The Essential Eddie Van Halen Guitar Lesson

Learn the secrets of the guitar legend's trademark soloing style

This lesson originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Guitar Player.

Ever since I can remember, my mega-Italian mother, Mary Buono, has prepared a mystical grain pie for Easter, the recipe for which is to be kept secret at all costs. It’s the stuff of legend. Anyone who’s lucky enough to have had a taste speaks of the pie with reverence.

While Mother Superior is adamant about keeping the formula classified, in true Italian matriarchal fashion she is always more than generous with the dish, wasting no time putting a plate in front of you for you to enjoy. Edward Van Halen’s innovative and exciting lead guitar playing has had the same kind of presence in my life, and in countless others’ too.

Like my mom, he guarded his secret recipes by literally turning his back on live audiences during some of his most celebrated lead-playing sleights of hand, and often told tall tales in interviews when asked about his playing techniques and tone-creation process.

While much has been revealed over the years by both a more forthcoming Eddie and people who have astutely transcribed and analyzed his playing, some facets of his techniques still fly under the radar.

In this lesson, I’m going to take a cue from mom and serve up a plateful of EVH’s signature soloing techniques and concepts, with plenty of examples. Even better, I’m going to key you in on the musical ingredients.

Ed was a wizard at utilizing simple tools to create memorable riffs with clever approaches. Consider his use of natural harmonics.

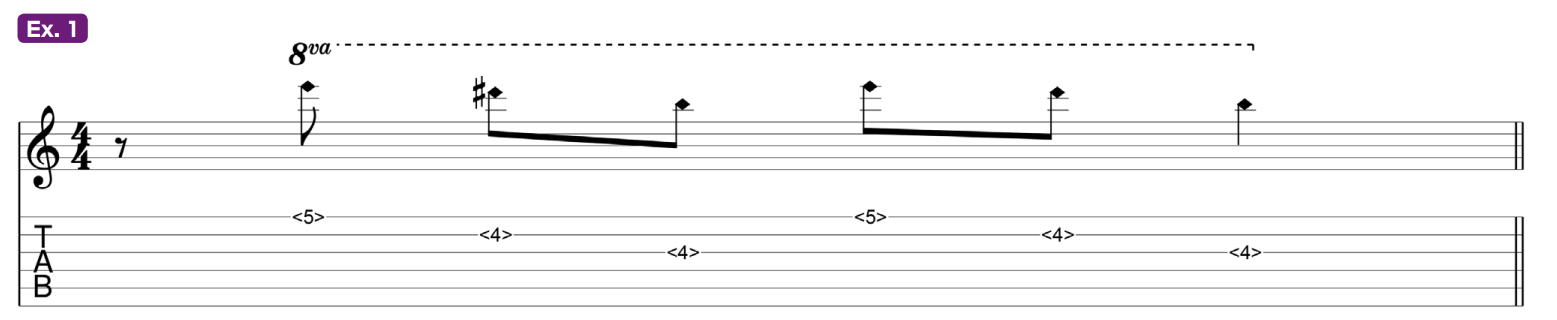

Ex. 1 opens the door with a taste of what he plays as part of the main intro riff in “Panama” (1984). The lick infers a timeless melodic sequence by way of a descending Badd4 arpeggio.

Ed makes it happen using a combination of fifth- and fourth-fret natural harmonics, facilitated by a light, precise touch and that glorious high-octane tone.

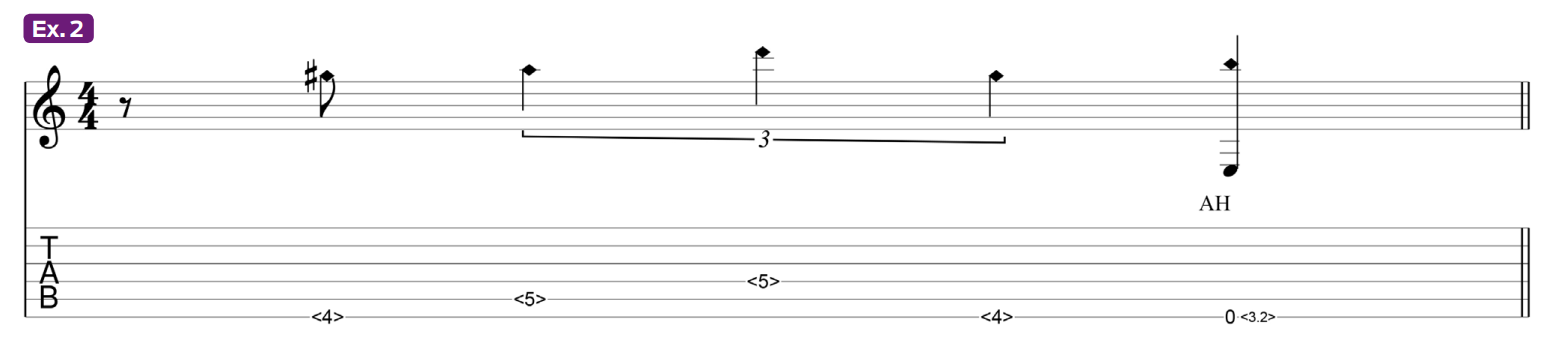

Flipping down to the lower strings, Ex. 2 is reminiscent of the latter half of the call-and-response verse riff in “Poundcake” (For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge).

To get that high B harmonic heard two octaves plus a perfect fifth above the open low E note, he lightly and precisely lays a fret-hand finger on the string just in front (not on top) of the third fret.

