Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Albums and Artists that Made 1971 Guitar’s Greatest Year

The spirit of ’71 is well and truly alive in this historical lesson.

In 1971, rock and roll guitar was barely in its teens. But, remarkably, what started as R&B- and western-swing-infused three-chord rave-ups had grown to incorporate elements of folk, Chicago blues, modal jazz, Indian classical music and flamenco. The music of the 1960s – especially that of the Beatles – proved that the pop charts could deliver expressive, high-quality artistry that rivaled that produced in jazz clubs and symphonic halls. The music of the time also became the de facto voice of one of the most significant cultural upheavals in American history.

As the new decade dawned, musicians were presented with a blank canvas on which they created what can rightfully be seen as the rock era’s belle époch. Indeed, many famous artists released their defining masterpieces during this fertile 12-month period.

Guitar Player has celebrated the 50th anniversary of this magic year with features on some of the greatest albums from 1971. Now, with it just about over, let’s have one final celebration of the albums, artists and guitarists that made the year so significant.

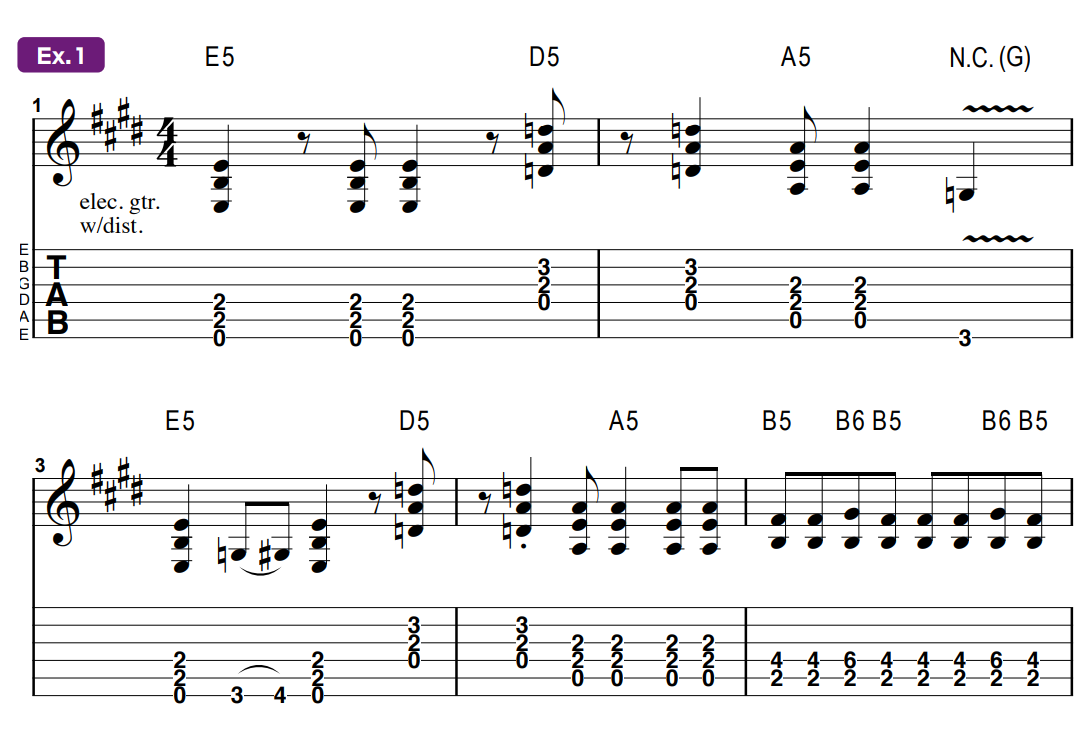

Power (Chords) to the People

The Who’s 1969 rock opera Tommy was an ambitious project that established them as major players, but it was 1971’s Who’s Next that is often considered their crowning achievement.

Ex. 1 is loosely based on the pugilistic power chords Pete Townshend delivers during epic anthems like “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again.” The consummate rock rhythm player, Townshend didn’t merely “strum.” Rather, he attacked his strings with powerful percussive jabs, pioneering a style that would evolve into punk and metal in the hands of the next generation. When playing this example, try using a short, controlled wrist motion, striking the lowest strings with extra oompf!

