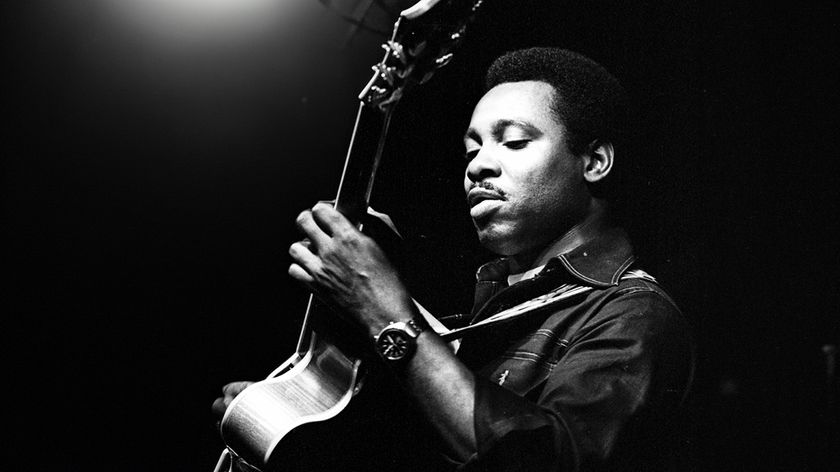

Country Jazz Lesson: John Scofield’s Cover of "Mama Tried" Part 1

Scofield’s instrumental is a harmonically sophisticated reinvention of a country classic, and a lesson in using jazz vocabulary in non-jazz contexts.

In this lesson, we’ll examine John Scofield’s instrumental cover of “Mama Tried,” a tune written by country music legend Merle Haggard. This song can be found on Scofield’s 2016 Grammy Award–winning album Country for Old Men, a disc that features a collection of country classics performed in a jazz style.

The main goal in this lesson is twofold. First, we will check out Scofield’s interpretation of the melody and examine how he uses specific devices to sculpt a variation on the original. Second, we will investigate how he uses jazz vocabulary to imply sophisticated harmony over the basic chord progression in the solo.

The lesson will be divided into two parts, and in this issue we will begin with a discussion on the melody and form.

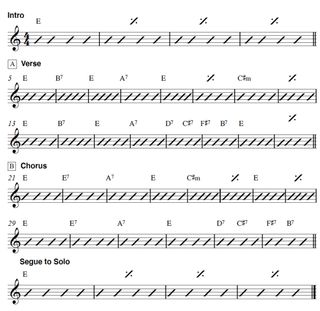

According to Scofield, this arrangement is played in the key of Eb, and his guitar is tuned to standard tuning, with a capo at the 1st fret. For purposes of this lesson, I decided to tune my guitar down a half step to Eb standard (low to high: Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Bb, Eb), dispense with the capo, and transcribe the song in the key of E, in order to make the chords and the key more familiar.

For reference, the original version by Merle Haggard is in the key of D. Example 1 illustrates the tune’s overall form, which begins with a four-bar intro followed by a 16-bar verse.

Unlike Haggard’s original song, this verse does not repeat and is played only once before moving on to the chorus, which is also slightly different from the original in that it has been reduced to 14 bars from 16.

The missing two bars overlap the Segue to Solo Riff, which is the four-bar section that’s similar to the intro and leads into the solo.

Now that we have an idea of the overall form, let’s examine each section individually, beginning with the intro, shown in Example 2 (0:00–0:04) Haggard’s original version of the intro is longer and features a second guitar part that plays a “train”-type rhythm behind the main idea.

Scofield takes his cue from the original but edits the riff to a four-bar phrase with a completely different melody and no additional rhythm guitar. This example is in the key of E major and combines single-note lines with double-stops and slides to create a hybrid “jazz chicken-pickin” type of sound.

Recall that Scofield’s recorded version is in standard tuning with a capo at the 1st fret. Since we’ve tuned down a half step in order to approach this tune as if it were in E, this intro lick will need to be performed a little differently, in order to accommodate the available open-string note options.

