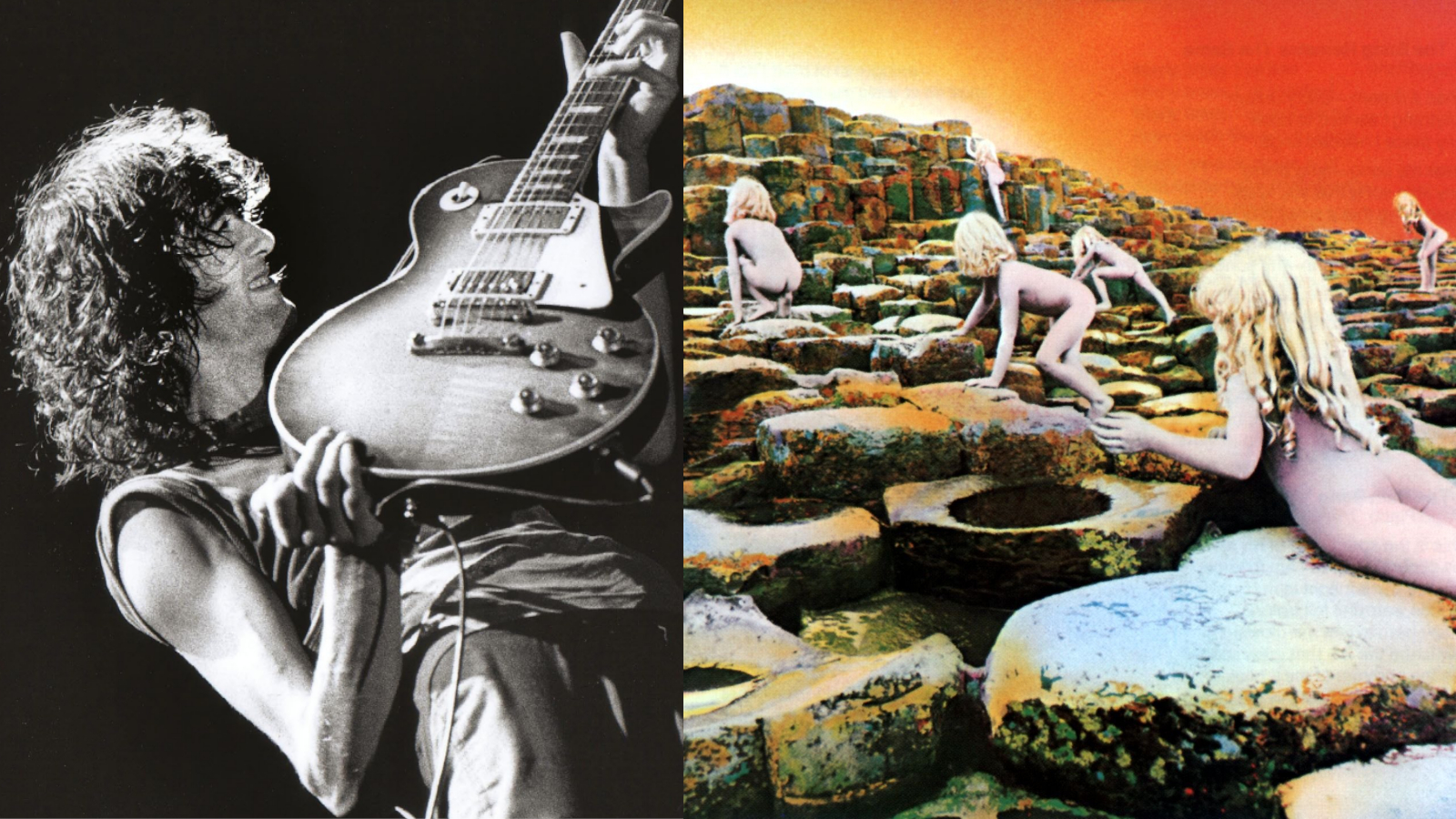

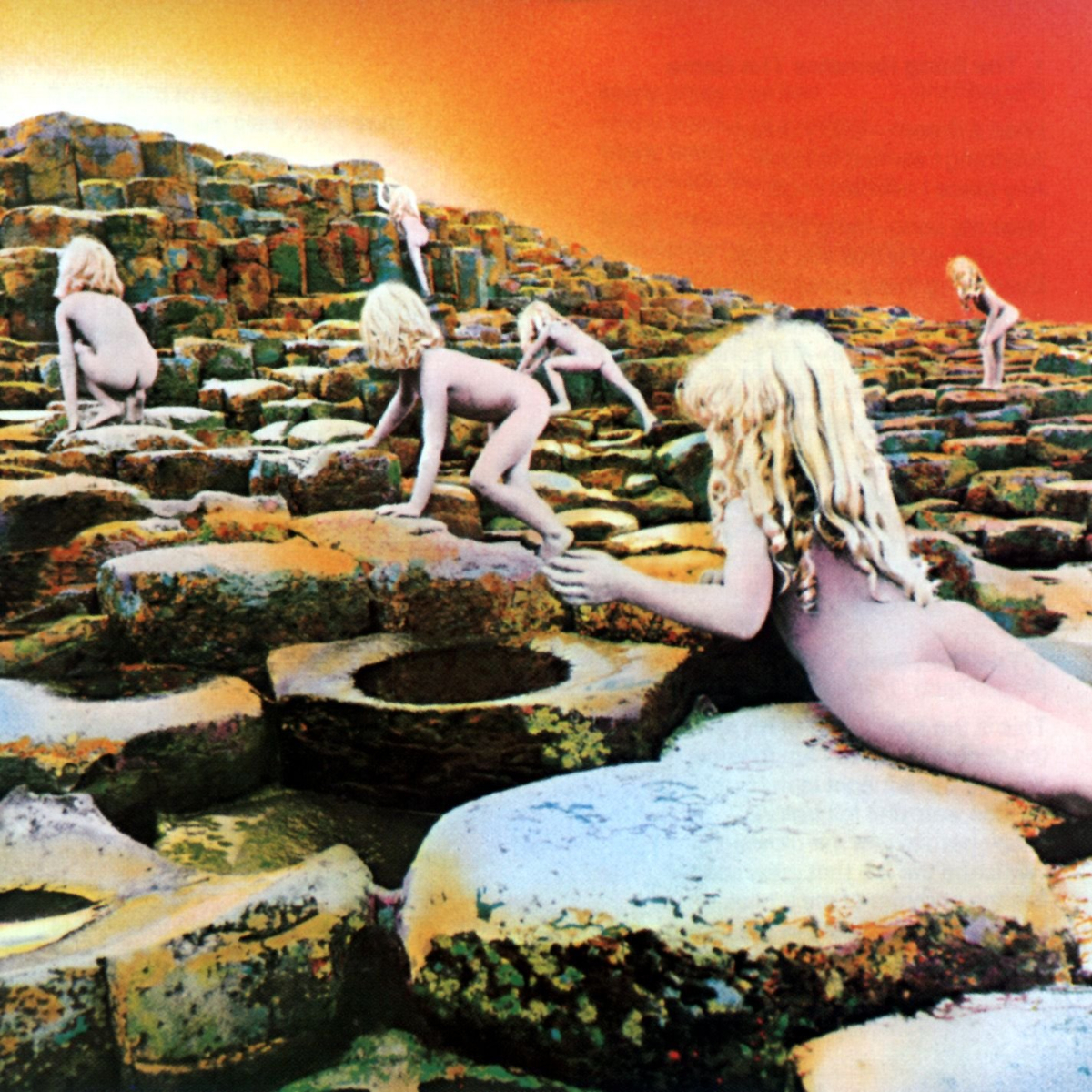

Discover How Jimmy Page’s Genre-Melding Musical Innovations on ‘Houses of the Holy’ Helped Led Zeppelin Reach a New Creative Peak

As this classic album turns 50, we explore how the guitarist blew the lid off his band’s blues-based formula

1973 was quite an eventful year. Then-Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned over charges of tax evasion as the Watergate scandal raged, the Miami Dolphins finished with a yet-to-be-repeated perfect NFL season, and director Martin Scorsese premiered his seminal film, Mean Streets.

Yet, even with these and many other newsworthy events swirling through the U.S. that year, the music world had its share of noteworthy releases. They include such albums as Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, Queen’s self-titled debut, Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions, and the album we’re celebrating in this lesson, Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy.

Arriving on the heels of that group’s massively successful 1971 release, Led Zeppelin IV (the album that featured “Stairway to Heaven”), Houses of the Holy was something of a departure, as the band’s previous albums were darker and more bluesy.

In fact, it’s the only record in the Zeppelin catalog that does not include a blues-based song.

So let’s mark this 50th anniversary with a Houses tour of sorts, wending our way through the album’s tracks in order, as we stop to take in some of the unique attractions along the way.

Houses of the Holy blasts out of the starting gate with the restless pulse of “The Song Remains the Same.” Guitarist Jimmy Page masterfully layers jangly electric 12-string guitar parts, all played on his Fender Electric XII.

It’s the only record in the Zeppelin catalog that does not include a blues-based song

With the absence of Zeppelin’s trademark distorted guitars and massive single-note riffs, this opening track signals that the band has something different in store this time out.

With a bright and relatively clean tone, Page’s guitars combine an open-D-string drone with staccato triad stabs.

