DADGAD for Dummies (Psst: You Already Know 50 Percent of This Tuning)

With its evocative and enigmatic sound, DADGAD is one of the guitar’s best-kept secrets.

“I use open and alternate tunings to get music out of the guitar,” says fingerstyle master Martin Simpson. “Do you want to move people? You can’t be struggling with holding down the damn strings. Alternate tunings can help you unlock chords and melodies that might be difficult or impossible to play in standard tuning.”

With its evocative and enigmatic sound, DADGAD is one of the guitar’s best-kept secrets. Blues and folk guitarists often delve into open D (low to high, D A D F# A D) and open G (low to high, D G D G B D) tunings, but only the most intrepid pickers investigate DADGAD.

Yet Simpson, one of the world’s preeminent DADGAD players, insists that it’s not a difficult tuning.

“Actually, it’s quite easy to get gorgeous sounds,” he says. “I’ll show you two ways to approach DADGAD, but first, just listen to the open strings.”

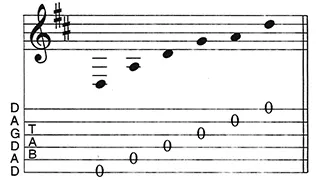

These open strings are shown, from low to high, in FIGURE 1. To move from standard tuning to DADGAD, simply drop the first and with strings down a whole step to D, and then lower the second string, B, a whole step, to A.

FIGURE 1

“DADGAD’s open A, D and G strings are the same as in standard tuning! That means 50 percent of this tuning is completely familiar to you.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

—Martin Simpson

DEMYSTIFYING DADGAD

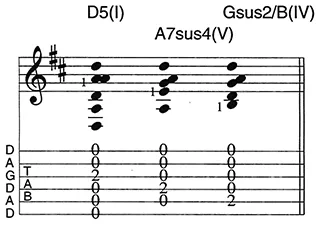

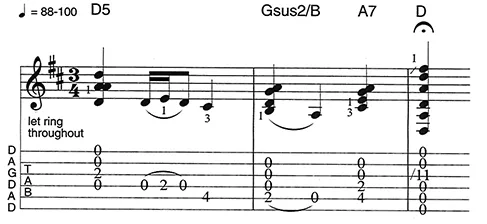

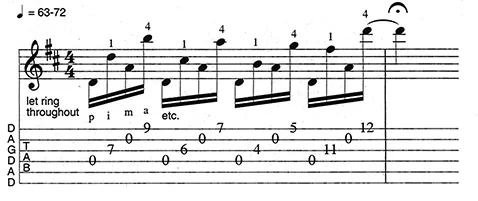

“The first thing you’ll notice,” says Simpson, “is that DADGAD is neither major nor minor—you can go either way. Open-D and open-G tunings push you in a particular harmonic direction, whereas DADGAD is delightfully ambiguous. To play songs, you need I, IV and V chords, right? In DADGAD, you can play rich harmony by merely fretting one note with your index finger [FIGURE 2].

FIGURE 2

“For a I chord, you get D5. There’s no 3, so melodically you can go major or minor. All the strings are open, except the third, which you play at the second fret.

“Now simply move your index finger over to the fourth strings and you’ll get A7sus4—a vibey V chord that uses five strings. Again, there’s no 3, so you have a nebulous sound. Finally move your index finger to the fifth string and strum the same five strings. Here we get Gsus2 with B, the 3, in the bass. This is our IV chord.”