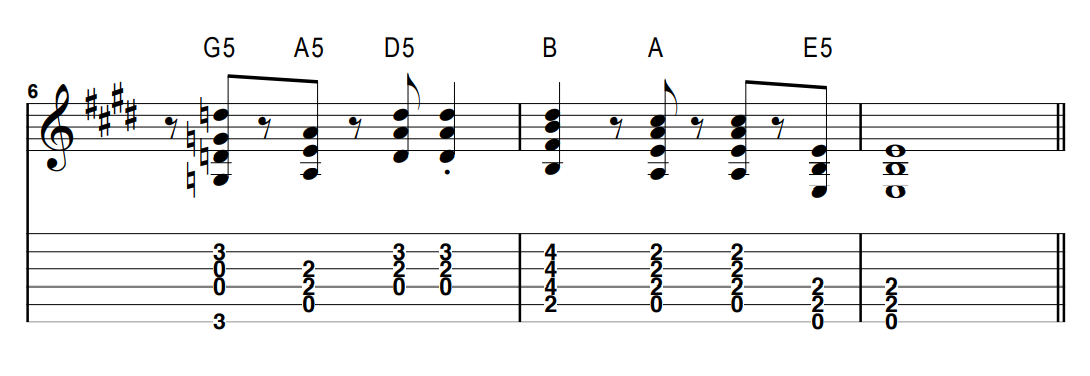

Going for Soul

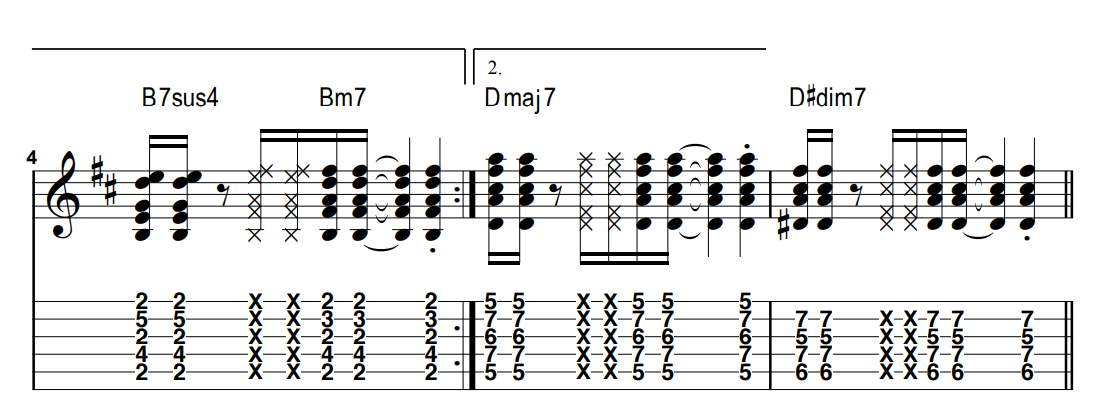

A 2020 Rolling Stone poll cited Marvin Gaye’s 1971 release What’s Going On as the greatest album of all time, and though polls are subjective and art isn’t easily quantifiable, the album’s merit is unquestionable. Gaye’s emotive vocals and heartfelt lyrics are front and center on this song cycle about a Vietnam vet returning home to find his country in turmoil. However, the unsung heroes of this and many other great Motown releases are the Funk Brothers, a loose collection of studio musicians who played uncredited on dozens of hits.

Ex. 2 recalls guitarist Robert White’s pulsating chord work on the title track, a clever combination of jazz harmony and funk rhythm. To play the percussive “scratch” strums (indicated by Xs), simply loosen your fret-hand’s grip on the neck without taking your fingers off the strings. This will effectively mute the strings, so that, when strummed, they produce the hollow, pitchless “chick” sound that is a signature of funk guitar.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

