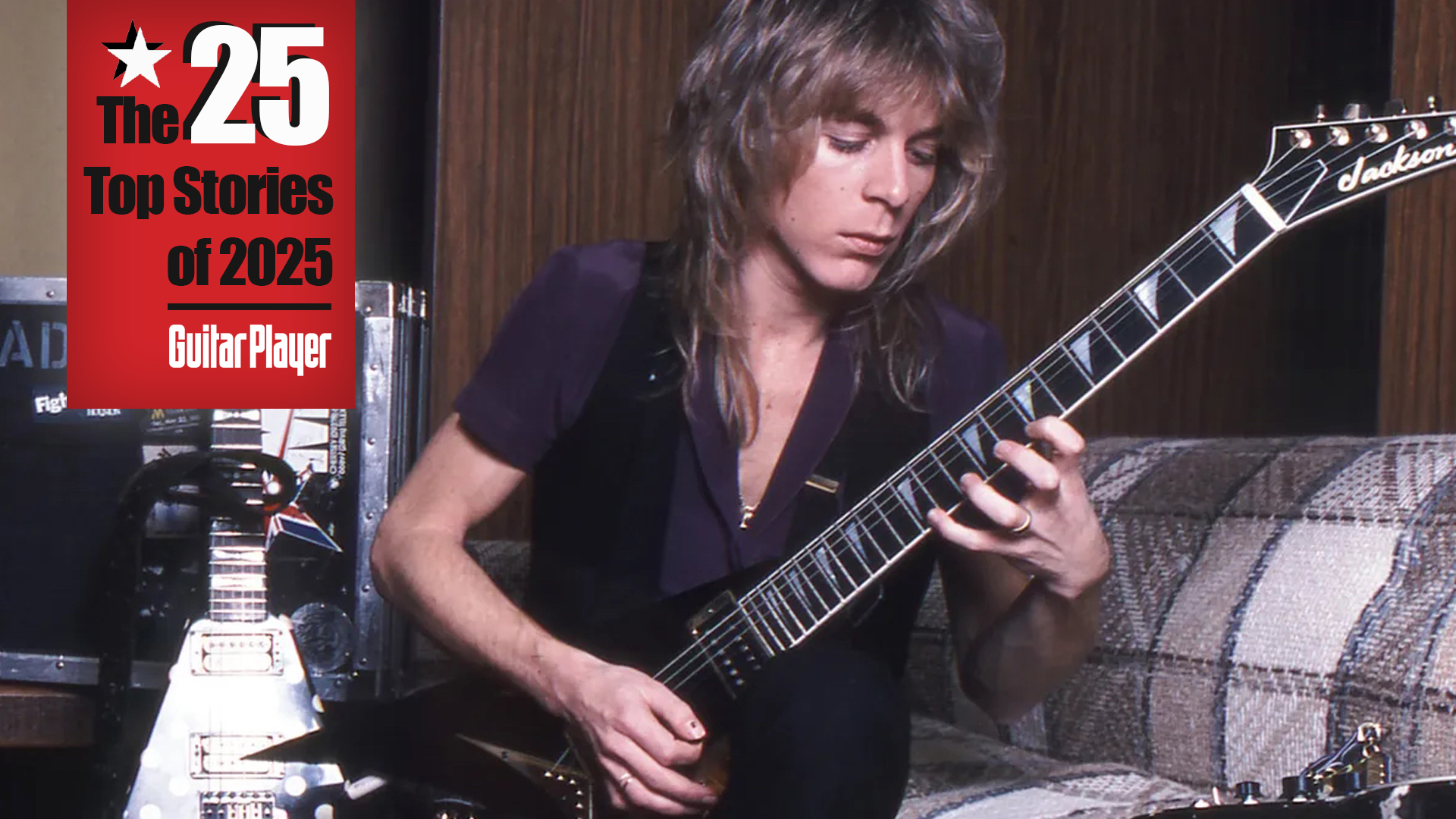

“When I play a solo, the best score I can get is 75 percent. I got to a point where I accepted that.” Steve Morse on how to keep your cool when the going gets tough

Now 50 years into his career, the 70-year-old guitarist shares the lessons that have kept him growing in his art

In a recent interview with Guitar Player, while discussing the 10 albums that changed his life, Joe Bonamassa had kind words for Steve Morse. “I really hold Steve Morse in such high regard,” he said.

“Not only as a player but as a good, humble guy. Unfortunately, he doesn’t get named in the same sentences as a lot of other players of that era, like Eddie Van Halen, Allan Holdsworth and Bill Nelson. He’s the last to be named or not named at all.”

Turns out that Joe B. was right. As Morse himself checked in with GP, his affable personality and endless humility were apparent from the hump. After some 50 years making music, the 70-year-old guitarist remains unpretentious and clear-eyed about the art of playing guitar.