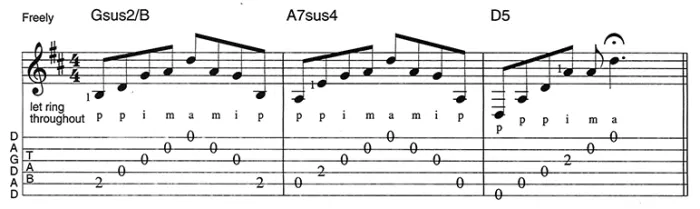

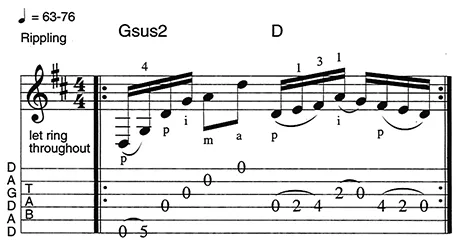

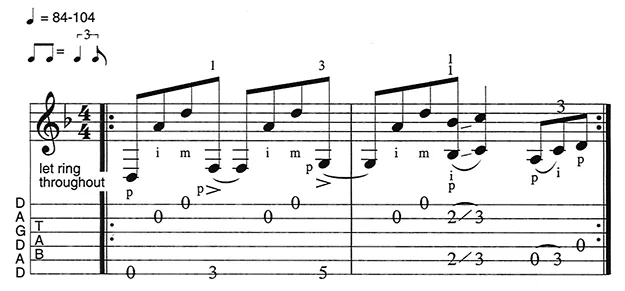

Once you’ve moved back and forth through the chords to hear their sound, play FIGURE 3. With little effort you can adapt this arpeggiated IV-V-I progression to fit dozens of folk and country ballads.

FIGURE 3

Carefully follow the picking-hand fingering. Like a classical guitarist, Simpson uses his thumb (p), index (i), middle (m) and ring (a) fingers for chordal passages. In addition to opening your ears to the lush melodic and harmonic possibilities of DADGAD, this lesson’s exercises will invigorate your fingerstyle chops.

LINGERING FINGERS

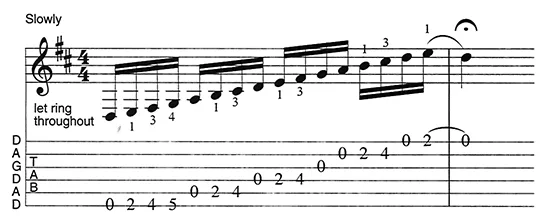

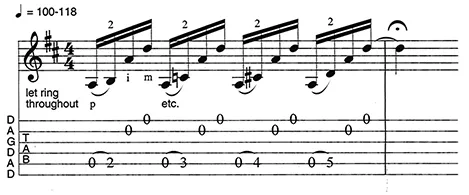

“The next step,” says Simpson, “is to ornament three ringing chords with scale-tone runs. You can fill out D5, Gadd2 and A7sus4 using notes from this D major scale pattern.”

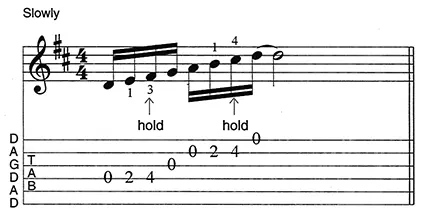

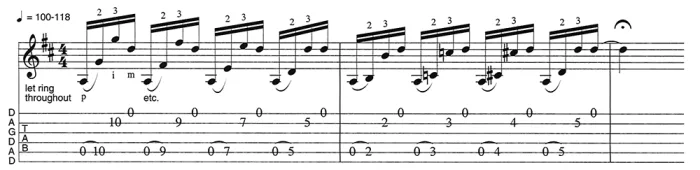

As he plays FIGURE 4A, Simpson is careful to keep all the strings sustaining as long as possible. In the upper octave, played on the top four strings, he leaves his fingers on fretted notes long after they’re attacked. This “park your fingers until needed elsewhere” technique creates a jangly harp-like effect. For instance, if you keep your 3rd and 4th fingers planted on F# and C#, as indicated by the “hold” markings in FIGURE 4B, you’ll wind up with FIGURE 4C’s deliciously dissonant four-string cluster. The two minor seconds (F#-G and C#-D) lend a welcome clang to the otherwise straight-laced D major scale.