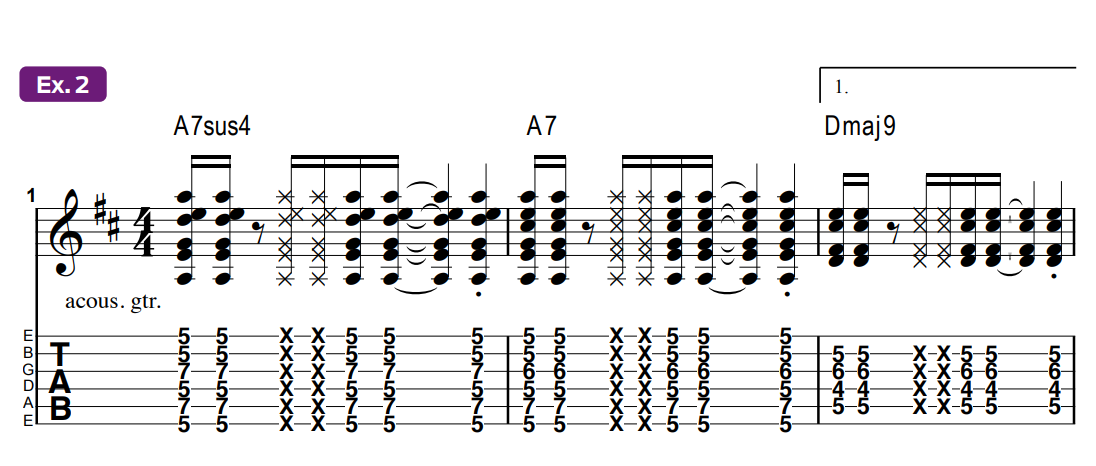

Sticking It to the '70s

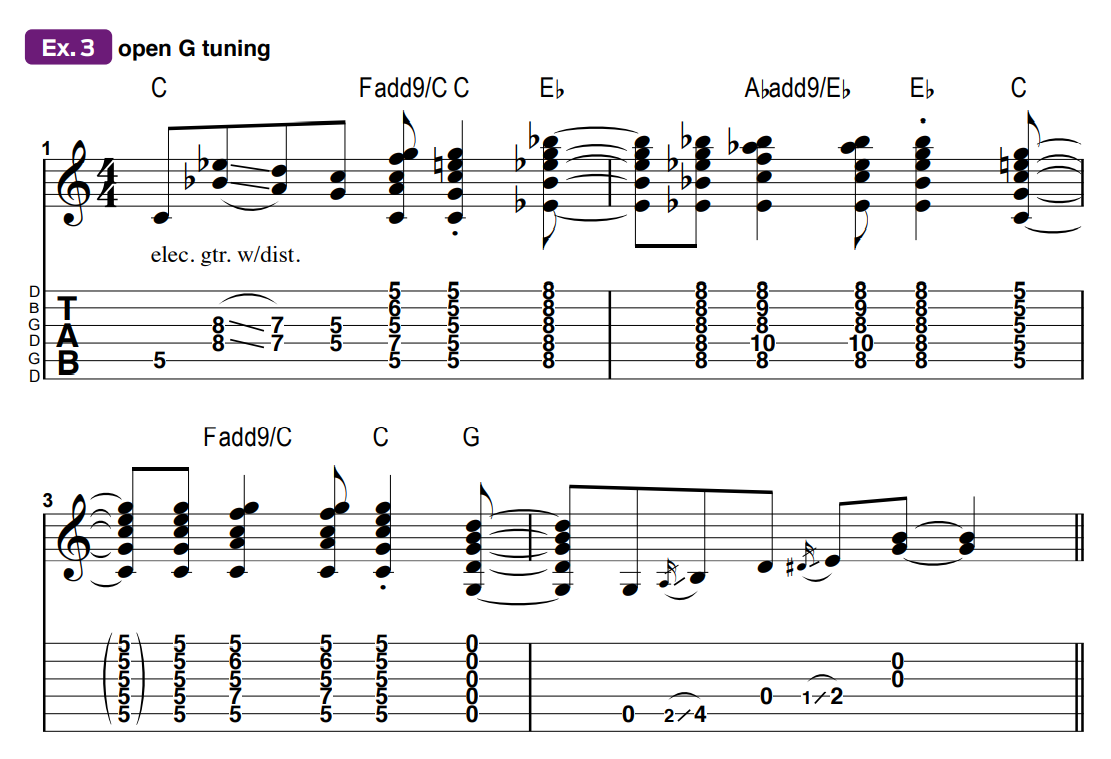

The Rolling Stones were indisputably one of the most popular and influential musical acts of the ’60s. As the decade drew to a close, however, dark clouds seemed to be forming on the horizon. The band experienced the death of founding member Brian Jones and watched in horror as the Hells Angels security detail they hired for a 1969 concert at Altamont Speedway murdered one attendee and brutalized several others.