The guitarist is often heralded for his savvy orchestration of guitar parts, and here, he characteristically demonstrates his creativity: The two guitars contributing the chordal jabs are not simply doubled, as would often be the case in a situation like this.

Let’s take a closer look.

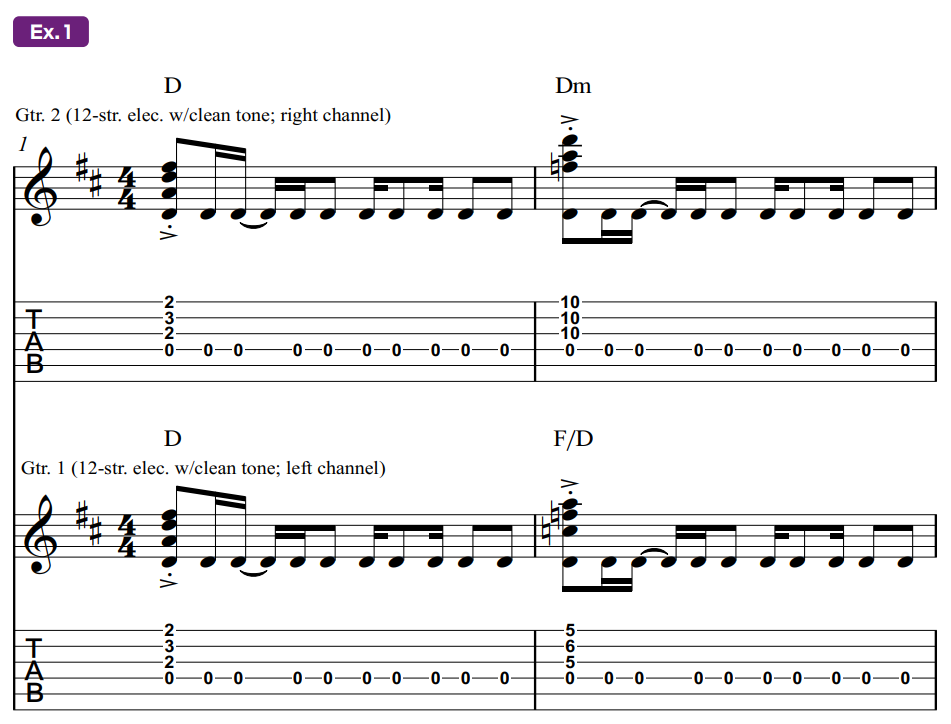

In Ex. 1, inspired by the song’s intro, the two guitars start with the same open D chord.

But as Gtr. 1 moves up the fretboard with a series of climbing triad voicings on the top three strings, Gtr. 2 follows suit, but while playing different triads that, when heard against Gtr. 1’s, add “color tones” to the aggregate harmony that convey more complex and richer-sounding chordal qualities, namely Dm7 (bar 2), G6/D (bar 3) and A9/D (bar 4).

By orchestrating parts in this way, Page subtly creates a wider and more colorful tonal spectrum. Pretty cool. And there’s more magic to come.