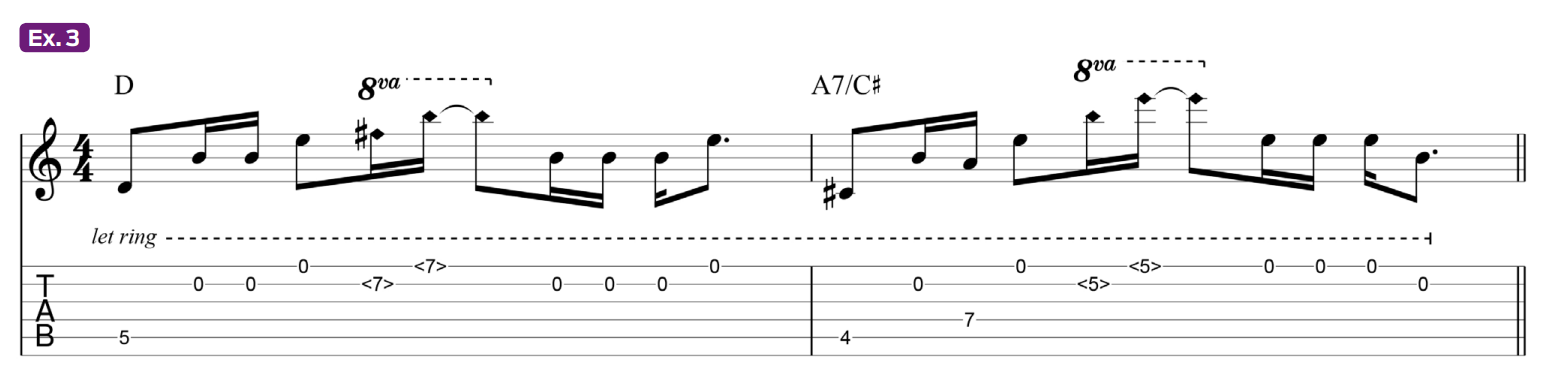

Ex. 3 is inspired by the opening of “Women in Love” (Van Halen II), where Ed nests natural harmonics within an open-string-based arpeggio idea. His use of natural harmonics doesn’t end with composed riff ideas.

Throughout the Van Halen catalog, there are myriad moments where he plays off-the-cuff licks with harmonics in classics such as “Running With the Devil” (Van Halen), “Mean Street” (Fair Warning), and “Hot for Teacher” (1984), to name a few. It goes without saying that Ed had amazing chops, and many admiring rock and metal guitarists assume they’ll never attain his level of technical fluidity.

Nevertheless, upon close examination of it, you’ll discover a collection of methods to his musical and technical madness that may give you hope.

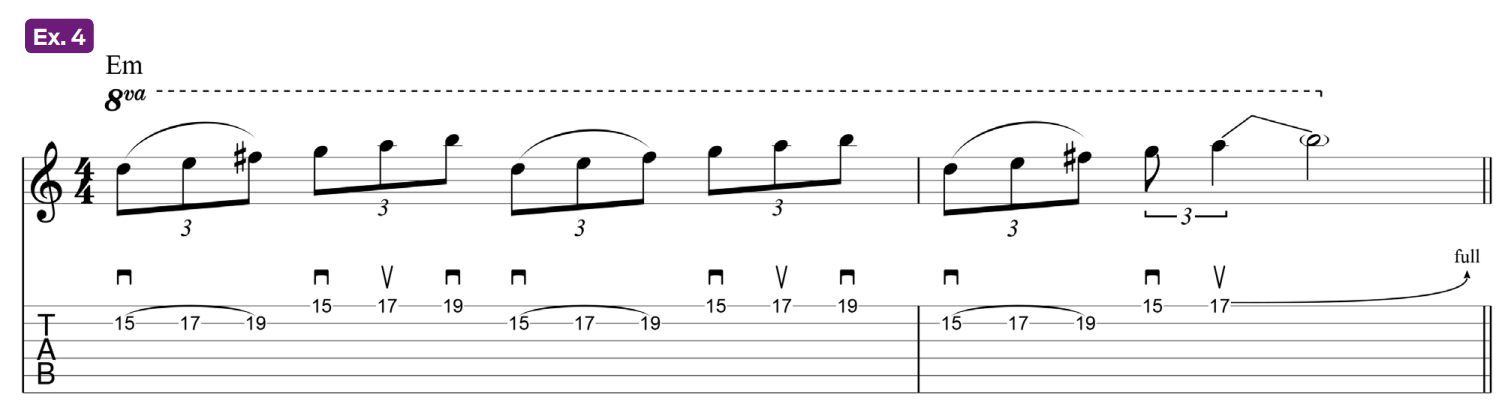

One notable strategy is a workaround Ed used to play three-notes-per-string runs at blistering speeds without the use of consistent alternate picking. It’s something I call an “alternating legato” approach.

Ex. 4 illustrates the concept with a lick reminiscent of one Ed plays in “I’m the One” (Van Halen), where he steps on the rhythmic gas pedal, playing an E minor lick in eighth-note triplets at 236 beats per minute.

He starts on the B string with a lone downstroke initiating a double hammer-on. The time between the three-note legato sequence and the initial downstroke starting the alternate picking on the adjacent high E string eases the challenge of a run like this if it were played with straight alternate picking.