Notice how Scofield subtly implies an E7#9 tonality by adding a G natural on beat 2 of bars 1–3 over the E major chord. This figure will likely require a bit of slow practice before you’re able to ramp it up to the tempo heard on the recording. Make sure all of the notes are timed correctly and ring clearly.

After the intro, we have the melody (0:04–0:22), beginning with the verse at bar 5 (see Example 3). In many ways, Scofield’s interpretation of the verse is not at all like Haggard’s original vocal melody, but anyone familiar with it will likely hear how it is still present in spirit.

In addition to using a slightly different chord progression, Scofield creates a phrasing variation on the original verse by altering the rhythms and adding chord comping around the single-note melody line.

In the original version, the phrases in the verse all begin with a pickup into beat 1. By setting up the “1” and placing emphasis on the downbeats, a “straight” time feel is achieved. In contrast, Scofield’s reading of the melody favors phrases that start on beat 2.

For example, take a look at bars 5, 7, 9, 13, 15,17, and 18, which all emphasize beat 2 as the starting point for each phrase. By beginning phrases on beat 2, he gives the rhythm a “push,” or “lift,” which accentuates a swing-type feel.

As the verse unfolds, Scofield builds intensity by gradually adding counter-melodies and “echo” figures. For example, take a look at bars 5–12 and notice how he creates a countermelody line that “answers” the melody in a “call-and-response” fashion. This kind of conversational phrasing is commonly found in big-band arrangements, where melody lines are often “answered” by background horn-section parts.

Notice how all of these background lines are made up of the notes that are foundational to the underlying chords and that none of them contain any added extensions.

In bars 13–20, Scofield begins harmonizing the top voice of the melody in 6th and 3rd intervals and introduces a few three-note chords. By gradually thickening the texture of the melody line from single notes to three-note harmonies, he effectively builds intensity and momentum in the tune.

Even as things become more involved harmonically, Scofield manages to keep everything in one key by sticking to diatonic note choices, with no altered extensions in the harmony.

Now let’s take a look at Example 4 (0:22–0:38) and see how Scofield presents the chorus section of the melody that follows. Here, we notice how the idea of starting phrases on beat 2 is abandoned in favor of a more straightforward rhythmic approach that is closer to the original tune.

Also notice that there is more harmonic activity in the chorus than there was in the verse, particularly with the addition of three-note chord voicings in bars 21–24, and in bars 29–32. Again, these voicings are all made up of foundational chord tones, with no altered extensions.

A few, however, contain close intervals of a 2nd (the distance of a half step or whole step) which create tension within the chord, and also present some demanding fret spreads and finger stretches. After the chorus, we return to a slight variation on the intro figure (0:38–0:42), which I call the Segue to Solo Riff, since it functions as a buffer between the chorus and upcoming solo section (see Example 5).

Observe that this is where the chorus ends up being 14 bars long instead of the original 16, since the Segue to Solo Riff intersects it two bars early. You can still hear the chorus as 16 bars, however, since the first two bars of the connecting riff remain on the E chord, it makes more sense to think of this as a 14-bar chorus followed by a four-bar riff.

Now that we’ve examined some of the details of Scofield's crafty interpretation of the tune’s melody, see if you can learn it in its entirety by working on one section at a time and putting everything together. Have a listen to both the original and the Scofield version for inspiration, as well as for reference and context.

We also recommend recording or looping the chord progression to the verse in Example 1 and using it for a backing track, as that will effectively provide some harmonic context for the melody.

In Part 2 of this lesson, we’ll continue our analysis with an in-depth look at Scofield’s solo on this tune and investigate some of the techniques he used to craft hip jazz lines over the simple country chord changes.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band

"This is something you could actually improvise with!" Add vibrant rhythms and sophisticated chords to your guitar playing with Jesse Cook’s five essential flamenco techniques