“It’s a never-ending struggle,” Morse admits. “But when you look at anything worth doing, there’s always going to be struggles.”

“It’s like a NASCAR race,” he continues. “There are guys on the pit crew struggling to keep things reliable, but everything is always deteriorating. As a musician, my skills and technique will deteriorate, so I always have to replenish them. It’s a constant struggle; it’s never going to change.”

It’s not all bad, of course, and Morse still loves the game. “The joy of creating music and playing music is a constant,” he beams. “It’s always great. It’s like, ‘Okay, we had a terrible gig,’ but you can have a great gig under the same conditions. It’s about fighting for it and finding balance.

“I started off as an annoying teenager with an electric guitar,” he laughs. “I slowly transformed to the place I’m at now, where I’m humbled and impressed by anybody willing to work hard and play a great solo,”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Starting with your Dixie Dregs days, what were the biggest challenges you faced while on the road, and how did you overcome them?

In the early days, the sound systems weren’t that good. Some places just had a P.A. for a vocalist, and we didn’t have one. So these places wouldn’t have enough inputs and headroom to mic everything. We got this idea to have everybody play through two sound sources — basically, two cabinets. We had two Leslies, two bass cabinets and two guitar cabinets, which, for the most part, allowed us to play shows without monitors.

Did you find that to be reliable?

The only reason that fell apart was that it was similar to the mutually assured destruction of nuclear power that was written about in the ‘60s, where everybody had the ability to destroy the world. And that was supposed to deter things because that meant that if anybody acted up, they’d get blown up.

With our equipment wars, all it took was one person playing a little bit too loud for another band member on the other side of the stage to turn up their equipment. The person that turned up loud to begin with would hear more of that instrument on their side of the stage, so they’d turn up again. That made us revert to a traditional band setup and letting everyone be the loudest thing.

Was there a specific turning point for you regarding your personal equipment on the road?

When I came across the idea of muting the output of the speakers. That was before there were power attenuators that went between the speaker and the amp. I tried running higher impedance on the speakers by putting them in series, and I employed a cover for the speakers — basically, anything thick that I could cover the speakers with. By doing that, I could turn the amp up enough to get the tube saturation I was looking for.

Once you joined Kansas, how did your challenges on the road change?

With Kansas, we had a team, including roadies, so my interaction with my equipment was about finding a place and a volume for me to fit in. At the time, the vocals were loud through the side fills, and that’s when I started using earplugs for every show because I was next to that side.

This is around the time you started using Engl equipment, right?

Yes. I started using Engl front cabinets and putting them on their side so the two 12s would be pointed in one direction. The other two 12s would be pointed in a slightly different direction, rather than being pointed up at my head. That gave me a little bit more headroom, and I could hear myself without the monitors.

A lot of players are fine with sound through the monitors. Why was that an issue for you?

For some reason, to me, when I hear a guitar through monitors, it sounds like it has a little bit too much presence. Unless I hear the whole band through the monitors, it seems like the guitar doesn’t fit in sonically. So I try to limit the monitors as much as possible so that I get more ambient sound.

In those early days, was there ever a time when you felt like you failed onstage?

Yeah. Those times are what I referred to as “normal shows.” [laughs] Music has always been challenging enough that, at some point in the show, you miss something that you know you can play.

How do you overcome that?

You just have to keep going. The good thing about playing music day in and day out is it keeps you very humble. I got to a point where I just accepted the fact that when I play a solo, the best score I can get is 75 precent. Well, that’s the best average performance; I can play a horrible solo, and sometimes I play a great solo. But the average of that is 75 percent.

Has that ever impacted your ability to enjoy yourself onstage?

It’s still fun for me. If you’re enjoying yourself onstage, that sense of excitement, — and in a small way some risk taking — conveys something to the audience. To this day, when I play a show, there’s a point where I screw up, and I just work around it and immediately fix it. I’ll hit a wrong note or mess up a chord change, and I’ll take those wrong notes, bend it in one or two ways, and it’ll fit.