FIGURE 4A

FIGURE 4B

FIGURE 4C

This is an essential technique. Simpson often creates piquant harmony within a melodic passage by sustaining a fretted note against an adjacent open string. The resulting intervals—typically major or minor seconds—add ear-tweaking tension to a line. To make this work, you need to arch your fretting fingers so they don’t impede the open strings’ vibrations.

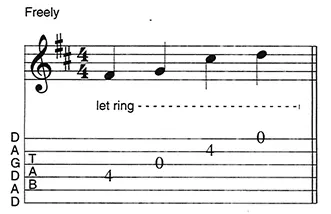

FIGURE 5 illustrates the process. When you hammer onto F# (the and of beat three), hang onto it until you need to pull off to E (the and of beat four). For your efforts, you’ll be rewarded with a cool minor second—open G against F#—in the middle of your run. Repeat the Gsus2-D passage until the notes ripple smoothly through your instrument.

FIGURE 5

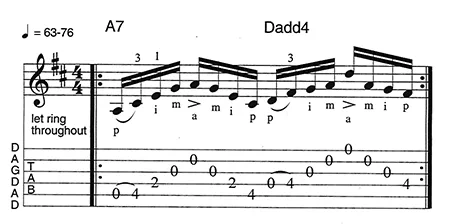

In a similar vein, FIGURE 6 moves from A7 to Dadd4. This time, the minor second occurs at the end of the phrase. “You’re accomplishing two things with this progression,” says Simpson. “You’re learning where the scale tones lie in DADGAD, and you’re introducing the 3 into the chorus—C# for A7sus4 and F# for D5.

FIGURE 6

“It doesn’t take much to embellish the three chords we’ve learned,” he adds, playing FIGURE 7. “A simple bass line can create momentum and keep the harmony interesting.” In bar 1, be sure to sustain D5’s top three strings against beat two’s ornament and beat three’s C#.

FIGURE 7

“You can learn so much about arranging for guitar by experimenting with different registers,” says Simpson. “Listen to these voicings [FIGURE 8]. Can you hear what happens when I pay C# in the bass as opposed to the melody? The difference is enormous.”

FIGURE 8

Here’s a tip: Whenever you discover a new DADGAD voicing, try shifting any note up or down an octave. Some fingerings will “click,” and you’ll quickly multiply your harmonic options. “By changing registers,” Simpson adds, “You’ll begin to realize what bass and melody each contribute to an arrangement.”

OLD WINE, NEW BOTTLES

“We’ve been looking at DADGAD through the lens of our I, IV and V chords,” says Simpson. “But there’s another way to understand it. Up to this point, our examples have involved a new way of thinking, yet DADGAD’s open A, D and G strings are the same as in standard tuning! That means 50 percent of this tuning is completely familiar. If you’ve learned triads in standard tuning, you can apply this knowledge to DADGAD.”

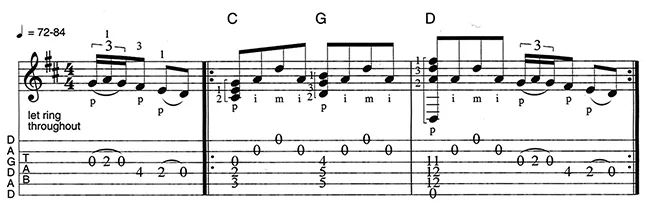

In FIGURE 9, the C, G and D triads sound special when accompanied by the open first (D), second (A) and sixth (D) strings. As notated, use your thumb to strum the triads—this keeps them physically distinct from the picked open strings. Once you can loop the two-bar passage smoothly, try developing our own p-i-m-a patterns.

FIGURE 9

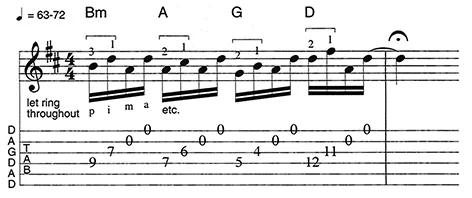

“You can fret major and minor triads on the fourth, fifth and third strings,” Simpson says. “And you don’t have to play all three strings. Can you see where these shapes come from?” He plays FIGURE 10A. “I’m thinking Bm, A, G and D, but I’m only playing the top two notes of each triad.”