They also sought to extricate themselves from management and recording contracts. Come 1971, the band returned with their own label, a new iconic tongue-and-lips logo, and arguably their finest record to date, Sticky Fingers.

Around this time, Keith Richards had fully embraced open-G tuning (low to high: D, G, D, G, B, D), and Ex. 3 takes inspiration from his clever riffage and chord voicings on such Stones classics as “Brown Sugar” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking.”

Meeting of the Masters

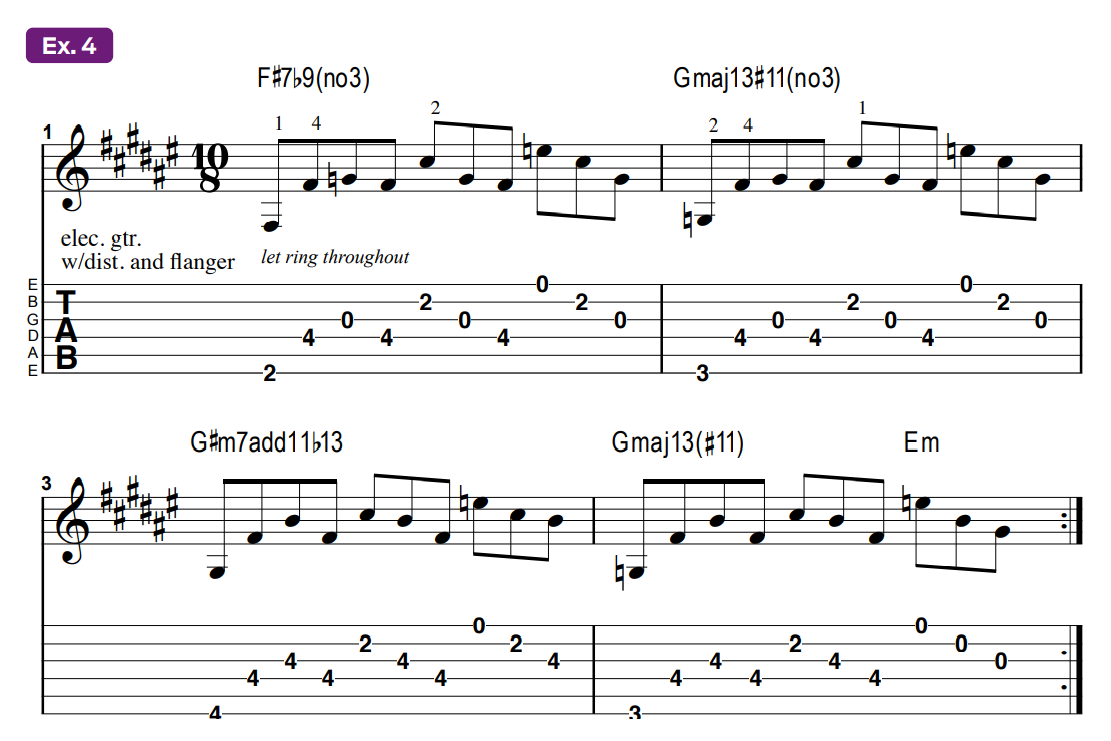

Miles Davis was a pioneer of multiple styles of jazz, including bebop, cool, hard-bop, and modal jazz, and when he incorporated electronic instruments and rock beats on 1969’s Bitches Brew, jazz-rock fusion was born.

Two years later, former Davis guitarist John McLaughlin formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra, a quintet that blended jazz harmony and improvisation, Indian classical scales and rock instrumentation into an incendiary mix. Their 1971 debut, The Inner Mounting Flame, was a hit with rock audiences and established them as the premier fusion band of their time.

Ex. 4 is modeled after “Meeting of the Spirits,” a track that begins with McLaughlin’s hauntingly exotic arpeggiated chords before exploding into an impassioned exploration around the Phrygian-dominant mode (1, b2, 3, 4, 5, 6, b7).

