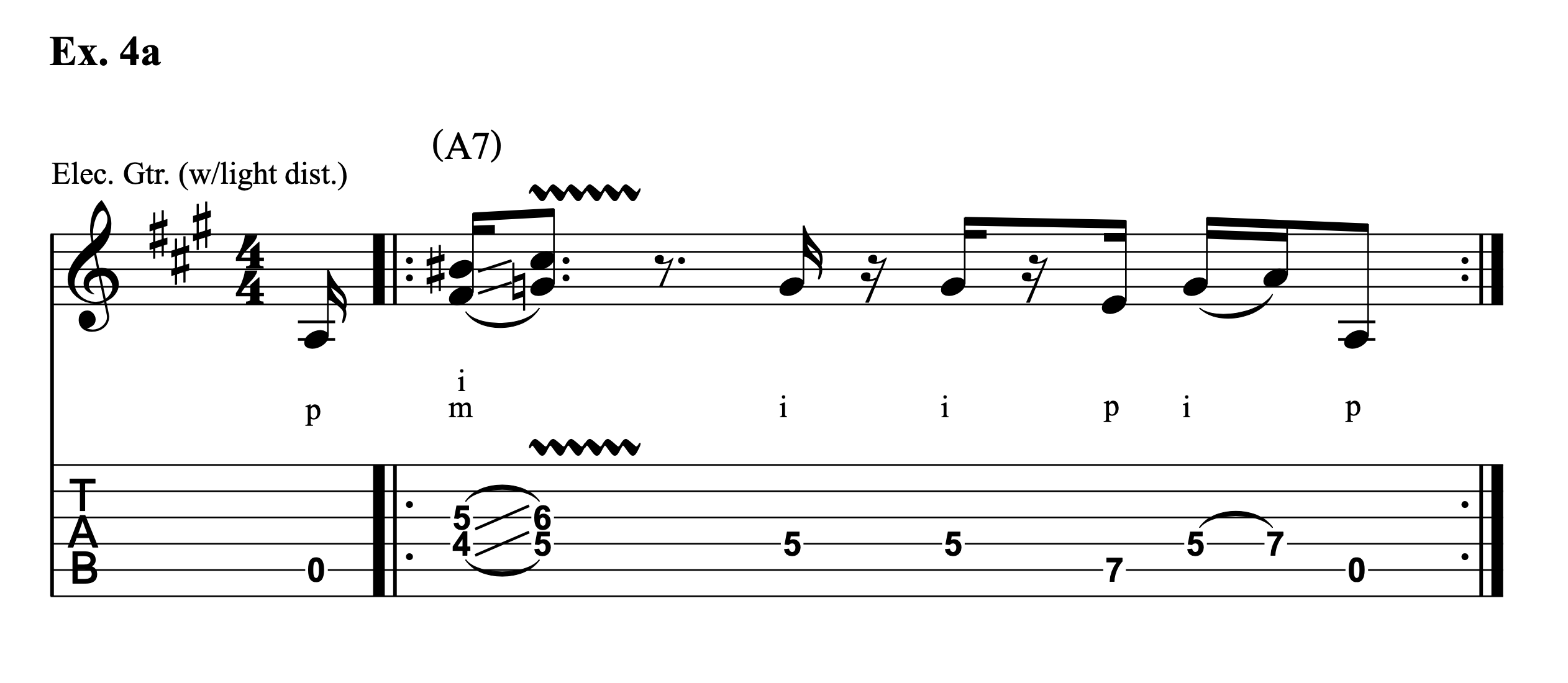

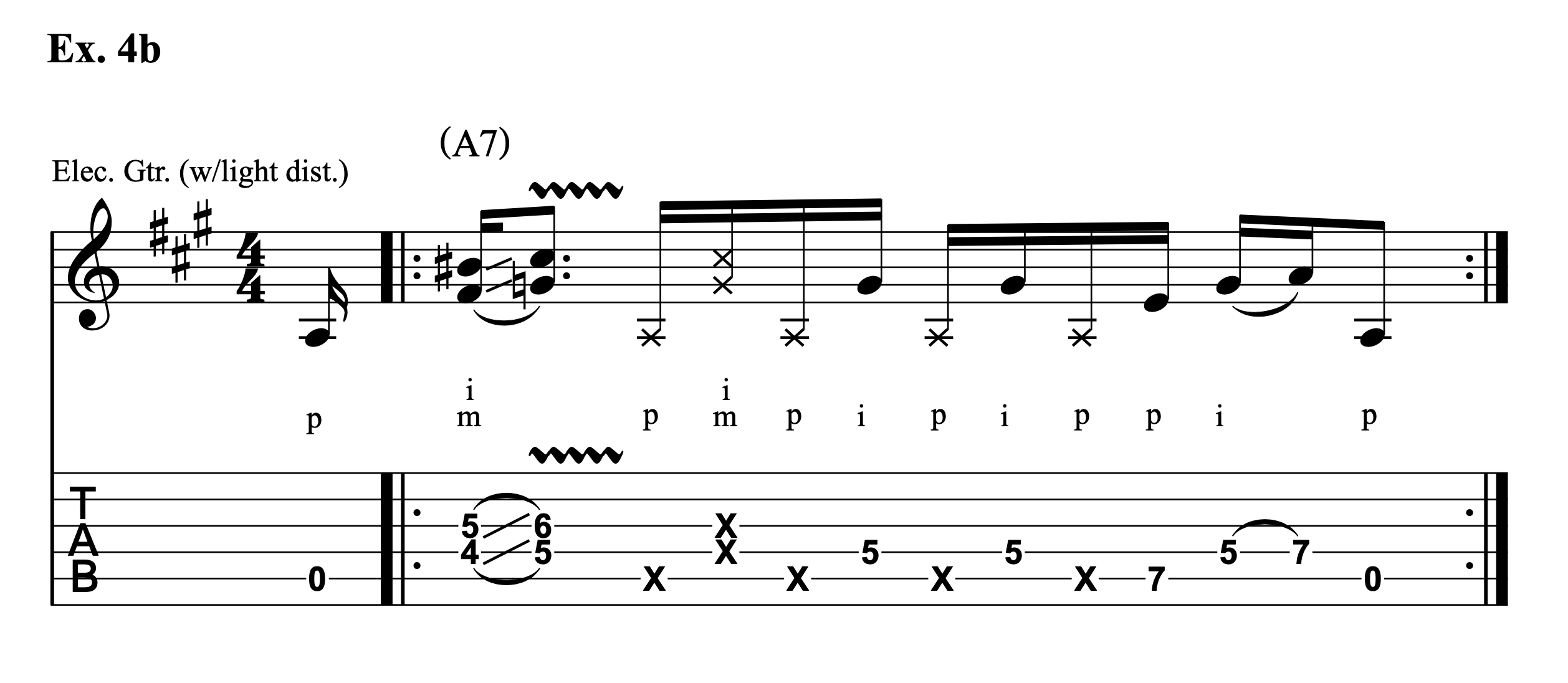

Next, let’s demonstrate this in a different way, using a phrase that sounds as if it’s a mash-up of Extreme’s Get the Funk Out and James Gang’s Funk #49.

Ex. 4a simply indicates the notes to be played, meaning it hasn’t yet been “funkified.” Once you’ve got the riff under your fingers, check out Ex. 4b, which adds the necessary funkification, by again incorporating muted strings using the slap-and-rotate technique from Ex. 3b.