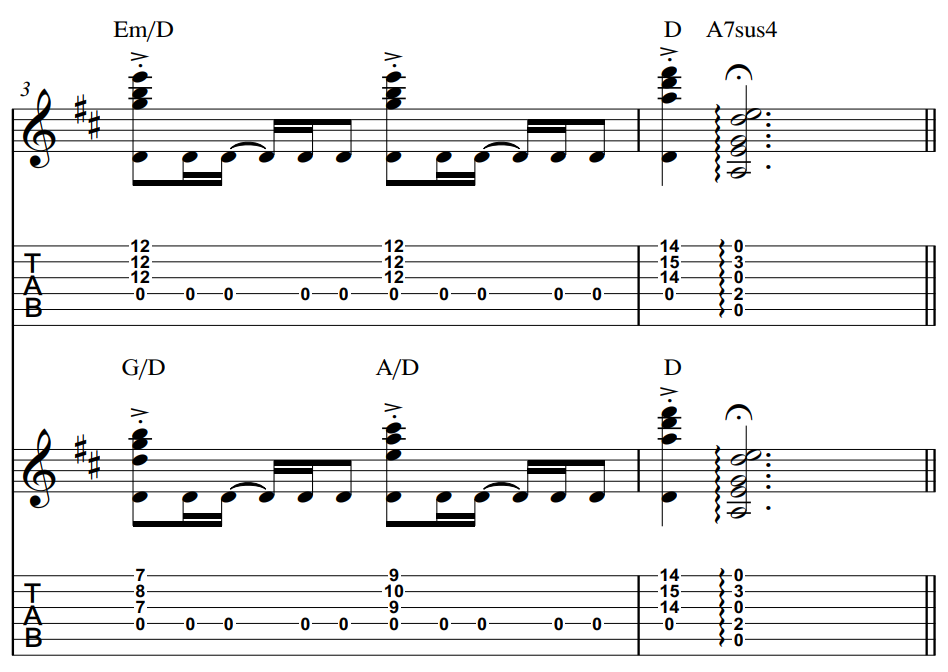

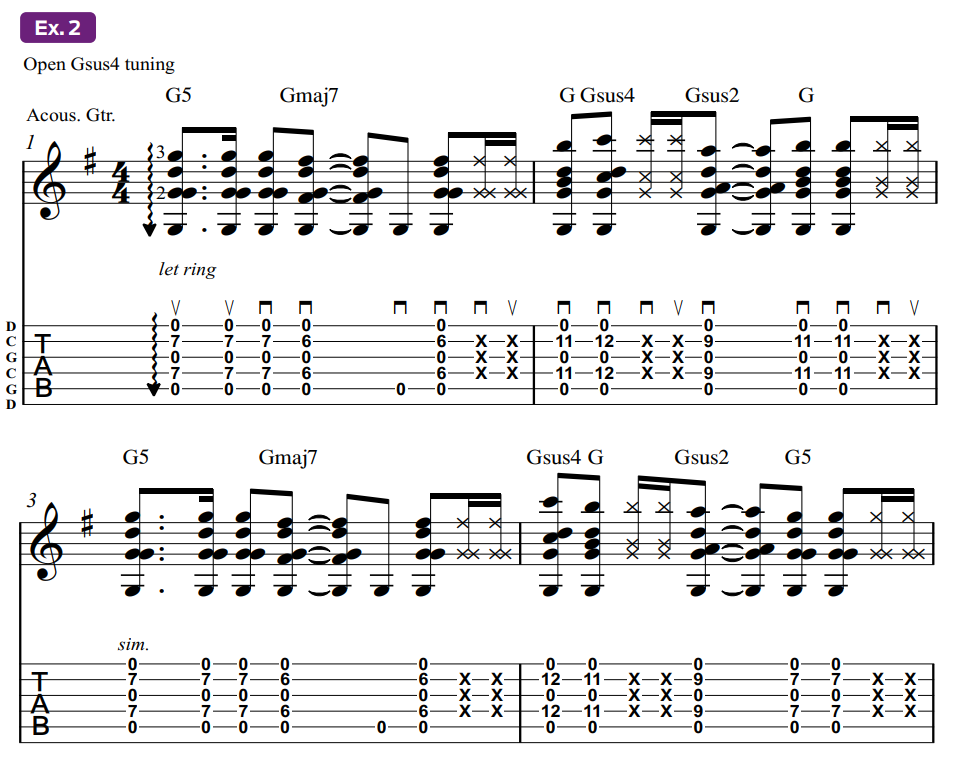

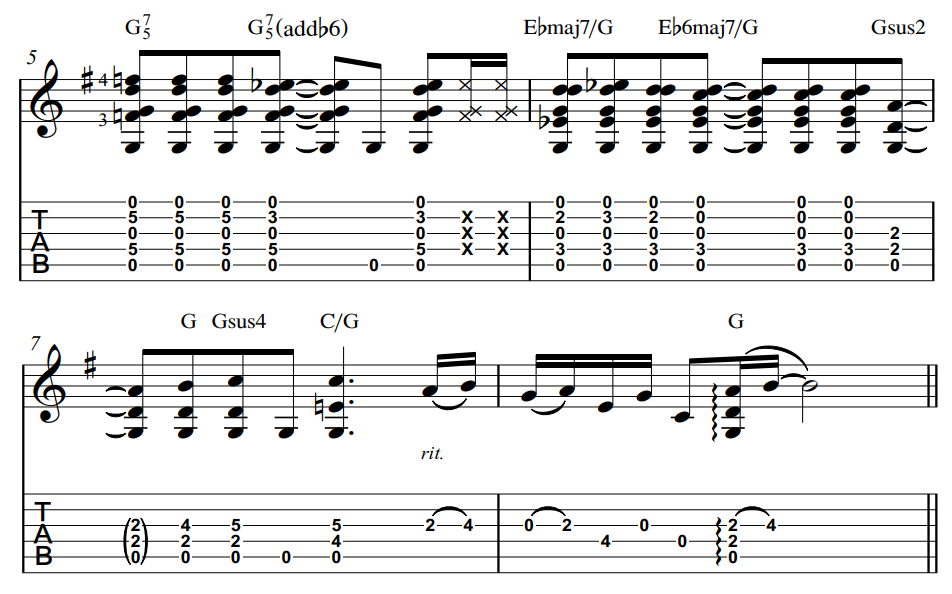

Next is the beautiful acoustic ballad, “The Rain Song,” for which Page ingeniously employed what could be called open Gsus4 tuning (low to high: D, G, C, G, C, D).