Tapping Into English Moods

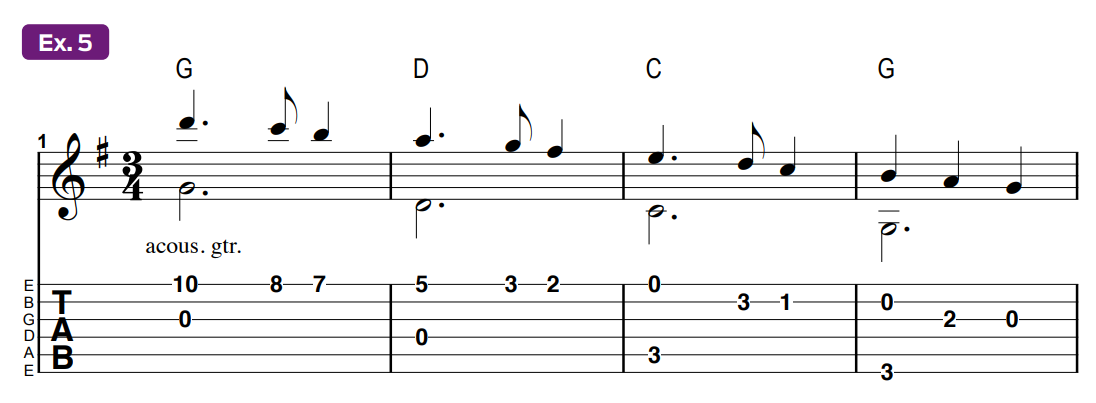

Without a doubt, 1971 was a landmark year for progressive rock, a style of music that drew heavily on European classical influences.

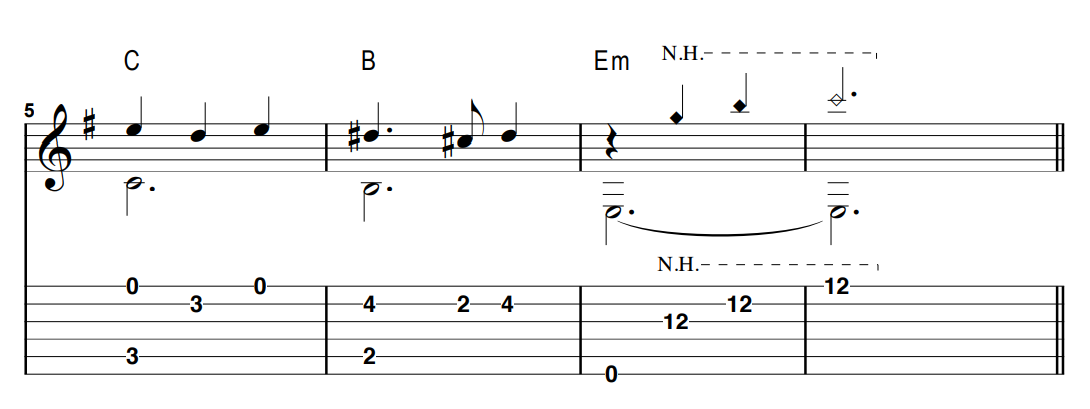

Ex. 5 is an homage to guitarist Steve Howe’s use of classical guitar techniques to enliven songs such as “Roundabout” and the solo piece “Mood for a Day” that were featured on Yes’s brilliant album Fragile.