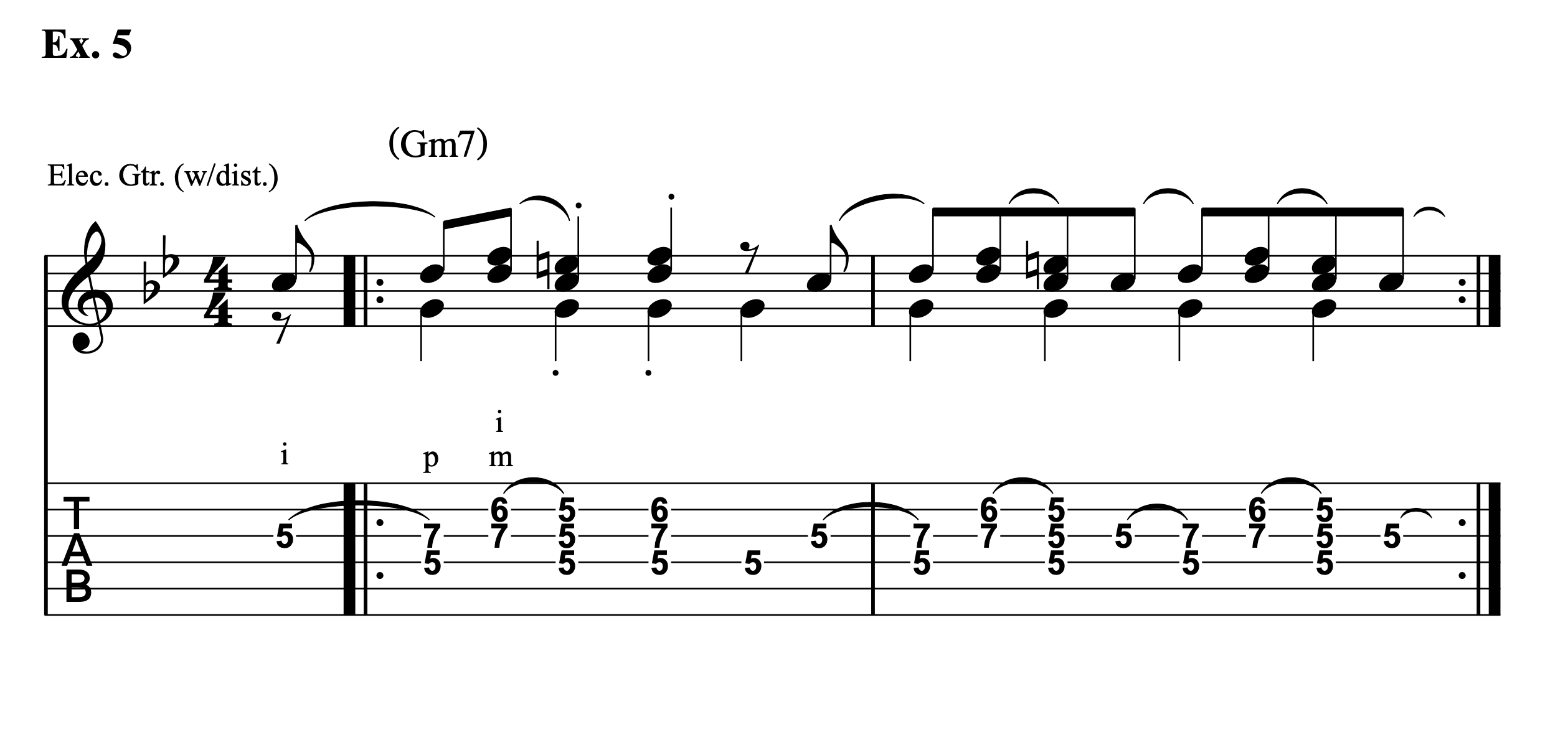

Now, let’s move on to a phrase that is challenging in a completely different way. Reminiscent of Mark Knopfler’s classic opening riff to Dire Straits’ Money for Nothing, Ex. 5 incorporates hammer-ons and pull-offs. But the main challenge here is to simultaneously play the thumbed down-stemmed notes with the hammered or pulled notes. We’ll be using the traditional plucking method from Ex. 3a.

Let’s start by simply playing, at a slow tempo, the initial pickup note, followed by the first dyad of bar 1. Tricky, right? This is just one of the hallmarks of Knopfler’s playing, and it might take a bit of getting used to, so begin slowly and please be patient. If it seems difficult, just know you’re on the right track.