With it, he explores and exploits simple chord shapes – just two fretted notes surrounded by ringing open strings.

Ex. 2 is inspired by Page’s acoustic playing throughout this track. Houses of the Holy would seem to be an album of dissonances, both melodically and rhythmically, and there are all sorts of examples scattered throughout.

Take the acoustic intro to “Over the Hills and Far Away.” Page’s strumming pattern accents beat 1’s eighth-note upbeat in a way that makes it feel as if it’s the downbeat (beat 1) and makes us think that perhaps the song isn’t in 4/4 time, even though it is.

It’s challenging for us to find the rhythmic home base – beat 1 – and for a moment, we lose our musical equilibrium, in a playful way.

But let’s discover an even more intricate example of “rhythmic dissonance” that comes a bit later in the song. Just after the guitar solo, at 3:01, there’s a short, musically enigmatic interlude, which has Page’s, bassist John Paul Jones’ and drummer John Bonham’s parts combining into what may be described as a polyrhythm, a simultaneous combination of contrasting rhythms.

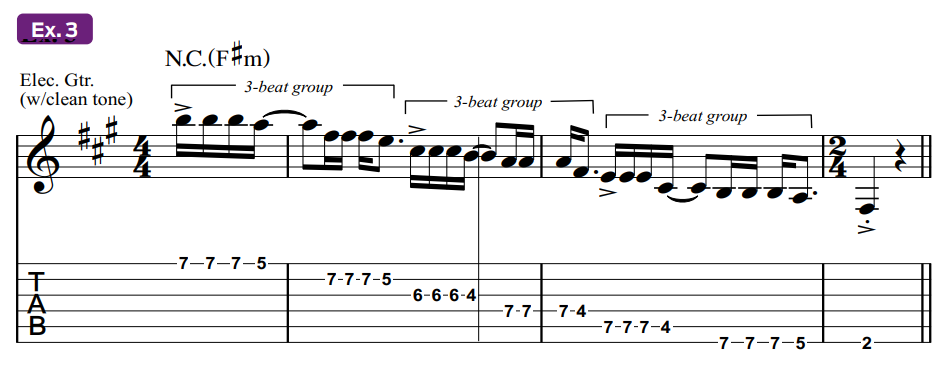

Here, Page’s riff starts as a pick-up on beat 4, then continues for two bars in successive groups of three beats.

This creates the aural illusion of the guitarist playing in 3/4 while drummer John Bonham (seeming not to notice) grooves along in 4/4 with a straightforward rock beat – kick drum on beats 1 and 3, and snare drum on 2 and 4.

Ex. 3 offers a phrase constructed using a similar approach. Notice in “Over the Hills,” how the “three-against-four” polyrhythm ends with the band reconnecting at beat 1 of a bar of 2/4, which enables them to smoothly segue back to the song’s main instrumental hook riff together.

More rhythmic adventures appear at our next stop, the funky, obviously James Brown-inspired “The Crunge.”

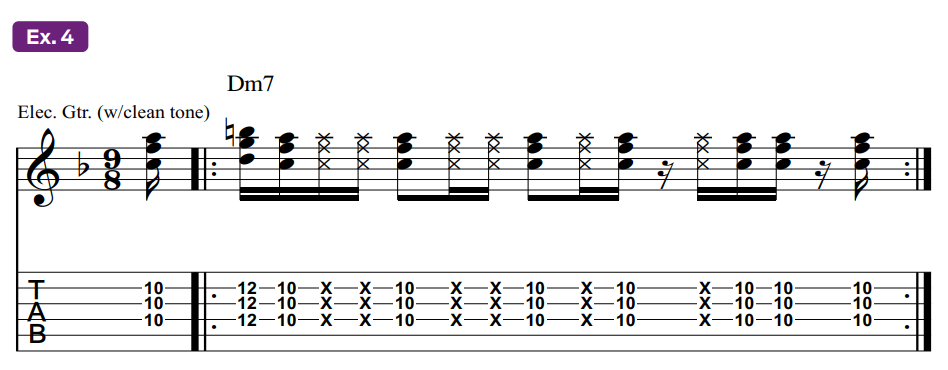

Kicking off in 9/8 meter, the song features Page’s clean electric guitar “scratch” strumming a dominant 9th chord, with lots of fret-hand-muted 16th-note rhythms, as it syncs with Bonham’s tricky drumbeat and Jones’ nimble bass line.

The 9/8 meter here may best be reckoned as 8/8, which is the fractional equivalent of 4/4, with an extra eighth note tacked onto the end of each bar.