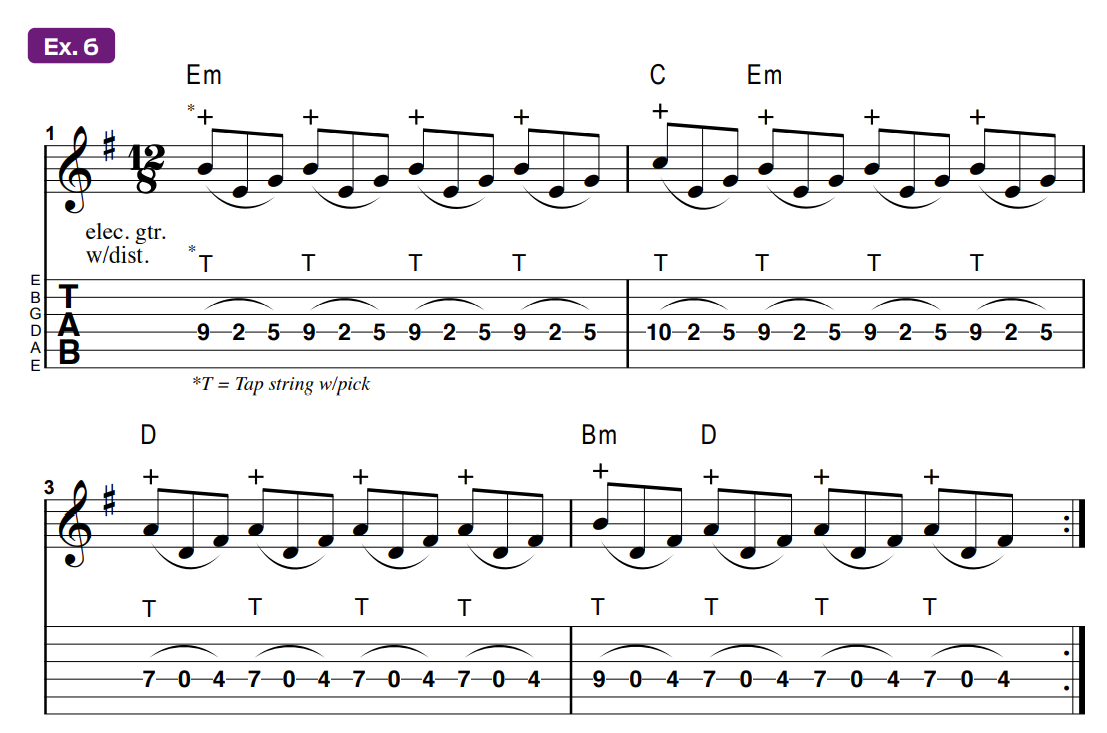

Another significant prog release from 1971 was Genesis’s Nursery Cryme. Although not as well-known as Fragile, the record did herald the debut of Steve Hackett, a guitarist who employed fretboard tapping several years before Eddie Van Halen.

Ex. 6 recalls his approach on “Return of the Giant Hogweed,” but unlike Van Halen, Hackett would tap the strings with the edge of his pick instead of using a fingertip.

A Case of the Blues

Although often labeled as a folk artist, Joni Mitchell drew inspiration from many sources. Throughout her storied career, the eclectic composer has melded elements of jazz, pop, blues, and electronica in with her songwriting and has collaborated with artists as varied as David Crosby, Charles Mingus and Pat Metheny.