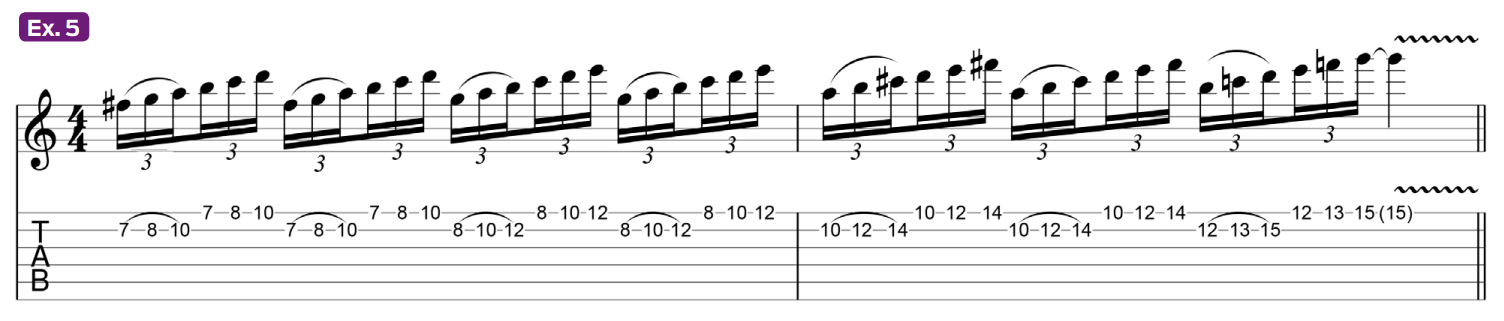

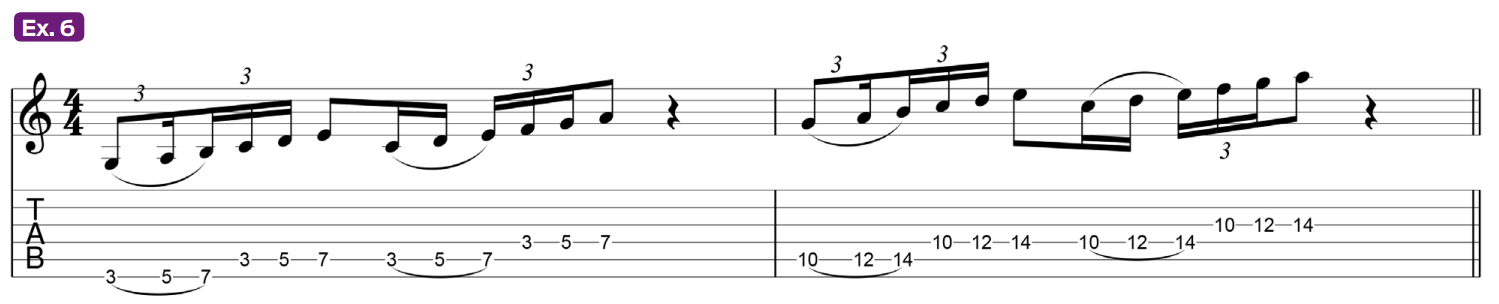

Examples 5 and 6 offer additional demonstrations of this concept while reminding you of breathtaking moments from the nylon-string solo piece “Spanish Fly” (Van Halen II) and the raucous “Girl Gone Bad” (1984), respectively.

Ed’s liberal use of symmetrical fretboard patterns and fingerings provides another economical method for facilitating blazing runs. These are fingerings built on a repeating pattern of steps.

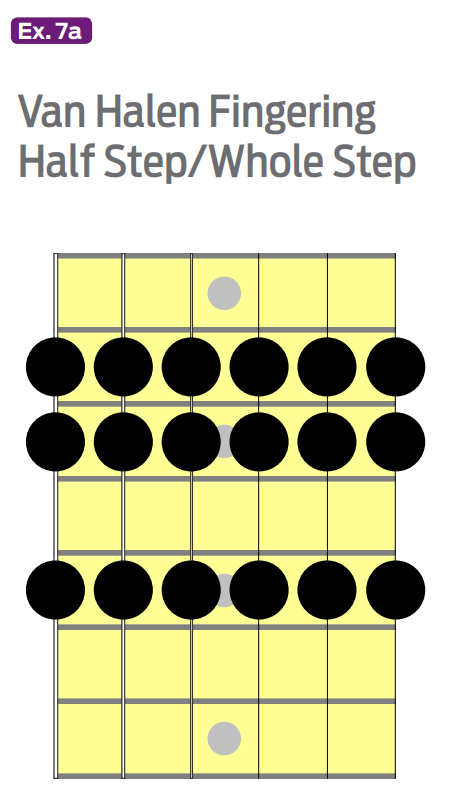

The maestro used his go-to vertical half-step/whole-step fingering shape (illustrated in Ex. 7a) so much that many refer to it as the Van Halen Scale.

Since the note content is not diatonic to any one scale formula, it’s useful to notice not only how he uses the pattern but also how he resolves the inherent melodic-harmonic tension it creates.

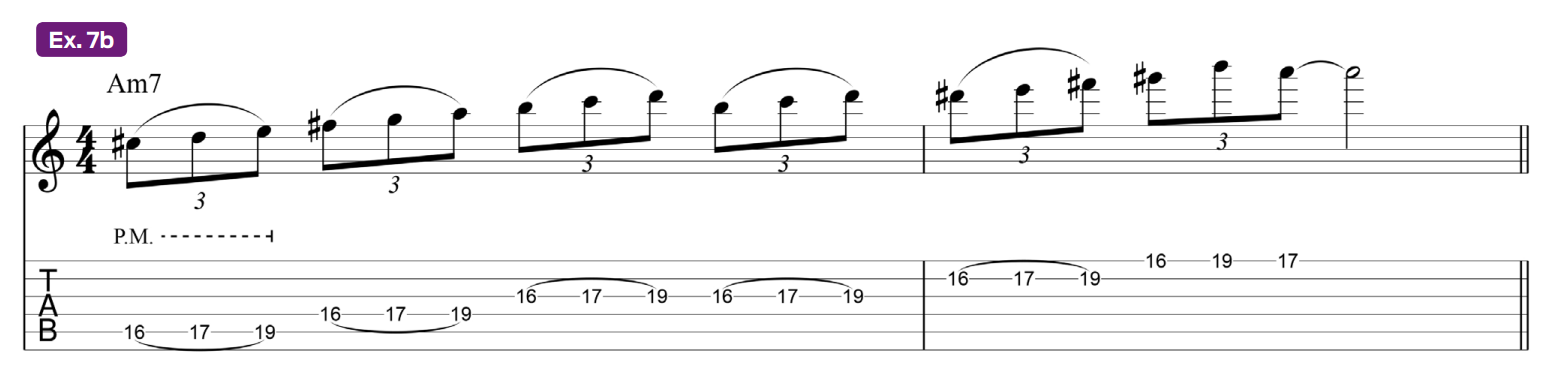

Looking at two brief passages inspired by Ed’s playing in “I’m the One” will provide some insight. Ex. 7b is an ascending run close to what he plays over an Am backdrop that starts on the A string.