FIGURE 10A

To visualize these intervals as part of a triad, refer to the brackets in this example. As you slide from position to position, keep the top strings ringing—these recurring fourths (A-D) supply a hypnotic drone.

“Now here’s where the tuning really opens up,” Simpson says. “In DADGAD, we have three D strings. Whatever happens on the fourth string can be fingered an octave lower on the sixth sting or an octave higher on the first sting—at the same fret.”

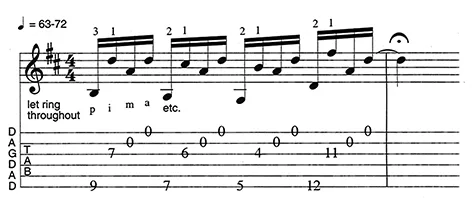

FIGURE 10B shows what happens when you play the previous example but drop the fourth string’s notes down an octave, to the sixth string.

FIGURE 10B

FIGURE 10C moves these tones up an octave, to the first string.

FIGURE 10C

“Now you have several news ways to play along the fretboard in DADGAD,” Simpson says. “Simply find your triads, and then experiment with moving the middle note to one of the outside strings. Imagine the possibilities!

“Also, we have two A strings in DADGAD, so we can shift the bottom voice of any triad up an octave. Just move the note from the fifth to the second string.”

To get a feel for this, first play FIGURE 11A, which features an ascending chromatic line on the fifth string. Now play FIGURE 11B, an extrapolation of this line. Notice how the notes on the fifth string are doubled an octave higher on the second string.

FIGURE 11A

FIGURE 11B

Take the time to create your own moves on the fifth, fourth and third strings, and then shift one or two voices to a different octave. Be patient. Sooner or later, the sonic and visual logic will reveal itself.

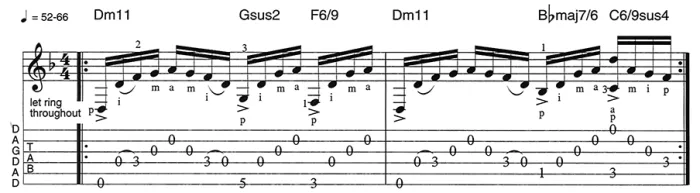

MINOR MATTERS

So far, we’ve explored DADGAD in a major context. FIGURE 12 illustrates how DADGAD can work equally well for minor riffs and progressions. As you play this D minor riff—keep it slow and steady—notice how the tuning lets you create lush harmony using only one finger. In this two-bar phrase, we cruise through Dmin11, Gsus2, F6/9, Bbmaj7/6 and C6/9sus4 with minimal fret-hand movement. The action is in the flowing picking-hand patterns.

FIGURE 12

Though DADGAD excels as an impressionistic folky tuning, Simpson proves it’s also potent for blues.

“I play [Howlin’ Wolf’s Willie Dixon–penned] ‘Spoonful’ in DADGAD,” he says, picking FIGURE 13’s syncopated riff. “Unless you hit the third string, it’s the same as open-D tuning.”

FIGURE 13

FINAL POINTERS

Be sure to try DADGAD with a capo. “It sounds wonderful at the 7th fret,” says Simpson,”in the register of a high-tuned five-string banjo.”

He also offers this advice for arranging songs in DADGAD:

“Usually I start with the bare melody. If you incorporate open strings, single-note runs can sound chordal, even through they’re not. Then I look for harmony. When I find it, I’m so happy. I work melodies into intervals and then intervals into chords. I get where I want to be through the sheer joy of examining all the internal mechanics. It can take years to really learn a tune, but I like to let the music prepare itself. It’s a different form of discipline.”