Using a foundational Dm7 chord grip, Ex. 4 offers a funky rhythm guitar part that’s rhythmically along the lines of what Page played.

A visit to this playful track wouldn’t be complete without stopping to notice vocalist Robert Plant’s humorous allusion to the Godfather of Soul, as he searches for “the bridge,” capping off the song with a tongue-in-cheek “Where’s that confounded bridge?!”

Onward to Houses’ next cut, “Dancing Days,” where we come upon an instance of melodic dissonance right from the get-go.

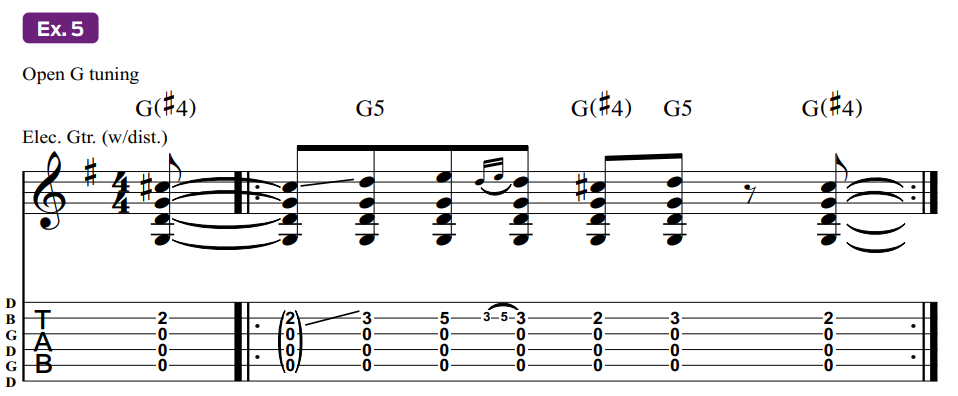

Page tuned his Gibson Les Paul to open G tuning here (low to high: D, G, D, G, B, D) and enters with a sinister guitar line featuring the raised 4th (#4) of the key.

We’re in G major, where the 4th degree would normally be C, but here the creatively clever guitarist gives a nod to the G Lydian mode (G, A, B, C# , D, E, F#), which is nearly identical to the G major scale, or G Ionian mode (G, A, B, C, D, E, F#), except that the 4th scale degree is raised a half-step, to C#.

This creates an interval of an augmented 4th (three whole steps) between the root, G, and the raised 4th, C#.

Sometimes referred to as the “devil’s interval,” its occurrence gives the distinct impression that something malevolent is afoot.

Ex. 5 presents a similarly styled riff that brings to mind the song’s intro.

Offering an interesting change of musical scenery, our next stop is “D’yer Mak’er,” a quasi-reggae song, the title of which pokes fun at the British pronunciation of “Jamaica.”

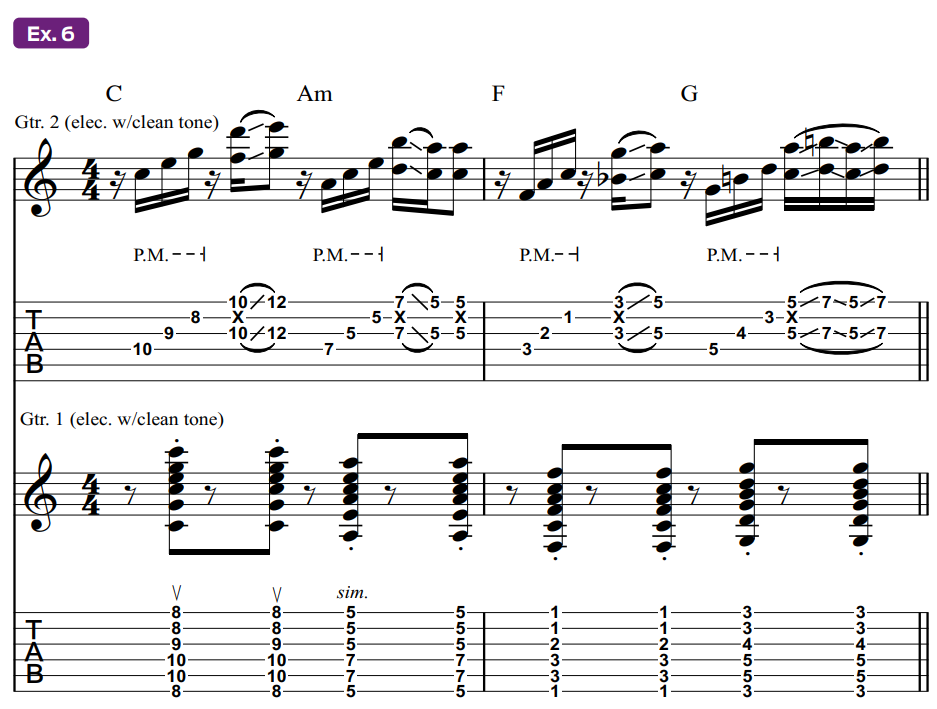

Once again, Page shows his mastery of layering complementary guitar parts, as he first adds a traditional reggae-style rhythm part consisting of off-beat chordal stabs, strummed with upstrokes.