With the exception of the first note, C#, the remainder of the run is based on an A minor tonality, with various shadings of Dorian, melodic minor, and the blues scale. The effectiveness lies in the uptempo double hammer-ons, performed in a triplet rhythm, and the concise resolution to the high A root note.

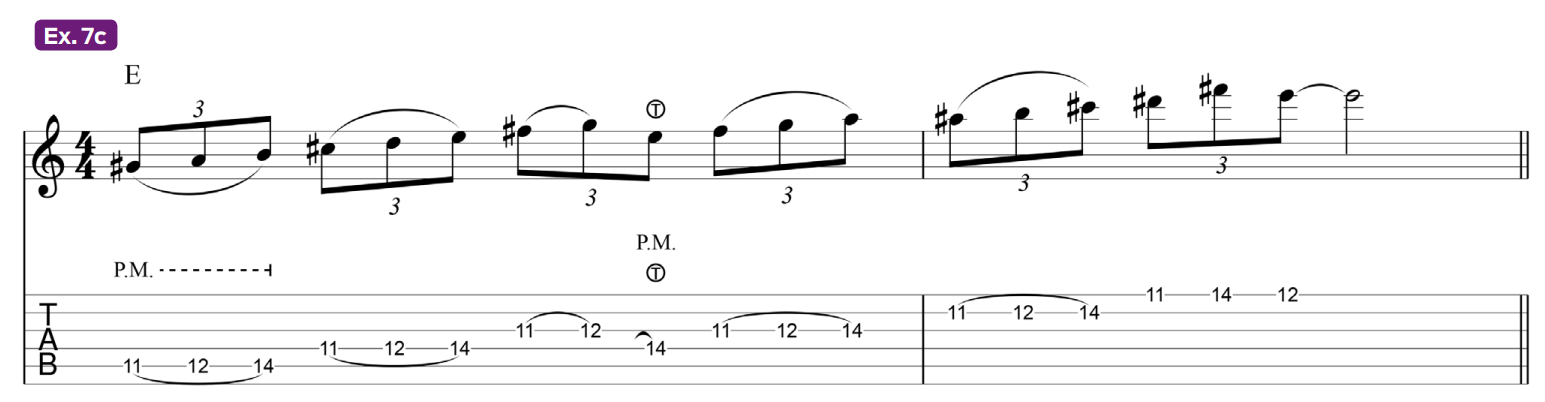

Considering the overall note content in degrees (1-2-b3-3-4-#4-5-6-b7-7), the Van Halen Scale could be played over major triads and dominant seventh chords. In fact, later in the tune, Eddie does something similar to Ex. 7c over an E tonality.

Notice the disjunct movement on beat three of the first bar, where, instead of completing the half-whole pattern, he shows off a core phrasing snippet by playing the root on the lower adjacent string with a palm-muted “ghost hammer.”

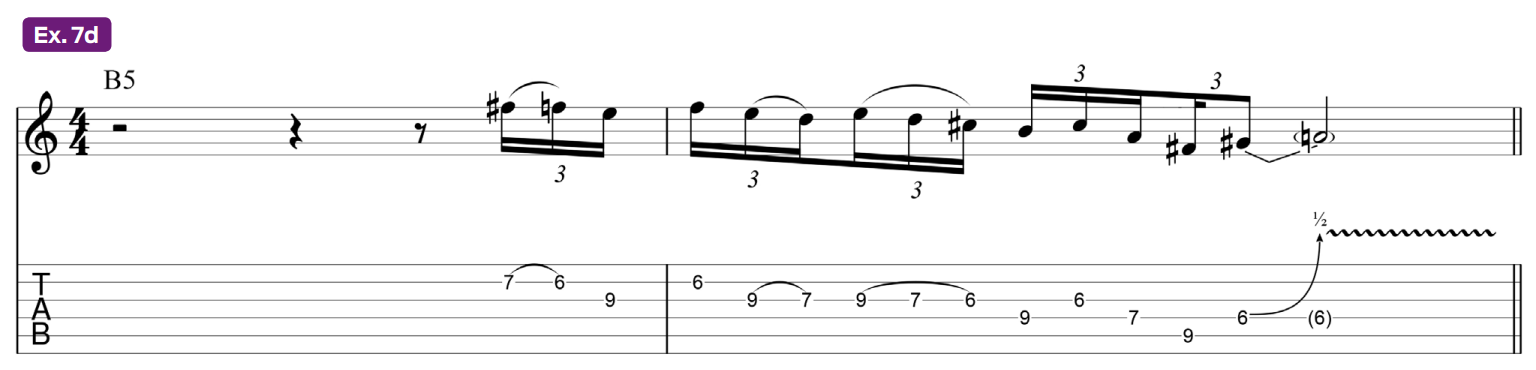

Ex. 7d presents a more broken-up iteration of the Van Halen Scale, this time with a descending run that brings to mind a lick from the solo in “Somebody Get Me a Doctor” (Van Halen II).