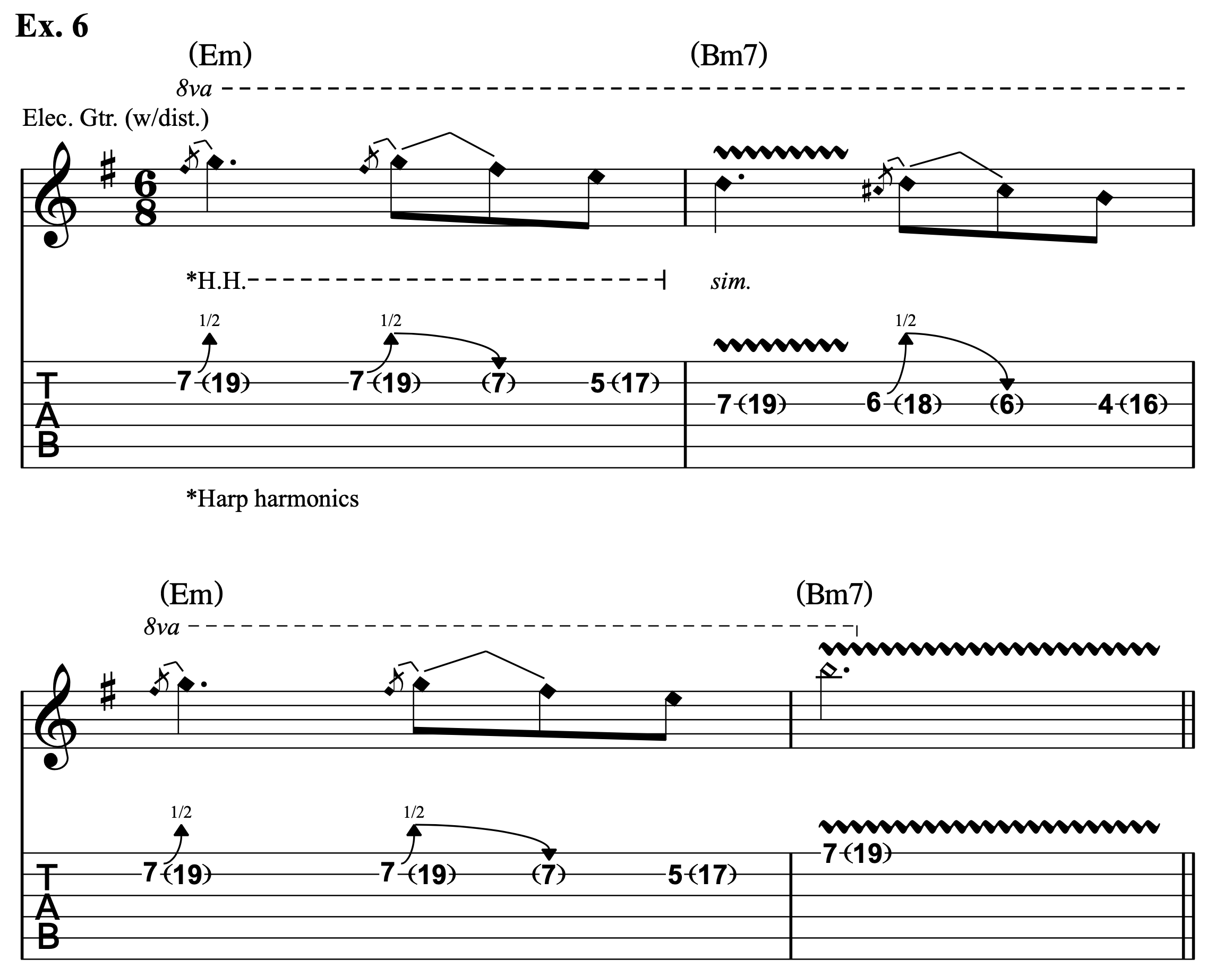

And now for something completely different! A harp harmonic is sounded by fingerpicking a fretted note while simultaneously touching the string very lightly with the tip of your pick-hand index finger 12 frets higher. The result is a harmonic one octave above the fretted pitch, which is not heard. (This is comparable to the way you don’t hear the open string when performing a natural harmonic.)

Players like Steve Morse will accomplish this by holding the pick between the middle finger and thumb. But playing fingerstyle can make these harmonics even more accessible, by allowing you to pluck downward with your thumb – or upward with your middle finger. (Note that using the thumb is more traditional, and you’ll need to execute them this way to tackle the examples in the upcoming second part of this lesson.)

Ex. 6 is a Celtic-flavored melody inspired by Morse’s elegant instrumental Highland Wedding, featured on his album High Tension Wires. Next to the initial tab number indicating the fretted pitch you’ll find another number in parentheses, which indicates the fret above which you are to lightly touch the string.

Just as you would with natural harmonics produced with open strings, be sure to touch the string directly over the fret to correctly target the harp harmonic. Also, be sure to dial in a considerable amount of overdrive and, if available, a compressor, both of which will make the harmonics more audible.

Fingerstyle players such as country icon Chet Atkins, who invented harp harmonics, and jazz legend Lenny Breau incorporated the technique into their playing in surprising ways, as we’ll see in part two. So spend some time in the woodshed, as it will be well worth it for our final installment!

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar lessons and custom transcriptions, feel free to reach out to Jeff on Instagram @jjmusicmentor or visit his website.

All examples © copyright 2023 Gilber Gilmore. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band