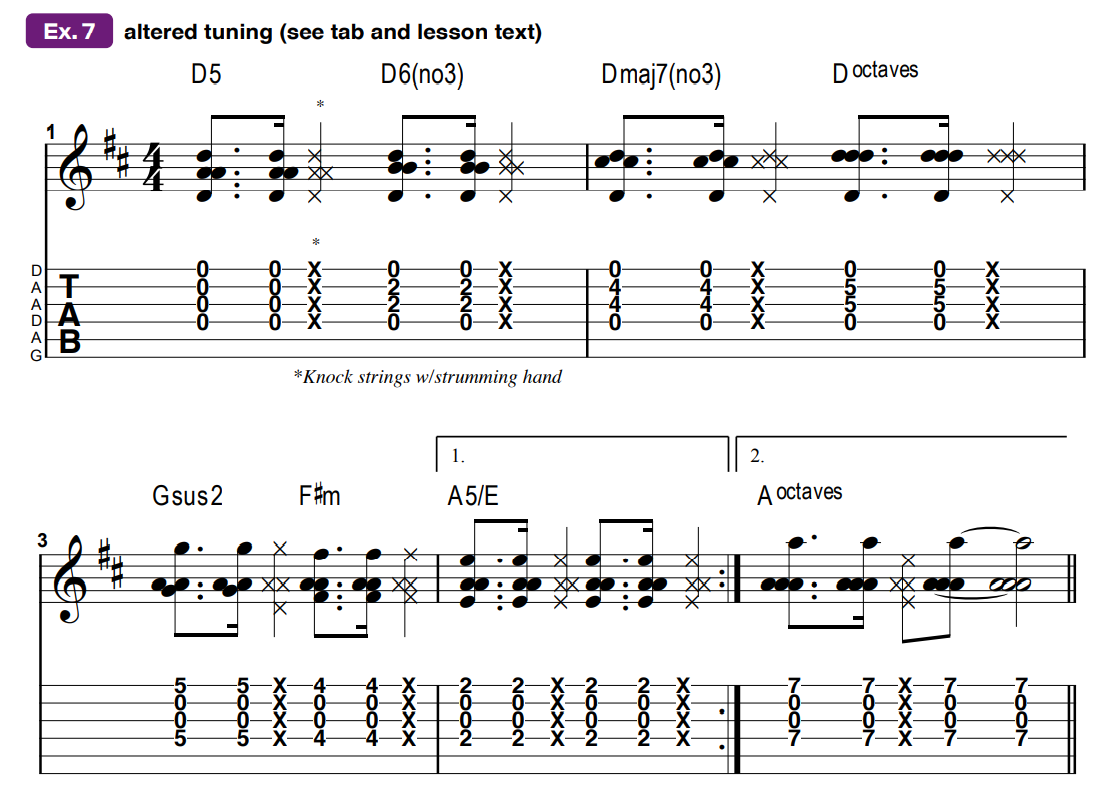

Mitchell often wrote and performed in a wide variety of open tunings, many of her own design, but for 1971’s Blue, her instrument of choice was often a four-string Appalachian dulcimer.

Because of variances in string thickness, it’s impossible to match the dulcimer’s tuning and timbre on a standard guitar, but for Ex. 7’s approximation of “A Case of You,” we tuned the top two strings down a whole step, to A and D, respectively, and the G string up a whole step to A, resulting in two unison A strings. This makes our tuning, low to high, E, A, D, A, A D.

If you stick to the top four strings, it evokes the droning unisons, octaves and 5ths associated with dulcimer tunings. Perhaps the larger lesson here is inspirational and not technical. Mitchell’s fearless artistic exploration and constant experimentation is a beautiful reminder to step outside of our comfort zones.

My Back Pages

As 1971 dawned, Led Zeppelin – the supergroup that Jimmy Page had formed in the wake of the Yardbirds’ dissolution – was already in full flight, but it was their fourth album (generally referred to as Led Zeppelin IV, but officially named by the four cryptic symbols that adorned a sticker on the album’s wrapper) that would cement their legacy as the greatest hard rock band of all time.

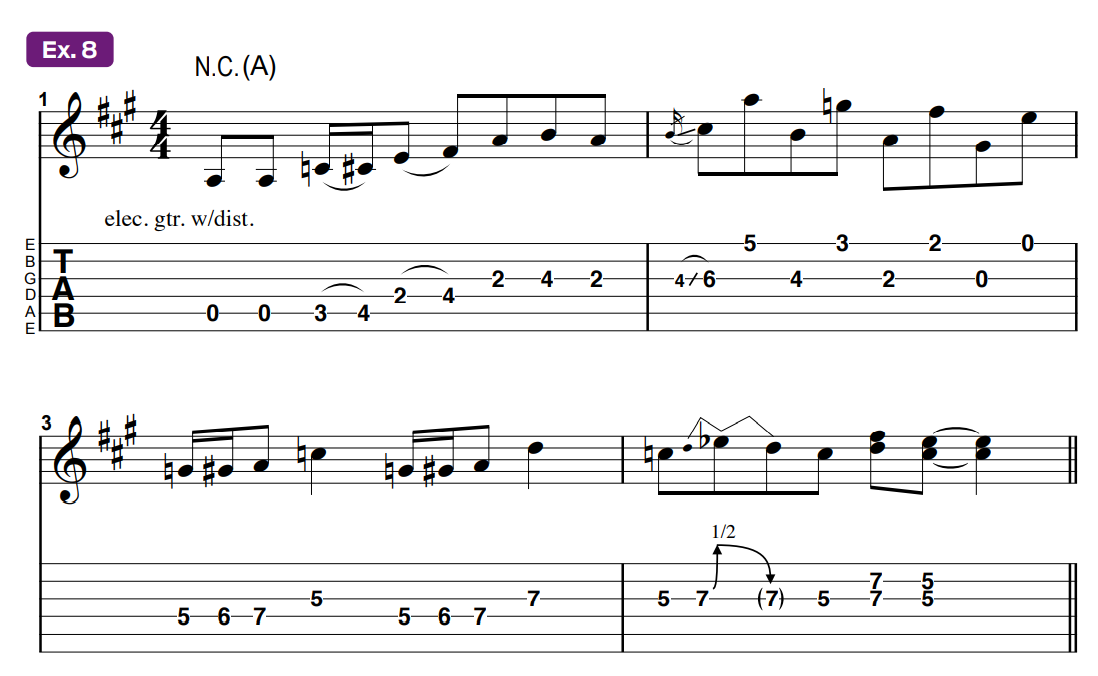

Ex. 8 is inspired by the outro to “Black Dog” and demonstrates Page’s clever appropriation of country and blues licks to extend rock’s lead vocabulary beyond simple pentatonic scales. Centered on an A dominant-7 tonality, it makes effective use of b3, b5, and b7 color tones (the C, Eb, and G notes, respectively).