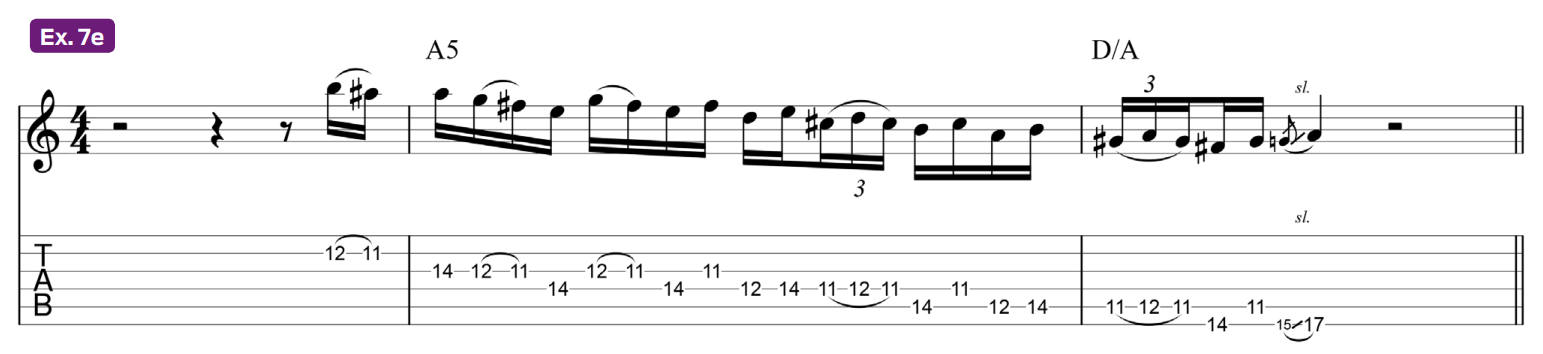

Notice how Ed breaks from the pattern while compressing the string range and morphing the sound to feel like a minor-blues lick. If you’re thinking he just went for licks with a three feel over a static chord, check out Ex. 7e.

This example is inspired by his solo work in “Feel Your Love Tonight” (Van Halen), where, in 11th position, a straight 16th-note phrase smoothly soars over an A5-D/A chord change.

Speaking of signature EVH phrasing, dig the pair of repeating melodic statements: The architecture of the first three notes is played twice on the lower adjacent string pair – and the following seven notes – which include key 16th-note triplet legato flourishes, repeat over descending adjacent string pairs. Classic Van Halen.

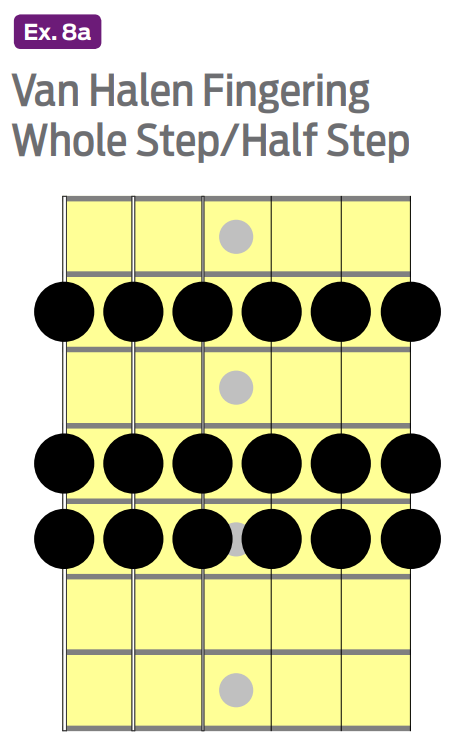

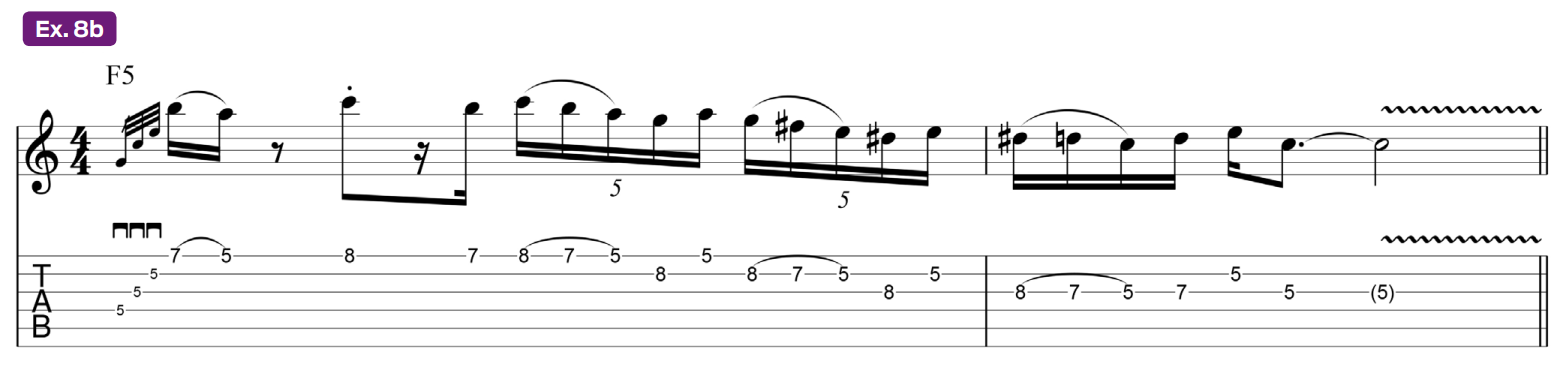

Ed’s use of symmetrical fingering patterns extends beyond his signature half-step/whole-step pattern, and we can reference two examples in “Girl Gone Bad.” Ex. 8a displays an inverse of the Van Halen scale, with a whole-step/half-step vertical pattern.

Ex. 8b reveals a reworking of a lick Eddie plays in the song’s solo over an F5 chord, where he descends that pattern after a rake reminiscent of one he performs in “Spanish Fly.” Take note: Dimebag Darrell, a devout Van Halen disciple, made ample use of this pattern.