He then works his magic by adding a second rhythm part, which evokes island rhythms by combining palm-muted single notes with Steve Cropper-like, R&B-style phrases, not unlike Ex. 6.

We next arrive at “No Quarter,” a dreamy song where JPJ’s keyboards take the lead, until Page’s dirge-like guitar riff enters on the song’s chorus.

The guitarist’s riff harkens back to the overdriven six-string sounds of previous Zeppelin classics, and the instrument being tuned down one half step (low to high: Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Bb, Eb) adds even more “grunge” to the proceedings.

Speaking of which, in the 1990s grunge era, the opening riff to Soundgarden’s “Spoonman” seemingly hinted at Page’s prescient power chord-driven riff.

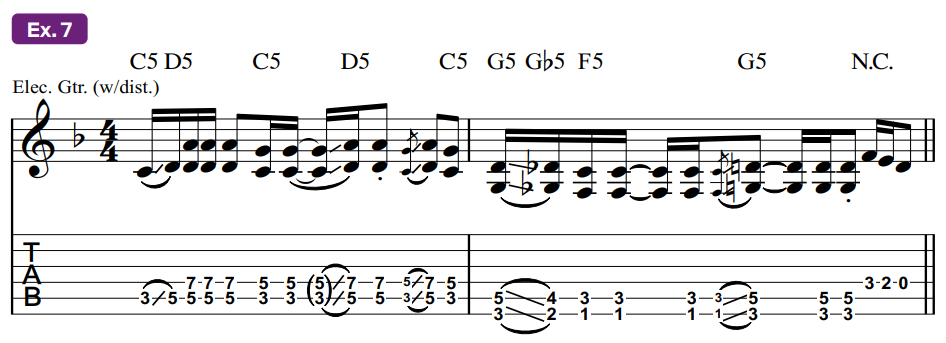

Ex. 7 brings it to mind as well, although it’s played in standard tuning.

Returning to the dreamier section of “No Quarter,” which serves as the backdrop for Page’s guitar solo, we find the guitarist venturing beyond the trusty familiarity of the pentatonic and blues scales with some colorful “cool jazz” licks that evoke the modal style spearheaded by trumpeter Miles Davis in the late 1950s.

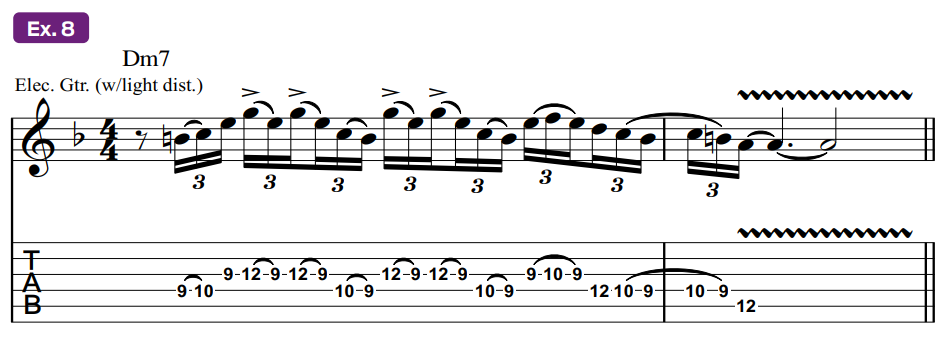

Ex. 8 brings to mind some of the tasty licks Page crafted in his solo.

Playing over a Dm7 chord, his phrases come out of the D Dorian minor mode (D, E, F, G, A, B, C), which distinguishes itself from D natural minor (D, E, F, G, A, Bb, C) by its raised-6th scale degree, B.

Notice how this phrase emphasizes a C major triad (C, E, G), to stress the harmonic extensions, or color tones, of the Dm7 chord. (C, E and G are its b7th, 9th and 11th, respectively.)

The rhythm is exclusively triplet-based, creating a restless quality that contrasts nicely with the mellow rhythm-section accompaniment.

Our last stop is “The Ocean” – old-school Zeppelin… at least at the outset.