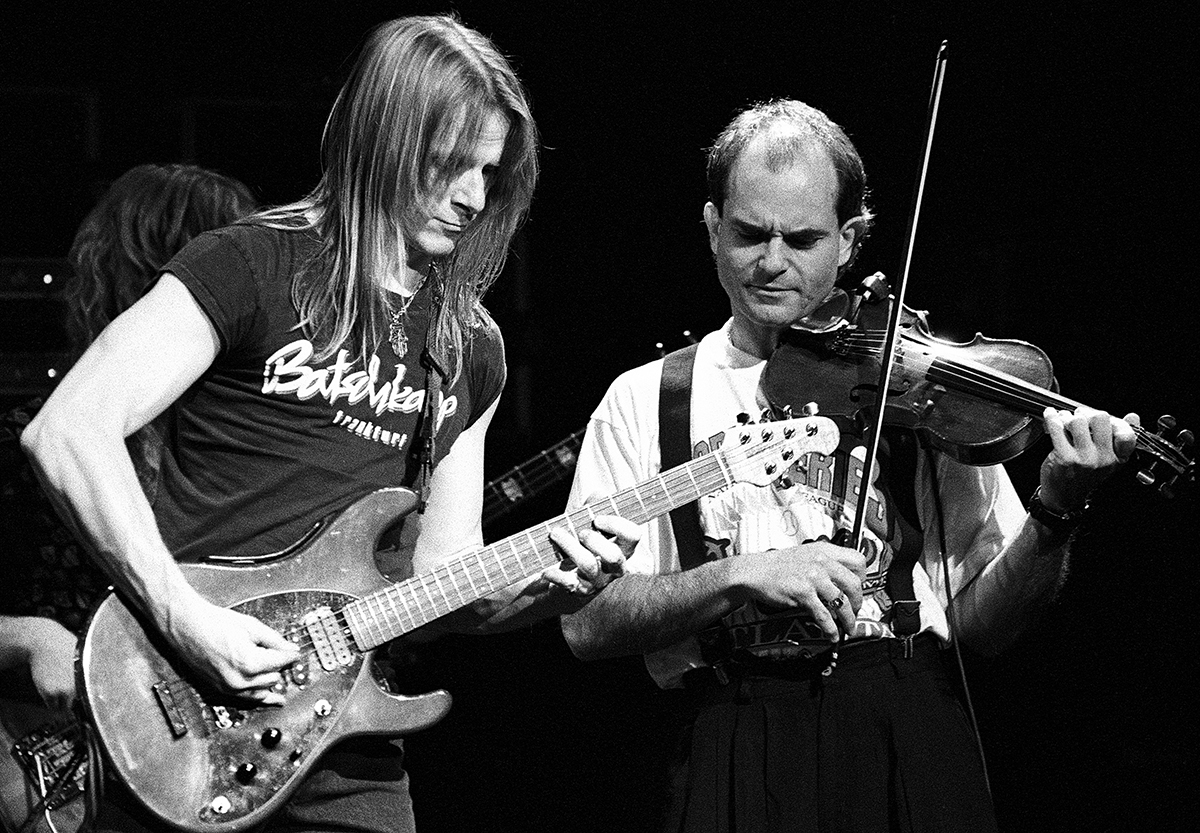

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced shifting from Kansas to Deep Purple?

My first encounter with Deep Purple was a really good jam session, and my first encounter with Kansas was a writing session. Those were different things, but they were the things that I connected on with each band. With Kansas, it was more about writing, but with Purple, it was about the feel of everybody improvising, listening and reading each other’s minds. With Purple, that connection grew very organically.

Did you need a whole new setup to cover Ritchie Blackmore’s parts?

I eventually changed the amplifiers four times before I ended up going with Engl. When I first started with Purple, I was using a 5150 setup. I used that through the [1996] Purpendicular album. That setup worked fine, but the gear needed to be turned up in order for the type of distortion I needed to convey the notes. The search began to find a rounder tone with more impact. That led me to the Marshall Jubilee to the Marshall 2000 series to Engl.

What made Engl Amps perfect for Deep Purple?

At the time, I liked some of the characteristics, but I really wanted to make some changes. Luckily, the designer started bringing prototypes to the shows with breakout boards attached to the amps that let me adjust the tone centers of the tone controls. It was awesome. That begat my signature amp.

What’s the most significant stumbling block for any guitar player trying to survive in a rock band on the road?

Oh, boy. To ensure success within a band, you have to give respect. If the lobby call is at 10 a.m., you need to be there at 10 a.m. the latest, and be prepared. You better learn your parts and really learn the arrangements before soundcheck so you can work on sound changes and figure out what pickups you’ll use and whatever else.

When you’re in a band, you’re on a team, just like a football player. It takes a whole team to do well before you’re going to be a great band. Every minute of your life needs to be spent becoming a better player. It goes back to basics; if you have a road crew, treat them with respect, help them when you can, and realize they’re just like you; they’re just doing a different job.

What challenges do you face today on the road, and how do they differ from your early days?

The equipment is just better and more reliable. And with digital tuners, things are better right off the bat. Usually, you have fewer excuses for screwing up. [laughs] Things are easier, I think, than they’ve ever been on the equipment front.

So what’s not easier?

What’s not easier is getting the gig experience that we got back in the ’60s and ’70s. I always want to support anybody who’s doing live music because we need to keep that alive, to give young people a chance to develop their craft. Nothing can take the place of live performances for honing your art. Nothing can be as exciting as a live performance from a listening standpoint.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.