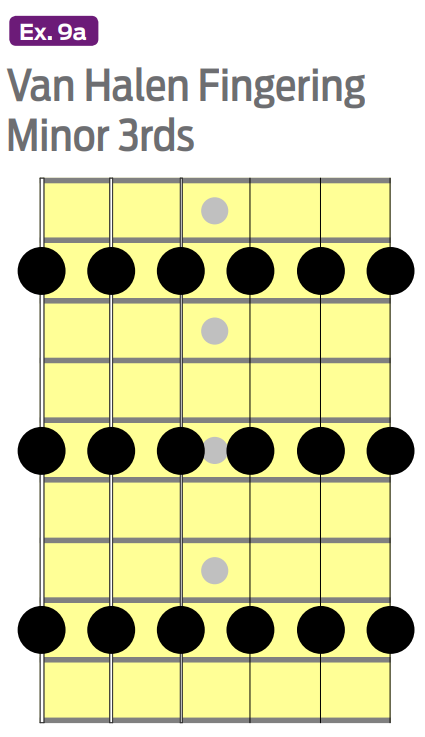

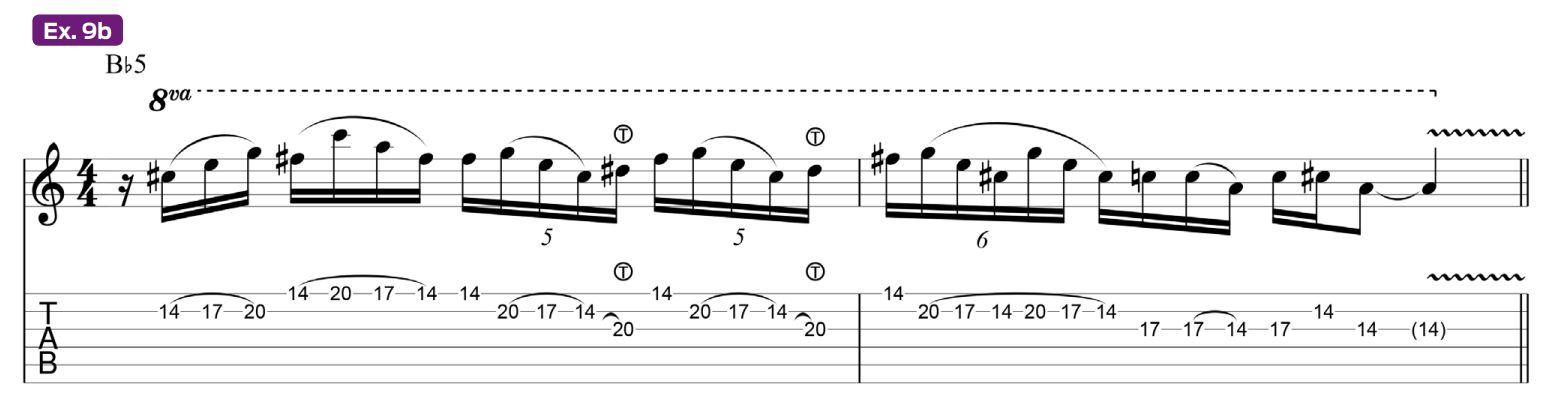

In Ex. 9a, you’ll notice a wider pattern made up of two minor-third intervals spanning six frets! An example of this pattern’s musical application can be seen in Ex. 9b, which is close to what Eddie plays over a Bb5 chord in the solo leading up to the song’s breakdown. The series of single-string diminished-triad arpeggios shows his exploration into playing with fusion-esque tension.

Look no further than the guitarist’s newfound friend at the time, the legendary Allan Holdsworth, for the inspiration behind this visionary approach. Ed’s rhythmic “pocket” is magic, and a bevy of voodoo lies in his penchant for odd-numbered rhythmic phrasing.

Put simply, he naturally felt prime-number subdivisions of the beat – namely 3 (triplets), 5 (quintuplets), and 7 (septuplets). As a result, his licks had a unique push-pull rhythmic swagger.

Look again at Ex. 9b, and in the first bar you’ll discover a pair of quintuplets on beats three and four. This grouping, along with septuplets, freely flowed from Ed’s fingers.

The repeating five-note motives (F# G E C# D#) Ed plays as quintuplets are tried-and-true descending phrases consisting of a picked note on the high-E string, a wide interval three-note pull-off sequence on the B string, and a ghost hammer on the G string at the same fret where the legato pattern started on the higher adjacent string.

Also take note of how the lick rounds out evenly on beat three of bar 2, with his staple up-a-major-second/down-a-major-third motif. The combination of odd-numbered sequences, repetitive wide-interval phrasing, and string skipping to repeat those phrases is uniquely EVH.

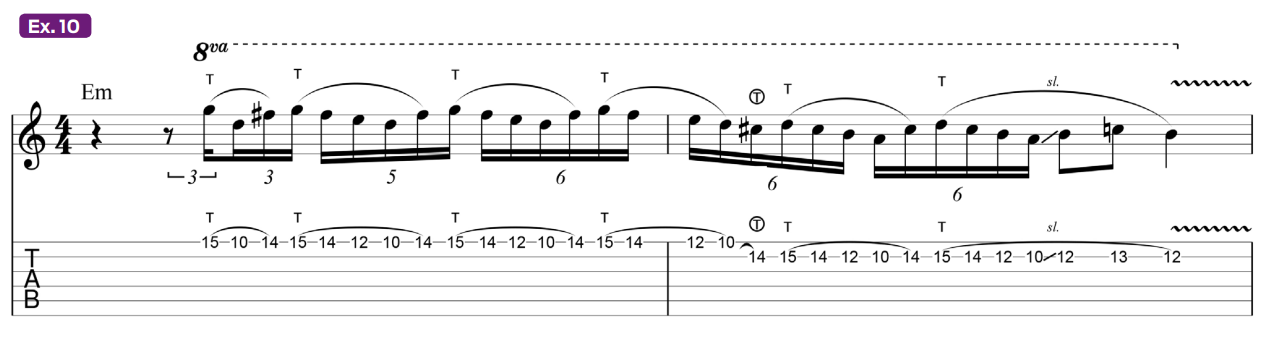

Ex. 10 adds the tapping element within a four-bar variation on a passage from Ed’s celebrated guest solo in Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” (Thriller).