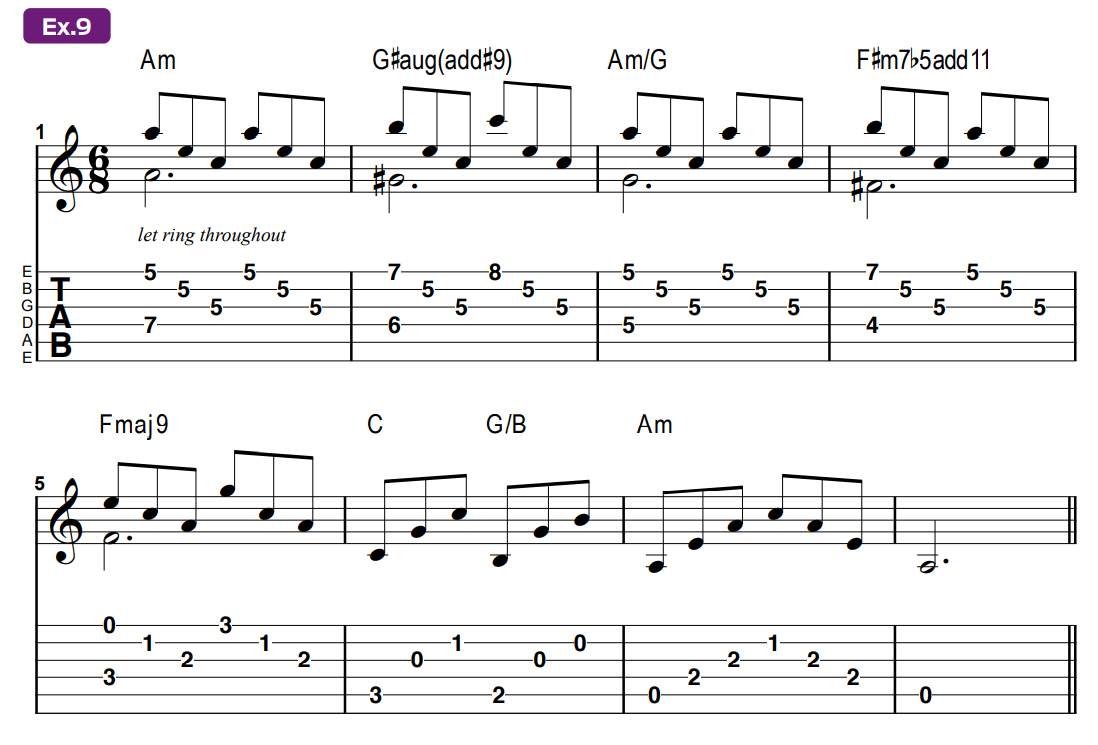

For our final example, we’ve chosen to template what is perhaps the most culturally iconic and controversial guitar lick from 1971; Page’s intro to “Stairway to Heaven.” Recent lawsuits have pointed out a similarity to Spirit’s 1969 track “Taurus,” but to our ears, both songs are based on a common musical trope – an A minor chord arpeggio with a bass note that descends down in half steps. Its use in rock music predates Spirit (Google: Ace of Cups “Simplicity” 1968). And, like a 12-bar blues shuffle, it’s arguably fair game when songwriting.

What makes Page’s take on this cliché stand out is his incorporation of contrary motion between the outer voices, with ascending notes on top pitted against descending bass notes. This is a cleverly appealing compositional move, which we’ve also used for Ex. 9.

Although we’ve covered several albums with an enduring legacy, we’ve barely scratched the surface of the major releases that turned 50 this past year. David Bowie’s Hunky Dory, the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East, Jethro Tull’s Aqualung, Pink Floyd’s Meddle, the Doors’ L.A. Woman, Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain, Black Sabbath’s Masters of Reality, Elton John’s Madman Across the Water, Janis Joplin’s Pearl, John Lennon’s Imagine, Van Morrison’s Tupelo Honey, George Harrison’s The Concert for Bangladesh, Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story, and Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On are among the many great albums making a compelling case that 1971 was in fact the guitar’s – and modern music’s – greatest year.