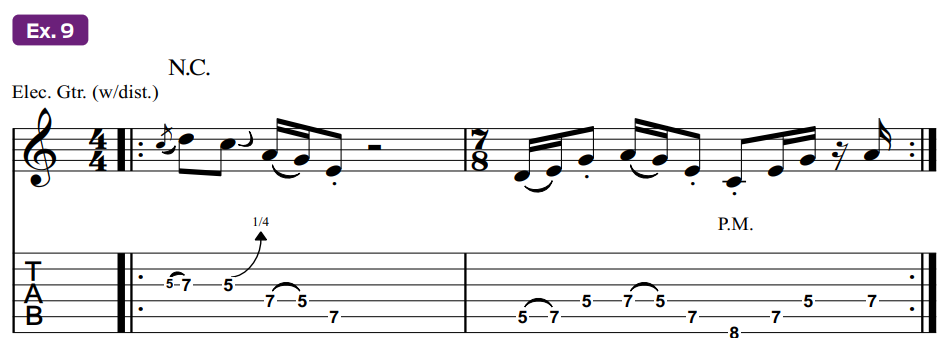

Up until now, we’ve experienced some rhythmic experimentation involving polyrhythms and songs in off meters. For the opening riff here, Page finds yet another avenue to explore – shifting meters – as he alternates between 4/4 and 7/8.

As with “The Crunge,” we can think of 7/8 as 8/8 – again, the same as 4/4 – but this time with one less eighth note.

It’s smooth sailing right up until the end of the two-bar phrase, where we take a sharp U-turn and head right back to the beginning.

Inspired by this riff, Ex. 9 shifts meters to achieve a similarly jarring effect.

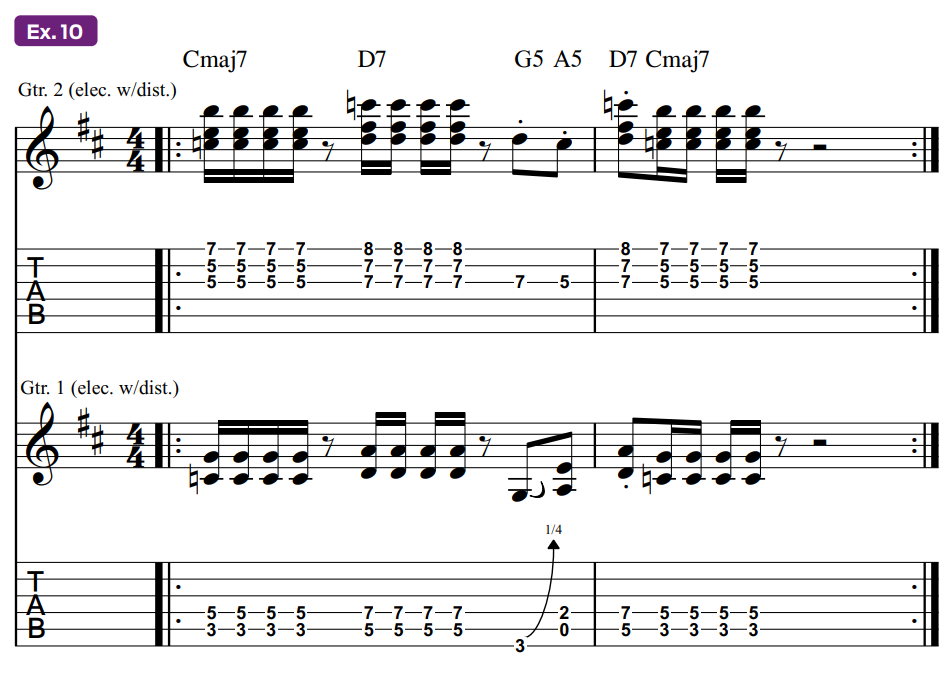

Lastly, “The Ocean” features some of the same kind of arranging/orchestration techniques Page previously used in “The Song Remains the Same.”

The guitarist again stacks chords on top of each other, and here he creates the illusion of a guitar orchestra.

In the verses, Page plays a shifting-power-chords riff. But when the riff returns after the solo, he adds a higher-voiced guitar on top.

The combined parts result in some unexpected jazzy dominant 7th and major 7th chords, but played with semi-distorted guitar tones, which delivers a nice bite.

Ex. 10 is reminiscent of this section.

On our trip through Houses of the Holy, we experienced Jimmy Page’s creativity, as he pushed the boundaries of what Led Zeppelin had accomplished to date, searching for new sounds and styles.

He summed it up best, when he said in the Holiday 2014 issue of Guitar World, “I was pushing myself to explore new areas of harmony. I wanted to investigate those outside edges – maybe push myself over the edge!

“I’m surprised, really, that I’m here to tell the tale.”

Have a question or comment about this month’s lesson? Feel free to reach out to Jeff Jacobson on Twitter @jjmusicmentor or at jeffjacobson.net. Jeff offers private guitar and songwriting lessons virtually.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band