Once again, you can hear a repeating melodic idea placed within groupings of five or six notes but, in this case, unevenly distributed throughout the groupings, resulting in a slick-sounding, infectious lick.

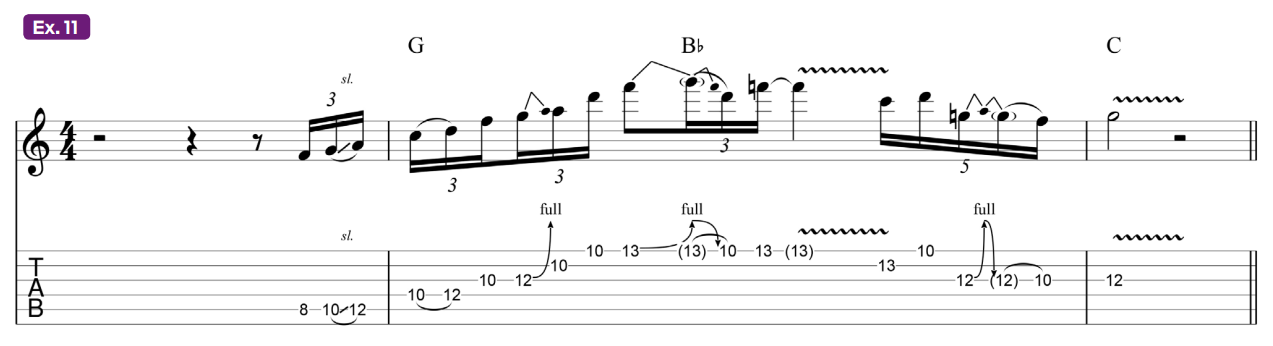

Ex. 11 displays Ed’s odd-numbered-sequence leanings in a blues-lick setting with a reworking of a lick from his solo in “Right Now” (For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge).

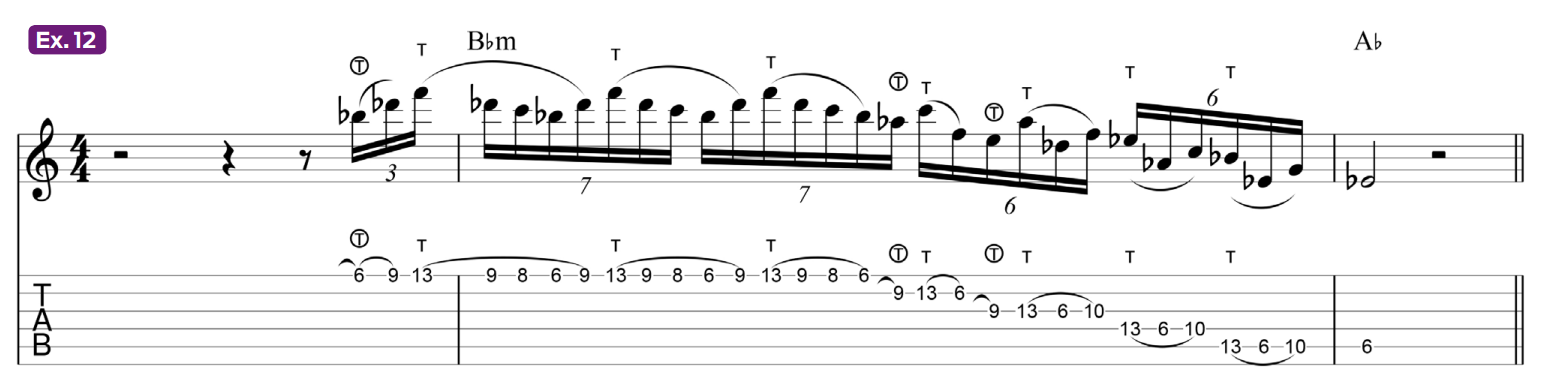

Finally, Ex. 12 introduces groupings of seven. Taking a cue from “Jump,” these septuplets bring to life the longtime notion that Eddie’s phrasing sounded like someone is falling down a flight of stairs, but with style, and, of course, landing on their feet! In the thick of it all, Ed always managed to play great, gutsy, bluesy licks, albeit with an inimitable twist that only he could squeeze.

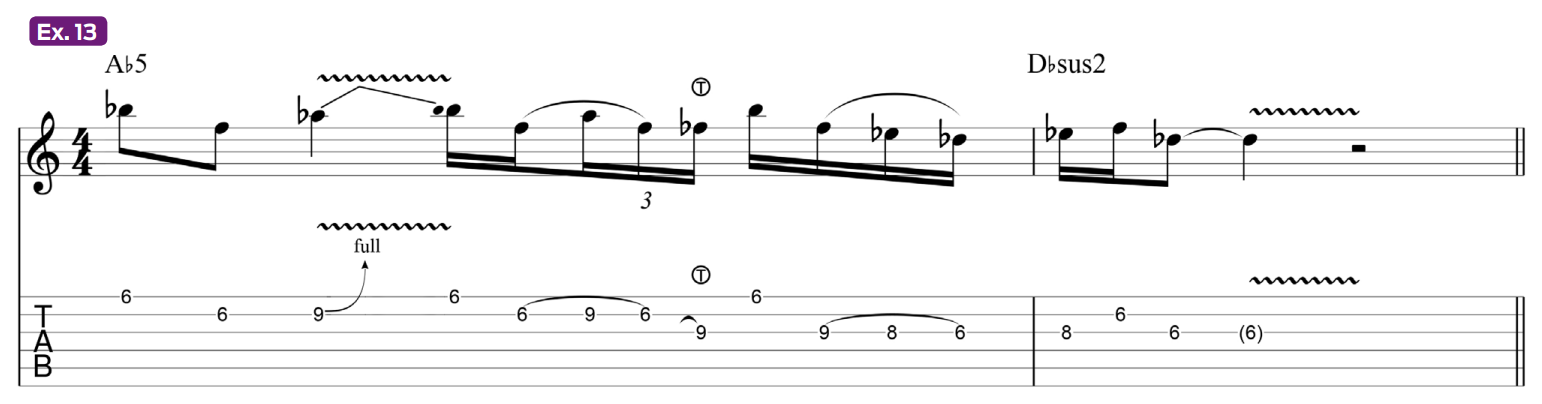

Set in the indispensable root-position minor pentatonic scale with the added b5 – also known as the minor-blues scale – Ed gave us countless moments of b5 fire with licks similar to Ex. 13.

Once again in the spirit of the solo from “Jump,” the standout elements are the aforementioned five-note motif (this time with a hammer-on/pull-off); the skip from the ghost-hammered b5 (Fb) on the G string’s ninth fret back up to the sixth fret, high-E string (Bb), only to jump back down to the b5; and a double pull-off into that major-second/down-a-major-third snippet.

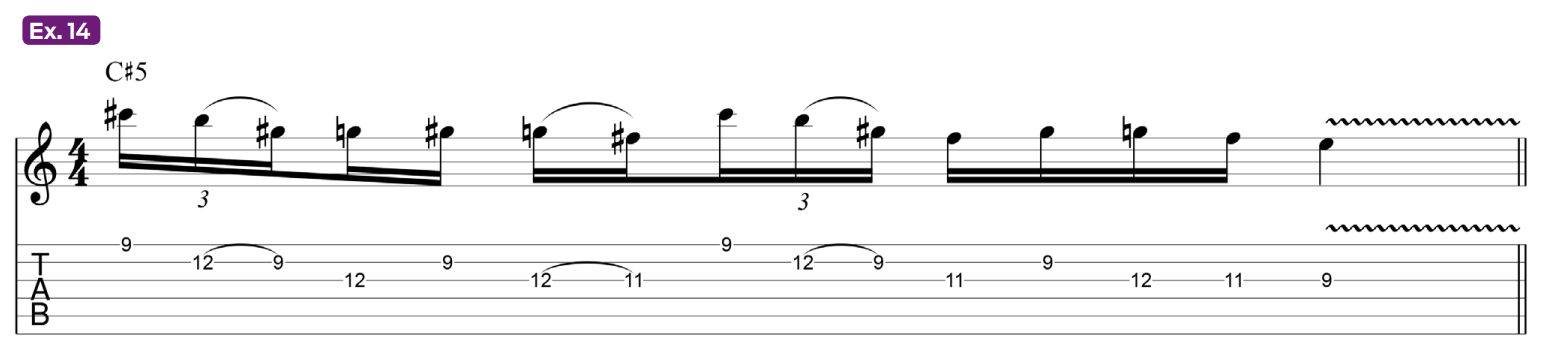

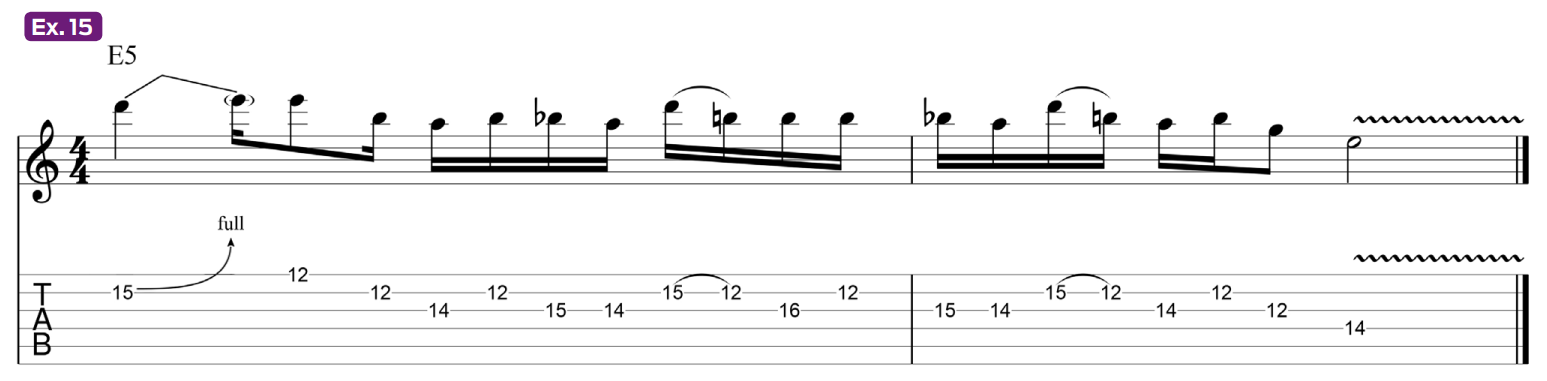

Examples 14 and 15 are close to what Eddie plays in “Feel Your Love Tonight.” You can see more back-and-forth with the b5 (G) in Ex. 14, where Ex. 15 tightens things up with the inclusion of the 5 (B) against the b5 (Bb), making for a tricky-sounding zigzag chromatic cadenza.

When it comes decoding the deeper components of what made Eddie Van Halen such an extraordinary guitarist, there are many secrets in the sauce. I have merely offered you a brief glimpse into the pot. Yet, perhaps the most important, “special” if you will, ingredient was always right there on his face – that ear-to-ear grin.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Chris Buono is a top-selling TrueFire Artist with nearly 50 instructional videos, and a featured instructor on guitarinstructor.com. Bookending his years as a Berklee professor, he authored eight books, including the popular Guitarist’s Guide to Music Reading and his most recent publication, How to Play Outside Guitar Licks.

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band